You don't need to be a music theory expert to make electronic music, but it helps - here's our guide to the basics

Understanding the theory behind what makes a song work can be the difference between a flop and a hit

As an electronic musician, it’s important to be able to create and finesse the sounds of your productions. The ability to craft unique synth patches, shape and sequence distinctive beats and layer, mix and balance track elements are all essential strings to add to your bow.

But these abilities amount to very little if they’re not deployed in the service of a good song. Whatever genre you’re working in, the success of your track lives and dies on the quality of the core idea.

Working with beats and being a genius sound designer are great, but creating a standout track also requires knowledge of how these elements fit together; understanding how notes interlock, beats and basslines groove and how a central melody can truly engage the listener.

At their simplest level, all songs can be boiled down to ‘a tune’ – a series of notes that play one after another. When more than one of these notes plays simultaneously, it creates a chord.

Putting chords in series creates a progression, and putting melodies and basslines alongside this creates a song. Some songs can be four chords repeated in a loop, others a complex never-repeating sequence, but all become music as soon as you follow one chord with another.

A lot of great dance, pop and rock music has been made by self-taught musicians with limited knowledge of the theory behind what they’re doing

All of which is very basic music theory and, of course, music theory can get far, far more complex than this. As an electronic musician it’s debatable how deep you need to go.

A lot of great dance, pop and rock music has been made by self-taught musicians with limited knowledge of the theory behind what they’re doing. It’s perfectly possible, for example, to create melodies or chord progressions entirely based on what sounds appealing to your ears without really understanding what key you’re working in or why some combinations work while others don’t.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Many electronic musicians regularly experiment with fairly complex musical concepts such as microtonality or polyrhythms without fully exploring the theory behind them (or even realising they’re doing so in the first place).

It’s worth pointing out, of course, that rules are made to be broken, and there are plenty of incredible ambient, minimal and general electronic tracks that rely completely on texture and evolving modulations to evoke emotion, as much as the use of certain chords and melodic phrases.

Following the ‘rules’ of music doesn’t always equal a great track and vice versa. However, relating what you hear and do to a music theory frame will give you a new and important perspective, whether you make three-minute pop songs or fifteen-minute, one-note ambient textures.

Why keys matter

Picking the right key is an often-overlooked part of music making but can have a huge effect on your track. Why? Well firstly, your song’s key denotes its overall feel and vibe.

Getting it wrong – or changing it for effect – can make a happy tune sound dark or vice versa, and therefore never quite right for reasons you’ll never be able to work out.

Bear in mind too, that there is a certain resonance in bass, and once you fall below it, you’ll ‘feel’ it more than you’ll ‘hear’ it. A lot of drum & bass tracks are in G, for example, as low G is a highly resonant bass frequency.

Fortunately, modern production gear makes experimenting with different keys incredibly easy

Each key has its own unique character and mood. D major (for example) has a totally different vibe to A major. More on chords coming up. Secondly, different vocalists and instruments sound best in certain keys and ranges. If you choose a key that is too high or low on the keyboard your vocal range could suffer. Similarly, when it comes to synths, filters or oscillators will often respond differently at different frequencies, so shifting your track up or down in key could drastically alter the tone of an instrument.

Fortunately, modern production gear makes experimenting with different keys incredibly easy. Many sequencers, both in hardware and software forms, offer some form of transposition tool that will let you shift melodies and chord progressions around to different keys, while the multitude of MIDI devices contained in most DAWs mean that, even if you’re happy with the key you’re working in, it might be worth quickly trying a few alternatives just for the sake of experimentation.

Major and minor chords

Chords, like we say, are notes that play together. They’re stacks of notes built with notes taken from the key (also known as ‘scale’) of your track. They also act as vital ‘harmonic glue’ and provide the framework that ties together your bass and your lead elements. Think of the bass and beats as the main unifying drive of the music, melody lines as the icing on the cake and harmony as the true body and soul of your music.

You’re probably aware of major and minor chords. Each has a distinct sonic quality that makes major chords sound ‘happier’ and are therefore ideal for happy, uplifting and brighter tunes, while minor chords are the way to go if you want darker or more minimal.

Going from major to minor chords is one of the most powerful harmonic devices you can use

As a general rule, three-note chords are defined as major or minor by the middle note in the chord. An easy way to work out if a chord is a major or minor is that if the middle note in any three-note chord is four notes up from the root note (aka the bottom note) then it’s a major chord. But if the middle note is three notes up from the root note then it’s a minor chord.

Let’s take the chord G major (G-B-D) for example. Hit these keys and you’ll hear a bold, resonant, strong chord. Now shift the middle note a single key down from B to Bb to create a G minor. That’s a change of just one note but a totally different mood.

Going from major to minor chords is one of the most powerful harmonic devices you can use and really helps take the listener on an exciting journey. Try holding any three-note chord then moving one finger at a time, each one in turn. You’re modulating between major and minor chords as you go.

Writing a lead melody

What do you want the tune of your next track to do? What do you want it to make the listener feel? Euphoric? Sad? A sense of indestructibility? Empathy? Do you want it to help those listening to fall in love? Or do you want it to be imbued with some other quality?

As this subject is huge, we’ll begin the process of being a little more tactical with the notes we write, to help wrest a greater emotional arc in our melodies. Because ultimately, that’s what a melody is; a tune which encourages the listener to feel emotion, no matter which of the many emotions you want to tap into. The melodies we forget are those which leave us unmoved; the ones we remember can bear repeat listening because we want to feel the emotions they provoke over and over.

As a rule, a great melody requires a combination of tension and release

But exactly how this process works isn’t a precise science, and it’s true that one person’s idea of a great tune will leave another person cold, which is why so many of us are still writing new music; despite all of the melodies which have gone before, there are many left as yet unwritten.

The quickest approach for coming up with a tune or hook is to simply look at the notes within your chord progression to fuel your melody (or bassline). You can use the top notes from your chord progression plus notes taken from within your three- or four-note chord shapes to create your melodies.

As a rule, a great melody requires a combination of tension and release. The tension comes when a melody line plays against the harmony in a way which produces a moment of musical ‘jarring’; the release comes when that moment is resolved and the melody changes to support the harmony, or vice versa. Melodies which only use notes from the chords which accompany them often lack musical depth, while melodies which only ‘jar’ and never resolve are often hard to connect to or to translate into human emotions.

Hopefully some of the examples that we’re looking at in the following walkthroughs will help you to find the balance between those states…

Breaking the rules of harmony

For every key you can write in, there is an ‘expected’ group of chords which sound ‘right’. Sometimes, breaking this expectation provides a more memorable melody.

In the first step of the following walkthrough, we’ve explored the scale of C minor and drawn up all of the associated harmonic chords with each of its root notes.

If you use any of the bass notes and write a melody which uses any of that note’s associated harmonic accompaniment, you’ll write a melody which makes ‘perfect musical sense’. But it may not be the world’s most interesting tune. By the third clip, we’ve boldly made the fourth chord not an F minor (as per Step 1) but an F major instead, shifting the accompanying note to A.

In C minor, here is the scale (the bottom note) and the associated ‘third’ note of each chord. If you write a harmony part using any of these bass notes and a melody line from the notes above each one, you’ll find that you can’t go too far wrong.

This melody is a good example. We’ve called it ‘safe melody’ as all of the notes and the supporting chords come from the options listed in the chord set in Step 1. The melody is slightly melancholy with no surprises. It’s very comfortable and a little predictable.

Here, things go a step further. Most of the chords are from within the chosen set, but we’re choosing to warp one chord – the one where F plays in the bass – and make this an F major by changing the ‘expected’ G# above it to an A. Suddenly the harmony provides a ‘lift’.

The power of inversions and chord voicing

By inverting the notes of a chord, you can ‘re-voice’ them to add greater lift to a track.

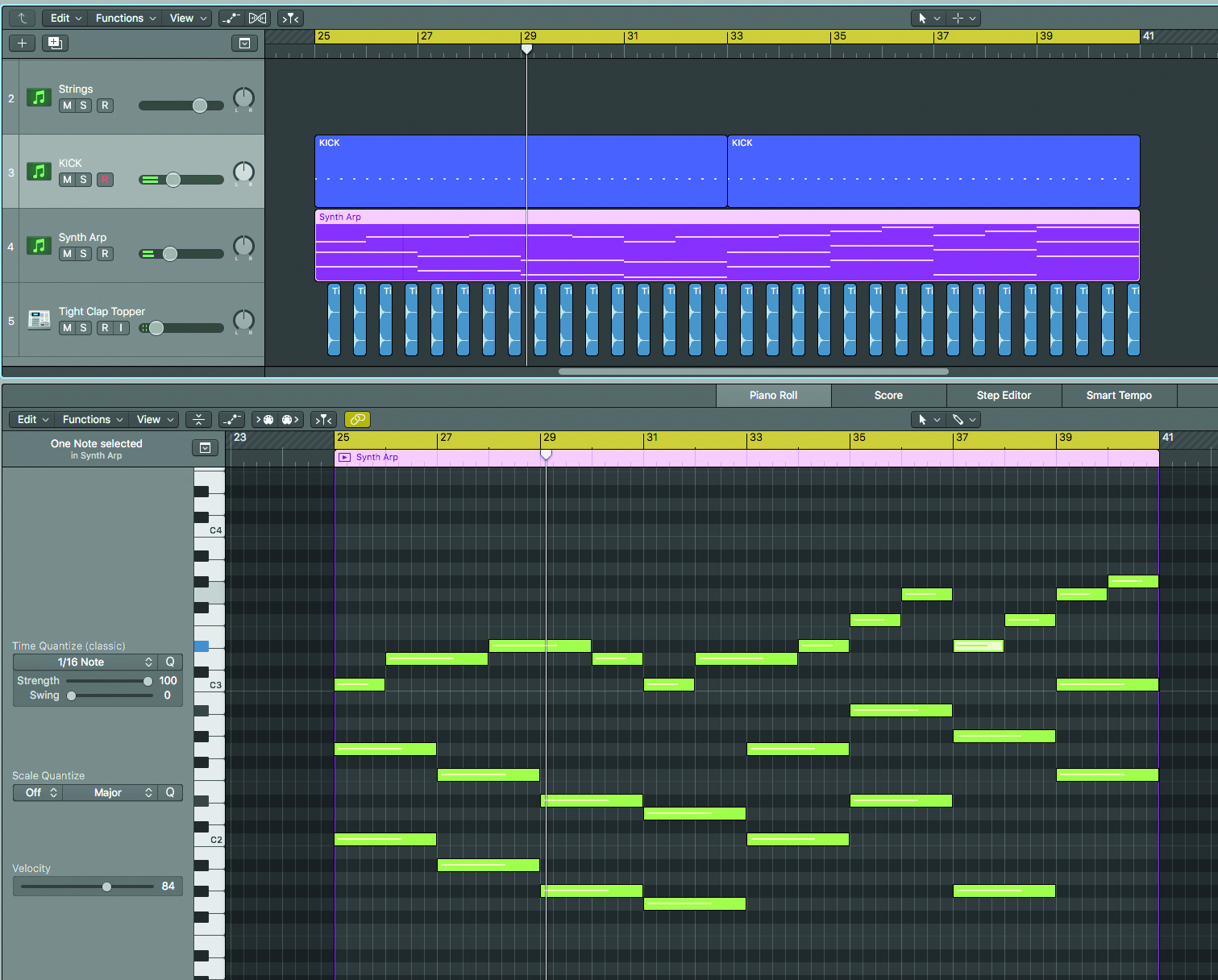

We want to write a euphoric synth sequence that acts as a real lifter, and we’ve got some chords with potential: A minor, G major, C major, D minor, C major, F major. Here is each chord, one after the other – one per bar.

There’s no rhythm to the sequence yet, which isn’t helping the vibe, but the fact that some chords ‘drop’ in pitch also results in a loss of energy. Look at the second chord after the first – all three notes drop in pitch, as we’ve played a G in the bass of the second chord.

We can invert the second chord by rearranging its notes. It’ll still be a G major chord, but if we put a rising note in the bass – B – we’ll have created an inversion. An inversion occurs whenever the root note is moved to a different note from that chord.

This lets us re-voice and lift the notes of the rest of the chord and that of the C major chord after. We can do the same thing with the second three chords, inverting the C major chord in bar 6, so an E is in the bass.

We can now add ‘euphoria’ to the rhythm too, to emphasise the upward movement. We copy each note to create the same syncopated pattern in each bar. This lets us hear even more the effect of each rising chord.

We add pad and bass parts. In the first clip, we play only ‘root position’ versions of each chord. Despite the synth sequence continuing to rise, it’s ‘pulled down’ by the bass and pad parts. By copying the upward movement to the two new instruments (second clip), we then can reinforce the upward movement.

Using passing notes to create basslines

While, in theory, a variety of notes can underpin any chord within your track, most of the time either the root note of your chord or another note directly related to that chord will sound most ‘comfortable’. In other words, if your track is in G minor, a bass note playing the note G will sound most ‘rooted’ under the chord, with either Bb or D having the potential to work well, too.

Whenever you have a chance to add colour between chords by using passing notes, it’s worth seeing if your bassline sounds richer for this extra colour

However, this is where things get tricky, as sometimes other notes can be effective too, particularly if you’re looking to write a bassline which transitions from one chord to the next smoothly. Let’s suppose the second chord of your track is an Eb major chord. As the bass note drops from G to Eb to reflect that change, you might well find that an intervening note – otherwise known as a passing note – of F will feel musical and natural, as it’ll help to emphasise that the bass end is dropping in pitch.

Of course, that F doesn’t relate precisely to either the G or the Eb chords, so it’s not ‘in tune’ with either chord directly. That’s not to say it won’t sound good, though, which is less of a surprise when you consider that plenty of musical genres rely on more interesting harmony than simply underpinning each chord with the root note at all times.

Whenever you have a chance to add colour between chords by using passing notes, it’s worth seeing if your bassline sounds richer for this extra colour. Passing notes might not always work but when they do, they’ll sound musical and considered. As is always the case though, don’t be afraid to experiment. Passing notes are just one idea to help you add melodic interest to your compositions, but don’t be afraid to try other things. There are no hard and fast rules – if it sounds good to you, then go with it!

Working with melodic suspensions

Delaying the resolution of melody notes produces a powerful musical technique we call a ‘suspension’.

We start with a simple melody, accompanied by a new bass note every bar. We’re in C minor and as the melody steps up through three bars, the bassline steps down. Both drop on the final chord. So the bass moves from C, through Bb and Ab to arrive on G for the last bar.

There’s no tension in the melody because each phrase of the tune resolves ‘perfectly’ on each downbeat of the bar. So the tune hits a D over the Bb (part of a Bb chord) and an Eb over the Ab and so on.

Let’s extend the duration of each of the previous notes before each resolves, so that there’s an ‘overhang’ at the beginning of each new bar. We call this a suspension, as it suspends a note before letting it resolve. This tension and resolution is powerful.

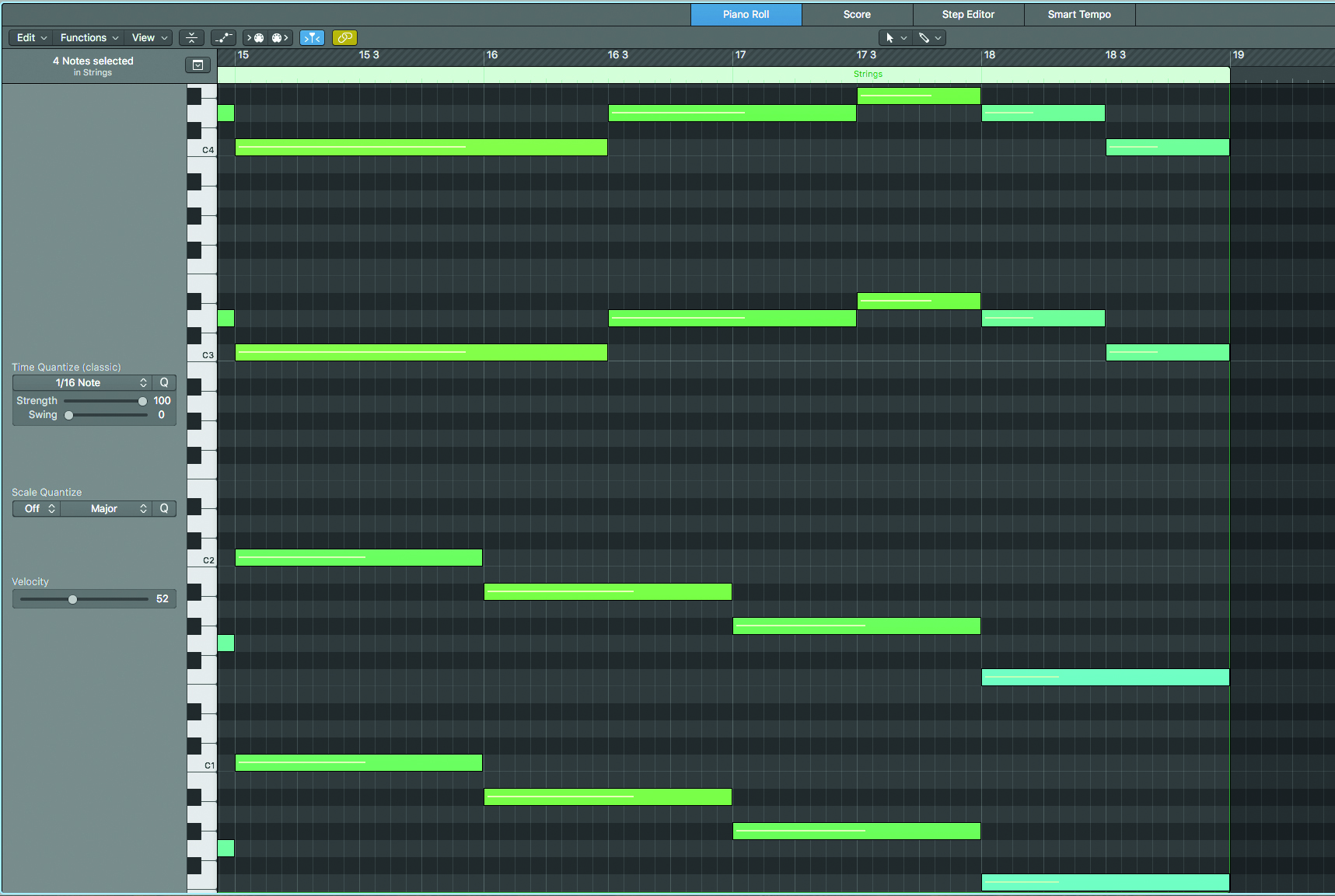

Let’s take our piano melody and arrange it for strings now. We’ll start with a cello line playing the bass part and violins playing the tune. Each suspended note uses MIDI controllers to ‘peak’ in intensity at each bar line’s suspension, before resolving.

Let’s extend our melody and harmony. It’s dull just to repeat the notes exactly, so create a new four-bar shape, using C – Bb – Ab – F minor. Now the end of our phrase can resolve down through two steps in order to reach a C, prolonging the tension further.

Here’s the same track rearranged as a dance track. We’re starting with the same chord progression and then moving onto new chords but the idea is the same; by suspending the resolution of each melody note against its harmony, the melody has more interest.

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers...

- GEAR: We help musicians find the best gear with top-ranking gear round-ups and high-quality, authoritative reviews by a wide team of highly experienced experts.

- TIPS: We also provide tuition, from bite-sized tips to advanced work-outs and guidance from recognised musicians and stars.

- STARS: We talk to musicians and stars about their creative processes, and the nuts and bolts of their gear and technique. We give fans an insight into the craft of music-making that no other music website can.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.