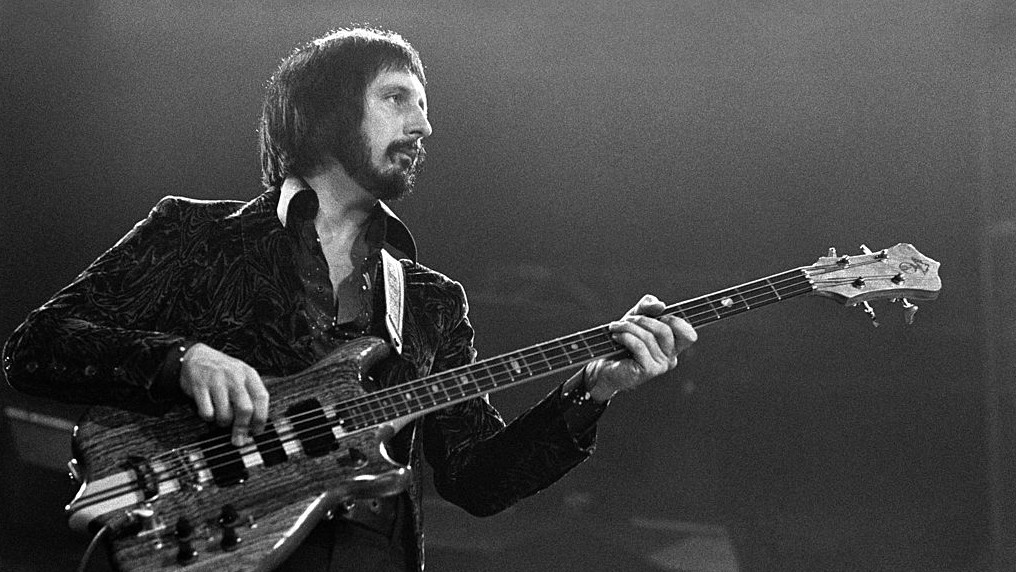

Why John Entwistle was the greatest rock bassist of all time

Following the 50th anniversary of Tommy, we pay tribute to The Who's legendary bassist

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The greatest rock bassist of all time? Quite possibly - but don’t take our word for it. Ask Lemmy, ask Geddy Lee, ask the readers of this and many other websites and magazines, and definitely ask Chris Charlesworth, chronicler of The Who and friend of the late genius, who pens this tribute on the 50th anniversary of Tommy.

"About time, too." John Entwistle could be forgiven for thinking such thoughts when, in 2000, Musician magazine named him its ‘Bassist of the Millenium’. A shame, then, that The Ox wasn’t around 11 years later when readers of Rolling Stone overwhelmingly voted him the greatest bass player of all time.

Today, of course, it’s widely acknowledged that John, who died in 2002, was the best rock bass player ever to plug in and shatter eardrums, but it was his misfortune that during the time when The Who were performing regularly, from 1964 to 1983, his skills were largely overlooked.

John’s relentless, twangy bass acts as the foundation on which his three colleagues could rip yet another stage to pieces

The golden era for The Who coincided with the release of their rock opera Tommy, 50 years ago this month. Although they’d already distinguished themselves on the concert circuit in both the UK and the US, this was the group’s breakthrough in terms of record sales. In many ways it was a showcase for John, who not only played bass throughout but also contributed vocals, including lead on two ‘nasty’ songs that Pete Townshend requested he write for his rock opera, as well as French horn, trumpet and flugelhorn.

John soon makes his presence felt. In the Overture to Tommy his French horn – the first solo instrument to be heard – takes on a melodic role in place of absent vocals, while in the indistinguishable instrumentals Sparks and ‘Underture’ his repeated descending bass figure defines the structure, the rigid staff around which Townshend and Keith Moon can improvise.

On stage Sparks would become a pièce de résistance of ensemble Who playing, with the band’s three instrumentalists reaching higher and higher towards block chord climaxes that characterised their style: the ringing open notes, the octave drops and wave after wave of escalating, bass-driven crescendos.

In Pinball Wizard, the best known song from Tommy, Townshend’s furiously strummed intro is punctuated by the thunderous boom of powerful guitar stabs that John famously reproduced live by hammering down on his bottom string. The finale to Tommy, See Me Feel Me with its turbocharged ‘Listening To You’ coda, is driven by rousing major chords while John’s relentless, twangy bass acts as the foundation on which his three colleagues could rip yet another stage to pieces.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Often overshadowed

All of this, coupled with increasingly earnest accolades from his peers, ought to have raised John’s profile as a bassist par excellence but in the period after Tommy’s release other players – most notably Jack Bruce, Chris Squire and Greg Lake – received many more votes in the ‘Top Bassist’ category of readers’ polls conducted by Melody Maker, then the benchmark by which instrumental prowess was measured. Indeed, in the 1973 MM poll John doesn’t even make it into the top 10 bass players.

Why was this? Well, despite my efforts as MM’s unofficial Who cheerleader, the paper gave far more coverage to Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer than it did to my favourite band, and Jack Bruce’s stint with Cream gave him an edge that never went away. Furthermore, despite his solo recordings John had the lowest of profiles within The Who.

What audiences missed was a display of extraordinary but inconspicuous fluency

Overshadowed by the wayward but fearsome intellect of Townshend, the lunatic exploits of Moon and the craggy good looks of Roger Daltrey, John early on realised the futility of competing, of doing anything other than simply stand there and play, a low-key approach unlikely to earn him votes from magazine readers. But I think there was more to it than that. John can best be thought of as a bass guitarist, perhaps even a guitarist who played bass, rather than a bassist. This distinction – which he made himself – is important.

“I found bass very boring,” he once said. “I wanted to turn it into a solo instrument and the only way to do that was turn up the treble.”

In another interview he even went so far as to say that The Who didn’t have a bass player. So it was that audiences never really appreciated what John was playing, because the sounds that came from his speaker stacks appeared to come from Townshend’s guitar, or even a pre-recorded low register synthesiser. Coupled with the guitarist’s attention-grabbing style – the leaping around and windmilling – not to mention the antics of Daltrey and Moon, no-one paid much attention to the chap on the left in the brightly coloured jackets who simply stood there and played.

What they missed was a display of extraordinary but inconspicuous fluency, a player whose technique involved not just plucking his strings with his thumb and every finger of his right hand, but also tapping them and switching periodically to a plectrum, bending, hammering on and pulling off notes. He employed vibrating trills and unexpected bell-like harmonics, glissandos that travelled the length of his entire fretboard, parts that echoed or reinforced lead riffs and vocal lines, and even chords strummed across two or more strings that created an all-enveloping wash of low- frequency resonance. What’s more, he made it look easy.

“John got attention simply because he stood so still, his fingers flying like a stenographer’s, the notes a machine-gun chatter,” wrote Townshend in Who I Am, his 2012 autobiography. “And through it all, as if to anchor the experience, John stood like an oak tree in the middle of a tornado.”

Home for tone

After a break of seven years Townshend agreed to tour again with The Who in 1989, but he stipulated that because loud noise had damaged his hearing he would do so only if John significantly reduced his on-stage volume, a condition that required The Who’s stage personnel to be substantially reinforced. With Simon Phillips now on drums, they were augmented by a further 12 musicians, all to compensate for John turning down.

“The only way we could add [John’s] harmonic richness,” said Townshend, “was to add brass, second guitar, acoustic guitar, two keyboards, backing vocals and people banging gongs, because that’s what John used to replicate.”

“He had a technique that was light years ahead of everybody else at the time,” said keyboard player Rick Wakeman, who studied at the Royal College of Music. “Nobody played like John.” “Best bassist in rock ’n’ roll,” added Lemmy. “No contest.”

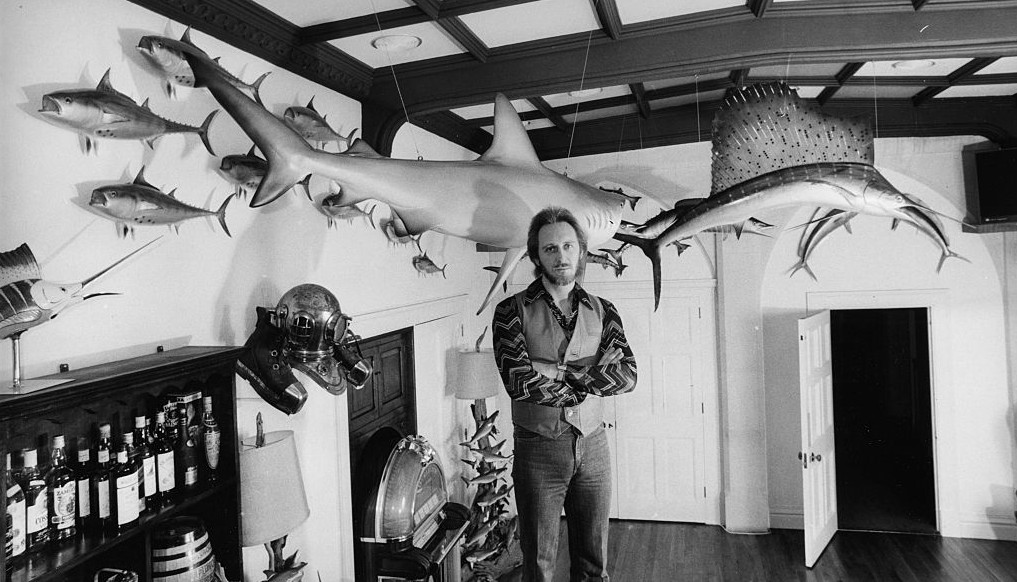

The house was full of curios: part museum, part instrument store, part studio and part home

In the third week of December, 1972, I visited John at his semi-detached house in the west London suburb of Ealing, ostensibly to interview him for Melody Maker about his second solo album Whistle Rhymes. By this time I had edged myself into the role of MM’s unofficial ‘Who correspondent’ and charmed my way backstage at several concerts, so I knew him reasonably well. He was a friendly, down-to-earth man, quite softly-spoken and reserved when he wasn’t performing, and he took compliments like a pinch of salt, wryly amused by his reputation as a disciple of the macabre; “big bad black Johnny Twinkle,” as Moon once yelled on stage, to which Townshend added, “with the flying fingers”.

John and his wife Alison welcomed me into their home. It was the kind of house you might expect a moderately successful businessman to occupy with his family, comfortable but not ostentatious, perfect for the character in The Kinks’ song Well Respected Man. Some wags within the Who camp were suggesting John should run for Mayor of Ealing.

The house was full of curios: “part museum, part instrument store, part studio and part home,” I wrote in MM. He had just bought a table lamp with those swishy frond-like tentacles that lit up at the ends and I’d never seen one before. Nowadays they’re a bit kitsch but I was fascinated by it.

Even more impressive was the first video recorder I’d ever seen, a contraption the size of the average microwave with lots of knobs, and cassettes like cigar boxes. John demonstrated it for me, and then took me upstairs to admire his collection of guitars and basses. Outside of a music shop, I’d never seen so many guitars in one place. He told me he had 32, which was nothing compared to the number he would eventually amass.

In 1975, flush with funds accrued from the Who’s US success, John and Alison moved to a preposterously large mansion on the southern outskirts of Stow-on-the- Wold in Gloucestershire, about 85 miles west of London. Approached by a winding drive through trees and shrubbery, Quarwood was a gothic Victorian hunting lodge completed in 1859, with 42 acres of land, seven cottages and 55 rooms, its cantilevered staircase leading to a gallery where gold and platinum records were displayed floor to ceiling.

Many of the bedrooms housed John’s instrument collection which, in the fullness of time, would grow into one of the largest guitar collections belonging to any rock musician. Another was given over to his electric train set. Medieval suits of armour stood in the hallway where, dangling from a noose, was a stuffed effigy of Quasimodo eyeing the skeleton that reclined in an armchair.

Fan’s man

Unlike the semi in Ealing, it was the epitome of rock star indulgence and although it seemed to me as it if it was permanently in need of a coat of a paint and a bit of building work, the master of the house was as proud of his chattels as any 18th Century Lord of the Manor. “My father loved the house and Stow,” says John’s son Christopher, who put the house and most of its contents on the market after his father’s death. “Everyone knew him there but they gave him plenty of privacy and he was never bothered by anyone.”

About 90 of John’s bass guitars, among them several instruments that he had played onstage with The Who, were sold in 2003 at Sotheby’s Auction Room in South Kensington, along with a similar number of guitars and many brass instruments. The sale, which also included Who memorabilia, stage clothes, antique chandlery and casts of game fish, raised about a million quid.

Fans deeply appreciated not just John’s immense skills as a musician but the touching allegiance he had always shown towards them

Watching the auctioneer’s hammer come down alongside me were grieving fans eager to bid for a little piece of John Entwistle. In the last decade of his life they had seen him performing not only with The Who but also with bands of his own, and the lack of renown he’d suffered in the early part of his career was now a thing on the past.

These loyal fans deeply appreciated not just John’s immense skills as a musician but the touching allegiance he had always shown towards them. Within the Who fan community it had become well known that after both his own and Who shows, John would remain behind to socialise, happy to answer questions about his equipment, his playing style and The Who, and sign autographs for one and all.

I cannot think of any other rock star of his stature who was more gracious to fans, the lifeblood of the music industry after all, than John, nor fans who appreciated this princely attitude so much. The last time I spoke to John was backstage at Wembley Arena after a Who show on November 15, 2000. The hospitality area was crowded with men and women far younger than me or the group and there was no sign of Townshend or Daltrey but, as ever, John was in the midst of the throng. Grey-haired and looking older than his 56 years, he was slightly tipsy I think, and when he saw me he offered a warm smile of recognition. “I don’t know a soul here apart from you,” I said to him. “Neither do I,” he replied, laughing.

Thanks to the miracle of modern technology it is now possible for fans to watch John playing on two Who’s Next songs, Won’t Get Fooled Again and Baba O’Riley, and hear his bass-lines isolated from the vocals, guitar and drums. These extraordinary clips, made available for the first time on a bonus disc with the 2004 reissue of the Who documentary film The Kids Are Alright, can now be found on the internet and have, at the time of writing, attracted nearly two million views for WGFA and well over a million for Baba O’. John’s now famous solos in The Who’s Dreaming From The Waist and 5.15 can also be viewed, as can bassists who demonstrate John’s techniques.

Finally, a full length biography of John is due to be published by Constable in October. Written by Paul Rees, a former editor of Q and Kerrang!, The Ox: The Last of the Great Rock Stars: The Authorised Biography of John Entwistle is sanctioned by John’s estate and features contributions from Alison and Christopher, his cousin and stepbrother, and John’s second wife, Maxene, along with many from the Who camp, including manager Bill Curbishley and Who soundman Bob Pridden who operated John’s studio at Quarwood.

Rees also had full access to John’s archives, including several chapters of an unpublished autobiography that John had completed. About time too.

Chris Charlesworth is the co-author, with sleeve designer Mike McInnerney, of Tommy At 50, published by Apollo, for which Pete Townshend has written a foreword.