Caribou: “Even if a hardware sampler has a slightly different sound, it’s too much of a faff”

Dan Snaith on taking advice from Four Tet and Floating Points, and making new album Suddenly in his home studio

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The phrase ‘home studio’ can sometimes sound a little derogatory, implying a certain amateurishness about the space in which a musician creates their music. For Canadian-born, London-based musician Dan Snaith, however, the ability to place his music-making at the heart of his home and family life is a core part of his creative output.

Snaith first discovered his love of production while growing up in a small town outside Toronto, but it was after settling in the UK in the early 2000s that his musical output really took shape. Over the years, the city’s electronic music culture has slowly become an integral part of the Caribou sound. While early releases - first under the name Manitoba, then as Caribou - blended electronic sampling with influences from progressive and psychedelic rock, it was breakthrough record Swim, in 2010, that saw Snaith nail his own distinctive sound, underpinning those ‘band’ elements with a throbbing club pulse.

In recent years, Snaith has delved further still into the world of dance music with extended DJ sets and a second, club-focused alias, Daphni, resulting in two full-length albums and an excellent FabricLive release.

Now he’s returning with Suddenly - out on 28 February - his first Caribou album since 2014’s Our Love. It’s a record that combines myriad influences, blending modular synths with soul loops, shredding guitar parts and pop radio vocal edits.

As with previous albums, the sound of Suddenly is deeply influenced by Snaith’s circle of family and friends, with his wife acting as a constant sounding-board and the likes of Four Tet, Floating Points and James Holden providing gear loans, inspiration and arrangement advice.

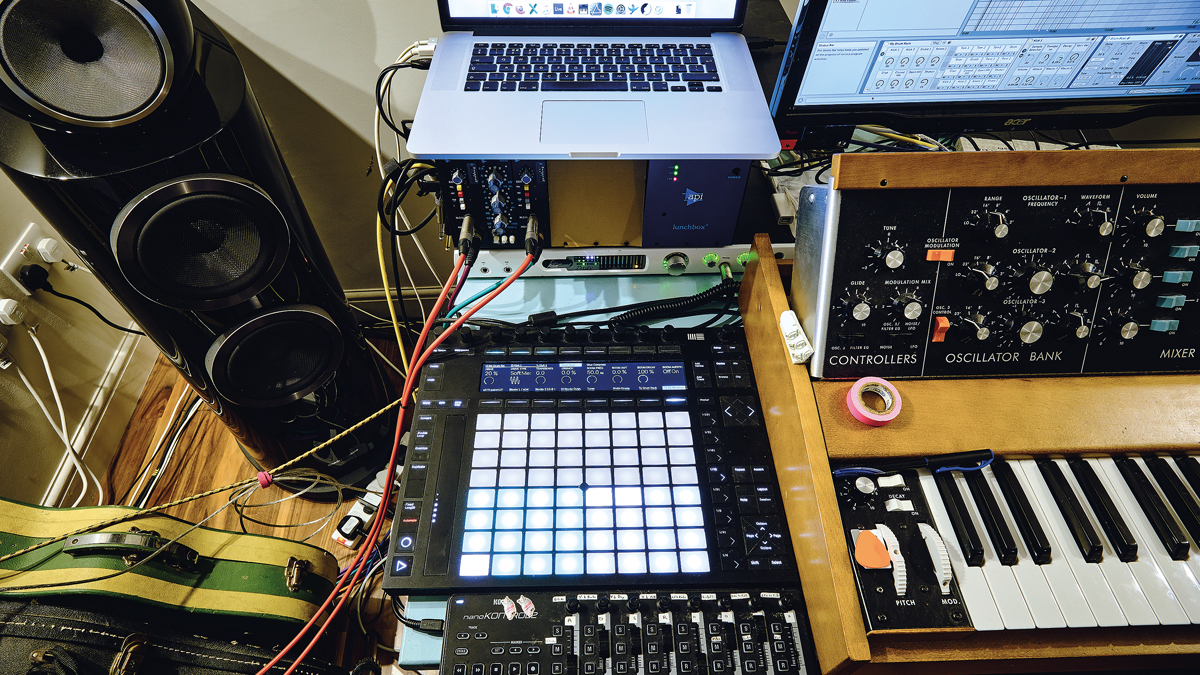

Future Music magazine met up with Snaith in his North London home - complete with basement studio - to find out how it came together.

In terms of its production, how did Suddenly differ from previous Caribou albums?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I guess on a macroscopic level I always have the same process which is, I’m down there [in the studio] writing every day. I really enjoy the first step, which is like generating an idea from nothing. I’ll make two or three 30-second long loops and they just accumulate - every day I make a couple of ideas and then they pile up, and I kind of sieve through them to find the ones that turn into tracks.

“On that level it’s getting worse and worse each time. I can show you that there’s over 900 sketches this time. It’s getting so stupid. I never really understood the people who can just make ten tracks…”

You can’t imagine just making a handful of tracks start-to-finish?

“It requires some kind of crazy foresight and, also, I just figure, if I make another track and choose the best of those two, the result is going to be better than if I had just made the one. It seems like a no-brainer and I enjoy that part, you know? I enjoy the feeling of, ten minutes ago there was no track, and now there’s this ‘thing’. It’s like it’s a kind of alchemy or something. Normally it makes, to continue that metaphor, crap base metal or whatever, but occasionally you get that thing where it’s just like, ‘oh my God, something’s coming out of here’. Sometimes that sticks.”

So the process was broadly similar to your last few records?

“I’ve always worked from home, so in that respect, it is the same as the last album. This album, for sure, comes much more directly, lyrically and thematically, out of the stuff going on in my life the last few years.

“As you can probably tell, music is so integrated into our family life. The kids will come home and be banging on the door and there is no separation sometimes. Lots of people would hate that, but I like it.

“There were a couple of weeks when I went into Sam’s [Floating Points] studio. He was away on a DJ trip and he said, ‘Dan just come in and use all this stuff, it’s just sitting there.’ That was actually really productive, maybe because it was a bunch of new equipment and sounds and things. I can see the appeal of having a separate space, but there’s something about what I want the music to be that just works with my setup. I want it to, kind of, represent me.”

Do you think each album ends up as a snapshot of your home life then?

“Oh absolutely. It’s like a photo album or a diary in some ways. When I look back it will be a good document for me. I know people get different things from music that they listen to, but for me - even though I won’t listen to the album again for a long time - if I were to listen to those old records, it would just snap me back to those things I was going through at the time.”

How conscious are you of creating that snapshot as you’re writing each album?

“It just happens really. For example, Keiran [Four Tet], when he makes an album he has an idea and title at the beginning of the process. He’s like, ‘the idea is grime, radio samples and new age music’ - that was his album Beautiful Rewind - and he can just go ahead and make it.

“For me, it’s completely the opposite. I sit down and get little hints and ideas along the way. The only way I can do it is just by thrashing through it. There’s always this magical moment for me where I get to listen to the album for the first time, which sounds ridiculous. I’ve heard these tracks thousands and thousands of times, but I put them all together in an order and I listen through it and I’m like, ‘OK, this is an album’. It always surprises me, because there’s no intention, it happens as part of the process.”

How far along in the writing process does that usually happen?

“Not until the day when the album is totally done. Before that point, I’m scrambling away and I don’t have time to be spending 45 minutes listening to the whole thing. Obviously, there’s a kind of tipping point when it feels like it’s coming together. But for four out of the five years it just felt like this album was never going to be done. It always feels like that, though. I bet, if they’re honest, that’s the case for most people.

All of a sudden, I’ll listen back to a project and know it’s definitely going to be on the album.

“All of a sudden, I’ll listen back to a project and know it’s definitely going to be on the album. And then another one. And then I’ll have this kind of snowballing moment. This is a really weird thing that’s happened the last few times I’ve made an album. There has always been one night where things just start clicking - I’ll work on something and then go to bed, but I can’t go to sleep because another thing pops into my head. I just have to go down and I work on it. I mean, that’s one good thing about working from home, right?”

You can just duck in and out of the studio…

“I’m literally tiptoeing down the stairs and going back to it. So there is that one moment where I finally know there’s going to be an album. At that point it’s just a case of working out what else it needs. Like the last thing I made for this album, for example, was the first track. I knew I had everything else but it needed an opening track. Sometimes it’s just, like, I need a little entry route to link these two bits together. From knowing the music I have a sense of what’s needed.”

The album title, Suddenly, ties into events in your personal life…

“My wife came up with the title, actually. Because our daughter had just added that word to her vocabulary and she was saying it all the time, which is cute; it was often in slightly the wrong context. Then my wife suggested calling the album Suddenly, because it’s this word that’s just appearing everywhere.

“I went and played the intro track to Sam [Floating Points] - and a couple of other tracks that I had just finished - and he was describing music and kept using the word ‘suddenly’. In terms of the personal stuff, there are a few huge things that have happened that have been the kind of news that you get where the phone rings, you pick it up and then something completely changes in your life.

“And so, again, it made so much sense; it fit with that, but also with the sonic aspect of these weird left turns that are in the music.”

In terms of synths and gear used, does Suddenly differ much from Our Love?

“Our Love was, from my perspective, very polished and shiny sounding: lots of rich polysynths. The world is awash with synthesis right now, it’s inescapable - everywhere you look somebody’s announced a new synth that will have a sound like the Blade Runner soundtrack, or whatever. I was conscious of pulling back from that a little bit, just as a reaction to not wanting to sound like everybody else.

“There was more sampling this time, and there’s a lot of Omnisphere, too. A lot of the guitars on the album are Omnisphere, and the piano as well. As for sampling, there’s a lot of individual sampled hits but also, as you can hear, there are tracks that have whole loops of other tracks within them.

The one big synth on the record is actually something I made. It’s exactly what you shouldn’t do with a modular synth - try and make a polysynth out of it.

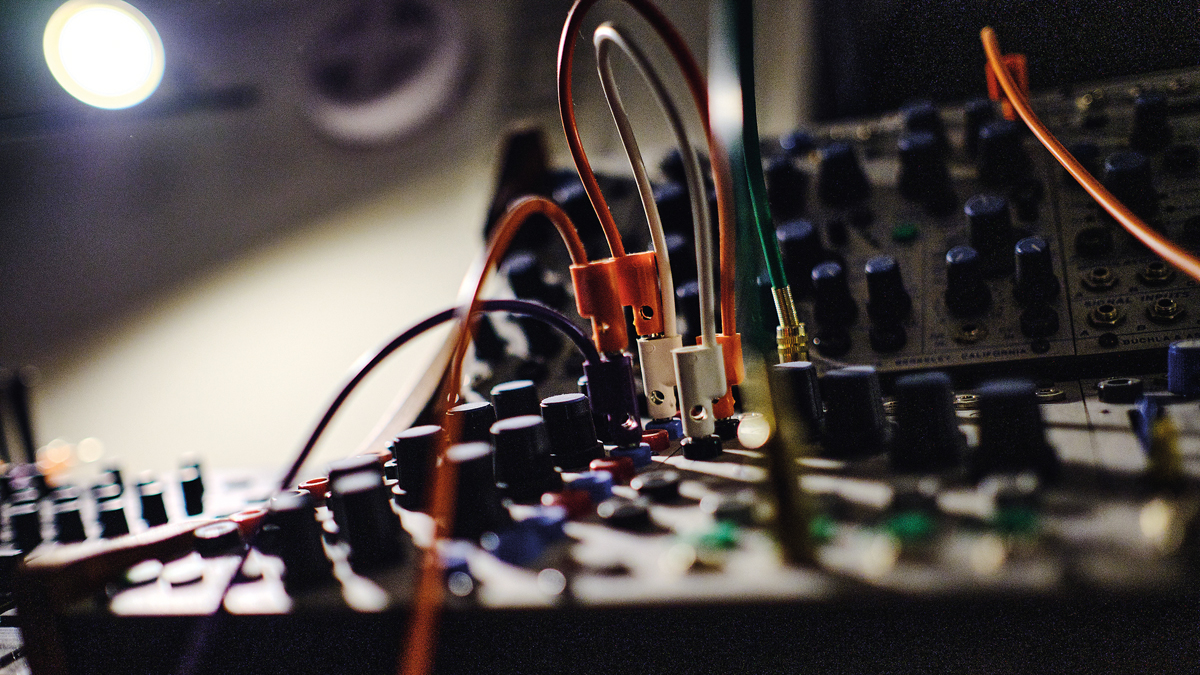

“The one big synth on the record is actually something I made. It’s exactly what you shouldn’t do with a modular synth - try and make a polysynth out of it. I used my modular gear and Reaktor Blocks and I designed this software/hardware hybrid thing. I don’t know if you know the [Synthesis Technology] E370? It has four wavetable oscillators and those route into four filters. I’ve then designed all the CV and control to work in the computer. That appealed to me because you can open a project and still have it remember all those parameters.

“I kind of did it just as an exercise. The thing that I ended up getting out of it is that its four voices can be doing independent things. For example, if you send a Quadrature LFO that’s modulating the wavetable position of each of the four oscillators, you can hold down a chord with four voices, and they’ll all be at different points in the wavetable. That isn’t something that a hardware polysynth can do, as far as I know. That ended up being used for the synth on the first and last tracks on the album.”

You can get extra movement from the wavetable voices then?

“It just sounds a bit odd, and you can do dramatic stuff, like really detune one of the voices in the chord. It has these capabilities and possibilities, and all those ingredients sound nice. It was just a way into something that I could latch on to, you know? That stimulates all these chords and ideas.”

Do you generally let the gear inspire the sound?

“Yeah, I guess it’s a case of making the track based around an instance of an idea. Similarly, there’s a track called Like I Love You that has got what sounds like a guitar on it. It’s actually an Omnisphere bass played in a guitar register on a keyboard, with pitchbend and weird stuff going on. It sounds good because they’ve done everything they can to make it sound like a real instrument, then I’m using it in a way that that instrument could never be used.”

You like using sounds out of context like that?

“Exactly, that’s a lot of the history of electronic music, like the 303 used in a wrong way or with low batteries or, whatever. That was appealing to try whenever I could. Like, with the piano songs, it sounds like a grand piano and then it has these weird pitchbends that you don’t get, obviously, with a real piano.

“For another example, there are a bunch of tracks with that fake guitar sound, but then I also had an actual guitar player on one of the same tracks. It’s subtle but I want it to disorient people. Any guitar players who hear the record would be like, ‘What is going on? You couldn’t play that part on a guitar…’”

Do you work with hardware or software for sampling? You don’t sound like you’re that precious about using one or the other…

“No, I’m not. Magazines like yours - with all due respect - can lead people to the impression that the gear is paramount. I’m sure you as journalists don’t promote that idea but the fanbase who reads this magazine could think, ‘Oh God, if I don’t have this new thing, then I’m never going to make a new track that sounds like whoever’. I’m not like that.

Magazines like yours - with all due respect - can lead people to the impression that the gear is paramount.

“Some of my friends, notably Sam [Floating Points], is the kind of person who will dive deeply into something and understand it completely. James Holden even more so, perhaps. Like, really wring all the possibilities out of an instrument. I’m pretty lazy though. Making this hardware-software-polysynth thing was pretty out of character – me putting that much work into something that hasn’t made a sound yet. It took hours and hours before it was musically productive.

“Even if a hardware sampler has a slightly different sound, it’s too much of a faff. Even outboard is the same. I had a UREI 1176 outboard compressor at one point, but I got sick of having to wire stuff into it and out of it, then compensate for the latency. Fuck all that. I just figure it out with the stuff that’s in the box.

“The first four albums, even most of Swim as well, were all entirely in the box. I had no gear, zero. Like, a computer, a microphone designed for a telemarketer or something, and I would sample stuff off records and use maybe one or two basic crappy synths. But then friends of mine, again James Holden in particular, were doing all this stuff with modular and I was inspired to check that out.

“I’m still resistant to going too far down that path. I’ve also recognised that, something like an OB-8 does not sound the same in plugin form; there is some magic there that can’t be ported across yet. Although, the gap’s getting closer and closer all the time.

“What record would I have made if I hadn’t had this polysynth thing that I cobbled together hardware and software? What if I didn’t have an OB-8? It just would have been a different record. It wouldn’t have been a better or worse record I don’t think. I just incorporate hardware to the degree to which I enjoy it.

“For example, there is a small Buchla rack down there, because, man, how many records do I love that have been made on Buchlas? I can get a sound out of it, but it just seems like too much work. I haven’t used it, and that’s embarrassing; it’s just sitting there but it’s not on the record at all.”

How long have you had the Buchla?

“Three or four years. I can get sounds out of it but they just sound like everybody else’s Buchla sounds. Whereas Sam can do something and get...”

Isn’t his recent album based around his Buchla rig?

“Exactly. He’s dedicated the time to it, he’s understood it, and he’s come out with something unique. Whereas I’m generally not that diligent. I haven’t got anything new from it, there’s no potential for something different. Whereas an Omnisphere guitar with pitchbend is something that I haven’t heard on other people’s records, and was easier to get to. I’m a bit of a magpie in that way. I’m like, ‘Ooh, shiny thing that is easily accessible’.”

Is it fair to say, then, that you prefer to find sounds and re-contextualise them, rather than dig deep into the synthesis side of things?

“Yes, and also the juxtaposition thing is a big one for me. That’s how I’ve got things that I feel are uniquely mine. Listening to Sam’s record and my record, his is far more consistent; he uses the same ingredients over and over again in ingeniously rearranged ways, whereas I might make a track that uses a ’70s stadium drum sound with a shred guitar solo on the end, mixed with my normal kind of Caribou ingredients. I know that’s going to sound different; it’s not going to sound like something I’ve made before because those ingredients are novel to my approach. I think that’s reflected in the albums that I’ve made and how they’re moving around all of the time. They don’t really sound like each other.”

On each album you seem to be incorporating some new influence into your sound, whether it’s psych rock or dance music…

“Some albums that I made in the past, looking back at them now, maybe went too far into this. Andorra from 2007 is a psych rock-sounding record, focused around songwriting and this idea of ‘can I make a psych rock record but on a computer?’. I look back at it now and it’s not that I’m not proud of it, but it feels too close to its references. Whereas Swim, the next record, I felt took a bunch of influences – but then crucially it sounds like me. That’s been a big thing for these last few records, that they have to somehow engage with contemporary music. Otherwise, you know, do we need more people making a ’60s psych rock record when there are plenty of good ones already?”

How does the divide between your Caribou and Daphni records work? When you sit down to produce a track, are you making a decision to work on one thing or the other?

“The main difference is intention. If I make a new Daphni track, it’s usually because I’ve got a DJ gig. For the most part, apart from the tracks that I made for the Fabriclive mix that I did, it’s just that I want to have something new to play. It’s always made to fit in that world of dance music and the circle of friends that I’m imagining - somebody like Ben UFO, or whoever. That’s the intention there, whereas Caribou can contain all that stuff, but it is more like a diary of all of my music tastes and what’s gone on in my personal life.

“Definitely in the last five years I’ve almost always been sitting down to make music with an attitude of, ‘I’m working on the Caribou album’. Occasionally I would make the odd Daphni thing - I put out a Daphni EP earlier this year - but those were all really quick things I did because I was playing a specific gig.

“There’s nothing on this record that could have gone either way. On the last record there was a track called Mars, which could have been Daphni, but in the end it fit the narrative of Our Love. I’m not super precious when it comes to dividing the two things, it just naturally happens because of the intention. And, obviously, on a basic level, if it sounds like a song and I sing on it, then it’s not a Daphni track.”

Your Caribou records have a distinctive vocal sound. How do you go about capturing them?

“The predominant thing about my singing is that my voice is really limited. I can only sing in a small range. Most of that range I can only sing softly in a falsetto. I’m not a natural singer; I never, ever thought I was going to be a singer in a band. It’s absurd that I’ve ended up doing that. But it is something I’m proud of - having found a way of making my voice work with the music that I’m making. That’s part of the reason that it’s consistent, that it’s just prescribed by the limitations of my voice in a lot of ways.

“I’ve got a nicer microphone than I used to have and a better way of recording, but my process is mostly the same as it always has been. The way I record my vocals, I’ll loop two bars and the first thing I do is I sing a vocal with, ‘la la la’, some kind of nonsense syllables. Then, by the point that I’ve written the lyrics, I’ll take a two-bar loop with one phrase and sing it 100 times over and over again. If you do that, it just improves. You can tell if you listen to the first time you’re singing and the 80th time.

“After that I have this laborious process of lining them all up, going through and chopping. It’s a Frankenstein job, chopping these three words from one take with that word from another. They might all be OK but some of them naturally just have more ‘something’ to them. I do that through the whole song, so recording vocals is one of the things right at the end and it’s something that I kind of dread.

“I feel comfortable on a keyboard instrument; I feel like I can generate ideas, but with singing I’m constantly banging up against my limitations. But that is part of what makes it sound the way that it does and lets me get the emotion into it that I do. That battle, trying to make it happen, is an important part of it for me.

“Saying that, this time around, I actually ended up really enjoying it; that process of just dialling my attention into what’s going on in my voice.”

Do you ever find it’s difficult to be objective, as a producer, when dealing with your own vocals, compared to a synth or drum line?

“It goes away. To some degree it’s gone away over the years because I just get used to what my voice sounds like on record. But also, by the time I’ve worked on a song for months and the vocal’s been there for months, it’s almost like I’m listening with an engineer’s ears rather than a producer’s ears.”

So you’re able to get that separation?

“Yes, I can listen pretty objectively, I think. There are definitely points on this record where either Keiran and I or, particularly, my wife and I, have disagreed. She’s like, ‘definitely do those vocals over again’, and I’ll say, ‘I think it’s OK that it’s not perfect’. That’s part of the character.”

You mentioned you use Keiran Hebden [Four Tet] as a sounding board. He contributed to the arrangement of lead single Home, too. Is that the first time he’s done that for you?

“That’s the only time that’s ever happened. There’s a section with a breakbeat at the beginning, then when the vocals come in it’s this much more mellow version of the same thing. Originally, I’d made a version that had the breakbeat banging away the whole way through, and I’d made a version that was super mellow the whole way through. I’d done those months apart, but Keiran kept all of these things that I’d sent him and came up with this version that went back and forth, more of a verse-chorus, which in retrospect is an obvious thing. I’d lost perspective on it. In his email he’d already attached something; he was like, ‘it was just easy for me to splice together exactly what I’m hearing in my head’. So, he’d cut the two into one track.”

He did the edit himself, then?

“Exactly. Also, some of the little, weird Madlib-style stuff is his. Where [the breakbeat] drops in for a bar, or half a bar, or it comes in a bar before you expect it to. He’s so insightful with that kind of stuff.

“I then went back into the project and replicated what he’d done by splicing things together, so that I could work on it and change it further. That’s the only time he’s ever been hands-on like that; normally he just describes what he thinks something needs.”

How much does performing live as a band influence your decision-making in the studio?

“I refuse to let it - that was a decision I made a long time ago. We [Caribou] started touring as a band in 2003 and before that point I hadn’t thought that that would be something that we would do at all. I made a decision that I wouldn’t make or not make any track just because it would be impossible to play live. The records are their own things and if there’s some tracks that we can’t play because they were put together in a way that won’t translate live, that’s fine, we just won’t play those tracks.

“Saying that, though, when making Can’t Do Without You, or Never Come Back on this album, it’s definitely impossible not to think, ‘this one is going to be fun to play at a festival’. But you can hear from the record, it’s clearly not the primary driver.”

It’s obviously not an album built for a ‘band’...

“It’s not built for a band; it’s not built for big rooms or festival stages. But, having said that, from years of making music there are now enough tracks that I’ve made that we can play in lots of different contexts. We can play at a dance music festival, we can play at Glastonbury, we can play a small club and play more intimate music. I feel like that’s really lucky.

“My decision to not let that dictate everything has meant that we aren’t really pigeon-holed in the way that our live show will work. We can play next to a folk singer-songwriter, but we’ve also played in Ibiza and in clubs where people like Loco Dice are after us. I enjoy that - being able to have a wide range of things that we can do.”

What’s your role personally, when you’re up on stage with the live band?

“I’m singing most of the songs, obviously, and I’m playing lots of synthesizer parts. I also play drums. Sometimes, we’re all triggering samples or one of us will be modulating parameters on an instrument that somebody else is playing. We don’t have fixed roles but, I guess, most of the time I’m playing a keyboard.”

Has the make-up of the live band remained fairly consistent over the years?

“It’s all of the same people. Ryan who plays guitar and synths in the band was in my first band that I was in in high school. He was the one who first said we should start playing [Caribou] songs as a band. He’s been in it forever.

“Brad, who plays drums, was in an opening band that played for us in 2000 - he joined the band in 2007. And John, who plays bass and sings, joined in 2009.

“Those guys don’t appear on the records. It’s kind of like that is a dividing line - I make the records myself, but the live show is very, very much a collaborative thing. We live in very different places - Toronto, San Francisco, LA, here in London - so right now there are a million different Ableton projects being sent around. Then we have a month of rehearsals coming up.”

You’re collaborating remotely on how the set is going to come together before you get together?

“Yes. And it’s not me telling them, ‘you do this’. I trust them because we’ve played together so long and we’ve had this experience of reverse engineering studio things for live, which is not that hard these days. Live electronic music performance was, when we started, next to impossible, but now the capabilities make it much easier.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.