Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“Writing a song like this can be deceptively easy,” Bob Dylan wrote in 2022. “First you assemble a list of things people hate. For the most part, people are not going to like war, starvation, death, prejudice and the destruction of the environment…”

Dylan was writing about the Temptations’ Ball Of Confusion, written by Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, but maybe it gives us some insight into how he now views the songs of his younger self.

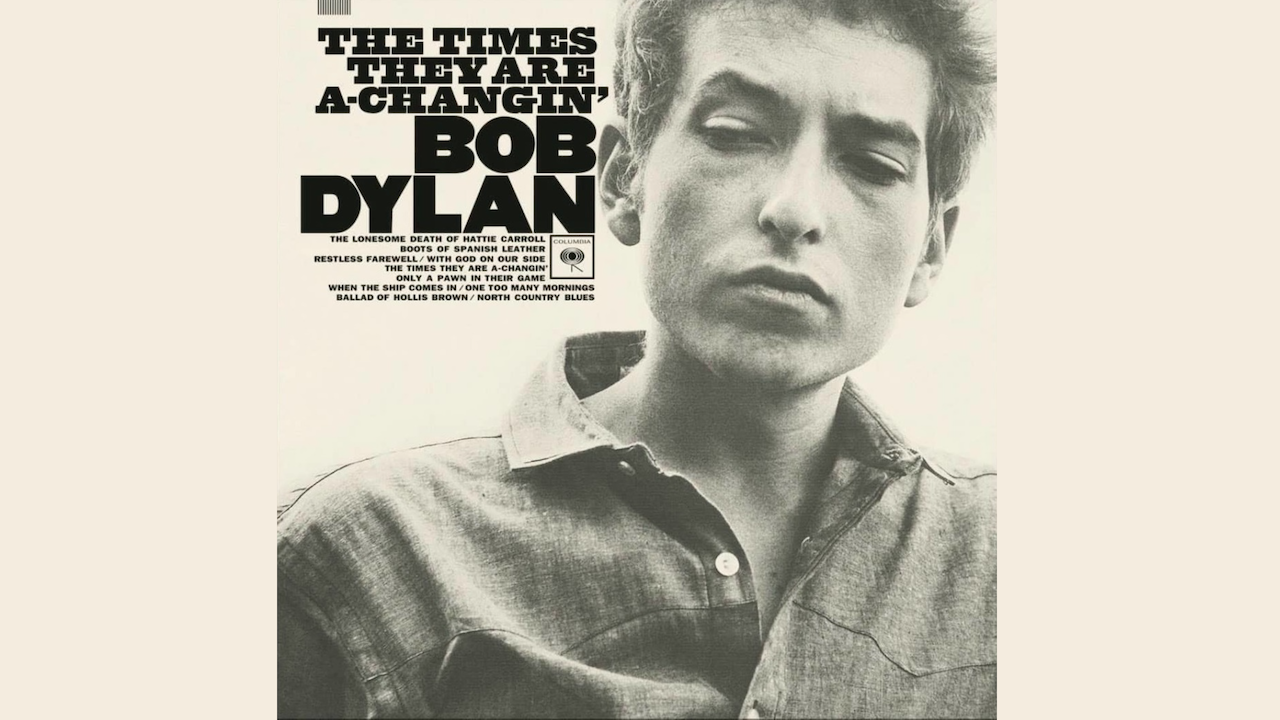

On 23 October, 1963, aged just 22, Bob Dylan went into Columbia Records Studio A in New York, and made his first attempt at recording the song that would become the title track of his third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’. On 24 October, he nailed the version we know today.

There were no other musicians: just Dylan, an acoustic guitar (most likely the Gibson J-50 he’s photographed with on the cover of his debut album, but possibly the Gibson Nick Lucas Special, a 13-fret acoustic that he bought in late ‘63) and a Hohner Marine Brand harmonica.

Along with Blowin’ In The Wind, Masters Of War, Ballad of Hollis Brown and several others, The Times They Are A-Changin’ made him the foremost folk singer of his day – a young gunslinger that connected the 60s generation with the American Folk Music Revival, led by the likes of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Leadbelly and Dylan’s relative contemporaries like Joan Baez and Odetta.

In 2015, accepting an award from music charity MusiCares, Dylan talked about where his songs came from. They didn’t just come of out thin air, he said. One of his early music publishers, Lou Levy, had said there was no precedent for Dylan’s songs. Dylan disagreed: “Contrary to what Lou Levy said, there was a precedent. It all came out of traditional music: traditional folk music, traditional rock ‘n’ roll and traditional big-band swing orchestra music.”

His 2022 book, The Philosophy Of Modern Song – with analysis of songs from everyone from Perry Como to The Clash – shows Dylan’s love for the craft of songwriting. Even as a young man, he had an interest in songs of all genres, no matter how old the song.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I learned lyrics and how to write them from listening to folk songs,” he said. “And I played them, and I met other people that played them back when nobody was doing it. Sang nothing but these folk songs, and they gave me the code for everything that’s fair game, that everything belongs to everyone.” [Our italics]

The Bob Dylan of 1963 was deeply influenced by folk music and Irish rebel songs. Dylan was hanging out at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, an Irish bar where the locals and ex-Pats sang songs from the old country.

“All through the night they would sing drinking songs, country ballads, and rousing rebel songs that would lift the roof,” he wrote in his book Chronicles (2005). “The rebellion songs were a really serious thing. The language was flashy and provocative – a lot of action in the words, all sung with great gusto.”

The Irish songwriter Dominic Behan accused Dylan of plagiarising the melody of his song The Patriot Game and reappropriating it for The Times They Are A-Changin’ album track With God On Our Side. Dylan never responded. Like he said: “Everything belongs to everyone.” The melody of The Patriot Game itself, owes a possible debt to the 17th century folk song, One Morning In May.

This kind of musical borrowing was rife. English folk guitarist Martin Carthy saw his arrangement of Scarborough Fair become a hit for Simon & Garfunkel. He described it as a musical cross-pollination. “We [British musicians] were learning techniques from the Americans,” he told Guitarist magazine. “Anyone who wanted to play guitar had to go to them to learn the techniques. The first guitar player I ever learned from was Big Bill Broonzy, I borrowed all his EPs from my mates.

“In return, we gave the Americans songs… The English actually changed Dylan’s way of writing songs. His first album, Bob Dylan, was basically little blues bits and pieces with the occasional American version of a folk song thrown in. His second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was almost finished when he came to England in 1962. When he went back home he wrote at least two songs to complete it. One of them was Bob Dylan’s Dream which he learnt from me singing a song called Lord Franklin. Another was Girl From The North Country, which derives from Scarborough Fair.

“Boots Of Spanish Leather from Times They Are A-Changin, that’s got London in it somewhere… I don’t know where, I’ve just got a hunch. The whole of that album’s smothered in this shift in musical direction. The tunes are far more expansive, they’re more of this side of the Atlantic. Dylan was a piece of blotting paper, he still is. He hears stuff and he just gobbles it up and out it comes in another form.”

“For three or four years all I listened to were folk standards,” said Dylan. “I went to sleep singing folk songs. I sang them everywhere, clubs, parties, bars, coffeehouses, fields, festivals. And I met other singers along the way who did the same thing and we just learned songs from each other. I could learn one song and sing it next in an hour if I’d heard it just once.”

“You use what’s been handed down,” he said once. “The Times They Are A-Changin’ is probably from an old Scottish folk song. I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.”

The melody for The Times They Are A-Changin’ is indeed from a Scottish folk song: Hamish Henderson’s The 51st (Highland) Division’s Farewell to Sicily. In turn, the melody of that song is by its author’s admission, taken from an old pipe tune Farewell To The Creeks from around 1915.

Even the title of The Times They Are A-Changin’ was borrowed. It appears to have been suggested by Das Lied von der Moldau aka The Song of the Vltava, a poem by Bertolt Brecht that was set to music by Hanns Eisler. It was originally entitled The Times Are Changing, and appeared in a production called Brecht On Brecht that Dylan’s then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo worked on in the spring of 1963, a production Dylan definitely saw. In fact, Brecht's poem might have gifted more than just the title.

“The times they are changing,” goes the second verse, “Magnificent plans of/The mighty will come to a halt in the end/And are they still crowing like some bloody roosters/The times they are changing, and no changing that.”

Dylan thought it was all fair game. In his poem 11 Outlined Epitaphs, which ended up being published as liner notes on The Times They Are A-Changin’ album, he wrote: “Yes, I am a thief of thoughts/not, I pray, a stealer of souls/I have built an’ rebuilt/upon what is waitin’/for the sand on the beaches/carves many castles”.

The sand on the beaches – the raw materials of songs – builds many castles. The trick is to be alert to inspiration (“a word, a tune, a story, a line/keys in the wind t’unlock my mind”). "Words wrapped in tunes," he said, are just waiting for him to "reshape them an’ restring them”. It was his aim, he wrote, “t’ make new sounds out of old sounds/an’ new words out of old words”.

In 2015 he was even more explicit: “I sang a lot of ‘come all you’ songs,” he said of his early days as a folk singer. “There’s plenty of them. There’s way too many to be counted. ‘Come along boys and listen to my tale/Tell you of my trouble on the old Chisholm Trail.’ Or, ‘Come all ye good people, listen while I tell/The fate of Floyd Collins a lad we all know well…’

“‘Come all ye fair and tender ladies…’ ‘If you’ll gather ’round, people/A story I will tell/‘Bout Pretty Boy Floyd, an outlaw/Oklahoma knew him well.’

“If you sung all these ‘come all ye’ songs all the time,” he said, “you’d be writing, ‘Come gather ’round people wherever you roam, admit that the waters around you have grown…’

“You’d have written them too. There’s nothing secret about it. You just do it subliminally and unconsciously, because that’s all enough, and that’s all I sang. That was all that was dear to me. They were the only kinds of songs that made sense.”

There’s no secret about it, says Dylan. The sand on the beaches builds many castles. Only sometimes you have to look backwards – to ancient old melodies, to long forgotten lyrics – to go forwards.

Tom Poak has written for Guitar World, Total Guitar, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Esquire, The Big Issue and more. In a writing career that has spanned decades, he has interviewed Brian May, Brian Cant, and cadged a light off Brian Molko. He has stood on a glacier with Thunder, in a Norwegian fjord with Ozzy and Slash, and on the roof of the Houses of Parliament with Thin Lizzy's Scott Gorham (until some nice men with guns came and told them to get down). He has had a drink with Shane MacGowan, mortally offended Lightning Seed Ian Broudie and been asked if he was homeless by Echo & The Bunnymen’s Ian McCulloch.