Classic interview: Oneohtrix Point Never - "For me a synthesizer is an abstract tool; I look at it and I'm just guessing a lot of the time"

We revisit a 2015 chat with The Weeknd collaborator Daniel Lopatin

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Currently in the spotlight thanks to his writing and production work on The Weeknd's critically-acclaimed album Dawn FM, we spoke to Oneohtrix Point Never - AKA Daniel Lopatin - back in 2015, as he was releasing his second album for Warp Records, Garden Of Delete.

Since then, Lopatin's career has gone from strength to strength. He's released two more studio albums, composed highly-rated soundtracks (Good Time, Uncut Gems) and produced not only for The Weeknd - both on Dawn FM and previous album After Hours - but also FKA Twigs.

Let's go back to a time before all that, though, and find out how Lopatin got his start.

Not many people are lucky enough to have a dad who owns a Roland Juno-60. For Daniel Lopatin, it opened a portal into the world of electronic synthesis, his labyrinth of electronic musings emerging under the moniker Oneohtrix Point Never - a play on the frequency of his favourite Boston radio station, WMJX.

In 2010, Lopatin released Chuck Person's Eccojams Vol. 1, widely credited as a precursor to the esoteric vaporwave genre. In the meantime, the producer's Oneohtrix Point Never project was signed to Indie label Editions Mego, spawning acclaimed albums Returnal and the following year's Replica on his own Software label.

However, Warp Records was always a natural fit for Lopatin's morphogenetic experiments. The label released R Plus Seven (2013) and leveraged live support for Nine Inch Nails, opening for grunge rockers Soundgarden.

Meanwhile, Lopatin's claustrophobic landscapes were deemed soundtrack-eligible for Sofia Coppola (The Bling Ring) and Ariel Kleiman (Partisan).

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

With new album Garden of Delete, Lopatin plunges the audience into another cryptic, fictional universe. We caught up with him in his studio to find out all about it and, indeed, him.

Untypically, it was your father's love of jazz that lead you to electronic music…

"Yeah, because I grew up listening to my dad's fusion tapes and loved the keyboard work so much. When you're 10 or 11, it sounds like aliens talking to each other. And because he was in some bands, he had a Roland Juno-60 plugged into this Peavey 120-watt bass amp, so he'd let me mess around with that."

We understand the Juno-60 was also one of the first instruments you bought.

"That's true, because it's easy and straightforward. It's an analogue synth with some digital controls and a great arpeggiator, which was a big treat for me as a kid. I took the Juno with me to college and was using it in this high school band with my buddies.

"I was actually in a grunge band in middle school and got kicked out because I auditioned 'to play bass', which I didn't have - I could only borrow it if I passed the audition. As soon as he saw me hold the bass, I was fired."

Did you try to convince them to use the Juno or just take your own path?

"Well, years later when they were transitioning to be a jazz/funk quintet, they were like, 'Hey, we need a keyboard player', so I brought my dad's synth over. At that time, I was listening to Herbie Hancock's Sextant and Thrust, but also this show called Tape Deck Tuesdays on college radio in Boston, and listening to a lot of hip-hop.

"Eventually I got a Goldie double CD with a crazy mix he made and my curiosity about linking instruments up together and sequencing them finally piqued. I got my hands on a very simple DCB sequencer for the Juno but realised it was totally shit, so I replaced it with MIDI and then Cubase - then I started messing around with software. It's probably a pretty typical story for someone getting into electronic music."

Garden of Delete almost defies categorisation - is that intentional to keep the listener guessing?

"It's funny, because in my head when I'm making these things - and I realise that there's not a lot of objectivity when you're trying to make a record and think about what it is you're doing - I thought I was making my version of a rock record. It's the most direct stuff that I could make, although I completely understand that it's maze-like.

"The way I work is second nature to me, so I'm not totally cognitive of how confusing or insane it sounds. I like that and think it adds something to the overall experience of the songs, but I do think of them as abstract rock tracks.

"I'm still figuring out my way of doing things incrementally. Going back to Returnal, every record gets a bit surer of itself in terms of songwriting. That's why I was able to do the MIDI thing, because there were very clear riffs and progressions."

Do you mean the MIDI files you uploaded to the Kaoss Edge website prior to the album's release?

"I was so bored with the typical cycle of premiering one song, then the second song, and then there's a video or another gimmick and another gimmick after that. What if I gave these MIDI files out that just have the riffs for the main progressions from a bunch of songs on the album, so the first thing that people hear is a preview of the melodies, but they can skin it themselves and do whatever they want with it? I thought that was a more interesting and less played-out way of going about sharing music."

And in effect, people can create remixes or different versions of your tracks?

"Yeah, because what I didn't really anticipate was that most people were taking the MIDI verbatim, which is cool. I hadn't listened to the files before I dumped them on the internet. They're really kind of unpolished, because there were all these MIDI instrument chains on them and further processing once they were audio. So a lot of the stuff you're hearing in the raw MIDI is weird because of the way the arpeggiator was timing. To hear the files without all these bells and whistles was bizarre.

"So, yeah, to answer your question, I gave out an email address and I'm trying to keep track of all the mixes and create a repository, because the people that are making them are usually my fans and I think it's a nice way to acknowledge them."

"I remember we were listening to Lithium and Ozzy's Boneyard and all this ridiculous rock stuff, and kind of getting into it and letting it seep in."

There's a surprising amount of guitar on the album and it's used quite aggressively. Why bring that element into a normally very electronic sound?

"I think that it was circumstantial. I went on this tour with Nine Inch Nails and Soundgarden. I was actually opening for Soundgarden, technically, and playing to their audience, which is not really mine; it's kind of like a tap-out bro audience.

"So I was driving to these amphitheatres to make the 5:30 soundcheck with my friend, and we had the satellite radio on but could only find music that was appropriate for this bizarre situation we found ourselves in. I remember we were listening to Lithium and Ozzy's Boneyard and all this ridiculous rock stuff, and kind of getting into it and letting it seep in. When I got off tour and got back to the studio it just felt like a natural thing to do."

Did supporting Nine Inch Nails show you a different side of the industry to the insular activity of making music on your own?

"100 percent, because it was a huge Live Nation tour. Unless I'm at a festival gig, I'm usually playing to audiences of 300 people in Brussels or 800 in LA. So going from that to an amphitheatre show, where I was playing to a Soundgarden audience who were really antagonistic, was very different.

"I talked to Trent [Reznor] and got his blessing to do a pretty aggressive drone set, which was more similar to the music I was playing when I had five people in the audience, but I somehow felt that was going to go down better for me."

How did it turn out?

"I only had about 20 minutes, so I made three very epic drum-based pieces. I'd gone on a similar tour in terms of scale with Sigur Rós and done my normal set, but it didn't really pop off, so with this one, I was like, 'How do I get them to remember'? I mean you have to entertain people, and you have to entertain yourself, so if they're not really going to understand the normal thing I do then let's at least leave this intense memory of a noise set."

There are few beats underpinning your music, almost as if the rug has been pulled from under you…

"This one actually has more syncopation than any of the others, but that's probably telling of how little drums there are on most of my records. I don't like straightforward drum sounds and hate snares; can't stand them.

"While I absolutely love a great drummer and get tunnel vision listening to drums at a show, a lot of the time I feel like drum machine-driven music tethers you to a genre. Drums really drive the style of electronic music, so you end up being like, 'Oh no, I'm in drum 'n' bass world or grime world', and I've never been comfortable enough to make a choice or commitment.

"I find that when there's no drums and you have to find other ways to make syncopation, it adds this alienation to the place where I want to be - a musical world that I feel like I could actually belong to."

Is the album an interplanetary tale or is that my perception?

"I like that, let's roll with it. I think the concept for this record was really memories of my puberty, because I don't have very clear ones so I started making a lot of shit up.

"The other aspect of that is that you tend to remember the most traumatic things. The most exciting moments are the most traumatising moments - or it seems like they're the only ones that survive. So when I was looking back, all that was left was the trauma, so it felt like making a really dark record was appropriate."

Is your music an interpretation of the visual ideas swimming around in your head?

"Yeah, a lot of the time I'm taking these inputs and asking myself how I can characterise that in musical form. And they don't necessarily have to be objects or places or landscapes; they can just be ideas, like ideas about rock.

"With some of them, it's like I'm trying to be as close to a sculptor as I can be, as opposed to being a musician. I'm trying to create these abstract forms that might be suggestive of the influences and inputs I'm getting."

But not deliberating that?

"Yeah, it's vague. I'm not so super-analytical about it, but I definitely like to think about the choices I make and try to think of these things as weird little sculptures.

"The last record was probably more explicit in that way. I thought of that as a really domestic record, because I made it at home and it was like a bachelor pad before my girlfriend moved in, but she made it really peaceful and beautiful. I was spending a lot of time with her, so to me it's a record of interiors, like a bouquet of flowers or a tableau of some sort.

"Any more of that, though, and I would have repeated myself, so this album was totally done in a dungeon studio - a basement B editing room that I had at the very bottom corner of this building. I'd take the bus there and spend 12-15 hours in it. There were no windows, so you'd lose track of time, and all of these bratty, adolescent impulses come out in a space like that."

Listening to your music is like being attacked from all directions. Would surround sound be a good fit?

"Yes. What we did for [2013 album] R Plus 7 was an event where we did a multichannel version of the record in a circular dome space.

"A surround version would be awesome for this record. I listened to Talking Head's Remain in Light recently… a five-channel surround version that they'd recently done in a studio in LA that could actually replicate it really well, and I was like, 'Damn, this does so much for drums'. I love hearing percussion behind me, it just feels like you're at a show or whatever, and I'd love to do that, so if anybody wants to be a patron of such an event…"

Is your setup software-based or a mix of gear?

"There's some hardware, but from an instruments point of view, most of it was software on this record. But yeah, I have a couple of preamps just to get the outboard synths sounding better going in. I've got a great reverb pre and a UAD with a nice blend that helps me calibrate the sound if I want things to be a bit more even and aggressive, or more tubed-out and variable."

What hardware synths are you using at the moment?

"I have the Juno-60 that I mentioned, an Alesis Andromeda, which is very popular these days. Everybody's putting out analogue synths again and the Andromeda is a late '90s synth but all analogue. It's probably somewhat anachronistic today because there's so much around like it now, but I love how it sounds.

"I have a Waldorf Microwave XTC that I worship and control with a software editor called Monstrum XT that allows me to randomise its parameters, as I'm not very good at programming synths. I've also got an Elektron Analog Four, but the rest of the stuff's been decommissioned. If I'm not using something, I tend to sell it and move on, so I'm not too sentimental about hardware synths."

"If I'm not using something, I tend to sell it and move on, so I'm not too sentimental about hardware synths."

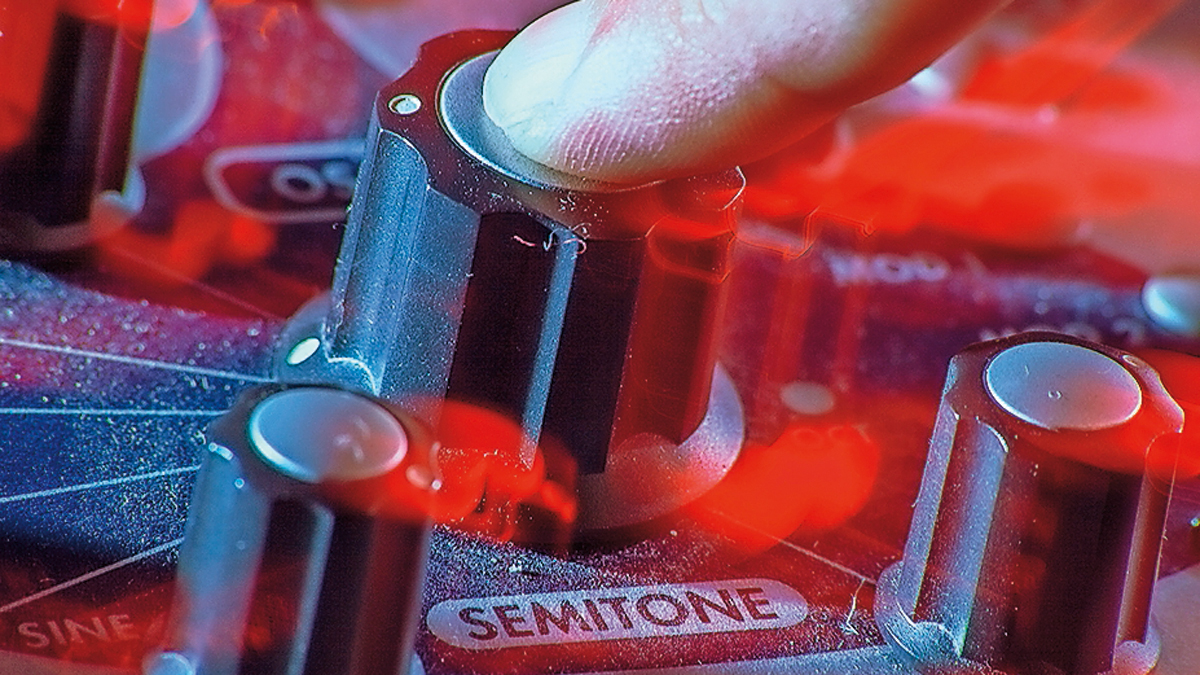

In terms of sound creation, does using hardware appeal to you as much as software?

"I do think there is something to be said for rolling tape, working through some ideas and recording a crazy knob-twiddling session. Especially if you chop that stuff up; it usually turns out pretty great.

"I find that when I sit down at Ableton and start automating a lot of those things, I'm approaching it with a little bit too much purpose and premeditation, and tend to draw these straight lines; it just lends itself to being a little bit more analytical about how you want things to change over time.

"Some people know what they're doing, but for me a synthesiser is an abstract tool; I look at it and I'm just guessing a lot of the time, so that helps me to get my fingers on it. The ideas are clumsier, although they are the better ideas sometimes."

You moved to Ableton Live from Cubase, right?

"Cubase was a pretty short-lived love affair. I had a good handle on Pro Tools before Ableton, but it seemed to me to be no longer necessary.

"If I'm producing somebody's record and there's a need for more architecture or a band to come in and do that kind of recording, I would never use Ableton.

"The other thing that I dislike about it is the way it sums everything down to stereo if I just want to make a direct bounce. I don't generally like how that sounds.

"So there's a stop with Ableton as I really don't want it to be the final location for a bounce. Everything up until that moment, I'm sold - love it; but I try to get it broken out and sound a different way at another studio, usually with Pro Tools."

What plugin instruments and effects do you find yourself turning to most frequently?

"I love [u-he] Zebra and used it extensively on this record. I love this company, Plogue, who made a speech synthesizer called Chipspeech that I used for all the vocals. I love Ableton's vocoder and Operator for basic side subs and general low-end.

"There's this really quirky, fucked up one I like to use that's made by a company called Humanoid Sound Systems, called Enzyme, which is super-aggressive and industrial-as-fuck; it can't help but sound like NIN Broken-era stuff. It's the only thing it can do and it's got a big fat random button on it, which is great for me.

"I like a lot of iZotope stuff for processing. Their EQs are great, but their spectral sampling synth, Iris, is really good too, so props to them for that. I use Spectrasonics Trilian a lot for the Chapman Stick-style stuff, and on the previous record I used Omnisphere a lot for choir sounds, but that's not news - everybody knows that."

We get the impression you love that side of production, searching out plugins that can do weird and wonderful things?

"I'm obsessed; I, like, troll Richard Devine's Instagram. Okay, I guess I lurk it, I don't troll - I respect the guy a lot. I would recommend to anybody that wants to keep up with stuff, you have to follow Richard Devine's Twitter and look at his Instagram, because he's pretty much constantly beta-testing everything and anything; he's a good filter for that stuff.

"I look for something that's really easy to use, something that allows me to quickly alter or destroy what I'm working on and flip or toggle the sound really quick without relying on presets. Randomisation is always something I get excited about when I'm looking for a new VST."

One of the maxims on your studio wall was 'Do More With Less'. Is that still how you look at things?

"Yeah, because I tended to be hoarding a lot of software, like Reaktor instruments and stuff, but the more I think about it, if you hear something you like, just work with it, don't overthink stuff or wait for the perfect software, because you're wasting your time. Your brain is going to be the most important software that you have… or I guess hardware - unclear at the moment [laughs].

"Don't worry too much about the gear and remember that your brain is going to be the thing that allows you to do the most with those tools. And also, if you like something about a sound but not everything, work destructively and think about twisting things up when they're audio. Don't always think synthesis is the be all and end all for sculpting stuff. I think audio is where it's at for me, because once it's audio I can really start twisting it into its final form."

How do you translate your music to a live setting?

"A lot of it is going to be about dubbing out and remixing the record, so there's a certain amount of playback involved in that.

"I usually make two versions of every album; one is the record I make and the other is the one for the live setting, and that involves a lot of reduction and making a knucklehead version of everything, taking out all the details and thinking, 'What's the point here? Well, it's this riff'.

"OK, so it's a syncopated series of samples; take everything else out and take it down to its basic component parts and that will give you plenty of space to add things live that are in the moment."

What gear will you typically use to create the conditions for an improvisational set?

"It will usually be Ableton with a couple of controllers and various pieces of software, where I have the main parameters set up so there's a logical flow on those two controllers. Then I'll use a 16-track mixer where all of that stuff gets broken out.

"I tend to do more specific types of manipulation on the MIDI controllers, rather than dubbed-out Lee Scratch Perry-type tomfoolery on the mixer, with some Eventide stuff dealing with the big cloud-level environmental effects. The computational stuff is happening more on a micro level… little sounds in the box."

How interested are you in bringing the music to life in a visual format?

"I work with this guy, Nate Boyce, who's a sculptor. He also does the most insane video art ever. He's incredible, so I let him decide that stuff. He's also a musician and we're best friends, so he knows my stuff inside out and I usually give him carte blanche to express himself.

"What we're going to try and do for this upcoming tour is have two giant flat-screen TVs vertically aligned with a lot of stuff that wouldn't make sense in landscape view - so more text, language and symbol-type stuff. And then a projection behind us that's landscape-oriented and puts you in an environment… and hopefully a shit ton of dry ice - that should do the trick [laughs]."

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.