Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nearly 20 years after his death at the age of 52, Harry Nilsson is still best known to the masses for a pair of Grammy-winning performances of songs he didn't write (Everybody's Talkin' and Without You), a couple of numbers he did write but were hits for other artists (One, recorded by Three Dog Night, and Cuddly Toy, which was cut by The Monkees), along with two self-penned novelties: Coconut, featured in the closing credits of Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, and Best Friend, the theme to the late '60's/early '70s TV show The Courtship Of Eddie's Father.

It seems that Harry Nilsson's legacy simply won't behave, and in some perverse way that's fitting, because he certainly didn't like to color inside the lines, either. His songs moved like no other pop tunes of the time, floating along on waves of wordplay and melodic intervals before, finally, caressing your funny bone or stabbing you in the heart (or both).

Of course, there was that penetrating, sterling voice of his, a rare gift on loan from God before He wanted it back, and Harry was all to willing to oblige, drinking, smoking and drugging to excess before finally blowing out his pipes during an extended bit of carousing with his friend and hero John Lennon in 1974.

Harry's wild ride with the likes of Lennon, Ringo Starr, Keith Moon and other members of rock royalty is a sizable part of the narrative of Nilsson: The Life Of A Singer-Songwriter, Alyn Shipton's definitive biography on the late musician, but the author also examines Nilsson's creative lineage with exacting detail, chronicling the impulses behind a body of work that drew the heavyweights of music into the orbit of the enigmatic and troubled singer-songwriter like moths to a flame.

Coinciding with the release of Shipton's book is Nilsson: The RCA Albums Collection, a sumptuous 17-CD box set from Sony Legacy that includes all of the singer's discs for the label, from 1967's Pandemonium Shadow Show to 1977's Knnillssonn, along with three bonus CDS of rarities, demos, early takes and alternate versions, many of which are previously unissued. For armchair fans, it should prove to be an ear-opener, and true Harry-o-philes will consider it indispensable.

Alyn Shipton sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about Harry Nilsson, the man whom Paul McCartney once called his favorite American artist and whom John Lennon, at the same time, cited as his favorite American "group."

It's hard to spot the influences in Harry's music. Even in his early work, he seemed to arrive as an artist fully formed.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Well, yes and no. I think that's true in the sense of his subject matter and the way he delivered it was unlike anybody else. I like the idea that [music publisher] Perry Botkin described it in the book, that Harry's idea of how to write a song didn't depend on the same chords that everybody else used. Right away, you have somebody who's thinking of songs in a new way.

"The things that Harry always said were influences - The Everly Brothers, Ray Charles, The Beatles, obviously - they're all rolled in there. Sometimes it's a question of how he put them together, but quite often, you can hear echoes of those things. One thing I tried to do in the early part of the book was to see if there was a Buddy Holly song or an Everly Brothers tune or a Rolling Stones song that influenced him."

What's interesting, though, is that Harry seemed to come to music naturally - or it came to him, I should say. He didn't have an "Elvis moment" or even a "Beatles moment" that defined his decision to pursue music.

"I think this goes back to his singing uncle. There he is, first as a schoolboy and later as a teenager, with John Martin, who was always a natural singer. I think a lot of that went into Harry. Of course, John Martin was horrified when Harry's mother tried to get him a contract and actually brought a scout to come hear him. They didn't speak for months afterwards.

"But think about it: There's Harry, working in a garage and moving tires around, getting engine oil and all those things, but the whole time he's listening to his uncle sing. Back at home, he also had his grandmother playing the piano. There were musical influences. As you say, there wasn't an epiphany moment, but he was surrounded by music and musical people."

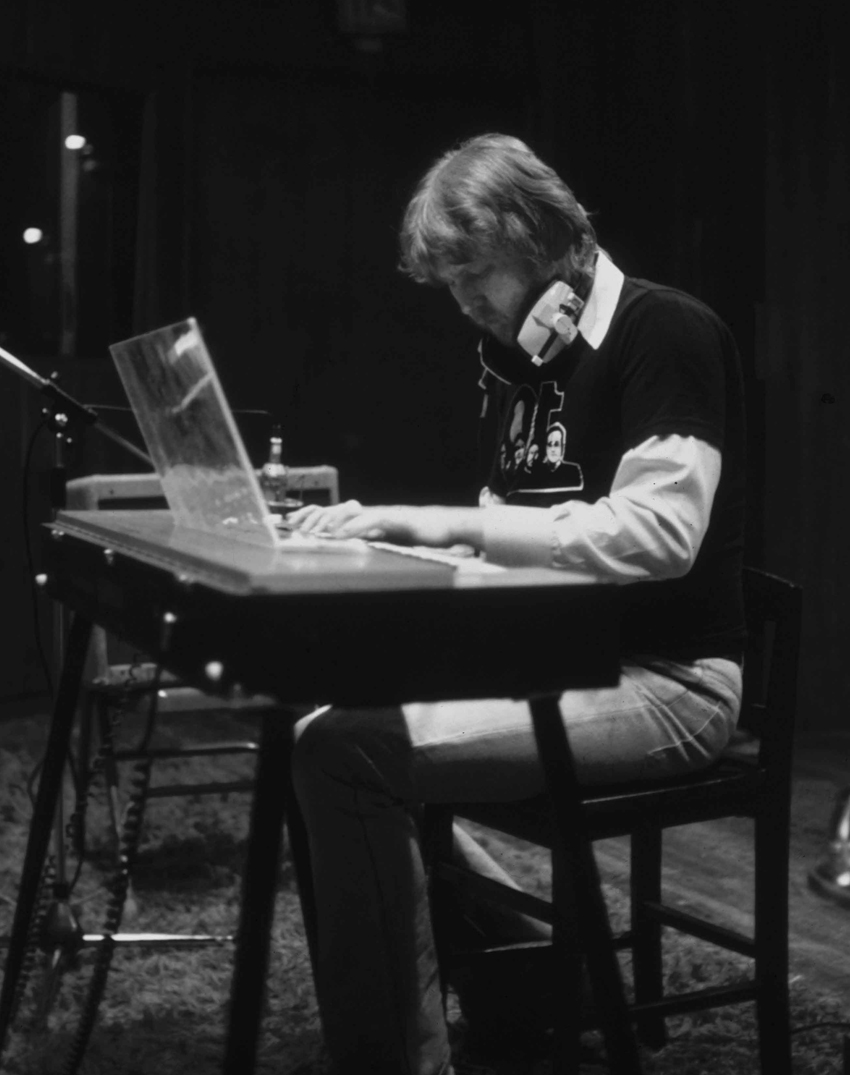

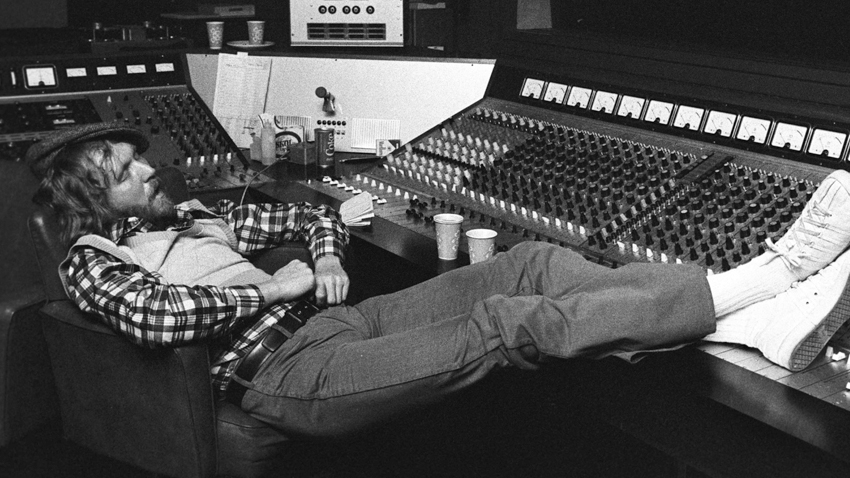

© Sony Music Archives

Harry didn't have the same kind of apprenticeship that The Beatles and so many artists had back then. He didn't play the clubs for years before he was discovered.

"That's true, he didn't. This may have had a lot to do with the fact that he didn't like performing in public. That business of getting up in front of people night after night, dealing with hostile audiences, winning them over, was never part of his aesthetic at all. He might have been very good at it if he did come up that way, but his circumstances were quite different."

Do you know if he did see The Beatles when they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show?

"I wouldn't mind betting he did, but there's no hard evidence that says so. I do know that when he and John Marascalco wrote All For The Beatles - Stand Up And Holler, which was an eight-millimeter film and single combination - it was a kind of early attempt at a music video - they used all the clips from American newsreels of The Beatles arriving in New York, going to play on Ed Sullivan and the two concerts they did on the East Coast during their very brief first visit to the States. Obviously, if he had access to that film material, and he would've because the lyrics were timed to work with the way the film was cut, I wouldn't doubt that he saw a recording of the show, even at the time."

I've always thought that Harry's aptitude with numbers - working in a bank and with early computers - carried over to his songwriting. His wordplay and rhyming schemes have an almost mathematical approach, with combinations of words substituted for digits.

"You'd think that was even more true if you went through the boxes of bits of paper with lyrics written out on them. Harry very seldom revised; what came out and was written down, sometimes in block capitals, was what the lyric often was in his head. The words on the page had already been decided on.

"I think you're right, that because of his mathematical skills and the fact that he didn't have to write things down, it was reflected in how he put lyrics together. In the book, I mention the song Coconut and its alternate lyrics: "Whisky makes you ill and then you take whisky to feel better." That sort of duality, and in many cases, his repetitive ideas, was something that he tried working out. I suppose the big theme in the book was the number of different ways he tried writing about father abandonment."

Do you think he bonded with John Lennon over their mutual feelings of father abandonment?

"I have no idea what they talked about that first night, when Harry was in London for three days during the making of the film Skidoo. He said he stayed up with Lennon all night and came away with the fur coat that John wore on the cover of Magical Mystery Tour, even though it was a couple of sizes too small for him.

"I imagine they talked about it. What do you do when you meet somebody for the first time? You talk about your shared interests and experiences. I'm sure that their backgrounds and how they came into music would have been part of that discussion. What's really clear, though, is that meeting was start of a long friendship, and it was deeper than his long, very robust friendship with Ringo."

Did John and Harry keep in touch with each other during John's five-year seclusion period?

"As far as I know, they did. There were certainly letters going to and fro. The thing about Harry's correspondence is, it's pretty patchy; some of it survived, some of it didn't. When he had an assistant working for him who bothered to keep copies of things, you can see that Harry made big efforts to keep in touch with lots of people, lots of the time. There are the odd indications that he kept up with Lennon."

Going to London to work with Richard Perry on Nilsson Schmilsson took Harry out of his LA comfort zone. He had to give up a fair amount of control for what would be his only big hit album.

"Yes, and I think Richard demanded that. What we have to think back on, when the two met in the early '70s, it was still a very new idea for a record producer to work as an independent and then sell the results back to the record company, even if the artist was signed to the very same label. The floating record producer wasn't well-established, and Richard was in the running; he was out there as a new breed of producer. I think that Harry's taste for the new made Richard appealing to him.

"The kind of craftsmanship that Richard brought to Harry, certainly on Nilsson Schmilsson, making the most perfect take of every song and then compiling it like two acts of a play, very seldom happened with an in-house producer - there are a few but not many."

Harry's drinking and drug use escalated during this time, but it doesn't seem as though there was a trigger for it.

"Well, his second wife, Diane, said that this came with success. If you think about it, right the way up to making Nilsson Schmilsson - and Everybody's Talkin' doesn't really get the recognition and the Grammy until after work had started with Richard Perry - Harry hasn't really had success, and he's hungry. In his work with his first producer, Rick Jarrard, they were always working on the next album before they even finished one.

"Harry traded success for hunger. He was never a fat cat resting on his laurels; he was always working. But the ability not to be keeping the wolf from the door, and the feeling that the poverty he'd grown up in was just around the corner, it all blissfully went away. He was getting sizable advances, he was earning a lot in royalties, and he was able to indulge himself. During the years that he was fighting for success, he'd held back. Now he didn't have to."

© Sony Music Archives

Richard Perry says in John Scheinfeld's documentary that he thinks Harry had a death wish. What do you think?

"Richard wasn't the only one who thought so. Almost everybody I've met who knew Harry to some extent saw this in him. There was an element of him that could not pull the joystick back and get the plane out of the final dive. It's tragic, but it seems to be true. There were only two or three people who arrested the momentum of that decline: One person was his third and final wife, Una, who was a tremendous influence on stabilizing Harry; she very much averted the speed of the decline.

"Ringo did, as well, although they indulged in all kinds of hedonism; nonetheless, the friendship with Ringo helped to steer Harry through. He was making advertisements for Harry's charities towards the end of Harry's life."

It's interesting: Harry's friendships with both John and Ringo didn't always result in great work.

"I don't know about that. If you look at Ringo's album, you see the continuation of being able to work with Richard Perry. You're Sixteen is one of Harry's greatest vocal performances."

That track, yes, is amazing.

"And you can see Harry's influence on the Goodnight, Vienna album, as well. I think it's not cut-and-dried, but you are right in the Lennon relationship. Harry's contribution to Walls & Bridges is not great, and the one or two other things they collaborated on had some problems. The quad mix of Pussy Cats, though, is the great album that might have been; it's a much better mixed version than the stereo version that came out. But how many people had quad sound in 1974?"

Son Of Dracula wasn't a great film, or even a good one, but Harry did exude a strong on-screen presence. Do you think the idea of acting appealed to him after the movie?

"Well, I think it would've because his teeth were much better. He'd had terrible teeth, and I think his fee for appearing in the film was that Ringo would have his teeth fixed; they used to protrude terribly and were uneven. On the early albums, people said he would never smile with his lips apart because he was embarrassed about his teeth.

"You'd think, given a change in his appearance and some very good reaction to his own performance, that it would have been to have seen more of him, but it's never something he did. He was also pretty good in The Ghost & Mrs. Muir."

I'm glad you brought that up. I always liked his appearance on the show.

"He's so incredibly cool in the middle of this ham acting. When we think of Edward Mulhare as the ghost and this arch voice in Knight Rider, he's this completely ham actor. And then there's Harry, who is totally natural - you get the feeling that he was very comfortable in front of a camera. He wasn't always in love with performing, not at all. But when you see him in the studio doing those two BBC specials, that's a very relaxed person in front of the camera."

What's the status of the unreleased album Harry did with Mark Hudson? Do you think it'll ever see the light of day?

"Well, two tracks have come out in limited editions, on releases from his music publishers. I've heard those, and the implication is that it's an OK album but won't set the world on fire. I've not heard the rest of it, but it's interesting that no more of it has surfaced given the interest in this 17-CD set. Obviously, the record was after the RCA contract, but there are a number of things on the RCA set that give us the impression that the company went far and wide to ensure that the demos are out in their rightful place."

There was a YouTube video floating around recently, "Would John Lennon have made it on American Idol?" A lot of rock legends - Lennon, Springsteen, Dylan - probably wouldn't have cut it, but I think that Harry - prime Harry - would have.

"His voice was unparalleled. In so many ways, he was the perfect singer. I think that if his dislike for appearing in that kind of setting could have been overcome, he would have triumphed. You're absolutely right on that. Harry had all the gifts one needed to be one of the biggest artists of all time. This is one of the great "What ifs?" But I think there's something intangibly special about all the artists you named that would have won an audience over - we don't quite know what it is. Harry had all of those intangibles, as well, in addition to a voice that could just take your breath away."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.