Marcus Miller: "I've always hated bass solos; that's the one point when the music isn't grooving any more"

The jazz and session veteran on the key to successful improvisation and how bass playing is changing

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

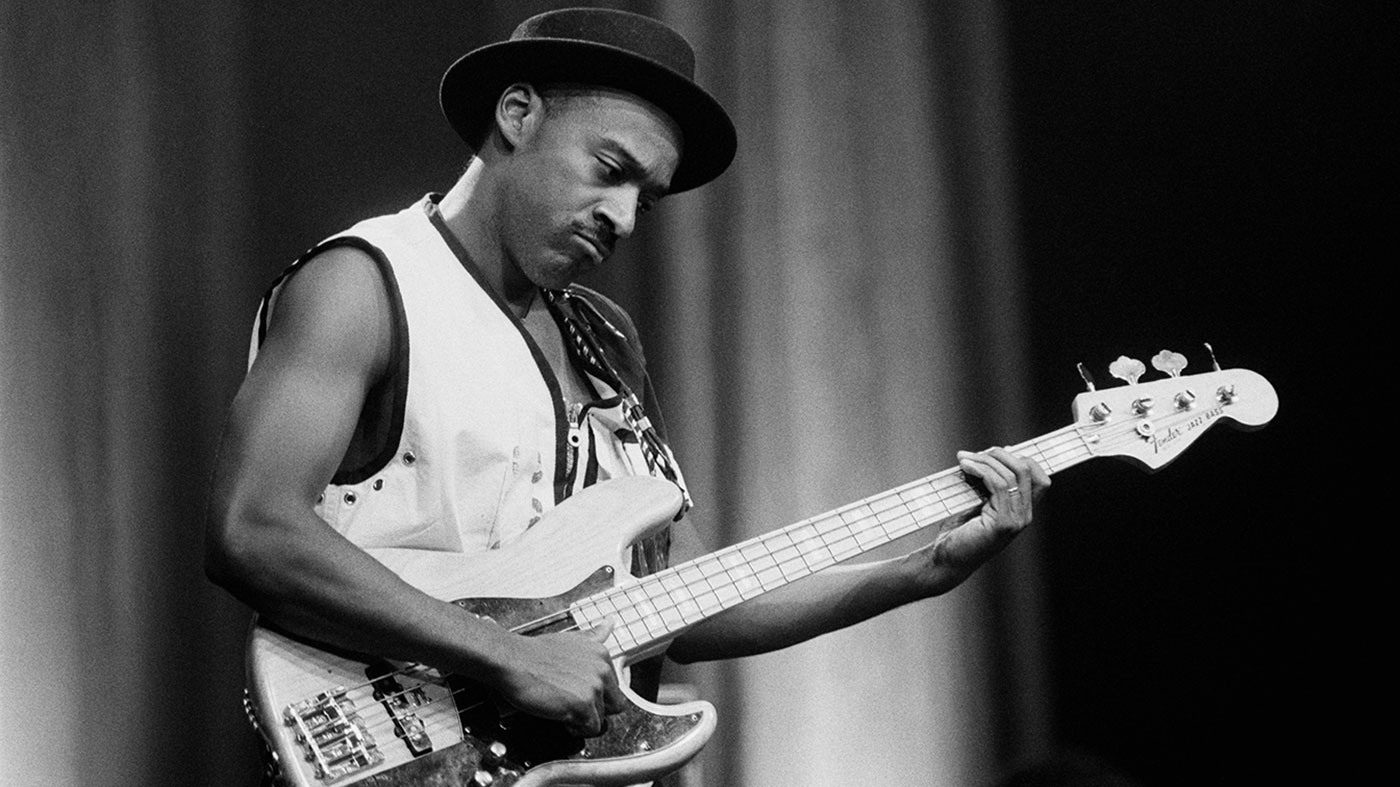

Miles Davis. Herbie Hancock. David Sanborn. Donald Fagen. Dizzy Gillespie. A whole host of film soundtracks and a string of awe-inspiring solo albums - what else is there to say about the great Marcus Miller?

We meet Marcus in London to talk about his new album, Laid Black, and to hear his words of bass wisdom, not least about gear. We start by enquiring about the new Sire basses to which Miller is giving his name. Why move from a high-end model to mass-produced instruments, we want to know?

I still have my Fender, which I’ve been playing since I was 17 years old, and I play my Sire fretless, and my Sire four-string

“I’ve had a Marcus Miller model Fender bass for 20 years,” he explains. “It’s time to do something else. Originally the Sire guys suggested an inexpensive student model, but eventually the project ballooned, and I had to make a decision. I’d been with Fender for a long time, and doing a Marcus Miller Squier model didn’t sound so exciting to me, so I decided to try this, not knowing that it would get so big.

“I still have my Fender, which I’ve been playing since I was 17 years old, and I play my Sire fretless, and my Sire four-string, which has a slightly different voice. For the solos on my album, in my opinion it actually speaks a little better, and has a little more sustain. My Fender Jazz is from 1977, and you have to really work hard to get it to sustain.”

Forget about selling the bass to ordinary people - we ask how Miller would persuade another star bassist, say Bootsy Collins, to try the Sire. “Bootsy obviously has his own sound with his Star Bass,” he replies, “but what I might say is that, at some point, he might want to have a Precision sound, or a Jazz sound, just for one song, and this is a great bass to have for that.”

Expensive habits

We note that, no matter what bass he’s playing, Miller always sounds very much like Miller. If he can do all that on a $500 bass, does the world need $5000 basses?

“There are certain things that expensive basses do really well. For a gear expert, I don’t think a Sire can compete with a $5,000 bass, mostly because of the quality of the components. But the sound is good. I think there is the need for both kinds of bass.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The Sire bass isn’t the only new collaboration Miller is involved with. There are also the bass amps he’s creating with Markbass; we’re curious to know how that happened. He starts by giving us some background on studio work.

We were doing sessions so fast that producers started recording us direct: to have more control, we all put preamps on the bass

“When I was a studio musician in New York, we were doing sessions so fast that producers started recording us direct. With no amp, our sound was really in the hands of the engineer: to have more control, we all put preamps on the bass, to shape the sound before it went to the desk.

“Later, in an interview, I said that I just wanted an amp that reproduces the sound of my bass with as little tone variation as possible. Marco De Virgiliis of Markbass read that, and decided to create such an amp. That’s how we got together. He approached me, although initially I wasn’t really digging the Markbass sound; there was a lot of bottom, very clear, but in the situations I play in, I need some bottom and some top. I might not use all the bottom or all the top, but I don’t want an amp that forces me to play in a certain way - I want to make that decision.

“Marco invited me to the factory and gave me a prototype cabinet with unusual characteristics. I played a few notes and there was a lot of booty there! However, the high end was still not clear. Nowadays, not a lot of bass players use bright, and I don’t use bright as much as I used to, but I still want it there, and I want to be able to control it. Marco and his buddies started holding up different tweeters while standing in front of me. I was going ‘Nah’, ‘Hmm…’, ‘Oh!’ That’s how we worked.”

He laughs. “On a traditional record, what the engineer is really looking for from you is the low mids. They want the bass to either sit just below the bass drum, or just above the bass drum. For the most part, the engineer has no need for you to be up there with the bright shiny stuff. So, consequently, the things you love about the bass, the deep low end and the crystal high end, are no help in recording. You do need the mid-range, which is the nastier sound among the bass frequencies. You need that to get mixed into. The fi rst times I was working on my records I used to hate it, so I played thumb style as another way to get clarity in the mix.”

Forget to remember

When we interview a musician who does session work, we’re keen to discover whether they remember what tracks they've played on.

“It’s easy to forget or be confused,” admits Miller. “As a session musician, your relationship is with the producers, not the artists, so you may not be familiar with the final result. Sometimes vocals are added later: for instance, I played on Just The Two Of Us by Bill Withers and Grover Washington Jr, when I was 19, and we cut it as just another instrumental Grover Washington Jr song. Then they called Bill Withers, he wrote the lyrics, and it became a huge hit. If [producer] Ralph MacDonald hadn’t told me, I’d have heard it on the radio and barely recognised it.”

He continues: “A lot of people know me for a certain sound, but as a studio musician, 60 to 70 percent of the bass playing I did was not with that sound, as it wasn’t appropriate. You have to sound like whatever’s needed for that song.”

Can Miller the session musician predict when he’s playing on someone’s next monster hit? He smiles. “Yes. You can hear it from the music, and if you know that the artist had a huge hit just last year, you know that there’s three million people waiting for the next record. Play good, because you’re gonna hear it for the rest of your life!”

Playing well is surely second nature to Miller, so we wonder if he still has to practise.

“Oh yeah, you can’t not do it. In the same way that, as an athlete, you can’t just say ‘Okay, I got it!’ and sit around. Without practice I can get through a gig, but then you find yourself not moving forward. The beautiful thing about music is that you always continue. I’m working on things that are more subtle, like clarity of ideas in improvisation. Being able to connect themes in your improvisations, make it sound almost like a composition in itself. Articulation, making sure that the right notes are accented in your line. And don’t just let the accents come where they’d naturally fall on your fingers. Try to add control, and be able to say what you want to say.”

Real-time

He makes it sound easy. “I do improvise, and make it up as I go along. But if you’re going to be the kind of musician who does that, you can’t just practise ‘a piece’ like a classical musician; you’ve got to practise everything, because you never know what you’ll want to do.

“There’s nothing worse than having an idea in your head and being unable to get it out in the moment, in real time. I try to play in phrases, especially as a bass player. My solos sometimes just exaggerate the bassline, and other times they’re more linear. In truth, I’ve always hated bass solos.”

Other bass players are digging bass solos, but for everybody else, that’s the one point when the music is not grooving any more

Wait, what? “Because the bass stops! Other bass players are digging it, but for everybody else, that’s the one point when the music is not grooving any more. I felt like that even when I was very young, and chose to play exaggerated basslines that were still basslines, if you know what I mean, making sure they had repetition. Every once in a while, of course, I loved to play melodic solos. With a jazz band, the sax, trumpet, and keyboard usually play a solo, and maybe the guitar. When it gets to the bass solo, are you really going to be the next dude to just play melodic lines?”

Miller has just released a new album, Laid Black, with an excellent opening track, Trip Trap.

“That was recorded both live and in the studio,” he explains. “It was one of the first tracks we recorded; I had to interrupt the recording of the album to go on tour. We decided to play Trip Trap live, and that answers a lot of questions about the song. Based on how the audiences feel, you realise that some parts of the song are really important, while others are not so important - and also the opposite, things that you thought were really incidental turn out to be the core part of the song.

“And you find out how to approach playing it live. I love the live versions of Trip Trap, but I still liked the studio take as well, so I spent a long time fusing them together. The result is a bit of both and, if you listen to it in your headphones, it gets really ambient and then it gets really tight. I know that’s against the rules, but…” He smiles and shrugs.

Que Sera Sera

The other track we are intrigued by is Que Sera Sera - why choose to do that song?

“I wanted to find a vehicle for [guest vocalist] Selah Sue. I was inspired by Sly & The Family Stone’s version of that song, originally done by Doris Day in the 1960s. Sly took it and flipped it, and that’s where the gospel thing came from. Our version is a version of a version. We took Sly’s version and used it as a starting point, and added another section for the guitar solo and stuff like that. Not everybody may like it; well, tough, it’s too late, I’ve done it!”

We laugh. We ask Miller if, after such a long, illustrious career, the music is still bubbling up inside him, so to speak, or if writing requires effort.

When I was young, the bass guitar was the foundation of every song you heard, in every style, while now, in pop music, I hear no bass guitar

“The music’s always there. It’s simply about deciding what you want to do. On [his previous album] Afrodeezia, we had a lot of history, it was about my roots, and I got the inspiration from the 15th century to today. For the new album I decided that it was now time to take it all up to date. It’s a type of music that everybody in the family can like, like a mixed playlist with contemporary and classic. This album is really the result of that vibe, finding commonalities, finding really new elements that push music forward, but also retaining the things that make classic music classic.”

After looking back, we end on a reflective note. “Bass playing is changing,” muses Miller. “When I was young, the bass guitar was the foundation of every song you heard, in every style, while now, in pop music, I hear no bass guitar. When I was growing up, my responsibility as a bass player was to hold the band together and play the part to keep people dancing. I took it very seriously. Now there’s synth bass, sequenced bass, and younger bass players don’t feel that responsibility. They treat the bass more like a guitar, with chords and a lot of interesting things to do, but they might not be able to groove.

“I’m interested in the instrument’s evolution; if you’ve never had the responsibility of keeping people grooving, you become a different kind of musician. I’ve always liked playing melodically, playing the chords, but I also always thought that you had to have a balance. When it’s time to play bass, you should be able to do it.

“Think about Paul Chambers: he’d hold the band together for a whole song and then, one minute before the song was over, he’d play a great solo, then go back to holding the band together. That takes personality. The guy who supports but also has something to say himself. I would like to be that guy, that kind of bass player.”

Laid Black is out now on Blue Note.