Yamaha Reface synths reviewed!

We check out Yamaha's Reface series

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the 50 years since Yamaha entered the electronic keyboard market, they’ve rocked the industry many times over. In 1966, they kicked it off with a series of transistor organs. In the ’70s, they released the CP series of electro-acoustic pianos and the CS-80, a programmable analog polysynth that’s coveted and imitated to this day. In the ’80s, they unleashed the DX7, which changed the sound of all music from that decade virtually overnight. When the Reface teaser videos—which referenced all these instruments—appeared in the days leading up to Summer NAMM, the synth world was abuzz. Let’s see what all that buzz is about.

Different and Common Features

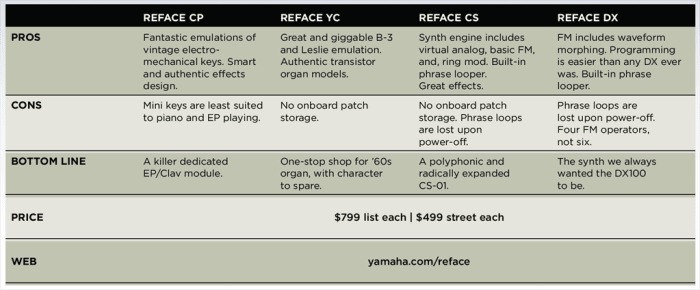

Each Reface keyboard addresses a different aspect of Yamaha’s history. The Reface CS is virtual analog. The Reface DX refreshes their approach to FM. The Reface CP focuses on electric pianos. The Reface YC captures the sound of both tonewheel and transistor organs. With each sporting a street price of around $500, they’re affordable enough that you can pick and choose one or more that best suits your musical style.

All four sport velocity-sensitive mini keys, the option to run on six AA batteries, and built-in speakers, making them compact and ultra-portable. They’ve taken some online bashing over the mini keys we can understand any keyboard player wishing for full-sized keys—especially on the CP and YC. Think of the Refaces as purpose-built synth modules that happen to have “courtesy” keyboards and speakers for mobile use; on that note, we’ve never heard anyone criticize a Waldorf Pulse 2 or Streichfett for having no keys at all. Plus, since they support old-school MIDI as well as USB, you can play any Reface from the controller of your choice.

Since each Reface is its own little universe, we’ll devote separate mini-reviews to them.

Reface CP

With its focus squarely on electro-mechanical keyboards, the Reface CP is suitably nostalgic, sporting retro knobs and silver toggles that add a touch of that ’70s and ’80s-era Radio Shack magic. The CP’s operation is blissfully straightforward, combining great sounding electric pianos and a Clavinet to round things out, with effects that are perfectly suited to recreating the classic sounds tricks of keyboards from that era.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Sounds. The core Reface CP sound is based on six presets: Rhodes Mk. 1 and Mk. 2, Wurlitzer EP, Clavinet, Yamaha CP-80 electric grand, and a lovely toy piano as a bonus.

Of the two Rhodes, I was always partial to the Mk. 1 because of its rounded warmth. The CP’s version does not disappoint, recapturing that sound beautifully and immediately evoking some of my favorite Steely Dan hits. The Mk. 2 preset also nails the character of that iteration, with its emphasis on the tines. The Wurly had me jamming out old Queen and Supertramp classics with glee.

As for the CP-80, its metallic sheen and muted bass notes nail the sound of Peter Gabriel and Simple Minds alike. The Clavinet is particularly satisfying, with high playing velocities delivering that funky spank.

Yamaha tells us that these instruments are sourced from their CP4 Stage (reviewed Jan. ’14), and they certainly sound like it—which is to say, their quality and authenticity is what you’d expect from a high-end stage piano, though of course that keyboard has more variations on each sound type.

Effects.The five effects are in series: Overdrive into a tremolo/wah unit followed by a chorus/phaser, then a delay followed by a reverb.

The Overdrive knob behavior depends on the selected preset, with the electric pianos receiving gentle grit and warmth, but the Clavinet getting downright crunchy with that guitar-like sound at maximum settings. With the toy piano sound, the knob works almost like a mic emulator that also includes a touch of room sound. On the CP-80 it’s extremely subtle—almost like a tone knob for the pickups.

The next effect can serve as either a tremolo or touch wah. Flavors of tremolo are tied to the preset: The Wurly, toy piano, and Clav modulation is a non-panning triangle/sine wave, whereas the Rhodes models pan in stereo, with an immediately recognizable square-ish wave. The CP-80 has a triangular feel, but also in stereo. The touch wah behaves predictably across all six presets, and delivers that “Higher Ground” wah sound on the Clav.

The phaser/chorus section is another either-or proposition, but that’s fine since adding both to an instrument tends to make things muddy. Here the chorus has a real richness with a lot of stereo width. The phaser is also gorgeous when paired with certain pianos, notably the Rhodes Mk. 1 for that trademark Steely Dan sound.

The Delay is cleverly implemented and can be switched to either analog or digital mode. In analog mode, the repeats have a decidedly tape-like character that sounds fantastic in every way. The digital mode is clear and pristine, as expected, with a much wider range of delay times.

At the end of the chain is reverb, with a single knob for depth control. While its personality doesn’t change in the context of different presets, it’s rich, spacious, and wide, with a smidgen of animation.

Conclusions. I was blown away by the attention to detail in both the Reface CP’s instruments and effects. So much so, that the tiny keys were really the only thing that became irksome over the course of my testing. Considered as a portable MIDI sound module, it’s genuinely impressive. Played from a more substantial controller, it’s even breathtaking.

Reface CS

Anyone who remembers Yamaha’s original CS-01 mini synth will smile at its apparent reincarnation here, which isn’t that far off the mark. Both can be battery powered (, include speakers, and offer familiar analog controls—but this is 2015 and that’s where the similarities end, as the eight-note polyphonic Reface CS also nods at the massive sound of the monster CS-80 analog polysynth.

Synthesis. The Reface CS’ sonic range belies its simple front panel, making it nearly impossible to come up with a bad sound. That’s not to say that it’s incapable of sonic complexity, but the way it’s all implemented makes experimentation fun regardless of your synthesis skill level.

The architecture draws from the original CS-01 in many respects. An oscillator feeds a resonant lowpass filter, with a single LFO and envelope for modulation. What’s interesting is how Yamaha has brought this design into the 21st century.

For example, the oscillator section is actually a five-mode tone generator that’s capable of an impressive array of sounds, thanks to a pair of “macro” sliders—Texture and Mod—that shape each mode’s character in useful ways.

Multi-Saw mode delivers EDM-friendly chord and lead sounds, with the Mod slider controlling the detuning amount and Texture adding a sub-oscillator. In Pulse mode, Mod controls the pulse width while Texture tunes a second pulse wave in semitone increments. In Oscillator Sync mode, the two sliders control sync tuning and envelope modulation depth, for recreating those vintage swept leads. The Ring Modulation mode, which offers a taste of some of the more aggressive textures of the CS-80, with the two sliders controlling the pitch of each of two oscillators for nasty, clangorous tones. Rounding out the options is a basic FM mode, with the sliders governing FM envelope amount and the tuning of the modulating oscillator. I was really impressed with all of the modes and was able to sculpt both traditional and exotic flavors quite easily, thanks to the twin macros.

The lowpass filter is based on an 18dB-per-octave slope, which is both a nice compromise between 12dB and 24dB, and incidentally the same slope as the original Roland TB-303. That’s not to say it’s a dirty “acid” filter, though the resonance’s squeaky self-oscillation can emulate that sound in a pinch. Keyboard tracking is always on by default, a sensible decision. I was also able to coax out pseudo-organ sounds by setting the resonance to 90 percent and tuning the cutoff to an octave plus a fifth. All in all, it’s a nice sounding virtualization with negligible compromises.

Surprisingly, the CS doesn’t have onboard preset memory. That will be the job of Yamaha’s implementation of WebMIDI. A planned website called Soundmondo will provide for “social sharing” of voices across the Reface ecosystem. More locally, an iOS app called Reface Capture will let you manage Voices (sound presets) and even set lists, handshaking with your Reface model(s) upon connection.

Modulation and effects. For modulation, the LFO is a simple triangle-wave only affair that can be routed to either the oscillator’s tone character, overall pitch, filter cutoff, or amp—but not multiple destinations at once, which isn’t that big a deal in the context of such a streamlined instrument. The envelope section is a standard ADSR with an interesting twist: A slider morphs its destination between the amp and filter, allowing for some subtle enveloping tricks that give the design a tad more sonic range.

At the end of the chain is a single effects unit that can operate as either a delay (with lovely tape-style feedback), a really sweet phaser, a combination chorus/flanger, or a decent overdrive. A pair of rate and depth sliders offer a touch of customization.

Phrase looper. The phrase looper is an onboard free-running unquantized MIDI sequencer that can record up to 2,000 note events, then play them back with the ability to overdub new parts on top and tweak parameters in real time as the loop cycles.

This is handy for impromptu jam sessions or recording your improvisations, sketchpad-style. Unfortunately, there’s no way to offload these sketches to your computer via USB, so if you accidentally write the next Taylor Swift hit while you’re doodling around, you’ll have to record the resulting sequence as audio to your DAW (aided by the fact that the CS does sync to external MIDI tempo) before powering down.

Conclusions. For such a compact synth, the Reface CS is a surprisingly capable little beast. While some users may be put off by the lack of presets, the synthesis engine is so intelligently implemented that it just might help newcomers learn the essentials without bumping into the walls too much. Good stuff.

Reface DX

While Yamaha’s six-operator DX7 synth was the game-changer of ’80s pop, the four-operator DX9 and its offshoots such the TX-81Z, DX11, and DX-100 were more affordable and portable. The Reface design artfully recaptures this. With so many four-operator FM synths hitting in the same decade, their sound became a mainstay of the then-nascent dance music scene. Tracks like Orbital’s “Halcyon and On” were grounded by the DX-100’s “Solid Bass” preset, and that’s just one example out of thousands. Currently, the “future house” craze is based heavily on FM synthesis. So, whether you’re looking for a modern sound or feeling nostalgic for the ’80s, the Reface DX is a treasure trove of sonic inspiration.

Architecture and Sounds.Of the four Reface synths, the DX is the only one with patch memory: 32 overwritable presets. Because of the intricate nature of FM synthesis, this is an absolute necessity. That said, it’s worth mentioning that even Yamaha’s 30-year-old DX100 offered 192 presets, so 32 seems a bit skimpy, especially in light of the sonic versatility.

On the plus side, Yamaha has skillfully curated those presets. On the vintage side are timeless patches like the FM “Rhodes” that underpinned hundreds of ballads. Another highlight is a spot-on recreation of the “Tubular Bell” preset that will either remind you of Paul Hardcastle’s “Nineteen” or Taco Bell commercials from the ’90s. Another standout is the “Attack Bass” patch, which instantly evokes Howard Jones’ “What Is Love?” At the modern end, “Feel It” and “Wobble Bass” are candidates for future house and dubstep, respectively.

While an FM synthesis tutorial is outside our scope here, if you’re familiar with the territory, the Reface engine offers some clever new amenities that push the technology a bit further. What’s more, the Reface DX’s backlit LCD screen makes programming sounds directly on the synth much easier, thanks to its graphical envelopes and algorithms. Additionally, the user interface allows access to four parameters simultaneously, each with its own context-sensitive touch fader that can be “flicked” for rapid parameter adjustments.

There are 12 preset FM algorithms, which are more than enough to cover all but the most intricate design maneuvers. Each operator includes its own envelope, each of which is a four-stage rate/level affair like on the DX7, as opposed to the simpler envelopes of the TX-81Z and DX-100. The dedicated pitch envelope also follows this model, allowing for wild digital swoops when applied to just one or two of the operators (instead of all four). A single mutli-wave LFO can be routed to the pitch or amplitude of each of the operators discretely, allowing for vibrato, tremolo, or clever morphing if you want to dig into a bit of programming.

Another modern FM update is the inclusion of variable waveforms for each of the operators. In the original DX series, all operators produced sine waves only. Later models like the TX-81Z offered eight waveform options. In the Reface DX, each operator includes its own discrete feedback loop, which can skew the sine wave incrementally toward either a sawtooth or square. This is a lot more versatile than either of the previous approaches.

At the end of the synthesis chain is a set of effects that really help to fatten the sometimes “flat” sound of FM synthesis. Like the CS, there’s distortion, phaser, chorus/flange, and delay. You also get a touch sensitive wah (yes!) and a basic hall reverb.

The DX also includes the CS’s phrase looper for quickly sketching out ideas. But again, there’s no way to export loops other than audio recording into your DAW.

Conclusions. As a teenager, I spent countless hours teaching myself FM synthesis on Yamaha’s DX7 and TX81Z. Forcing my way around the synth’s two-line LCD was an exercise in patience to say the least. While the Reface DX’s more accessible user interface is a huge help for newcomers looking to explore the same territory, the real victory here is its timeless sound. Whether you’re a vintage buff or a modern EDM producer, the Reface DX could be a nifty addition to your rig.

Reface YC

The shiny red case of the Reface YC is a nod to Yamaha’s vintage A3 and YC-20 organs. It covers five classic organs: Hammond B-3, Vox, Farfisa, Ace Tone, and of course Yamaha’s YC series. In addition, there’s a built-in Leslie simulation, distortion, and reverb.

The sound of the B-3 is universally known, but unless you’re a die-hard organ nerd, it can be confusing to recognize each transistor organ’s defining sonics, so here are a few musical references for each.

Unlike the Hammond, which generated sound via spinning tonewheels and pickups, the other four organs all used transistor technology. The Farfisa sound can be found in pop tracks like “When A Man Loves A Woman” and “Crocodile Rock”, later being co-opted by late-’70s new wave bands like Blondie, the B-52s, and early Talking Heads. The Vox sound was similar but more flutey and less raspy and played the signature riff on “96 Tears” and pretty much every Doors song ever. In the new wave era, the Vox featured prominently in tracks from Elvis Costello, Madness, and the Specials.

Sounds.Each of the Reface YC’s five organs can be tailored via the nine drawbars, which follow a Hammond-style footage scheme. Note that Vox Continentals didn’t provide as many drawbars as Hammonds, and many popular Farfisas didn’t have drawbars at all, just stop tabs. This means the YC can create harmonic profiles that the originals couldn’t, albeit at the cost of strict authenticity. In any real musical use, the difference is negligible. Similarly, the percussion stops affect all of the transistor models in the same way.

Editor Stephen Fortner is a far bigger Hammond-head than I am, and having spent time with a Reface YC, he opined, “The B-3 and Leslie emulation are way better than I expected. Maybe a notch under a current top-end clonewheel, but just a notch. I’d totally gig with this.”

The only thing you might miss compared to a full clonewheel is that since the YC is a one-sound-at-a-time affair, you can’t set up parts for dual manuals (or add a bass pedal part) with different drawbar registrations.

Effects. Both the distortion and reverb are terrific, adding grit and space to the overall sound.

As Fortner noted, the YC’s Leslie emulation is a solid all around, especially when it interacts with the distortion, adding that hallmark milky grunge. The rotation speed is controlled on the fly via a lever that’s in the same spot as the pitch-bender on the CS and DX. To maintain accuracy, this is a toggle that spins up and down to “chorale” and “tremolo” speeds convincingly. A stop option emulates the sound of a braked Leslie, capturing its location in the stereo field at the moment of “stopping” and sounding completely different than just turning the effect off.

Conclusions. The Reface YC captures the sass and swagger of both rock ’n’ soul tonewheels and new-wavey transistors with equal aplomb. Performing on YC’s mini keys was a better experience than on the CP, perhaps due to the nature of organ versus piano playing. If you’re hoping to rely on it for more stretched out, two-handed rock playing—because sound-wise, you certainly could—you could add a MIDI controller or drive it from a zone on your stage piano and have a very capable and tweakable organ module at your fingertips.

- The best Yamaha keyboards available today