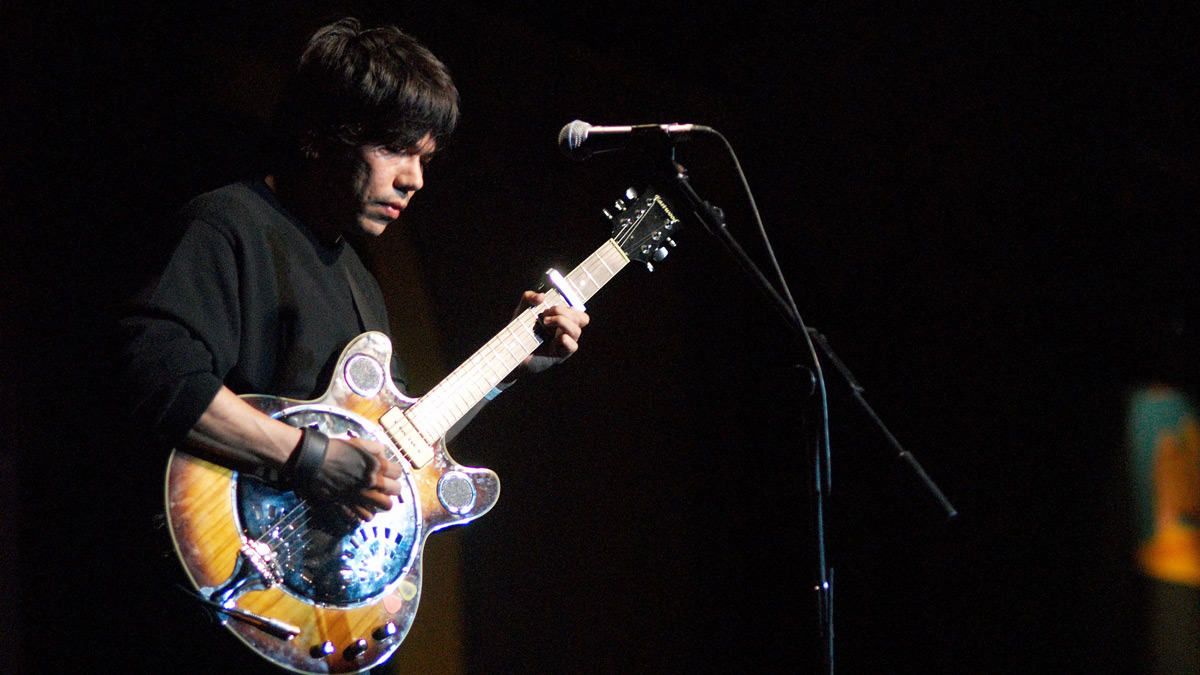

David Pajo’s top 5 tips for guitarists: “You don’t have to know music theory to convey an emotion”

Trailblazing Slint and Papa M guitarist on how making your own scales and finding your own sound will change you as a player

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As David Pajo tells it, six hours of practice for his teenage self was never enough. He needed nine, and he let his mother know all about it. We can relate.

At 16, he dropped out of high school to play music all the time. He was a 24/7 player in those days, and listening to the sort of enthusiasm he has for the guitar, he seems to have changed little since.

His parents relented so long as he passed his GED and attended music school. But attending Berklee College of Music, in Boston, Massachusetts, helped both expand his musical vocabulary and focus his mind. As a teenage punk, Berklee was a little too staid, too safe - and those experiences changed him for good.

Article continues belowI really like Delta blues; to me, it was all these notes that probably shouldn’t work in this giant jumble

"I remember going to see Berklee graduates, and meeting other students, and all the graduates played exactly the same,” he remembers.

“They were all really good. They had this sort of jazzy style. But I thought, ‘I don’t wanna be morphed into that guy.’ Y’know, where I’m just playing coffee shops and showing off, and kind of not really expressing anything other than: ‘Look at me, like I can play this stuff and I know all these scales!’ So that’s when I decided that music theory wasn’t for me. I had to just go my own route.”

That route saw him play in Slint, a coltish post-rock, whatever-rock band operating out of Pajo’s home turf in Louisville, Kentucky. Their sound articulated perfectly both adolescence’s angst and hope, and the slack time that made our youth feel eternal despite it being anything but.

Through their 1989 debut, Tweez, recorded with Steve Albini, and their sophomore classic, Spiderland, Slint had a profound influence on the following two decades of alternative rock. Pajo was reminded of Slint’s philosophy to songwriting when working on reunion shows, and if reflects his on/off relationship with music theory.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“That was one thing with Slint that I was really into,” says Pajo, “I would talk about it with our drummer, Britt [Walford]. I really like Delta blues, because to me it was like a mixture of the blues scale, and harmonic minor and major scales, and it was all these notes that probably shouldn’t work in this giant jumble but they totally evoke this multi-dimensional thing, and I think that in Slint, we consciously tried clashing notes to see what happens and see if we can try work them into songs, like, ‘Let’s mix the happy scale with the sad scale and see what happens!’”

Pajo has since been involved in all kinds of projects. He has played with Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Will Oldham, Tortoise and more. His latest record, A Broke Moon Rises, a solo recording under the name Papa M, is an offbeat guitar concerto that Pajo says can exist happily in either the background of the foreground.

It’s a tour-de-force of acoustic arrangements, of deconstructed flamenco and bittersweet Americana. More than anything, it’s a lot of fun, just the sort of gentle virtuosity we have come to expect of Pajo. A Broke Moon Rises is far removed from Slint musically, but it was created with a very similar attitude.

As Pajo says, “After the Slint reunion I remembered that mindset, and I think it did affect this new record in a sense that there are moments where I tried to explore those ideas of clashing notes.”

As he dispenses his five tips for guitarist, "clashing notes" could be a theme. How better to some up his on/off relationship with music theory?

1. Don’t make learning theory your be all and end all

“I think music theory is overrated, and if you are destined to learn it you’ll figure it out yourself over a period of time, and if you want to go back and figure out the names of note relationships or whatever, you can do that.

You can be thinking too much about the theory of the notes and their relationships, and not about the emotion behind it

“You have lots of time to do that. Initially, when you are learning guitar, and when you are writing songs, music theory can actually be a cage, and you can be thinking too much about the theory of the notes and their relationships, and not about the emotion behind it.

“To me, you don’t have to know music theory to convey an emotion. There are lots of instances of this! A well-crafted song might be from someone who knows music theory inside and out and knows how to express themselves through those parameters, but I don’t necessarily think that it is as important as people say it is when you are starting out, and I can relate, and experience has confirmed that with me, because that was my suspicion when I was younger.

“I knew the blues scale, and I had someone write down a bunch of scales, like Phrygian, and all those different ones, and I would play them a little bit but I didn’t really care about the names of them, or I just knew that this scale kind feels exotic to me, or this one, the harmonic minor, is sad, and major is happy! That was all I needed to know.

“I think I do have a basic grasp, or a pretty good grasp, of music theory now, and it’s just because I know it from playing so much, and playing other people’s songs so much. Like, a lot of times I don’t know the names of things, but I understand it, y’know, I understand the relationship between the chords or the notes.

“So that’s my first one: don’t worry about music theory. You don’t have to know the name Mixolydian or Phrygian to know the gist of it, and that leads me to the second one.”

2. Practise soloing in different scales

“Regardless of whether you know the names or not, you can give them your own names. I don’t think the names are that important, but you should practise soloing in different scales, maybe ones that are not familiar to you, but they don’t have to be ones that are even taught to you.

“You can make up your own scales, or have your own tuning so you have to invent your own scales. The more you can mess with it, or try doing the wrong thing – shit! I just gave away the fifth one! – is better. So I guess it is good to practise, it is good to challenge yourself, but you could be practising stuff that you yourself have invented. It doesn’t have to be somebody else’s song or solo or whatever.

“[Being different] is what it’s all about; technically, I don’t think Thurston Moore is a great guitar player to be honest, but he is hugely influential on me and I totally love his guitar playing. Like, I never thought to put a drumstick under my strings. I never thought to detune a guitar to where I didn’t know what the tuning was and I couldn’t touch the tuning pegs if I wanted to play the song that I wrote on that guitar!

At a certain point, you should learn as much as you can about guitar, but I think unlearning it is also the way to go

“Like that kind of stuff is so anti-guitar in a way, and it kind of forces your brain to think. I don’t know if he’s still like this but I know that early on there were guitars that he could just not touch; he couldn’t change the tuning because he didn’t know what the tuning was, and, probably, a lot of it is micro-tonal in the sense that they’re not tuned to 440 pitch anyway. But it gave them their own sound that no-one could recreate.

“At a certain point, you should learn as much as you can about guitar, but I think unlearning it is also the way to go. I remember reading a lot time ago, from some guru, that you should spend seven years learning an art or a profession, and then for seven years you should not do that art or profession at all! [Laughs] And then, after that, that’s when you have the life experience behind it; you know have more life experience so when you come back to where it is it’s gonna be more powerful.

“That was something that always stuck with me, the idea of just unlearning something after a while. Like you learn the technique and the physicality of the guitar but then you kind of have to throw away everything that you’ve learned and look at it as a blank slate.”

3. Get yourself a bag of tricks

“There’s this blues guitarist in Louisville, this old guy from Louisville, Kentucky, where I was brought up. He’s this old blues guy, an albino black man called Smoketown Red, and he said that the best advice he could give to guitar players was to collect your bag of tricks, like the things you know are impressive or that work, throw them in the bag and then learn them enough so that when you need to bust them out they are there for you.

“Like if you play yourself into a hole you can pull out one of your bag of tricks to save you. And it really is a cool way of looking at guitar playing, because I do feel like I have a bag of tricks that I can use when I am desperate! [Laughs] Or like my girlfriend’s mom is like, ‘Oh, you’re a guitar player, play something!’ I can pull something out of my bag of tricks.

”So I guess there are different philosophies to it but have a bag of tricks at your disposal. A vocabulary is a good way of looking at it because you are finding your own musical language; you can take bits from others but you are basically making your own language up.”

4. Steal from the best and make it your own

“I don’t want to see an imitation Black Sabbath. I don’t want to see an imitation of Velvet Underground. People have already done it; they’ve already found their sound and expressed it, but if you are a clone of that it’s not very exciting – even if you beef up the production values or whatever! But if you can take from those bands and make it part of your own language, then you’ve done something really cool. You’ve taken something you like from those bands and made it your own.

“Like Sleep: to me, Holy Mountain, when I first heard that I thought, ‘Wow, these guys are Black Sabbath!’ But then they took it to a different level and I think they created their own sound out of that imitation that they started off with. Now, Sleep sounds like Sleep and Black Sabbath still sounds like Black Sabbath. You can hear that one references the other but has made up their own sound.

There’s nothing wrong with copying somebody’s vibe but you have to make it your own. If you are just an imitation then you are gonna be forgotten

“It’s the same with Mogwai. Like they may have started off with some Slint influence but I knew from the start that they were making it their own, and now there’s a Mogwai sound that’s not a Slint sound. They have their own sound. That’s what good music is supposed to do; you are supposed to steal from other artists. That’s how music evolves. There’s nothing wrong with copying somebody’s vibe but you have to make it your own. If you are just an imitation then you are gonna be forgotten.

“All the Elvis Presley clones aren’t memorable. They were just following a fashion. But he was taking from black artists; that was really shocking at the time, for a white guy to be singing like a black artist was really shocking - but, again, he made it his own and now we know him as Elvis. It’s the Elvis sound. But it’s not like he wasn’t stealing. You don’t want to make it so obvious.

“I would laugh at bands when you could hear their influences so obviously, but if you can take bits and pieces from another band and make your own soup out of it, that is what’s going to change people’s minds and get people’s attention.”

5. It’s important to do the wrong thing now and again

“Like what I was saying about clashing notes, just try it. You know you are not supposed to do that so you should probably do it. Maybe don’t apply that in life, in other ways! But with guitar, you’re not gonna hurt anybody, you’re not gonna hurt yourself, so just jump in there and try it out.

A melody can be beautiful, it can be dissonant; it can be beautiful in its dissonance, so it’s all about evoking emotion

“Do the wrong thing some of the time. Because a melody can be beautiful, it can be dissonant; it can be beautiful in its dissonance, so it’s all about evoking emotion. To me, at least. And if that emotion is not dominant and identifiable as happy or sad, like it’s more abstract or vague, that emotion, then you need to express something that sounds like an abstract or vague emotion.

“There aren’t any words for remembering a loved one who passed away a decade ago. It’s just a random memory. But that might be an abstract emotion that you can’t put into words, so see if you can put it into music somehow, like see if you can get your guitar to resonate that feeling. No matter what you have to do to get to it, if it means like tuning all your strings to one note or something. You have to have fun with it and forget the rules after a while.

“I don’t gauge success as how many people liked the song; it’s about whether I accurately made something that makes me feel a certain way and I can live with it, that I like the finished product at that moment. That is success to me. You don’t need to sell a lot. You don’t need to go viral to have success.”

A Broke Moon Rises is out now via Drag City.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.