Rudy Sarzo: “Randy Rhoads put his reputation with Sharon and Ozzy on the line to bring me in - I had no track record”

The ultimate rock bass journeyman on his time with Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake, The Guess Who and more

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Rudy Sarzo is a hero of no fewer than six decades of bass. In the '60s, as a Cuban refugee living variously in New Jersey and Florida, he plucked the bass in garage-rock bands.

In the '70s, he made his bones with Quiet Riot, pioneers of Hollywood’s hairmetal scene. Catapulted to fame in Ozzy Osbourne’s band in the '80s, courtesy of a recommendation from his erstwhile Quiet Riot colleague Randy Rhoads, Sarzo toured the planet with bands such as Whitesnake. By the mid-'90s he was a classic rock bassist who commanded enormous respect, laying down lines with Yngwie Malmsteen, Dio and Blue Oyster Cult in the decade that followed.

In recent years Sarzo has trodden the boards with Geoff Tate’s version of Queensryche, Animetal, and now The Guess Who, where he continues to tour today. He’s a bassist with much wisdom to impart, and where better to share it than in these pages? Read on as he talks essential gear, professional attitudes, dealing with the still-shocking tragedy of Rhoads’ death in a plane crash in 1982, and the skills you need to take the big sounds to the big stages...

How’s it going with The Guess Who, Rudy?

A lot of people think of me as a heavy metal bass player, but I started playing before metal existed as we know it

“It’s going great. I started playing in the '60s, and I know a lot of people think of me as a heavy metal bass player, but I started playing before metal existed as we know it. So the Guess Who’s music was part of the soundtrack of my life.

“We had a new record out a few months ago [The Future Is What It Used To Be] and we’re playing songs from it. It was really well-received, so it’s all good. They keep adding dates, and then in March all the spring tours begin.”

Do you still enjoy life on the road?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Oh yes. I know from doing this for so many years that a band like ours has a certain routing, dedicated by flying. A lot of bands in our situation avoid travelling in winter time, and pick it up in March.

“But I remember going on tour with Ozzy, when [his wife and manager] Sharon Osbourne really wanted to establish him as a solo artist by playing the A, B and C markets. She saw it as an advantage for us to tour in the winter time in the United States, because there would be less competition. There’s different schools of thought.”

What gear are you using?

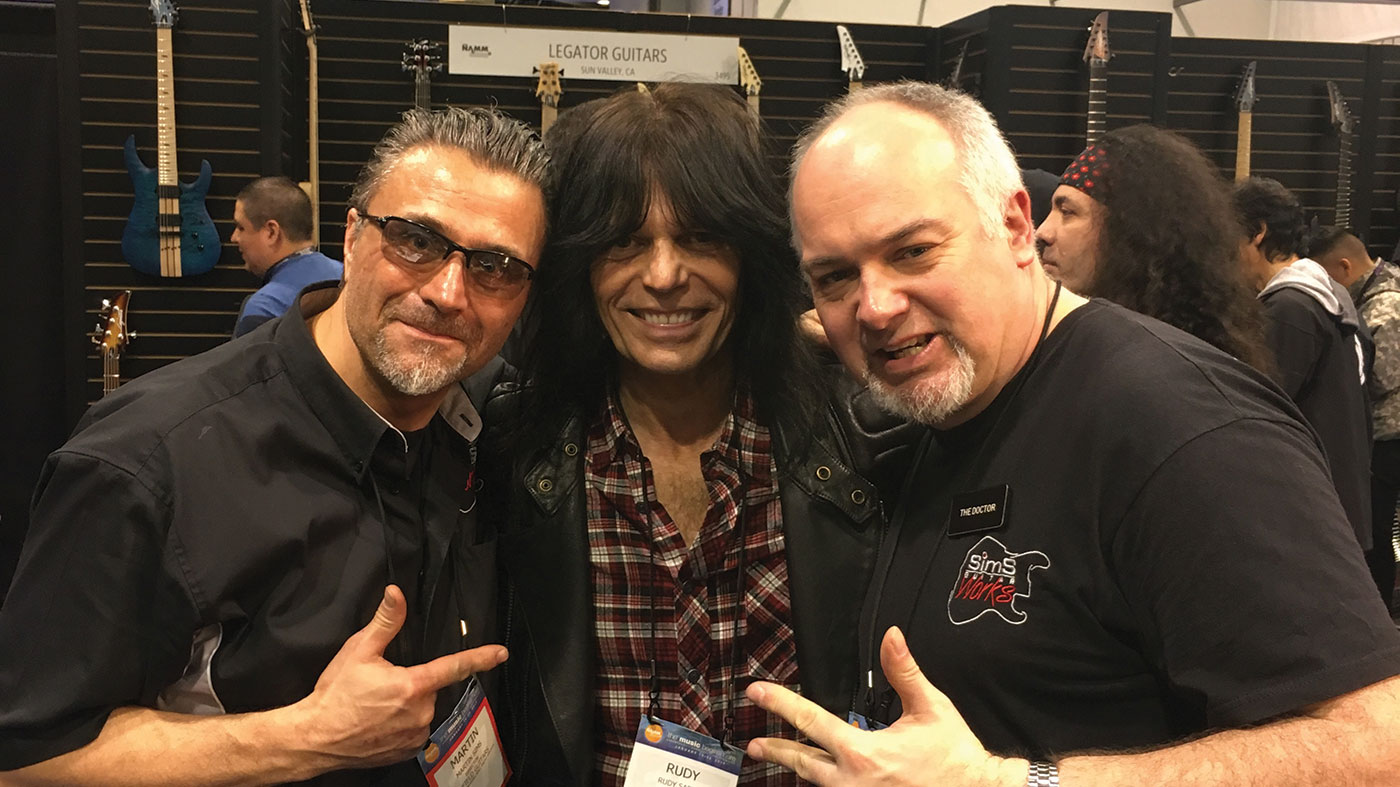

“I play Spector basses. When Spector asked me to design my signature Euro4 LX, I didn’t just want there to be a cosmetic difference between my model and the other signature models. I was walking around NAMM, and a friend of mine grabbed me and said, ‘You’ve got to check out these basses.’ They were Martin Sims’ Lionheart basses. I saw the Sims Super Quad pickups on them, and I was completely blown away - and I thought, ‘This is what I’m looking for. I’ll add them to my signature model to make them different from all the other Spector basses.’

“I’m blown away by the whole diversity of the instrument, to be able to have pickups with so many combinations, from split humbucker, single coil, and double pickups, and have it use the preamp or bypass the preamp. It’s just an incredible combination.”

Gear for the years

Do you have a preferred setting for those pickups?

“No, no. It all depends. I hear a sound in my head, and if I want a Jazz tone, say, then I go for the two single coils. If I’m going for a Precision tone, I just use one pickup, because the way that I have them is with a blend. I just blend it over to the split coil pickup in the front, which basically shuts off the bridge pickup.”

Are you equally happy with five strings as well as four?

“I play four, I play five, and I also play six. They’re all tools for the job, you know. I mean, you can’t show up for a job with just a Phillips screwdriver.”

Which other endorsement deals do you have?

As soon as I started playing through the wireless unit, I noticed that my tone really changed. I was getting a certain compression

“Oh, I need to go down my pedalboard... Ampeg, D’Addario, Ultimate Ears In Ears, Boss, J Rockett Audio and TC Electronic. Sometimes I need a compressor, sometimes I need a chorus. The TonePrint technology is phenomenal. I also recently started using what is called the SoloDallas Storm, and I’ve got to give you a little story about that. When I first started playing with Ozzy back in 1981, I inherited three of the original Schaffer-Vega wireless units that used to belong to ELO, the band, because Jet Records was not only the label for ELO as well as Ozzy, but also management. These three wireless units were probably built in the late 70s.

“As soon as I started playing through the wireless unit, I noticed that my tone really changed. I was getting a certain compression coming out of the unit. And because I don’t play with a pick, it really added definition to my playing without me realising what was going on.”

That is weird.

“All I knew was that I was playing through these wireless units, and my tone had the best definition I’d ever had! As time went by, those UHF or VHF frequencies in those units became illegal; just like in Spinal Tap, once in a while I would get some interference from planes landing while I was playing. So I put those to one side and they were just sitting on my shelf until recently.

“But then I played a charity gig not long ago, where we went through the whole AC/DC catalogue, and it turned out that part of Angus Young’s guitar sound is that wireless unit. I met Filipe Olivieri, who owns the company SoloDallas, which manufactures replicas of those wireless units in conjunction with Ken Schaffer. One of them is actually a pedal called the Storm, which Filipe gave me - and my tone is right back to what I had in 1981. It’s just unbelievable!”

You also have a line of acoustic basses with Sawtooth. What makes them a Sarzo bass?

“I’d always wanted to create an acoustic bass that would feel as if it had the tension of an electric bass, with 24 frets and a 34” scale. It’s pretty much like a regular electric bass, with a beautiful body; it’s all flame maple except for the ebony fingerboard. It comes with the brand-new Fishman preamp.”

You must have built up quite a collection of basses over the years.

“Yeah. I’m more of a keeper now than I was back in the day. I’m collecting more tools, because I do a lot of recording for different projects and various styles of music. If somebody calls me up and says, ‘I need you to use this particular instrument because this is what I want it to sound like on the track,’ then instead of having to go and borrow it from a friend, I already have it in my collection.”

Always on my mind

Is there some old stuff in there?

“I have a ’59 Precision. It’s just beautiful. It’s a slab fretboard, and the pickups are a little bit… what can I say? It’s a ’59, it’s almost as old as I am! But I’ve got to tell you, this Storm pedal brings it right up to spec. It really does.”

How about amps?

“I have a few, but for recording, I go straight, and I always leave a DI track that can be reamped, so I also send that to the engineer that’s working on a project.”

Are you still improving as a bass player?

The bass is always in my hands. When I’m on tour, it sleeps next to me, in bed - because I keep playing until I’m too tired to play

“Oh my God, yeah - which is a problem, because I hear my old recordings and I go, ‘I wish I could re-record this now!’ It’s a journey, though. I play more bass now than I ever have. The bass is always in my hands. When I’m on tour, it sleeps next to me, in bed - because I keep playing until I’m too tired to play, then I just lay it down next to me, and then I wake up in the morning and pick it up again.”

You were a guitar player first, right?

“Yes, I started playing guitar when I was living in New Jersey, but I wasn’t much of a chord player. I would play melodies on the guitar, which made easier to go from playing the guitar melodically to playing the bass, especially in the era when Paul McCartney and James Jamerson were all over the radio. All the bass playing you heard at the time was quite melodic.”

Why did you switch from guitar to bass?

“When we moved from New Jersey to Miami, I must have been around 16, not even 17 yet. I went to the band that was rehearsing in the garage on my block, introduced myself and told the guys, ‘I play guitar, I want to join your band.’ They said, ‘Well, we’ve got too many guitar players. Can you play the bass?’ I really wanted to join the band, so I said, ‘Oh God, okay…’ and they talked me into it. The guy said, ‘Listen, playing the bass is just like playing a solo during the whole song’. That’s the way he put it, and I thought, ‘That sounds good...’”

What was your first bass?

“My first original four-string was a Kingston bass. I sold it to a kid in Miami and then I bought a Gibson EB. Mine was just a single pickup model with volume and tone. It was headstock-heavy, so I got rid of it, and my next bass was a Rickenbacker. I showed a photo of it at NAMM to the person that now owns Rickenbacker, and he said, ‘Oh man, that bass is worth about $10,000 now.’ And I said, ‘Oh well. Who knew?’”

12 notes

What did being a guitarist bring to your bass playing?

“It’s the old Eddie Van Halen quote of ‘You’ve got 12 notes. Do whatever you want with them.’ It was about getting outside of that diatonic box, especially in the '80s, man. The '60s and '70s were more melodic, more outside the box, and harmonically richer than the '80s. I got to play a lot of those diatonic songs, and some of them were really big hits.

“As a matter of fact, I’ve looked back and transcribed the early Ozzy stuff, because I said, ‘Let me really analyse what we were playing back then.’ I looked at the Blizzard Of Ozz record (1980) and I went, ‘Wow, most of the compositions that Randy did with Ozzy on this record were very intelligently diatonic compositions.’ If you break down Mr. Crowley, it’s all D minor, F Major. Every chord in all the modes of F Major was applied to that song, and it was really smart the way it was done. It wasn’t like a pop hit. It was very dark and broody; Randy utilised all that.

Back then, if you were from the Sunset Strip, you weren’t really labelled as a metal band. You were just a rock band

“Now, he did the same thing with Goodbye To Romance, which is a very pretty, beautiful song in D Major. And then, by the time he got to Diary Of A Madman (1981), he broke away from that. He started using parallel modes in his compositions. That was the shift right there. But it only happened on Diary, because Randy passed away and he didn’t get to make another Ozzy record.”

I really enjoyed your book, Off The Rails. The late-'70s in Hollywood sound like an amazing era.

“Oh, thank you. Back then, if you were from the Sunset Strip, you weren’t really labelled as a metal band. You were just a rock band - hard rock, like Van Halen. By the time that I joined Quiet Riot in ’78, we were going through the rock versus new wave and punk period. As I learned when I joined Ozzy and started spending time in England, bands like Iron Maiden, Saxon, Motörhead, and so on were already making their statement in the late 70s in England, whereas that was not really the case in Los Angeles.”

You got very well-known with Quiet Riot.

“When I rejoined what was known as the Metal Health version of Quiet Riot, nobody thought we were going to achieve anything. We were just going to be another dinosaur band putting out a record. That’s the way that we were treated by the local industry, and fortunately MTV came along and we did a couple of videos and [QR’s 1983 cover of Slade’s ’73 song] Cum On Feel The Noize became a hit.”

What were the basses you were playing back then?

“Washburn and Music Man, and I also carried with me a practice bass, which happened to be a Roland GR. You remember the first Roland synthesiser bass? You could actually go through a big synthesiser, or you could go out analogue and use the pickup.”

What happened to that really cool black-and-white Washburn you had?

“It’s somewhere in Japan. I sold it to a Japanese collector back in the '90s. I look back and I think I should have kept it, but we entered the grunge period in the '90s and that was not a grunge bass, if you know what I mean. It had a certain tone, with original Bill Bartolini handwired pickups. Bill used to wire everything for me personally, so it’s definitely a collectable. Actually, I used that bass on Speak Of The Devil (1982), Ozzy’s re-recordings of Black Sabbath songs.”

Rhoads scholar

I always wondered how you approached Geezer Butler’s bass parts on those Sabbath songs. Did you deliver them as they were originally, or did you add your own spin?

“I played exactly what was on the records, which was very challenging because there were a lot of really cool riffs that are very exclusive. It’s a very original style of playing, very stylised, so when I played on the record I was just trying to do justice to Geezer’s blueprint of what the song is.”

What kind of guy was Randy Rhoads?

“My God. That’s the million-dollar question. That is the number one question I get asked when I travel, and that’s why I wrote Off The Rails, just to answer that. I’ll put it this way: I can say what Randy means to me.

“If it wasn’t for Randy, I would have never had the career that I’ve had, because he trusted me. This was the scenario: Ozzy was about 10 days away from going on the road, and they were in Los Angeles looking for a bass player. Not only a person that could play those songs, because there were many qualified musicians who could do that, but they needed somebody they could trust.

“I had already worked with Randy in Quiet Riot, so he told Sharon, ‘Listen, Rudy is the perfect guy because he’s not going to be a bad influence on Ozzy. He looks good, he’s reliable, and he’s going to be somebody decent to hang with in the bus.’”

Randy knew you well, of course.

Randy trusted me. He put his reputation with Sharon and Ozzy on the line to bring me in

“He trusted me. He put his reputation with Sharon and Ozzy on the line to bring me in. That’s how I got in, because I had no track record. Ozzy and Sharon brought me in and I was able to build a career from that and I am eternally grateful both to them and to Randy. And then, in addition, I am thousand per cent convinced that Randy saved everybody in Ozzy’s tourbus, keeping the plane from crashing into us. It clipped the bus, but it did not crash [directly] into the bus, and if that had happened, we would all have perished along with Randy and the others in the plane.”

Jumping from one massive band to another, did you just slot right in with Whitesnake when you joined them in ’87?

“One of the blessings in my career is the fact that I get to play with musicians and bands that I am a fan of. That’s very rare, especially for some kid from Miami. I mean, who else can say that? Especially when you’re living in an area and a culture where the chances of that happening to you are zero!

“First of all, you’re not English. You’re not living in England. You’re not even American; at the time I wasn’t an American citizen yet. I was just an immigrant, a permanent resident, basically - a Cuban refugee that became an American citizen. So for me to go and play with Ozzy and with Tommy Aldridge, whose playing I loved in Black Oak Arkansas, and of course Randy in Quiet Riot... it was incredible.

“Now, one of the bands that supported Quiet Riot on the 1984 Condition Critical tour was Whitesnake. That’s how I got to know [Whitesnake members] David Coverdale and Neil Murray, and of course John Sykes and Cozy Powell. I recalled the last night of the tour, as we were saying our goodbyes, David gave me a hug and said, ‘Someday we’re going to play together.’ I had already given notice, even before we started the tour, to the members of Quiet Riot that it was going to be my last tour with the band. So I was wondering, ‘How does David know that I’m leaving?’

“At the end of the tour, as soon as I finished my commitment with Quiet Riot and was a free agent, I got a call from Whitesnake’s management, and we met. David and John were working in the south of France, writing the new record, and Tommy and I went into the office. I was witness to internal conflict within Whitesnake during that tour, and I thought that it would not be wise for me to leave one situation for another situation, so I passed on the opportunity to make a record.

“A couple of years later, in ’87, when David was ready for the 1987 record to be released and for the tour to start, I got the call to do the Still Of The Night video, along with [Whitesnake’s new guitarists] Vivian Campbell and Adrian Vandenberg. So we all met at that video shoot and it was instant chemistry. We were like, ‘Oh wow, if you’re doing this, I guess I’m doing this, too.’ The chemistry was right and it just felt perfect. It was a great combination of people.”

Million miles

You had a bass back then that I absolutely loved, an Aria Pro II.

“Yeah, it was a custom. I asked them to put Alembic pickups in some of them and Bartolinis in others. I really had to reshape my tone for Whitesnake, because it was the first time I ever played with two guitar players. Vivian was on my side of the stage, and his sound at the time was huge. It almost went into my bass frequency, so I had to really change my tone. I stayed with them for seven years. The last time I toured with Whitesnake was ’94.”

That’s a lot of air miles.

“Yeah, I know. I’m a million-miler on American Airlines.”

Do they give you anything when you reach a million?

“They gave me a little tag that I can put on my suitcase. That’s all I get. Not even preferred seating!”

You played Peavey basses for a long time.

My principle was, ‘Let’s put a professional instrument in the hands of beginners, because that instrument should inspire them to play’

“I was with Peavey up until Mike Powers, the master luthier that I worked with for so many years, passed away in 2013. I’m very proud of the Sarzo basses. They’ve gotten so many great reviews, all five-star reviews. When I sat down with them to design the bass, we did it from headstock to tail. I told them, ‘Let’s give the customer their money’s worth. Let’s design something that should be worth about $1500 but sell it for less than $1000. The market does not need another $1500 bass.’ I was thinking about my first real working bass, a Jazz that I bought in ’67 for maybe $300 or $400. My principle was, ‘Let’s put a professional instrument in the hands of beginners, because that instrument should inspire them to play.’”

What advice can you give kids buying their first bass?

“I do these regular events called Rock And Roll Fantasy Camps, and we get a lot of beginners. They come to me with their instruments and say, ‘Can you tune my bass?’ or whatever, and I pick it up and the action is horrible, the tone, everything. They just don’t know any better; they think this is the way it should be.

“So I wind up tweaking their basses, lowering the action, getting the intonation right, spending about half an hour fixing it for them. Then I talk to their parents and I say, ‘I know that you don’t know if your son or daughter is going to stick with playing this instrument, but try to give them something that inspires them to get up every morning and want to improve and learn. That’s the most important thing’.”

Any tips for readers who would like to make a career as a bass player?

“I would say that the key element to a sustained career would be trust. That is something that you can only build by experience, from gig to gig. When I first started playing, I did not foresee my career as a journeyman. I wanted to be in one band, and one band only, for the rest of my career, and I can trace back the reason why I’ve gone from band to band.

“Randy passed away and I did not know how to deal with that. I did not realise, back in 1982 when Randy passed, that I, along with everybody else, was supposed to celebrate his legacy by playing his music. I ran away from it, because it was such a devastating, traumatic experience. Nowadays I understand the importance of that.”

First call

You were just a young man at the time.

“And we were traumatised. We still are. You can ask Ozzy, Sharon, Tommy, Don Airey, all the people that were there to experience it. We’ve never been the same. So we just learn how to deal with it and make the best of life. Getting back to trust, don’t ever walk away from a gig, don’t ever do anything to get yourself fired.

Be the first guy that everybody’s going to call because they know that you’re going to be professional

“Be the first guy that everybody’s going to call because they know that you’re going to be professional, you’re going to learn the songs, and you’re going to add something to the band that would help them get to the next level. And I’m just being superficial here; I’m not even getting in deep, because I can spend hours talking about the importance of this.

“The other important thing is to learn. Learn, learn, learn. It’s always about improving. A musician never stops learning and progressing. And never set limitations. I’ve come to the realisation that I’m never going to be the bass player that I aspire to be, because I really don’t want to do that. I never want to get to the point that I say, ‘Okay, I’m done. I’ve learned everything I wanted to learn.’ No, never! There’s so much more to learn, to expand on your knowledge.”

What mindset do you need to join a band?

“Be as professional as possible. Remember, when you join the band, the band is not joining you. I’ve worked with so many incredible musicians who, when they join a band, do not take into account the legacy of that band. It’s not just about your own personal contribution. It’s about learning the catalogue the way it was originally recorded, and then listening to current versions of how the group is playing it.

“Of course they expect you to add your own personality, but don’t change what you’re doing so much in reference to the original that the audience is not going to recognise the song any more. Especially in a legacy band, there are certain melodies and moments within the songs that the audience expects.

A lot of musicians think of music as a job, but of course it’s bigger than that.

“It is way bigger than that. I think I can say this for every musician: we were fans before we were professional musicians. And we must always remain fans of music, of what we do, of the bands that we play with, and of the legacy of the bands.

“At the end of the day, we musicians who are in legacy bands playing catalogues, we are memory merchants. The audience comes to watch our show to reconnect with a certain moment in time, and we bring that joy to them again. It’s a celebration, what we do on stage.”