How to recreate classic synth sounds on hardware or softsynths

Eight tips to try in the studio

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From its inception, the synthesizer has been a forward-looking instrument; it was a tool specifically designed to generate new and unheard sounds. When the synthesizer was new, many people tried to copy the complex sounds of existing instruments, often seeking the comfortable sounds of the acoustic instruments they already knew. Today, however, people also want synths that emulate... synths as evidenced by modern “vintage” presets.

When Roger Manning Jr. and I made three albums as the Moog Cookbook in the mid-1990s, analogue synths were dead and inexpensive. We wanted to honour and bring back the original retro synth sounds that no one (at the time) was using. Many of those sounds were pure and simple, the results of musicians’ first synthesizer experiments. Luckily, the sounds gravitated toward the playable and the musical, so many of the older sounds are still noteworthy (sorry) today. Most of them have a sort of cartoon “funny” factor to them and conjure up disco and silly pop images, but they have character, and almost anyone can generate these sounds with an analogue synth, new or old, hard or soft. Recreate some popular classics with our step-by-step instructions.

Popcorn

This may be one of the most-dated synth sounds, as it was only popular for a short time, on one big instrumental hit. In 1972, the group Hot Butter arranged and recorded Gershon Kingsley’s great Popcorn and launched a Moog hit onto the charts. The sound used for the melody is onomatopeic, it creates a “popping” popcorn kernel sound like a percussive motif. This abbreviated minimal sound didn’t work for progressive rock, or even the ’80s synthpop crowd, so it remains an icon of expressionist synth programming circa ’72.

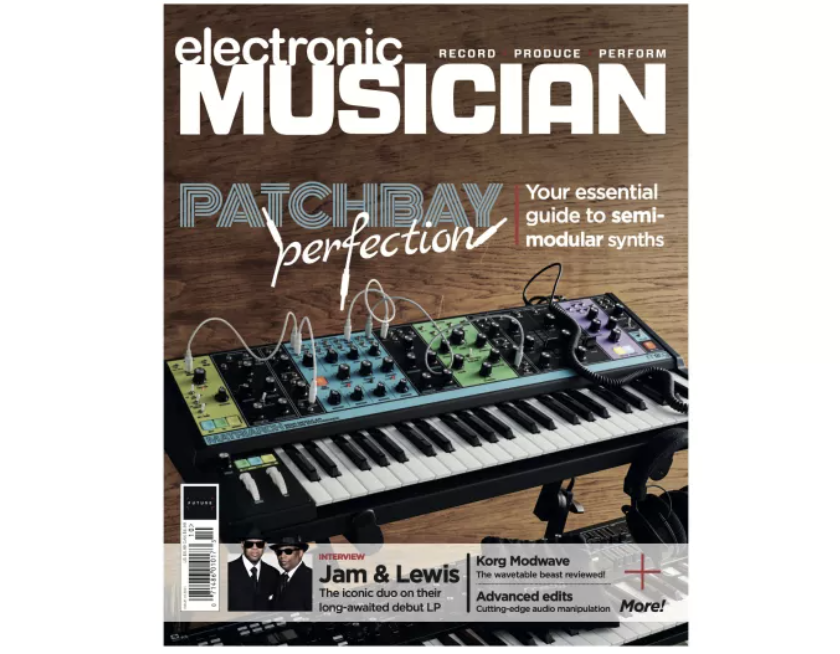

The 18 best synthesizers 2020: keyboards, modules and semi-modular synths

Once you hear it, just try to get it out of your head: the Popcorn sound. To create it, start with the purest wave possible, a square wave or sine wave; the hollow, round tone is what you’re after. Use a single oscillator, no need for stacking or multiple-tone fatness here. Don’t filter it; clean and bright is better. Run the oscillator through an amplifier section (most synths already do this) as controlled by an ADSR.

Can you believe we’re almost done? The trick of this patch is to set Attack, Sustain, and Release to zero; the only parameter you adjust is the Decay time setting. As you play, shorten the Decay until it reaches the minimum point where you still hear the pitch of the note. Too short and it becomes just a click or glitch; too long and it doesn’t 'pop'.

With the decay just right, you get a fiercely percussive note that has no staying power; it’s gone as soon as it happens. It’s perfect for... popcorn.

The dee dah patch

My college synthesis professor used to test everyone on patch-design with a version of this sound, and it is he who gave it the catchy name.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Start with a basic oscillator, it doesn’t matter which waveform or pitch, as long as you’re in a musical/audio range. (I use the term 'audio' here in reference to hearing range, to differentiate from the audible “clicking” an oscillator makes at frequency rates below that of human hearing.) Modulate the pitch/frequency of that oscillator with an LFO, set to square wave. I usually start with a slow range (maybe one oscillation per second), pushing the resulting note “high...low...high...low,” over and over. Tune the amount of modulation to an exact octave. Depending on your synth, this modulation may push the root note down as the upper tone rises (biased above and below your original note). If so, you’ll need to transpose or retune the original pitch so your desired note is on the bottom, alternating with a note an exact octave above it.

Now for the finishing touch: We want the LFO running pretty quickly so that the low-to-high oscillation is barely perceptible. Speed up the LFO to about 8 to 12 Hz, which will create a buzz of two almost-simultaneous pitches. It’s very melodic, and you can add some filtering or other changes to the waveforms. The dee dah patch is instant goofy space-rock. As a side benefit, it’s a sound that will cut through any mix, guaranteed!

The 'echo in space' arpeggio

This trick is partly in the sound, and partly in the performance. Start with a simple, pure oscillator sound, use a sine or square wave. The Envelope should be brief, with a shorter release; you want it tight and snappier on both the attack and release.

On the output of the synth (or internal effects), add a delay line with some feedback. Set the delay to approximately 300 ms or use a specific rhythmic value (such as an eighth note) if your delay system works with note rhythmic values. Add some feedback/regeneration on the delay until you hear about 6 or 8 repeats of the sound as it fades.

Play a quick arpeggio up a chord; the chord acts like a strumming effect, which can add a strong emphasis point on a chord change or sectional change in a song. And the delays add that classic spacey vibe. Single notes can also add a little spice to an arrangement.

Sample-and-hold filter patch

This is one of my favourites. You’ll hear it now and then in a Tomita track or something from Perrey and Kingsley. However, the synthesizer needs a few key elements to make this work, and not all instruments have these features. First of all, you need a sample-and-sold circuit, fed by a noise source or random input. The sample-and-Hold needs to trigger with a key-on command, sampling a new level whenever a key is pressed.

Perrey and Kingsley helped make the Sample-and-Hold patch famous. If you have these options, configure them so any keypress triggers a new random value from the Sample-and-Hold circuit. Assign the sample-and-hold output to a lowpass filter, and adjust so that it only changes the filter setting in a middle range, not too high or low to be clearly audible. With a little resonance added to the filter, each note will have a random timbre, some bright, some dark. It’s very musical and entertaining to hear. It’s a shame that some instruments don’t offer per-note control of the Sample/Hold circuit; you can approximate this sound with a repeating clocked Sample/Hold, but it gets very regimented and won’t follow the melody and rhythm that you’re playing.

1960s computer sound

This sound is about as basic as it gets, but the effect is strong; just play it and watch people’s reactions. Invariably, people think, “this is what computers sounded like in the 1970s.” Not really, but computers were portrayed this way in film and TV, using this simple patch to simulate calculation in action.

Take any sound, preferably something rather steady and uniform, such as a simple oscillator or two in unison. No vibrato, no waveform motion; the more pure and simple the tone, the better the outcome. Remember, computers tend to be stiff and cold, not vibrant and warm.

Control the pitch with wide-ranging sample-and-hold randomness; this can be spread across several octaves. Set the sample-and-Hold timing to about 125 ms (8 times/sec). Playing and holding one note is all it takes: a random pitch played with a single key; it’s almost the stereotypical demo of a sample-and-hold effect. Your audience will be transported back to the world of Commodore 64s, Apple II, and the TRS80.

The "sad" sound

I read a record review once that said that synthesizer sounds are inherently sad. It’s not necessarily true, but it’s an interesting idea; composers can lean that way with this simple program.

You’ll need a synthesizer that allows an envelope generator to control pitch. If you have that, the rest should be easy. Start with a dark, almost dull sound. Any waveform will do, but make sure brightness is filtered out. Route the envelope into the frequency/pitch of the oscillators, and set the Attack time fairly short, but not immediate. You’ll need a small “glide up” to each note you hit. Sad, indeed.

The whistler

This next one is another classic from the turn-of-the-’70s synth boom. The sharp emphasis of a resonant lowpass filter makes this possible.

Feed a noise source into the lowpass filter. Increase the feedback/resonance of the filter until it oscillates, then back it off just a little, just before it howls on its own.

An unfiltered noise spectrum is quite wide, covering many octaves. Such a spectrum doesn’t sound very musical when filled with noise, but the resonant filter cuts out frequencies beyond a selected cutoff point and emphasizes a narrow group of frequencies right at that cutoff. This configuration gives us a fairly good whistle effect, as we’ll hear not only our desired “note,” but also a few rough pitches, sounding like noise, surrounding that note.

This patch opens the door to a whole new world of synthesis tricks. It does require a function that not all synths offer: You must be able to modulate the lowpass filter with an audio-rate wave. Many classic synths (Minimoog, ARP 2600, etc) allow this configuration, but many do not; the fastest some synths can move the filter is with a fairly slow (5 times/second) LFO. Many newer software and hardware synths often offer this setup, or feature an LFO that can be run in the audible range.

Start with a basic patch, from one to three oscillators playing in unison. Any waveform and pitch will do, but try starting with bass ranges to make this trick more obvious while you learn to control it. Feed the sound of these oscillators through the lowpass filter, and add some feedback/resonance to the filter until it gets a significant “wow” sound when you move it by hand.

The next step is key: Modulate the filter cutoff point up and down with an audio waveform. On synths such as the Minimoog Voyager, ARP 2600/Odyssey, Pro-One, or Prophet 12, you can use any oscillator that follows the keyboard in pitch.

Ideally, you want the modulating oscillator(s) to be two or three octaves above the pitch of the note you are playing. Adjust the modulation and the filter settings across their ranges: When you reach the ideal state, the filter will respond with a very clear vocal effect; you should hear a talking sound as the filter is slowly moved up and down (by hand or via an ADSR). In essence, you’ve created some fairly complex vocal formants as the filter moves up and down very fast. This process emphasizes certain parts of the spectrum, and it will sound as if the synth was being processed through a talkbox or vocoder.

Modulation in the audible range is a simple step that opens up a huge world of complex synthesis; you can use FM to create new spectra of sound from simple oscillators, get bizarre and luscious effects from normal filters, and pull spacey ring-mod effects from VCA stages. Once you realise the variations that these techniques impart, your synthesizer becomes a complex beast.

Electronic Musician magazine is the ultimate resource for musicians who want to make better music, in the studio or onstage. In each and every issue it surveys all aspects of music production - performance, recording, and technology, from studio to stage and offers product news and reviews on the latest equipment and services. Plus, get in-depth tips & techniques, gear reviews, and insights from today’s top artists!