How to record drum tracks in a small room: part 1

Got a small recording space? Fear not: Even with no room to swing a cat, you can easily record drum tracks that sound huge

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Got a small recording space? Fear not: Even with no room to swing a cat, you can easily record drum tracks that sound huge. In this first instalment of a three-part series, we’ll offer some tried and tested tips for recording bang-up trap drums in pint-sized digs.

Set a trap

Choose a room with a good bass-frequency response to record the kit. Rectangular rooms offer a more even bottom end than square-shaped ones. Avoid perfect cubes (where the length, width, and height of the room are exactly the same dimensions) if, at all possible, they are the worst for recording drums (or anything else, for that matter). If you can, set the kit up on a hard surface instead of on carpet. Wood, cork, bamboo, tile, concrete, and even vinyl flooring will make your drums sound much more lively than a carpeted floor. Treat any opposing walls (and the ceiling, if it’s a consistent height above a hard floor) with acoustic materials as needed to tame flutter echoes.

Get high and mighty

The most important thing you can do to assure great-sounding drum tracks is to raise the crash and ride cymbals as high as possible without compromising the drummer’s ability to play well. If you were to set the cymbals too low, they would bleed so loudly into the tom mics that it would be virtually impossible to shape the sound of the toms independently of the cymbals during mixdown. You wouldn’t be able to make the tom tracks sufficiently loud without the cymbals overwhelming the mix. And goosing high frequencies on a rack-tom mic to bring out the thwack of stick hits would also make crash and ride hits cut like razor blades across the ear drums. Get those cymbals up!

If possible, have the drummer rack the floor tom before the session. It will produce much deeper and longer sustain when racked compared to when sitting on legs.

Go on a microphone binge

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

There are two basic approaches to recording trap drums. One method uses a pair of somewhat-distant mics to capture the entire kit and then reinforces the kick and snare drums as needed with a close mic or two. While this strategy produces an organic sound that works well for traditional styles of music, it often won’t give you the control, flexibility, and focus you need to fashion explosive drum tracks that rock. And an over-reliance on ambient mics in a small room, especially one with sub-optimal acoustics is a recipe for weak and washy-sounding drum tracks.

A better approach is to place a separate close mic on each and every trap drum. Additional overhead and ambient mics are used to record the cymbals and the overall sound of the kit in the room. Each mic signal gets recorded to a separate track on your multitrack recorder or DAW.

This binge-micing setup dramatically increases your options later in the game. You can adjust the level, EQ, panning, envelope shape, and dynamic range of each trap drum virtually independently of the others during mixdown. Overhead and ambient mics can be goosed or lowered in the mix without dramatically changing the levels of the traps. Discrete drum tracks that sound weak can be bolstered or replaced by samples using plug-ins such as Slate Digital Trigger and WaveMachine Labs Drumagog.

Know your enemies

Using a lot of mics to record drums has two major drawbacks if done improperly: It can cause phase cancellations and degrade stereo imaging.

Let’s examine phase cancellations first. When the sound of the kick drum, for example, arrives at both its intended mic and the mic for one of the toms, the two signals will be out-of-phase with one another and cause certain frequencies to become attenuated. For reasons too complex to explain here, the most audible penalty is weakened bass frequencies. Bottom line: Multiple mics placed willy-nilly on a drum kit can make the traps, in particular, sound weak and thin.

The same combination of intended and unintended mic signals can also cause stereo imaging to degenerate. If the recorded kick is panned dead-centre but kick hits also bled into the mic for the floor tom, panning the floor tom anywhere but dead-centre will pull the image of the kick drum off toward the side of the stereo field. Poor stereo imaging makes drums sound washy.

In part two of this series, we’ll show you how to place each mic on the traps to minimise both phase and imaging problems. You’ll learn how to produce punchy drum sounds that have laser-like focus and clarity.

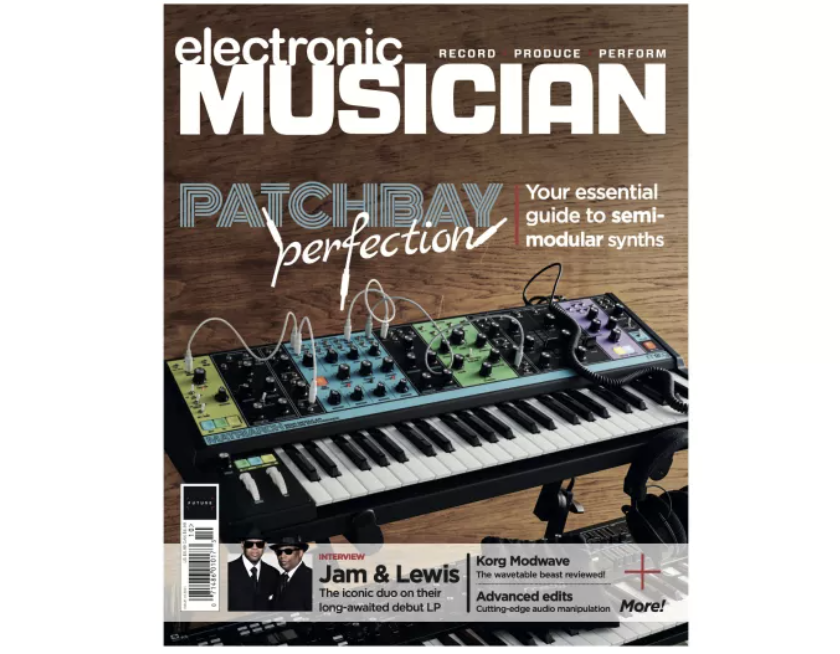

Electronic Musician magazine is the ultimate resource for musicians who want to make better music, in the studio or onstage. In each and every issue it surveys all aspects of music production - performance, recording, and technology, from studio to stage and offers product news and reviews on the latest equipment and services. Plus, get in-depth tips & techniques, gear reviews, and insights from today’s top artists!