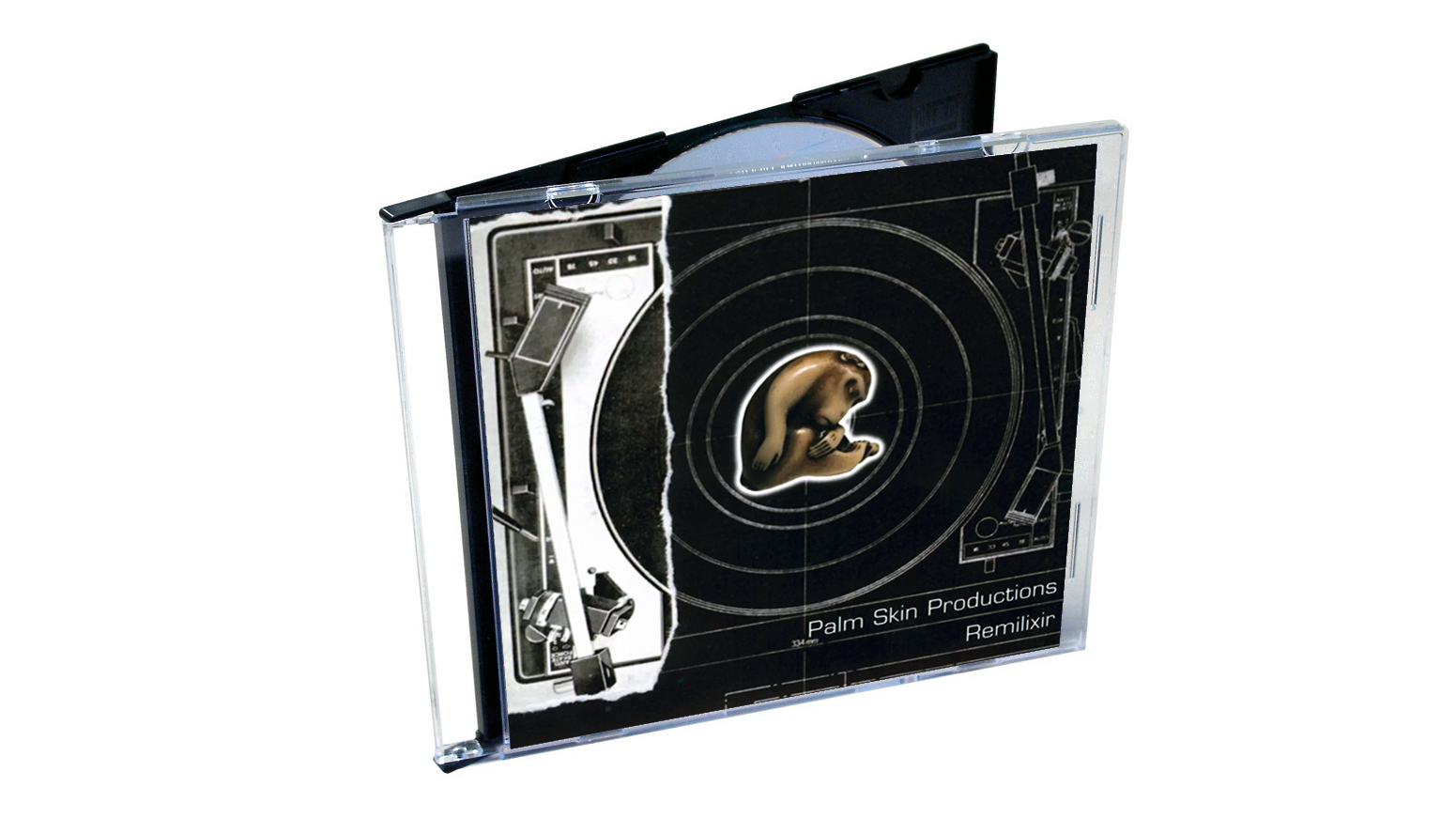

Palm Skin Productions on Remilixir: "Virgin were hoping for a Daft Punk record, but what I thought was, ‘Now I’ve got a chance to go really deep!’ That’s how you get dropped after one album"

Fresh from Mo' Wax and signed to Virgin, Simon Richmond plundered the major-label coffers to produce his most daring release yet. Here's how the album was made

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After a string of killer singles and EPs helped turn Mo’ Wax into one of the coolest record labels in the UK, the name Palm Skin Productions was on everyone’s lips.

His brand of flipped funk, smooth acid-jazzed beats, deft sampling and hip-hop chops, was defining a new wave of underground music in London. And, inevitably, the majors came sniffing, looking to poach a credible electronic act of their own.

The Goliath with the meatiest chequebook was Virgin, who promptly signed the man behind the moniker, Simon Richmond, and threw him the keys to the plushest recording studios in town.

Obviously, they wanted a hit dance record. He had other plans. “I think that Virgin were hoping for a Daft Punk or Chemical Brothers record,” says Richmond. “And, probably, my first release on a big label should have been something more banging and crowd-pleasing. But, what I thought was, ‘Now I’ve got a chance to go really deep!’. And that’s how you get dropped after one album [laughs].”

It really was a privilege to be able to have any idea, and then make it happen

Although not the radio smash a major label demands, Palm Skin Production’s Remilixir is a classic of the era. Building on the groove and late-night future jazz of his early Mo’ Wax tracks, he added in more abstract beats, lusher instrumentation, and increasingly dense and moody synthscapes. All topped off with his live Rhodes and percussion, guest turns, and some experimental production techniques, for added texture.

“There were constant non-rhythmical samples running in the background, looped up,” he says. “And field recordings played at the wrong speed on tape. And what really drove me was eking out harmonic content from non-harmonic sources. So, a weird squeak or a noise or scratch became a melody. All that was going into

the mix.”

And, with Virgin’s bottomless coffers to plunder, he could indulge any musical whim. “I could say, ‘I’d like to hire a vast rack of Zildjian cymbals, please’. And I’d try them out for the morning. It really was a privilege to be able to have any idea, and then make it happen. That really made this record so special.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“The album was finished up in various Matrix Studios in London. And some stuff at Milo. And mastered at Metropolis.

“It was just great to be in a room with an engineer. I didn’t realise quite what heroes they were. You just turned up and said, ‘I’m not sure how to do this, can you do this?’.

“I had an Atari 1040 with about 2 Meg… I think I had 4 Meg, eventually. And it had the little dongle, so you could connect it to SMPTE. Then I had a pile of synths and stuff, like a Korg Mono/Poly, MS-10, Yamaha CS-5, Korg Delta. A Space Echo, Ursa Major Space Station, Roland JX-3P, a Lovetone FX pedal. And I used an Eventide, Theremin, and my Rhodes.

“My sampler was an Akai S1000, on floppies, running off the Atari. With the Cubase crack that everyone had. I don’t think I met anyone back then that bought a copy. Then lots of percussion, as I started a percussionist. And a record deck and Vestax PMC-06 mixer.”

“I was learning stuff everyday at these studios. The album was mastered by Tim Young from Metropolis. He taught me to knock the sub out the stereo image, to make sure your sub is as mono as it can be. Then, when it comes to your final mix EQ, taking it out of the sides, and leaving it up the middle. That suddenly opens everything up. And, it’s warmer as well. And eats up less space in the stereo. It was that era, having that privilege and time to hang out in studios with all that gear and those guys. That taught me a lot.”

Remilixir track-by-track with Simon Richmond

Condition Red

“This features Yuka Ikushima. I met her through doing stuff with Howie B and Toshi and Kudo from Major Force. I got the backing music together, got her in the studio, and just told her to do her thing. I remember distinctly that it was a case of getting the engineer out of the room, and just recording without her worrying. Because, it wasn’t formed. And she was used to being a session singer, and knowing exactly what she was needed to do.

“I also discovered that I liked the sound of putting a snare through an old Maestro ring mod from the ’70s. It cropped up a fair bit on everything I did.”

Fair Seven

“There’s a fair bit of me scratching on here. It’s part of an actual live dialogue between Chris [Bowden] on sax and me on the decks, swapping bars. I’ve worked with him since the Mo’ Wax days.

“Chris’ sax goes through a Lovetone FX pedal. And they were beautiful. From the same era as the Sherman Filterbank. There were vibratos and filters and ring mods on there. And I chucked Chris’ sax through everything, and tried it out.

“What was great about being in a studio with a proper desk was that you could crosspatch everything. So, you could record him dry. Then put him through ten channels. It was such a beautiful luxury, and how it should be with music, really.”

How The West Was Won

“This, for me, is a really romantic piece. And, it was a kind of love song between a Chinese zheng, which is like a stringed instrument, and a turntable. I suppose it was a slightly crass juxtaposition of this kind of Asian traditional sound, with gritty beats from a battle record.

“I think 99% of the beats and the rhythm – and in fact, everything that isn’t the zheng – I was scratching in live to tape, rather than sequencing it. I think there might be one hi-hat that I sequenced, maybe, to keep it tight. Then there’s a really sweet little Rhodes turnaround in it. I’m so happy with that, because it stops it being totally random. It stops it being just noise and a topline.”

Osaka

“I think this was one we recorded at Milo. I’d written it in about ’93. Because there was a Straight No Chaser tour in Japan with me and, you might say, a supergroup [of jazz heads]. And this tune was written to play in Osaka. I didn’t get a chance to record it, then. And before I signed to Virgin, I’d begun an initial sniff of a Palm Skin album for Mo’ Wax, and Howie B engineered this [later] session.

“I ended up with the two-inch, so re-used that, and re-recorded various bits and bobs, because I think the original had live drums on it, whereas this album version has programmed drums.

“Neil Yates on trumpet, too. He’s just a phenomenal, phenomenal player. Absolutely amazing.”

Trouble Rides a Fast Horse

“I just wanted this one to sound like a bit of film music. Like, classic Lalo Schifrin. That kind of moody thriller-ish kind of thing. And that’s what it does.

“I did that one mostly at home. The fuzz stuff and wah wah stuff was all recorded to cassette, which was bounced to two-inch.

“And the drums are all cut up from a drum solo from one of those Mood Music albums. These days you’d record the audio into Logic, and then sit there looking at it. Back then, music wasn’t a visual medium. I really miss sitting at the desk, looking in the middle distance.

“Yeah, with this track it was all cut up with, you know, numbers

and alpha dials on an [Akai] S1000, then played in. Which is possibly stupid [laughs].”

Flipper

“I was also out in Spain at this time, working with Neneh Cherry on music, and playing with her live. I met David M. Allen over there, who’d worked with The Cure and Human League. And he had this amazing new thing called Pro Tools, which was this vast tower thing. I recorded 15 minutes of freeform stuff with my new Roland JX-3P, with its own sequencer, and a Yamaha CS-5, running independently, not synced.

“Back at Matrix, I recorded it to tape. Then set up some radically different effects chains with an Eventide and a series of gates.

“Then a couple of compressors, working on duck, so when you moved the fader the other effect kicked in. So, the whole thing is just working from one texture to the other.

“It was very wonky and weird. Then I overdubbed some Theremin and a bit of Rhodes.”

Introduction To Falling (Fragment)

“This is a fragment, and it’s a fragment of a tune called Falling. That was one I recorded at Milo. It was a live thing. There was a guy called Jim Carmichael on drums, who used to play for Freak Power and Adam Freeland.

“It was a sprawling track where I basically ripped off a bit of Steely Dan, then tried to make it sound like The Headhunters, without really knowing what I was doing.

“The beginning of the original tune had that introduction of me playing on the Rhodes. And that’s the part I decided I liked more than the rest of the tune, so used it on the album. Then I chucked some vinyl crackle sounds on it.”

New Love Games For Your Monkey

“I’d been listening to a cassette bought in the mid-’80s called 21st Century Dub, heavily featuring a Japanese percussionist called Pecker. I adored one of the tracks, and I realised it was a reversed conga.

“So, I started this by playing a big conga pattern, and then turned the tape over and bounced it in reverse to build everything from that.

“I was in a decently built studio, with a decent sound booth, with decent mics, and had the money to say, ‘Let’s hire cymbals. Let’s have a good engineer, so I don’t have to keep running backwards and forwards, trying to record myself...’

“Having a record deal like I had allowed me to have the luxury of money to spend on ideas like that.”

Meantime

“It’s got that long delay. And again, that one was very much already written. And a piece that was kind of quite fixed.

“So, Yuka came in again to sing, and she had the part, and she sang off a score, this time. Then, Jeremy Shaw has a tiny vocal.

“In my demo, I had sampled a George Benson version of a Beatles track. But, I got nervous and got Jeremy to re-sing that line again. It goes on for nearly seven minutes… These days, even I would probably say, ‘Let’s trim this a bit’. I mean, that said, when I got signed to Tru Thoughts last year, the first track they put out was 11 minutes long! [laughs]”

Kitty’s Adventures In Meat

“This was the peak of my collecting analogue keyboards and things. And I just wanted to try everything freeform to tape.

“So, there’s a Korg Mono/Poly, Yamaha CS-5, Korg MS-10, Korg Delta, Space Echo and an Ursa Major Space Station. I wanted to get into that Radiophonic Workshop type of thing.

“Then my girlfriend called the studio, and she was watching something in the background, and sang something from it. It sounded ridiculously uncanny with the music. And I said, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute. Can you sing that again?’ And we got the microphone and recorded it. She also had a thing about Hello Kitty. And I had this image of a girl walking into a dark wood of sound, and that’s what it turned into.”

Walking Through Water

“Yuka Ikushima again. I think she’s just doing a terrifying kind of banshee thing. Like, dying, gasping screams… Back in those days, I don’t think there was any Auto-Tune. I mean, if there was, it’s probably the kind of thing that Trevor Horn had.

“And you weren’t recording to a hard drive. You’re recording to two-inch. So, it was a question of takes, and things like that. I still really liked that. Just recording an honest version. In the background of this there’s a bell sound, clanking away. And I had this image of sailors drowning at sea. I wanted it to have the pace of a large ship going down.”

Beethoven Street

“That’s where I lived. It was on the corner of the Mozart Estate in northwest London, which was pretty hairy. It was very good for crack… and, then behind that was the back of the Bakerloo line. And there was this constant kind of noise going on. And, one evening while it was raining, I recorded it out the window and slowed it down. And it sounded like seashore. And that became the basis of the background for Beethoven Street.

“Gay-Yee Westerhoff played cello on it. At the time she was an incredibly shy goth, and an amazing musician. She went on to be the driving force in the classical girl band, Bond, and is living a large and an amazing life now.”

Visit Palm Skin Productions' website for all the latest on new and forthcoming material.