Classic interview - Leftfield: “Leftism wasn’t so much a monkey as a troupe of very large monkeys on our back”

“I think the ‘90s have been dogged by a retro attitude of looking back at the ‘60s and ‘70s and it’s dance music that has kept things moving forward”

Back in 1999, when Leftfield were releasing their second album in the shape of Rhythm and Stealth, Barry Glendenning spoke to Paul Daley - one half of the acclaimed British electronic music duo - about media critics, John Lydon, banned videos and that Guinness ad…

Quite strange, that the first taste of a new, high-profile, electronic album comes through an ad for Irish stout. But then, the current Guinness ad is a classic.

In Jonathan Glazer's stunning, monochrome porter promo, pounding beats accompany crashing waves, as surfers are chased by white horses that materialise from the sea, while a grizzled auld lad solemnly reads a passage from Herman Melville's Moby Dick.

The captivating track in question is Leftfield's Phat Planet, one of several choice cuts on Rhythm And Stealth, the long awaited follow-up to Paul Daley and Neil Barnes' 1995 debut, Leftism.

"No sound system is safe!" declared the cover of one mag when Leftism was unleashed on an unsuspecting public four years ago. It was an accurate prophecy: during a gig at London's Brixton Academy, sound levels reached the highest ever recorded at the venue, while the bass vibrations caused the ceiling to disintegrate.

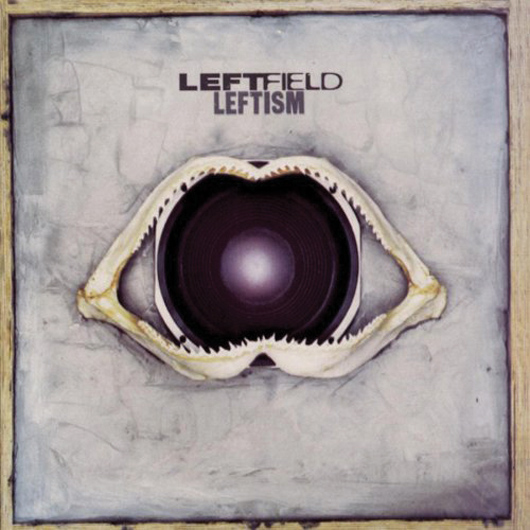

More recently, Leftism has been declared the Greatest Dance Album Of All Time in a poll of top DJs. Warranted praise indeed, for its timeless mix of ribcage-shaking dub and grandiose, futuristic techno sounds like it was made an hour ago.

It redrew the borders of dance music, pioneered a radical hybrid of dub, house and breaks, and threw together guest vocalists from other musical worlds (gothic torch singer Toni Halliday, reggae toaster Earl Sixteen and ageing punk John Lydon, among others) over rhythms redolent of dub, reggae and African music.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Planning and creating

Now, with Barnes and Daley having spent three years in the studio struggling to draw up the architectural plans for new cathedrals of sound, the result is a sequel that is as vital, relevant and challenging as its predecessor. Standout tracks include rising London rapper Roots Manuva freestyling over the sci-fl hip-hop of Dusted, the aforementioned Phat Planet, and Africa Shox, dark and bassy, with a vocal from electro godfather Afrika Bambaataa, far removed from the horrendous torrents of sonic effluvium he's been unleashing on an unsuspecting public recently.

Where Leftism was expansive and grandiose, Rhythm And Stealth is tailored, minimal and ruthlessly effective.

In the conference room of Sony's London offices, Paul Daley is fielding the questions from yours truly, and can't resist a smirk when I ask him if he's read the two-page critique of his latest opus in Q magazine, in which the reviewer handed down a mediocre three out of five to Rhythm And Stealth, concluding that "Leftfield have become victims of their own propaganda. By allowing themselves to be billed as the music of the future, they have nowhere to go now they sound too familiar.The future they once promised is now. And there's just no getting away from it, it just doesn't sound like Leftfield." Ouch!

"No, I haven't read that Q review yet, but I"II read it in about a month. I've heard it's awful," Daley smiles.

When I tell him that it’s not awful, but hardly glowing either, he laughs dryly. ''I've a great story about that, actually. A friend of mine knows the journalist who wrote it, and the day after my friend read that review he said he saw the same bloke walking down Oxford Street wearing a Leftfield t-shirt! So, y'know, he can't dislike us too much. Then again, maybe all his other shirts were in the wash that day."

But doesn't all this negative press get Daley all riled? "Nah, I'm trying to be positive about everything at the moment," he explains, trying to be positive about everything at the moment. "But, y'know, he's entitled to his opinion. A lot of people caned the last album... but that's their prerogative. I can't make people like our music.

A lot of people caned the last album... but that's their prerogative. I can't make people like our music.

"Some people slag you off to be anti-fashion, some people slag you off to be fashionable, y'know. Some people will say you're the greatest thing since sliced bread, just to be fashionable, or because they want you to like them, If they start saying, 'Paul Daley is a wanker 'cos he's got smelly feet,' then that's different because that's personal. How do they know if I've got smelly feet? They don’t know if I'm a wanker because they don't know me. You can’t judge someone’s personality by their music.”

It seems Daley and Barnes (who is away on holiday at the moment) are at a loss to know what kind of reception will greet the release of Rhythm and Stealth. "We've no idea, mate," comes the honest response. "The reaction to the first album was mixed. We got some good reviews and in some quarters we got a slagging. I think if you think that everyone's going to say you're great, then you're very much mistaken. But then, to assume everyone is going to think you're shit is being a bit too much of a pessimist. So it's nice to get a kind of a balance. It's healthy to get a bit of criticism. It makes you feel human."

As a thirty-something with increasing amounts of face and considerably less hair to wash on a daily basis, Daley is prepared to concede that the ageing process has forced him to curtail some of the more, er, sociable aspects of his trade.

“It takes me a week to get over things now," he agrees. "I’m not able for it any more.”

What kind of things? "Y’know just things in general," he laughs obliquely. "I can’t do as much as I used to. Naturally, as you get older your body can’t take it y'know what I mean? Having said that, I heard a good story about Joe Strummer from The Clash once. A couple of years ago, a mate of mine took him to a rave where he took his first E. Beforehand, he wasn't very sure whether or not he liked the music and then afterwards he thought it was the best experience of his life.

"I've done it to John Lydon, actually [whom Leftfield collaborated with on 1995's awesome Open Up], and watched him turn from an arch cynic into this loved-up bunny rabbit. He thought it was great!

“John is actually a big music fan, which is something I don’t think a lot of people appreciate. He’s genuinely interested in dance music, although he probably wouldn’t admit it himself. He has this punk image to maintain, so he just slags it off al the time. He’s pathetic [laughs].”

So how did our intrepid explorers of electronica feel when Leftism was bestowed with the accolade of Greatest Dance Album Of All Time? "Yeah, that award was given to us by The Angling Times," he laughs. "No, it was wicked. Y'know, at the end of the day DJs tend to be quite an honest bunch - they tend to like something or they don't - so you know they're not saying it to be fashionable. It's quite nice."

And how about the fact that Leftism came second in our reader votes for Top 25 Electronic Records... Ever in FM77 (number one was Oxygene, just for the record)? "Oh, we were definitely surprised and very flattered.”

But surely such gushing praise intensified the pressure on Leftfield to deliver the goods again this lime round? "Definitely," agrees Daley. "But luckily, that only happened a few months ago, so for us, it was a case of going, 'Shit, I hope they like this one'.”

And what happens if they don't? "Well, that's tough titty, isn't it? It's a wicked accolade to have but you can't get too wrapped up in that kind of shit."

When I ask Daley to name his favourite dance album of all time, he leaves me flabbergasted. I'm sorry, but I could have sworn you just said Boney M.

"Yeah," he grins. "Boney M's Odyssey. I listened to it again the other day. I just realised how good they were. I know how cheesy it sounds but it's the production on it.

"It's a wicked album and they do a great version of that Neil Young track, Heart Of Gold, believe or not. But of recent limes, there's a lot of great dance albums around, y'know. I don't tend to listen to albums any more. Any I would listen to now, it’d be old ones. Listening to albums was very much a thing of the ‘70s and early ‘80s for me, as a kid.”

As the world of dance music exploded overground in the mid-’90s, many of its luminaries wore a clearly identifiable Leftfield influence on their sleeves (or grooves), among them Underworld, The Chemical Brothers, Basement Jaxx, Daft Punk and Orbital. You'd assume this would be a source of great pride for Daley.

"I finally do admit that we have influenced music in the 1990s," he muses. "I wouldn't have said it before but I stand up and say it now; not only dance music but rock music, too. It's cool to make music, have a few hits, then be forgotten, but to influence things and take music off in another direction... that's something to be proud of. It's not like we set out to do it, but it happened by accident, which is even better."

Rhythm and squabbles

During the making of Rhythm And Stealth, rumours abounded of serious studio rifts between Daley and Barnes, apparently stemming from a mutual dread that, with Leftism, their finest hour had passed. An honest bloke, Daley makes no attempt to deny them.

"Sometimes it was good, sometimes it was bad, but it was like that for the first album as well. It's been like that for ten years. Of course we argue, because our relationship is like a marriage. You're in a small room with a couple of other people. You have an engineer and you fall out with him, you fall out with the tea-boy; I even fell out with the studio manager!

Can these techno trials and tribulations be attributed to the fact that the success of Leftism was a monkey on Leftfield’s back?

“It was more of a baboon,” Daley laughs. “It wasn’t so much a monkey as a troupe of very large monkeys. Essentially, though, we wanted to prove that we had something to say sonically, in a musical world of quite a lot of, er, shite… with some good bits here and there. Me and Neil have got our standards, and our standards are quite high.”

A bit too high, perhaps? “Well, no, when you consider the alternative, which is sitting in the studio going ‘Well, that’s alright, that’ll do’. We’re just not like that. We did put the pressure on ourselves. I love it when people have commented or written about this album and mentioned sounds or noises they’ve never heard before; that makes it rewarding. I don’t want people to go ‘Oh well, it sounds like Leftfield’. I want people to listen to it and go ‘Oh, what’s this?’

“I think the ‘90s have been dogged by a retro attitude of looking back at the ‘60s and ‘70s and it’s dance music that has kept things moving forward.”

''Me and Neil have a working relationship and we've never really stopped and analysed it. At the end of the day, when you work that intensely, it goes beyond friendship. Spending that much time together probably isn't good. I mean, I can be a total prat with studio people, but that's my personality.

"We're there to do something creative and if it means arguing about it, then that's the way it is. That's part of it. It's not personal, it's more when we have bottlenecks and we're discussing where to go from here… that's when things can get a bit tense.''

Is there any truth to the rumour that, at one stage, the album was nearly scrapped? "Yeah, Daley nods. "There were times when we were making this album that I went home from the studio at night and thought, 'We can't make another album. It ain't gonna work'. I was thinking, 'Well, all that music that we put out between 1989 and 1996, that was Leftfield, that was our time.'

"There were times when I thought like that. There's this self-doubt in what you're doing and because we were pushing so hard in trying to make it sound different from the last album without disappearing up our own arses, it put the pressure on us. We were wondering whether or not it was valid."

And now? "Well, now when I listen to it I think it is valid. When I listen to everything else being released, I think that ours is very valid. It's dance music."

So Leftfield don't actually go into the recording studio with the specific intention of redefining musical boundaries? “No, but with this album we did go in with the attitude of saying, 'Let's make an album which doesn't sound like a bunch of TV commercials', which is kind of ironic when you consider that one of the tracks is already being used on that Guinness ad. The album hadn't even been released and it was already on a TV ad! But it was such a good advert that we had to let them use it. It could have been anything really.

“In a way, the fact that it's a Guinness ad seems to have bypassed a lot of people completely. The first thing people notice is the visual thing, the second is the music and the third is the actual product that’s being sold. In a way, I feel a bit sorry for Guinness because they’ve been overshadowed by the music and the film.”

Known and unknown

Before meeting him, I wouldn't have been able to pick Leftfield's Paul Daley out of a police line-up. Indeed, like a lot of faceless boffins, he seems most comfortable being heard and not seen. A fair comment?

"Perhaps when I was younger I was interested in fame, but I'm 36 now and you change as you get older," he expounds. "I’m just interested in music.

"When I DJ, I get people asking me why I don't play any Leftfield records. I just explain that I'll happily listen to other people play Leftfield records, or I'll play them at home. I DJ to salute other people's music, not to promote myself. l think the whole hype and celebrity thing sometimes overshadows the music."

Two words spring to mind: 'Fatboy' and 'Slim'. "Maybe," responds Daley after a lengthy pause. "At the end of the day, Norman Cook's been making music for a long, long time and nobody knew what he looked like for years. So he's probably decided it's time people know what he looks like so that he can get a bit of appreciation for what he's done.

"We're doing press on this album that, four or five years ago, I wouldn't have done. I wasn't being precious but I would have been of the opinion that people should just be into the purity of the music.

"I think now I've probably mellowed a bit and I find it a lot easier to talk to people such as yourself. I can deal with the fact that people want to talk to me like you are now, or I can deal with the fact that people want to take my photograph, whereas four or five years ago I didn't want to deal with it.

"We started Leftfield to get away from all that star thing," he continues. "It was the facelessness of the scene that really appealed to us because we could just concentrate on the music. We could make records in our bedrooms and then in two or three weeks those records were being played in the clubs. And we could go along to the clubs and stand there listening to those records and nobody would know who we were."

Wheels and deals

A few years ago, Daley was surprised to find himself spinning the steel wheels before 20,000 people at Tribal Gathering, a state of affairs he could never have foreseen a mere five years ago.

“I never saw the whole scene ever being like it is now," he explains. "When we were making Leftism, I thought the whole scene was on its knees taking its dying breath, because a lot of people were trying to foresee the end of vinyl. The DJ culture is what has kept vinyl going. IU was in America a few weeks ago and l could see that a lot of people were getting into it over there. They're a bit behind the mark, like with punk but, y'know, better late than never. Apparently you have these big raves going off in Oklahoma now, in the middle of nowhere. You wouldn't have had that a few years ago.”

Rather more pathetic was the recent decision to ban the video for Leftfield's Africa Shox, which features an alienated derelict wandering the streets of!\ewYork, his limbs shattering like porcelain every time someone bangs into him. Directed by pop promo genius Chris Cunningham (who was responsible for Aphex Twin's infamous clips for Windowlicker and Come To Daddy), the video is both powerful and funny. Daley is understandably annoyed by what he sees as a typically hypocritical act of censorship.

“There were lots of reasons why they banned it," he sighs in resignation. "One of the main ones was because there's been a lot of violence in America with all these shootings, and they just get really, really uptight about any kind of negative violent images. I find it very hypocritical... actually, I'll give you an example. You've got this really cheesy Euro house record called 9pm Til I Come, and you've got eight-year-olds dancing to this going, 'Yeah, 9pm 'til I come!' That's like selling porn to children. And then there's that record about having sex on the beach, and you've got little toddlers running around singing it. I find that very offensive.

"That video we made was like a dark comedy. It's not meant to be taken seriously. They sent us a list of reasons why they banned it: drug abuse, fear, loss of limbs, death, promotion of drugs, y'know.”

Were you surprised when it was banned? "No, we were expecting it, to be honest. The first time I saw it I thought, ‘a lot of people aren't going to like this’."

No doubt it cost an arm and a leg. “Well, it's ironic you should say that, because that was one of the things they didn't like about it, the fact that the bloke in the video lost his arms and legs! But, you know, the fact they've banned it just makes people want to see it more. So they're doing us a favour really. But I do find that kind of thing very hypocritical. If you wanna really look into things, there are a lot of videos on during the day, or on Top Of The Pops, that I wouldn’t want my kids to see. It's just hypocritical."

From ‘over-exposure’ with Guinness and under-exposure with banned videos, Leftfield are getting the best of both ends of the publicity spectrum.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.