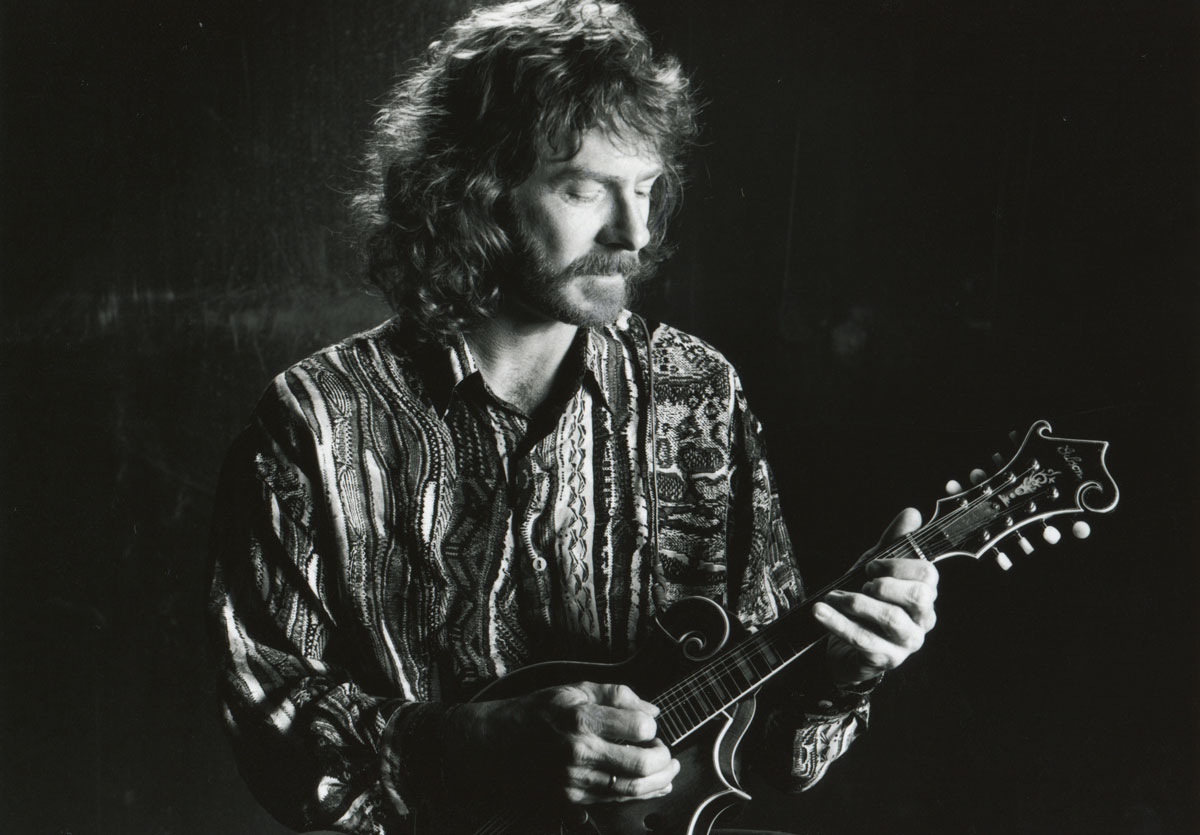

Mandolin master Sam Bush: "The joy is in sitting in a circle and playing. Being an acoustic musician by nature is part of that"

The renowned fiddler and New Grass Revivalist talks recording, technique and the future of music

As a teenager, Sam Bush was a three-time national champion fiddler. In his 20s, he was a founding member of the rule-breaking New Grass Revival, a virtuoso ensemble that revolutionised the bluegrass genre.

Today, he is an award-winning solo artist and bandleader - Grammys, International Bluegrass Music Association, Americana Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement award - recognised as the father of 'newgrass,' and the subject of a documentary, Revival: The Sam Bush Story. The film debuted in 2015, and is now available digitally for rent or purchase.

Written, produced, and directed by Wayne Franklin and Kris Wheeler, Revival, which has garnered its fair share of well-deserved accolades and awards, chronicles Sam Bush’s life, and that of his bandmates, as they worked their way up against an initially reluctant industry that had no idea what to make of a band that turned up the volume while bucking tradition.

Filled with interviews with the musicians and their colleagues, as well as footage from past and recent performances, the story is powerful, inspiring, and serves as both a tribute to Bush and NGR and a lesson in the agony and ecstasy of navigating the music industry - worthwhile viewing for musicians and music fans, including those outside of the bluegrass genre.

During a break between tour dates, Sam Bush spoke to MusicRadar about seeing his life onscreen and what he has learned and continues to learn over the span of a remarkable and influential career.

Let’s start with two comments you make in the documentary. The first is, “Too old to be young, too young to be an old legend.”

It’s hard to believe that I started doing this for a living when I was 18. Now here I am at 66, and I don’t feel that I’m near old enough to be in the legendary status

"It’s hard to believe that I started doing this for a living when I was 18. Now here I am at 66, and I don’t feel that I’m near old enough to be in the legendary status. I just want to keep playing.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"So it is surprising that I’ve been playing music this long, because it’s flown by. I still have that sense of adventure and searching for new things to learn - and there’s plenty out there, believe me. There’s still a sense of wonder about hearing other people’s music, and there’s still a sense of adventure about trying to learn new music."

The second is, “I had forgotten how much I loved music.” On the surface, and certainly to anyone who is early in their career, that sounds like a combination of blasphemy and the impossible. To someone who’s been in this industry for a while in any capacity, it’s an inconvenient truth that we don’t always care to admit. When did you forget, what reminded you, and has it happened since?

"It was one of those things I didn’t know I’d forgotten until I realised I did. That statement can be a little misleading, in that in the 18 years I spent in New Grass Revival, I never stopped loving music, but I became so consumed with the business of music, as the bandleader and in what we went through in, say, the last five years we were together - getting a major-label recording deal and going through that process, getting so busy being the band spokesman and doing the business with our manager and agents - that I found myself not listening to music for fun and not enjoying music as much.

"When the band broke up, which was a tough situation to go through, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I didn’t have a plan. My only plan was that I’d like to stop travelling, because that’s all I had ever done for a living since I got out of high school.

"Then I got a call from Emmylou Harris, who was looking to put together a band of acoustic-style music, and I was in on that. Once I got to playing in her band, the Nash Ramblers, I had no business worries because I was working for her.

"That first year, I realised, 'Gosh, my responsibility is just to show up and play and sing in tune,' and all of a sudden I was listening to music nonstop again, I was a fan of music, I was learning new things. The way she ran the show, I realised that in the Revival we loved to hit everything hard, fast, and furious all the time, and playing with Emmy I learned to let the audience relax and let the band take a breath too. I got to enjoy music again, and it’s been that way ever since."

At one point in Revival, Jeff Austin says of you, “He’s the perfect combination of technical skill and guts.” Your career has been based on taking chances and going against the grain of what’s popular and what works, yet you made it work.

"When we started New Grass Revival, we were a band of brothers and we felt like we couldn’t fail, that we had each other and everything was going to be okay. I come from the world of people that play it like we feel it, and that’s really the story of most of the bands I’ve been in."

Your most recent album, Storyman [2016], was in the works during the making of the documentary. Could you tell us about the instruments you used on that album and some of your preferred recording techniques?

"For mandolins, my favourite mic is a Neumann KM 84. On this particular project I used a Miktek on my mandolin, which is a 1937 Gibson F5 named Hoss.

"The main thing I like to do when we record, and the way we did this one, is I need to sing at the time we record it, just to get a feel for the songs. I need to be singing and playing, which usually means that when I work, every once in a while I luck into a vocal take that I like, but usually I go back and work pretty hard on it.

"Stephen Mougin, our guitarist, is a wonderful vocal coach, and he coaches me on little things such as, 'Lower your chin on this word,' 'Breathe here, not here,' and 'Saying this word differently will help you achieve the note.' So generally I go back and work hard on my vocals, which in turn probably means I have to replace the mandolin track that I cut, too.

"The guitar, again we used Mikteks, and it was my 1991 Gibson Advanced Jumbo flattop. When we’re really on a roll, Dave Sinko, my engineer, and I set up where I can go back and forth between instruments. We have a fiddle mic set up and ready to go, that’s usually a Neumann overhead, and I’ll go direct with the fiddle as well. I don’t usually go direct with the mandolin; acoustic is just fine for the Gibson F5."

When did you start using Mikteks?

"I made their acquaintance, tried their mics, and liked the sound. The next time I record I might try a combination, because I like stereo mics on mandolin, although with digital recording it’s not as crucial as it used to be.

"At one point I stereo-miked the mandolin with a Miktek and a KM 184. I’ve tried different mics on it over the years, and I’m not married to any one thing other than a KM 84 seems to be the most well-rounded for that mandolin. David Grisman was the first one who told me about those mics for mandolins long ago in the 1970s."

What are the differences and similarities in your approach for each instrument?

"I started on mandolin around age 11, fiddle at age 13, and guitar has always been in there. I would sneak and play my sister’s guitar when she told me not to, and so I learned to un-tune the B string just like she left it and not get caught!

It did take me a long time to realise that I was playing fiddle like a mandolin player

"When recording with each of them, it’s funny, some people say, 'Just think of mandolin as the bottom four strings of a guitar backward,' but I don’t think of it that way. I differentiate between all the instruments, but it did take me a long time to realise that I was playing fiddle like a mandolin player. In other words, I wasn’t using the bow for the longer notes to its advantage, or using the advantage of no frets and being able to slide the notes like a human voice, so in that way totally going through different things, even though they’re tuned the same.

"I find my practice routine, especially on mandolin and guitar, is pretty much during baseball season, watching games and playing while I watch! Fiddle - you have to concentrate and not do anything else. There is no one regimen.

"I’m not that disciplined and I never have been. I practise singing probably more than playing nowadays, but I guess the instrument I still find myself practising the most is mandolin. As my hands age and I need to change the way I do things, it’s an exploration of finding out what the hands will do, and do I need to maybe play in a different position on the neck than I used to.

"Crosspicking on the mandolin, which was started by Jessie McReynolds, well, I simply can’t crosspick near as fast as I used to, so the method I used to crosspick, now I don’t do that; I figure out different ways. So yes, I’m always working on my technique, and the technique I’m working on nowadays is going through as the hands slow down as one ages."

Something else you talk about in the documentary is wanting to incorporate rhythm into playing mandolin, and you mention Bill Monroe and Bob Marley as influences on your sense of rhythm.

"I think part of this attitude of rhythm being so important comes from the world of bluegrass music, where even as you solo on your instrument, you’re responsible for the timing, so it’s not like some other forms of music where the drums might be carrying it and you’re a freeform soloist. Within that bluegrass format, you can hear the fiddler even spell out the timing in their solos, as well as certainly the banjo with the flatpick.

"In that way, I became interested in rhythm, and there was something about the mandolin rhythm of Bill Monroe and John Duffey and Bobby Osborne that I just loved - that rhythm chop, that backbeat. Maybe it comes from playing the snare drum and the bass drum in the marching band, and I had to learn just enough rudiments to realise the breakdown in rhythm.

When you’re playing your solo, it’s my job for you to play better, and in my own band, my hope is that when we play together, you play better

"When I was a senior in high school, I took violin lessons for a year, after being a fiddle champion, just to learn more. My teacher was a professor at Western Kentucky University, and she gave me her freshman twelve-page rhythm course. That was maybe more valuable than even the violin lessons, just her helping me break down rhythm and understand 3/4 against 4/4 and how that works, and the syncopation, until it becomes second-nature to you. So through my violin lessons I fell in love with rhythm.

"As a singer, of course, it’s much more fun to play rhythm on the mandolin than to try to hold the fiddle while you sing, and so becoming a singer in the band, more and more I realised that singing and rhythm went together. But I always feel, in any ensemble, when you’re playing your solo, it’s my job for you to play better, and in my own band, if I’m doing my job right and playing in time, my hope is that when we play together, you play better."

One of the things that’s key to bluegrass, and it’s so obvious in Revival, is the camaraderie and interaction between musicians. With technology making it possible to work alone from home, does music risk becoming an isolated activity? What is your message to musicians who are chained to their screens?

"That the joy is in sitting in a circle and playing. I think being an acoustic musician by nature is part of that. We grew up in jam sessions. My dad was the host of fiddle jams in our house, and so growing up with that circle of musicians, my sisters singing, that jam session mentality, maybe that’s the difference in how we keep the feeling of it.

"As young musicians play together, I think it’s pretty obvious which ones enjoy the collaboration, and I think that’s going to lead to a happy musical life. There will always be people who enjoy doing everything themselves; I do that occasionally and it’s fun. But the main joy in life, for me, is playing with others. The joy of the camaraderie and doing it together, I think, will win out over the isolation of technology."