“I love figuring out not just what ‘should’ this album be, but what ‘could’ it be”: Katie Tavini on the secrets behind top-class mastering

A ubiquitous name in the world of mastering, Katie Tavini’s intuitive senses and aptitude for bringing out the best in a huge array of music has been rightly praised

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While we naturally focus a great deal on writing, arranging, sound design and mixing here at MusicRadar, the world of mastering can sometimes get overlooked. Central to why this is could be down to both the numerous variables that each project presents – and the reliance on the ears and toolset of the mastering engineer in question. So much of how a final master sounds is down to creative decisions based on determining what a track ‘could’ become.

A key figure in the mastering arena for over a decade, Katie Tavini understands all too well that the process of finalising a track for the ears of listeners relies heavily on bringing out the best from the mix. Around 11 years ago, we published the very first print interview with Katie, and since then, she has gone on to work on records for the likes of Bloc Party, Rudimental, Ash, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Nadine Shah and Arlo Parks, gaining a slew of nominations at the MPG Awards along the way. She’s also founded her own mastering collective, dubbed Weird Jungle.

After such a productive decade, we were keen to catch up with Tavini. We start with the obvious – why mastering? “I don’t think I ever really decided,” Katie says. “I think it just happened. I was working as a recording engineer and that was sort of my world. I just really accidentally fell into mastering, but realised that I really enjoyed the process and listening deeply. I knew I had a lot to learn, though. It’s been a decade of lots of learning, lots of growing and building my career in a direction I never even considered when I was younger.”

The master plan

Katie explains that her household was a place of constant music, with her dad’s penchant for playing records making the young Katie well-versed in the qualities of well-produced albums. “I just really liked sound from a really young age,” Katie explains. “My grandad had a cassette player and it came with one of those little microphones where you could record stuff. I used to do that and play the sounds back. I don’t know why I was really drawn to sound, but from being really young it was something I was interested in.”

Was Katie writing music herself at that point? “Well, I did try, but that’s not for me!” she laughs. “If you’re interested in music as a teen, the really obvious route is to try and make music. That’s what I was doing and that’s what my friends were doing. It was really, really clear to me that, actually, I didn’t enjoy it. I was really interested in going to gigs when I was 17, and seeing what the live sound engineer was doing, and watching what the technicians on stage were doing – that was more interesting to me than writing a song.”

Tavini views the mastering process as akin to playing an instrument, and spends time practising different mastering techniques when not actively engaged in projects: “I do it each week. I always want to get better and I never want to coast. I don’t want to feel like I’m stuck, or not improving.

“Anyone can learn how to master,” Katie continues. “But it’s only recently that it’s started becoming accessible. People can master on a laptop with headphones and can do – and are doing – phenomenal work. It’s amazing. That barrier of being in a fancy studio with fancy gear is not really the case anymore. It is critical listening, though, and so much of mastering is based on taste. The best mastering engineers have the best taste in music. They just absorb so much music. I think if you don’t have a really broad taste in music you’re probably not going to enjoy being a mastering engineer. You don’t really specialise in genre – when you’re working on an album a day, you can’t say, ‘I only want to work on punk records’. There won’t be enough work.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Everything that I work on, I try to find something that I really love about that music

Katie continues, “Every single thing that I work on, I try to find something that I really love about that music. When people assume mastering engineers are just ‘listening to music all day’, we are, but if you’re not really open-minded then you’re going to struggle. Whereas for mixing and recording engineering, you do get people who tend to specialise in genre.”

What the music needs

With her mastered records spanning multiple genres, we ask Katie if her toolkit changes depending on style and intensity? “I definitely view each job as its own thing,” Katie says. “I don’t have a go-to process or a go-to mastering chain. I’m not a very technical person. I’m approaching mastering as a music fan. I’m going to a gig tonight, I went to a gig last week. I’m in the music world. I’m coming in with a mindset of ‘how do I want to hear this as a fan of the artist and as a listener?’ I’m trying to find what the music needs. Sometimes, it’ll need very little. Sometimes it’ll just need something creative.”

Katie cites her recent work on Los Bitchos’ La Bomba as a good example, “I had a FaceTime with the producer, Oli-Barton Wood, and he was saying ‘this is how I’ve produced it, but I feel like it could go in a completely different direction for mastering – can you make it weird?’. He gave me creative freedom. We played with a lot of ideas – it was this beautiful, collaborative process. I love really exploring the sonics – figuring out not just what ‘should’ this album be, but also what ‘could’ it be?

“Sometimes mastering is more reigned in than that. Often artists have a really clear idea of what they want in their heads, and it’s your job to make that happen. I worked with a producer earlier this week for a band, and he was telling me that he could only get to a certain point with the mix, and asked me how to make it go in the direction that he had in his head, but wasn’t quite happening in the mix. It turned out making what I first assumed was a rock song, into a poppy, sparkly track, made it work. I’m not a mind-reader, but sometimes you know exactly which direction to take something.”

On the strength of Katie’s open-minded approach, it’s understandable why so many people have returned to let Tavini helm the master. “I think when you’ve been working with people for over 10 years, like [I have with] some of my clients, you know what they want and like,” she says. “But that does come from having had a lot of those conversations in the past. Now, there’s people I can just dial into and I know what their taste is and I know what to do. Sometimes when people book in, they’ll send a reference track, or tell me directly what they want it to sound like. I do always find it nicer when people are open to a conversation.”

Tavini’s tools

Having recently moved studio from her jungle-themed Brighton studio to a home-based setup in Liverpool, we ask Katie what the key toolkit consists of? She begins with that most crucial aspect – the monitoring: “I’m using the PMC TwoTwo.6’s as my main monitors. I’ve had them since 2018 and I’ve heard different speakers – cheaper and much more expensive, as well as fancy headphones – but I feel like these just suit my work. I know them so well, and I’ve gotten to know my new room so well.”

Mastering is lonely, but I’m sat in here every day, living the dream, working in music

Moving on to the outboard, she tells us: “I’ve got the IGS Audio Tilt n Bands EQ, as well as a Manley Massive Passive. That was cooking my knees, which is why there’s now a blank space above and below it – it gets really hot! I’ve got the Lynx Hilo and I have this Amek Medici Mastering EQ which is probably my favourite thing that I own. They’re not super-common. I think only around 50 were made. It was Rupert Neve’s first project when he started working with Amek. It sounds like nothing else I’ve ever used. Then, I’ve got the SPL 1520 Iron, which is covered in cat hair at the moment. Under my desk, I’ve got the Bettermaker Mastering Limiter, which is plugin-controlled. I don’t need to look at it, but it’s there in the loop!”

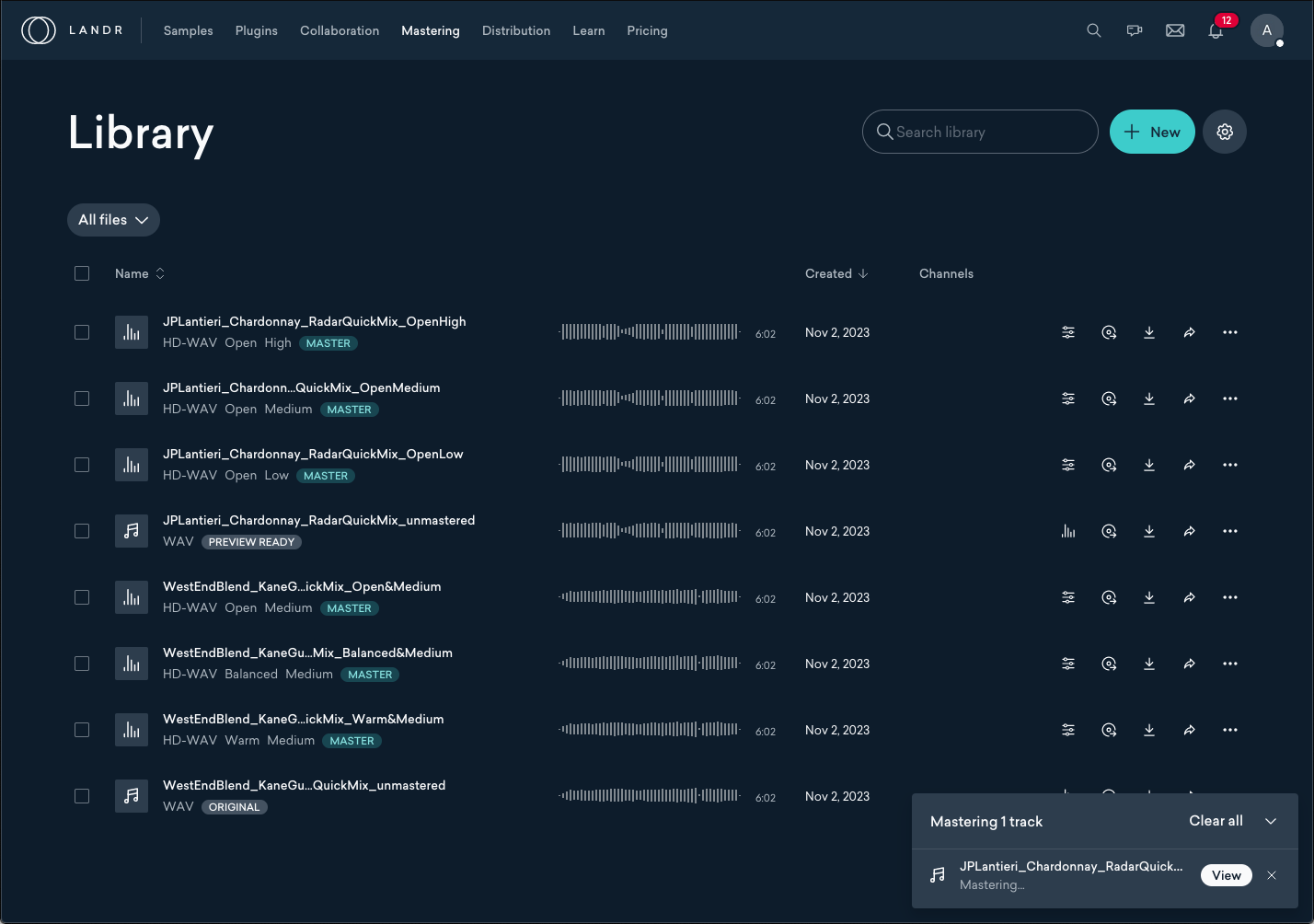

In terms of her central software mastering workstation, Katie relies on Steinberg’s WaveLab: “I’m just on version 8.5. I was the actual face of version 10 or 11, but it does so many things that I don’t actually need. 8.5 runs really well. I used to work at the British Library as a transfer engineer there, we were on 9.5 when I was working there. There was so much functionality that suited that job, but for mastering I’ve always come back to 8.5 because I don’t need anything else. I’m one of those kinds of people that has like four plugins. I don’t have a lot of stuff really. I don’t want to be overwhelmed by gear. I want to be able to open a limiter and know exactly how to get the sound that I’ve got in my head.”

“Mastering is so quick,” Katie explains. “If I’m not doing an album a day, then I’ll be doing 10 singles. I need to know that if I’m opening up a plugin, I know exactly how it works and how I would get the best sound from it. I don’t want option paralysis. If something does what you need it to do, then that’s all that matters really, isn’t it?”

Tavini tells us that, in all honesty, for her the hardware is where it’s at, though she has compared and contrasted the outputs of emulations vs real gear. “I work with two other engineers, Stephen Kerrison and Izzy McPhee,” she says. “Stephen and I did a couple of tests. We tried to compare the hardware versions of the Massive Passive and SPL Iron against the software versions. Obviously, when you’re comparing those things, you have to account for conversion and all of that stuff, but the Massive Passive, we couldn’t recall the setting exactly the same, so we were being quite approximate with it. We did conclude that the hardware version sounded loads better. With the SPL Iron, we recalled exactly the same settings and the difference was totally negligible. There wasn’t a big difference at all.

“Mastering is lonely though, I’m sat in here every day – I’m living the dream and working in music, but if I was just staring at a computer screen all day, every day I’d have less fun. It’s much more fun to be hands-on with things. I feel like I can get a sound out of my head and into my speakers easier with outboard gear. It is just for me really, though. I don’t think anyone works with me because I have hardware. But, I definitely have a nicer workday.”

We ask Katie whether she thinks the creative aspects of mastering are often overlooked, by those who perhaps think of it as a purely technical process? “I think it can certainly be what people want it to be. If a band or an artist or a producer are up for letting go and having a proper collaboration. Sometimes producers will make limited reference masters – the mix with a limiter on – and sometimes the band have just listened to that so much that they don’t want it to sound any different. They want it to sound like that but slightly ‘something’ extra. That’s fine as well. Mastering is so much more than the audio processing part. It’s always nice when people are super open-minded about it.”

Katie tells us that ongoing dialogue with the track’s producer or mix engineer can be all too common: “From a mastering point of view, I’m looking for whether the mix functions. That’s what I’m looking at when I’m quality-checking a mix. Can I hear the vocals? Is the bass loud enough? Is there a hi-hat that is just blisteringly loud, and is the sibilance overwhelming? That’s what I’m listening for, the functionality of it. I’m never really talking to the mix engineers about creative stuff. I had one project last week where I felt the guitars were getting a little bit lost in the breakdown section, so that was a functional thing, it’s not necessarily a creative thing.”

Out of the jungle

We wonder how vital Katie’s new workspace is to how she listens and reacts to music? “So my [new] studio is in my flat – that was a choice. I’ve had studios in production room complexes before, which has been nice. I wanted somewhere where I could be super-relaxed and focussed. I don’t want people knocking on the door and kind of asking me to listen to stuff. It’s so nice and so important to be part of the community, but for me the headspace that I’m in when I’ve done my favourite masters is pure focus and pure enjoyment of the music. We all have days with interruptions and stuff, but if I can have as little as possible then that really helps my workflow.”

Tavini’s Brighton-based studio was entirely jungle-themed, something she admits started out as a joke that went too far… “I never want a studio that I work from to feel sterile; it has to be comfy. I’ve got a sofa in the back with loads of cushions. I need it to feel like a living room. I’ve got lamps everywhere. It needs to feel like somewhere where you’d listen to music. I’ve had day jobs, and they’ve always felt like work, I don’t want this to ever feel like work.

“I wanted to make my studio an environment where I look forward to being in the room every day. A review of my space from someone who came to visit the other day was ‘You’ve nailed the vibe’. There’s plants everywhere and art on the walls. This doesn’t have an overriding theme, aside from ‘living room’ and ‘calm’. It was really intentional to make this space like this.

“I don’t work well unless I feel like I’m completely immersed in the sound. I’ve had to occasionally do masters on headphones on my laptop. Even though they ultimately turned out well, I didn’t really enjoy the whole process because I think your surroundings matter. If I can make every single aspect of my mastering life feel really creative that’s definitely going to help. You can hear when artists are hugely passionate about their song, you can hear it in the performance and the way it’s delivered. You can’t recreate that love for it that they have but for everything that I work on I want them to hear that I love it by making it a little bubble of creativity, I guess.”

We ask Katie what advice she’d give to anyone thinking of pursuing mastering as a career route. Her advice: don’t wait around for opportunities, seize them! “You can download unmastered mixes from the web, so download some and have a go,” she advises. “Get fully immersed and don’t wait. Go to gigs, listen to loads of music, learn your headphones, learn your speakers and learn your room. Just get involved. If you’ve got friends who make music, then ask them if you can have a go at mastering their songs – even just for practising purposes. They don’t have to like it, but it’s really good if you can get actual feedback from real people who will offer it.”

“Mastering engineers are really friendly and we’re also generally pretty happy to answer questions. Dive in and have a go, and find mastering engineers that have worked on things you really like – email them and ask them about it. I think that’s so much better than going down YouTube rabbit holes and feeling rubbish about it, like you’re never going to have enough gear or it’s never going to happen.”

“No one from my family works in the music industry,” Katie says. “I didn’t have someone handing me work. I didn’t have someone teaching me, and I never had a mentor. I just knew what I had to do – and I had to go out and do it. Don’t wait for permission from anyone, just do it!”

For more information on Katie Tavini’s work and for details on how to work with her, head to her official website.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.