"It's often more difficult to play with a consistently even feel at slower tempos than fast ones": 10 tips to help drummers to develop better timing

Smooth-out your timing and you'll make everything easier. Here are some practical ways to get your inner clock ticking

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

DRUMS WEEK 2025: They say it’s the secret to great comedy, but timing is also a fundamental skill for drummers - and all musicians - that requires development. But this isn’t a set-and-forget, box-checking ability. Your inner sense of timing is like muscle memory, and you’ll need to maintain it whether you’re a beginner or seasoned pro.

But what if you’re starting from a point of fluctuation? First, you need to iron out your playing, and this can stem from the way you’re perceiving tempos in your mind to individual limbs physically out of sync with each other.

Sadly, there is no real shortcut for this, it’s something that will come over time through plenty of practice with a metronome and repetition, but that doesn’t need to mean that you’re going to spend forever playing single-stroke rolls tethered to a fatiguing quarter-note pulse (although a bit of that won’t hurt).

Let’s look at some ways to put some fun and thought back into developing one of the most important areas of your playing.

1. Listen to your playing, honestly

If you’re already thinking about needing to work on your timing, chances are you have experienced an issue that brought you here. Whether it’s something you’ve noticed, or the result of a comment from other musicians, try not to let it get you down. You’re looking to improve, which by its very definition means there’s something you need to change.

So, the first step is to record yourself playing to a metronome at various tempos. You don’t need any fancy gear to do this - your phone’s video or voice recorder will do just fine, as long as it’s capturing a clear recording without massively overloading the microphone. If you’re using an electronic kit this is made even easier by the built-in metronome and recording functionality.

The important part is in the listening. Whether your recording captures the click or not, you should be able to identify tempos where your playing starts to rush or drag. This commonly occurs when transitioning between grooves and fills, but it can also be present during general ‘time’ playing.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Listen to the individual parts of the kit - are your limbs hitting in sync? Are your hi-hat/ride sub-divisions consistent? Are your left and right hands playing evenly when it comes to moving around the kit? These are the types of things we need to get right.

2. Set your goals, and stick to them

This is obvious, but once you’ve identified the areas you need to focus on, it’s time to create yourself a plan. The first thing to identify is your end goal. It’s important to remember that good timing takes time, so even if you’re trying to build up hand-to-hand speed, you need to start slowly.

Sixteenth-note fills at faster tempos will become a lot easier if you’ve put the work in to play consistently and evenly at lower tempos. Practice at set tempos for a decent amount of time, and gradually increase the speed by a few BPM each day. Over the course of a month you’ll cover a lot of ground, but you won’t notice the jump.

The same applies if you’re looking to improve your note spacing within a groove. Start slowly, pay attention to the note spacing and move up in small 3-5 BPM increments each day.

Most importantly, keep motivated! Just as with working out, you won’t notice improvements immediately, but with a disciplined approach you will start to see a difference. If it helps, record your progress to listen back to - you’ll be amazed how much better you’re getting over time.

3. Double down? Double up!

Playing at faster tempos may seem like the greater physical challenge, but it’s actually (when it comes to timing) often more difficult to play with a consistently even feel at slower tempos.

This is because the gap between crotchets at say, 60BPM are a lot long than they are at 190BPM. With a metronome set to quarter-notes at slow tempos, the slower you get, the greater the room for error becomes. So to overcome this we need to reduce the space between pulses.

You can do this by choosing a slow tempo (let’s stick with 60BPM), then doubling the speed you set the metronome (120BPM). Now, you’ll have an eighth-note pulse at 60BPM, halving the gap and giving you twice as many increments to lock to.

Of course, if your metronome has a subdivision control, you can use that to create the same outcome. Choose eighth-note or sixteenth-note modes to give yourself a greater resolution from your metronome, and unlike many timing-based exercises, you should notice a fairly immediate difference!

4. Mind the gap!

The ability to lock-in with a metronome is a valuable skill for any musician, but what if you’re trying to develop your clock for those times where you won’t have the safety net of a click? That’s where using a ‘gap click’ can really help you to train your brain and muscle memory.

The idea is straight forward - start off with a metronome at the tempo you require. You play in-time with the click, and then it drops out for a bar. If your inner clock is ticking properly, you’ll continue to play in time and then the click will restart on your first beat.

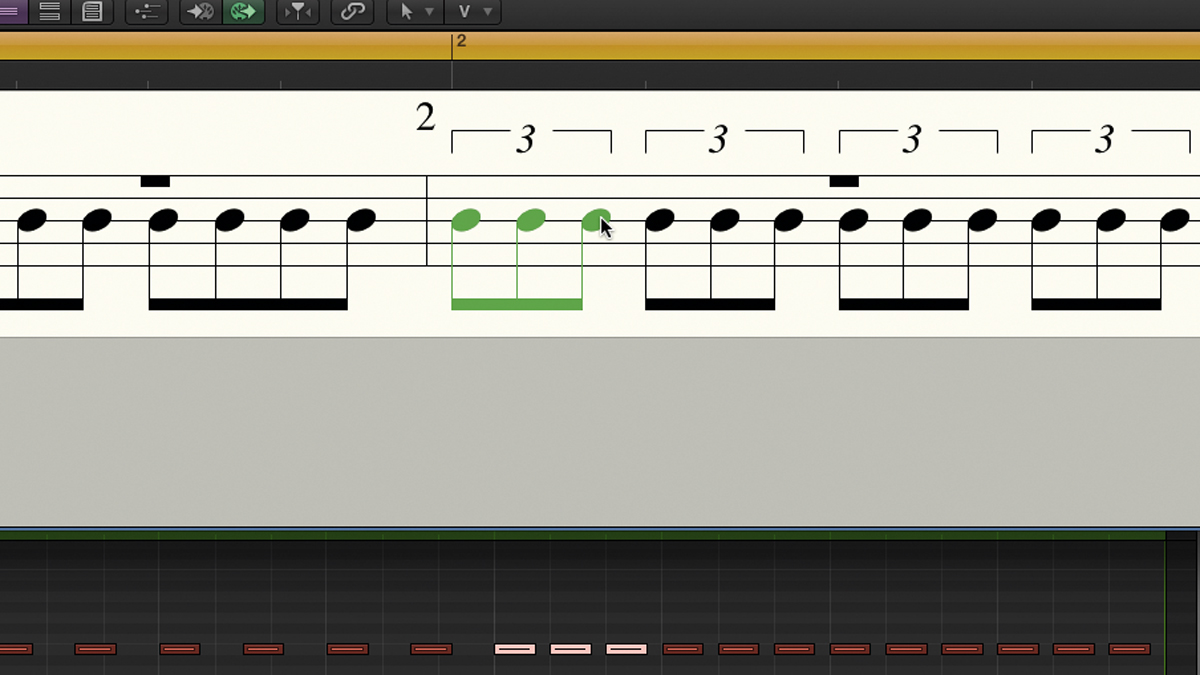

Don’t have a metronome with this function? Don’t worry, most don’t. If you have a DAW, you could program your own, with progressively longer click dropouts.

But if that sounds tedious, drummer extraordinaire Benny Greb developed his own Gap Click app to provide us all with exactly that. It costs £2.99/$2.99 and is available for iOS via the Apple App Store, or Android via Google Play.

5. Play to recorded music

Ok, so the thought of The Beatles, James Brown or The Rolling Stones being gridded to a click is enough to make die-hard music fans burn their records. However, consider that since the age of digital recording, the vast majority of commercial music has been created to a metronome.

This not only creates a consistent tempo, but it means that incorporating MIDI devices and samples, as well as automated effects and production decisions is much simpler. The benefit for us as drummers is that if playing to a click gets old, fast, we can still work on our timing in a more musical way by simply playing along with recordings.

Make a ‘timing playlist’ incorporating music you like at different tempos - it can be any style - and play along. You don’t have to parrot the drum beat, but do try and regiment what you’re playing.

If you’re working on your timing within grooves, play grooves and keep the fills sparse. If you want to develop your fills, you could try playing single-strokes, double-strokes and paradiddles around the kit, if it’s transitions between both, mix it up.

6. Don’t forget the feel

One of the biggest criticisms of metronomic timing is that it feels rigid and sterile. This can sometimes be because when we play to a metronome, we're so focussed on keeping time, we overlook important things such as dynamics. So it's worth paying attention and making sure you're still playing musically, with accents where they should be etc.

But accurate, consistent timing and 'feel' aren’t really the same thing - being able to keep a solid pulse is one skill, injecting ‘feel’ is another. Feel comes from myriad ingredients - our inner clocks, how we hear the pulse, its subdivisions and the way we execute our playing in relation to the rest of the band.

It incorporates dynamics, orchestration and creativity as well as timing. John Bonham’s ‘behind-the-beat’ playing injects a laid-back pulse to his grooves, but it’s still consistent within its own scale. So, to develop feel, we first need a strong sense of timing (achieved by internalising a range of tempos through practicing with a metronome), but that doesn’t mean that we should ignore the ‘feel’ drummers.

Just as with your timing playlist, consider creating one incorporating music that definitely wasn’t recorded to a click. This is where you should try and recreate the beats as closely as possible, that way you can begin to understand the more detailed timing elements that make Bernard Purdie different to Keith Moon.

7. "Not quite my tempo"

This tip is less about your actual development, and more about when it comes to putting it into real life scenarios. We’ve likely all experienced other band members insisting on counting-in songs at what we perceive to be the wrong tempo, which can lead to a very jarring feel as each instrument jostles to find its natural pulse.

Similarly, we’ve probably all got to the end of a song we’ve counted-in to be told ‘That was too fast/slow’. Who’s right and who’s wrong isn’t important, and as with most things, the reality probably lies somewhere in the middle as the adrenaline of performing with others - particularly in a live environment - can mess with our clocks.

But, if you want to avoid tempo-based arguments, make a note of the speed you’re playing songs in practice - if it’s a cover or you have your band’s original recording, start there - then use it as a reference when you start the song.

Plenty of metronomes have a tap-tempo function which can be used to quickly determine the speed of a song. If not, websites such as TapBPM will have you sorted quickly.

If your timing is being questioned for fluctuating, apps such as liveBPM can be a useful adjudicator. You load it onto your phone and play while it monitors the tempo, which is displayed on the screen for all to see, removing (or hopefully not confirming) any doubt!

7. Don’t just play it straight

So far, we’ve focussed on simple, ‘straight’, timing. But that’s only part of the story. Shuffles and swung music are going to rely heavily on a triplet feel, but you should also apply triplet subdivisions against straight pulses to iron-out the transitions between different note values.

You can do this in a similar way to the first tip by utilising the subdivision function on your metronome. If it allows, you could also stick with the odd numbers by trying subdivisions in fives, sevens and nines to really help yourself become comfortable with these more uncommon - but still useful - divisions.

9. Move the accent

Most metronomes are pre-programmed to provide an accented pulse in the most logical place in the bar - on the downbeats. But if you’re working on syncopation (accents that don’t fall on a downbeat), you might find it useful to have the accent elsewhere in the bar.

The quick way of doing this (if your metronome doesn’t allow you to select where accents are placed) involves tricking your brain slightly by setting the metronome, then ignoring that the accent is a downbeat.

Count from a different spot so that the accent now arrives on your chosen subdivision in the bar (the ‘e’ or ‘&’). Once again you might find it easier to program a click track in a DAW in order to place the accents where you want them. Using this method can really help enforce your sense of where the offbeats need to fall in relation to the down and backbeats.

10. Go electric!

If you’re lucky enough to own an electronic drum set, you already own some powerful time-building tools at your disposal. That’s because kits from the likes of Roland and Yamaha come with coaching/training modes built in.

You may have overlooked these modes as beginner lessons, or perhaps you’ve just forgotten about them. But with functions such as a timed gradual increase/decrease in tempo, a ranked score of how well you’re striking in time with the click, gap-style click functionality and even silencing of your hits when you fail to play on the beat, these tools are worth another look.

It’ll take the monotony out of playing to a metronome, and you’ll be able to see your progress (and what you need to work on) right there in front of you.

Stuart has been working for guitar publications since 2008, beginning his career as Reviews Editor for Total Guitar before becoming Editor for six years. During this time, he and the team brought the magazine into the modern age with digital editions, a Youtube channel and the Apple chart-bothering Total Guitar Podcast. Stuart has also served as a freelance writer for Guitar World, Guitarist and MusicRadar reviewing hundreds of products spanning everything from acoustic guitars to valve amps, modelers and plugins. When not spouting his opinions on the best new gear, Stuart has been reminded on many occasions that the 'never meet your heroes' rule is entirely wrong, clocking-up interviews with the likes of Eddie Van Halen, Foo Fighters, Green Day and many, many more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.