"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

Best of 2024: As Purple Rain celebrates its 40th anniversary, we put one of Prince's best-loved songs under the musical microscope

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2024: Purple Rain turns 40 years old this year, so to commemorate this occasion, I’m taking a look at the first single from its mind-boggling soundtrack.

It’s also the first of Prince’s string of Billboard Number Ones. The single version is embedded above, with its iconic video, but the album version is longer - and better - and that’s the version I’m going to dig into in this article.

This is an extraordinary recording, because the “song” occupies only about half its length. After the last chorus, there’s a synth and drum machine groove, then a long guitar solo, then another synth and drum machine groove, then a different synth and drum machine groove, then a synth solo, then yet another synth and drum machine groove, and finally a coda that reprises the synth solo. This isn’t a song, it’s an epic sonic adventure.

When Doves Cry was the last tune that Prince wrote for Purple Rain. Director Albert Magnoli asked him to come up with something for the montage scene where the Kid is riding around on his motorcycle, having just lost his girlfriend to Morris Day. Prince wrote When Doves Cry that night. On March 1st, 1984, he started production on it in Los Angeles’ Sunset Sound studios. That first session was just two hours long, and he didn’t record anything; he probably just programmed drums and chose synth sounds.

The next day, Prince went back into Sunset Sound and finished the entire rest of the track in a single marathon session sprint. The only other person present was engineer Peggy McCreary. They worked from 3:30 PM until 7:30 AM the next day. I hope McCreary was getting overtime! She talks about the session in this interview.

In the small hours of the morning, McCreary bounced a rough mix to cassette so Prince could listen to it in his car. He drove to Wendy and Lisa Melvoin’s house to play it for them and whichever friends of theirs happened to be there. (Prince must have had a very different relationship with his friends than I do with mine.) He was feeling ambivalent about his bassline. Here’s a speculative recreation of it:

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Prince was considering removing the bassline from the song entirely. Singer Jill Jones encouraged him to follow his instinct. He went back to the studio to resume work. McCreary describes how the track had become too grandiose, so Prince started stripping out layers, a process that McCreary calls “unproducing”. His last step was to mute the bass.

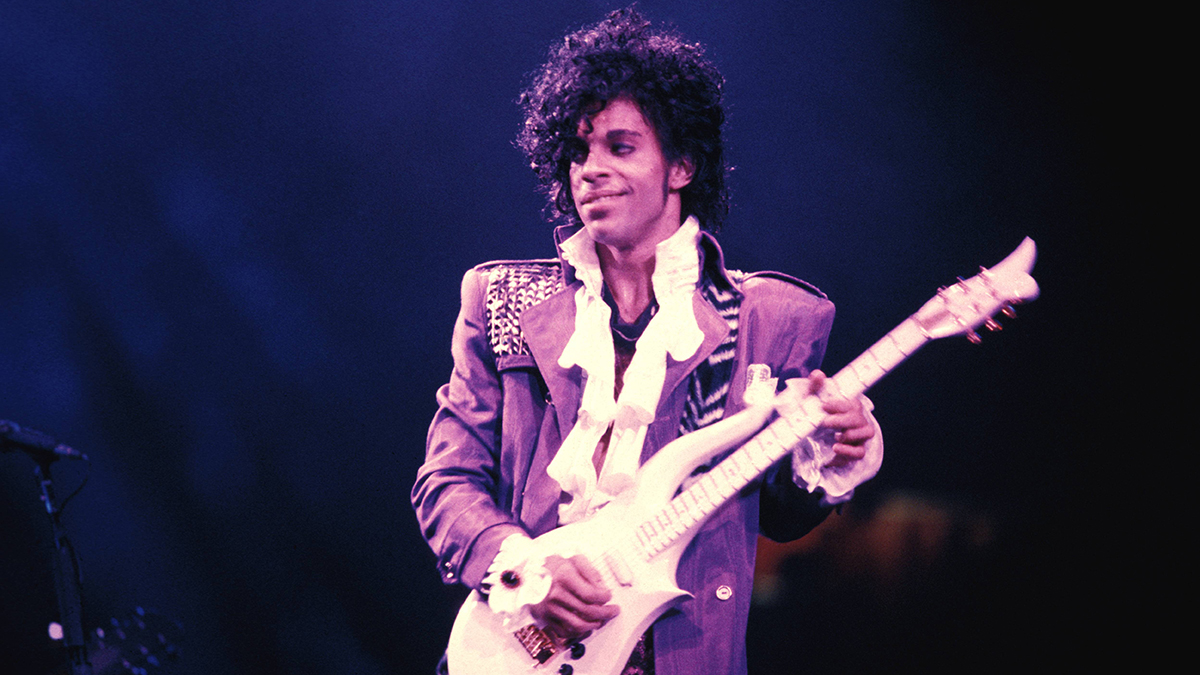

Prince is such a dazzling talent as a singer, songwriter and dancer that it’s easy to forget that he may also have been the best rock guitarist in the world. It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognize his guitar virtuosity. In a 1994 Guitar Player interview, he said, “I always wanted to be thought of as a guitarist, but you have a hit and you know what happens...” This might be one reason why When Doves Cry devotes so much space to his shredding. The guitar gets its cutting tone from a Boss OC-2 octave divider.

Prince played the synth parts on a Yamaha DX-7 and an Oberheim OB-X. He had the baroque synth solo planned out in his head, but he had to slow the tape down so he could play it at a more manageable tempo. Beyond the practical necessity, this move had a sonic benefit: speeding the tape back up gave the synth an unearthly timbre due to its harmonics being squeezed together.

The famous drum machine part has Prince’s characteristic knocking sound, which he made it with his beloved Linn LM-1. Here’s a recreation of the beat; it starts at 4:10.

The drum pattern is two measures long; you could think of the first measure as a call and the second half as a response. The most important feature of the pattern is the empty space on beat three in the response measure. This is the strongest beat in the bar aside from the downbeat, and you naively expect there to be a loud accent there.

In the first bar’s beat three, there’s a quiet tom hit, not the accent you were expecting, but at least it’s something. In the second bar, beat three is completely empty. That silence has a strong presence of its own, and it’s attention-grabbing every time.

The LM-1 had two features that Prince especially loved. First, each sound (kick, snare, hi-hat and so on) had its own output, so it was easy to process and mix them independently. Prince liked to put different drum sounds through different guitar pedals to find new and distinct timbres.

The LM-1’s other key feature was that it had a separate tuning knob for each sound. The famous knock is a pitched-down cross stick snare hit. On an acoustic drum set, you make this sound by putting the tip of the stick onto the drum head and slapping the body of the stick against the rim. This creates a staccato “tick” sound. Prince tuned the LM-1’s cross stick sample down by more than an octave and ran the output through a Boss flanger pedal, transforming the tick into a spacey knock.

The LM-1 was created by drum machine innovator Roger Linn. In this interview on Minnesota Public Radio, Linn says that he never got to meet Prince in person, but he was delighted by the central role that the LM-1 played in his music. The ability to tune all the drum sounds independently contributed to the machine’s hefty price tag, and Linn removed that feature from later models to bring the cost down.

This is why Prince stuck with the original model. He didn’t just like the tuning; he also praised the timing and feel of the machine. The clock inside the LM-1 used a crystal, and as it heated up, the tempos would speed up a little. The tempo doesn’t drift at all in When Doves Cry, it stays locked in at 126.46 BPM, but maybe it started out at an even 126.

There is one mystery sound in the track: the robotic-sounding vocal right at the beginning. Is Prince running his voice through a talk box or vocoder? A Twitter friend of mine thinks that it’s an Eventide H3000 Ultra Harmonizer, which has some vocoder-like settings. That sounds plausible to me.

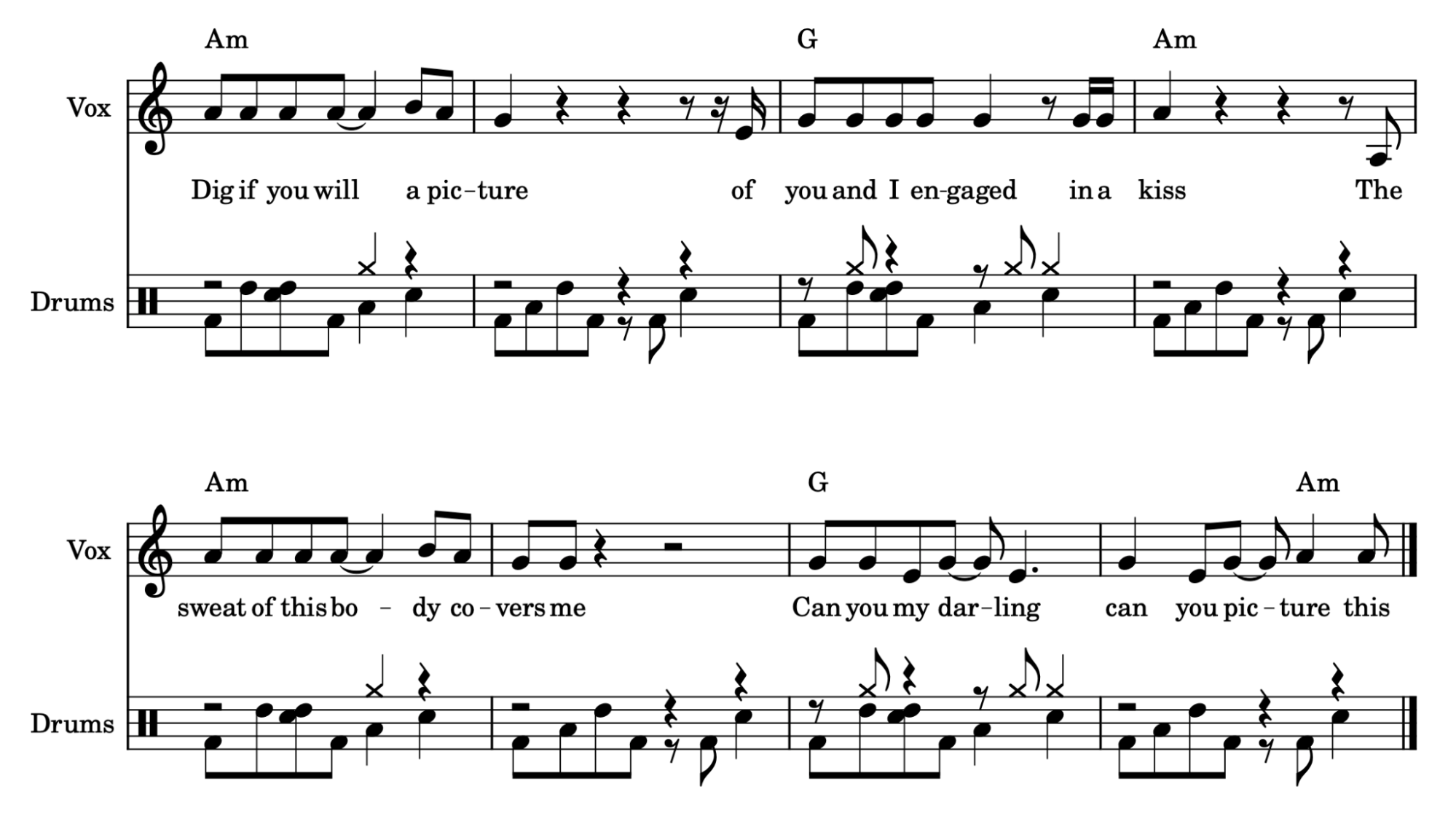

When Doves Cry is harmonically and melodically minimalist to the extreme. The first verse has no chords underneath it, but the vocal melody implies Am and G. Notice that the harmonic rhythm is different on the first and second lines. In measure four, the implicit Am chord falls on the downbeat, on the word “kiss.” In measure eight, however, the Am chord is delayed, falling on the “and” of three, on the second syllable of “picture.”

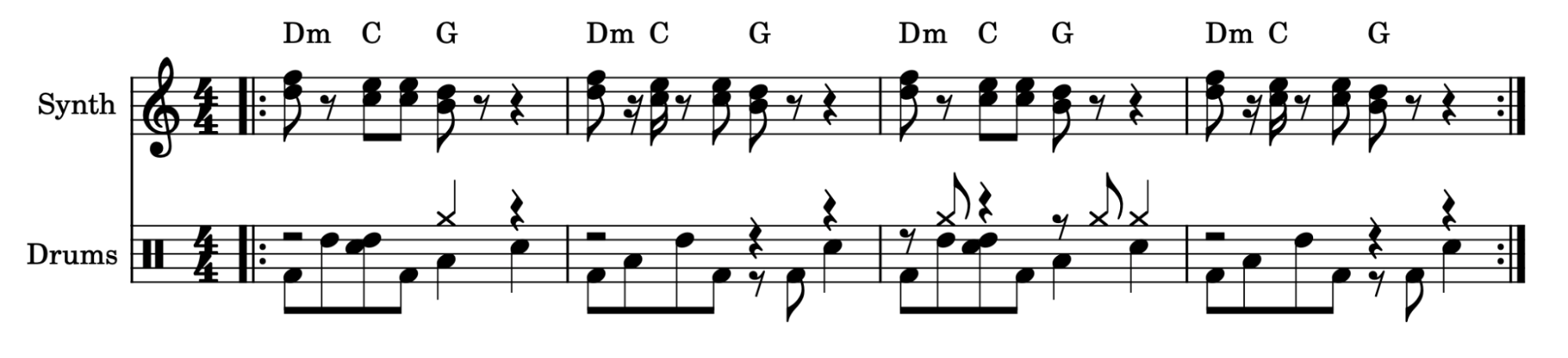

The synth riff from the intro uses Dm, C and G chords. The first time through the riff, each chord falls squarely on an eighth note. The second time through the riff, the first C chord is anticipated by a sixteenth note, putting it on an exceptionally weak subdivision. That attention to detail is what makes a Prince song sound so unlike standard 80s pop, even when he is using the same synth patches as everyone else.

The synth riff reappears after each chorus. After the guitar solo, Prince brings it back again, and accompanies it with some synth strings playing a different chord progression entirely: Am, F, G, F, E. Most of the notes in the intro riff happen to mesh with those chords, but some of them conflict. Check out the second bar: it ends with B and D on top of an F chord, a bold and unconventional combination.

I don’t talk much about the lyrics of the songs featured in this column, because other people have usually already written so much about them. But I couldn’t let the lyrics to When Doves Cry go without comment. They are sublimely odd! In his column The Number Ones, Tom Breihan describes the song as “opaque poetry, a hallucinatory swirl of panting come-ons and animal imagery. That means it’s classic Prince — half functional, half mysterious, able to do its work while still leaving your mind spinning.” I couldn’t put it any better.

If you want to cover When Doves Cry (and many people have), there are two problems you need to solve

Consider the opening line of the song: “Dig, if you will, a picture.” In the first four words, Prince manages to combine jazz slang with a flowery Victorian-ism. The language stays strangely formal, even when it’s describing physical love: “engaged in a kiss”, “the sweat of your body.” Not “my” body, “your” body! And who sings so much about their parents in a sweaty love song? Only an incomparable genius.

If you want to cover When Doves Cry (and many people have), there are two problems you need to solve. First, you have to decide whether you are going to just do the verses and choruses, or attempt anything from the other three minutes of the track. Second, you need to figure out what to do about all the places where the end of one line overlaps the beginning of the next one. There are three of these spots:

- Between the two halves of verse one–“can you picture this/dream if you can a courtyard”

- Going from the first verse to the first chorus–“in between me and you/how can you just leave me standing”

- Going from the second verse to the second chorus–“even doves that cry/how could you just leave me standing”

In his concerts, Prince handled these overlaps by giving some lines to the backup singers. But what if you want to sing your cover solo? Most people just swallow a word or two. It can sound awkward, but that hasn’t stopped artists from every style and genre from trying. Below, I list a few noteworthy versions.

Patti Smith does the song as a slow and sultry rock groove.

Ginuwine’s cover is backed by a great Timbaland beat, which uses the drum break from Fool Yourself by Little Feat for extra intertextuality.

Quindon Tarver’s version from the soundtrack to Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet begins with a nice choral arrangement.

Bob Belden gives the tune a jazz/funk treatment, with vocals by the great Cassandra Wilson.

Kirk Hammett and Robert Trujillo of Metallica do the song as a goof during a show in Minneapolis.

My favourite cover is the bluegrass version by Sarah Jarosz, which showcases her impressive mandolin chops.

Many hip-hop and dance producers have probably wanted to take a crack at When Doves Cry, but Prince (almost) always refused to license samples. When Audio Two included a slowed-down sample of him singing “this is what it sounds like” in their track Make It Funky, they had no permission whatsoever.

Early rap didn’t have much of a cultural footprint outside of certain neighborhoods in certain cities, though, so it was easy for this kind of thing to fly under the radar. Rather weirdly, Prince did give permission to MC Hammer, of all people, to sample the beat from When Doves Cry for his underwhelming song Pray.

Interpolating and quoting Prince is much less legally problematic. Bizzy Bone quotes When Doves Cry on Thugz Cry, and another Bone Thugs-N-Harmony member, Krayzie Bone, also interpolates the song on Can’t Get Out The Game.

You need permission to sample a recording, but anyone can record or perform a cover as long as they pay the statutory license fee to the songwriter. But what even is the song we are talking about? You will notice that none of the covers listed above even attempt to include the second half of the album version. Is all of that stuff even really part of the song at all?

In his book The Poetics of Rock, Albin Zak distinguishes between songs and tracks. A song is a musical composition, while a track is the realization of that composition in a recording. Bob Dylan wrote the song All Along The Watchtower, but it exists in most people’s minds as the track recorded by Jimi Hendrix. With that distinction in mind, think about When Doves Cry. How much of the album version is the song, and how much is the track?

At a minimum, people treat the song as the two verses, each followed by a chorus, surrounded by varying amounts of groove in A minor. More ambitious covers include the synth riff from the intro, and maybe they end with some kind of extended groove at the end. As far as I know, no one other than Prince himself has ever attempted to play the full album version. How could you? And, given the perfection of the track, why even would you?

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.