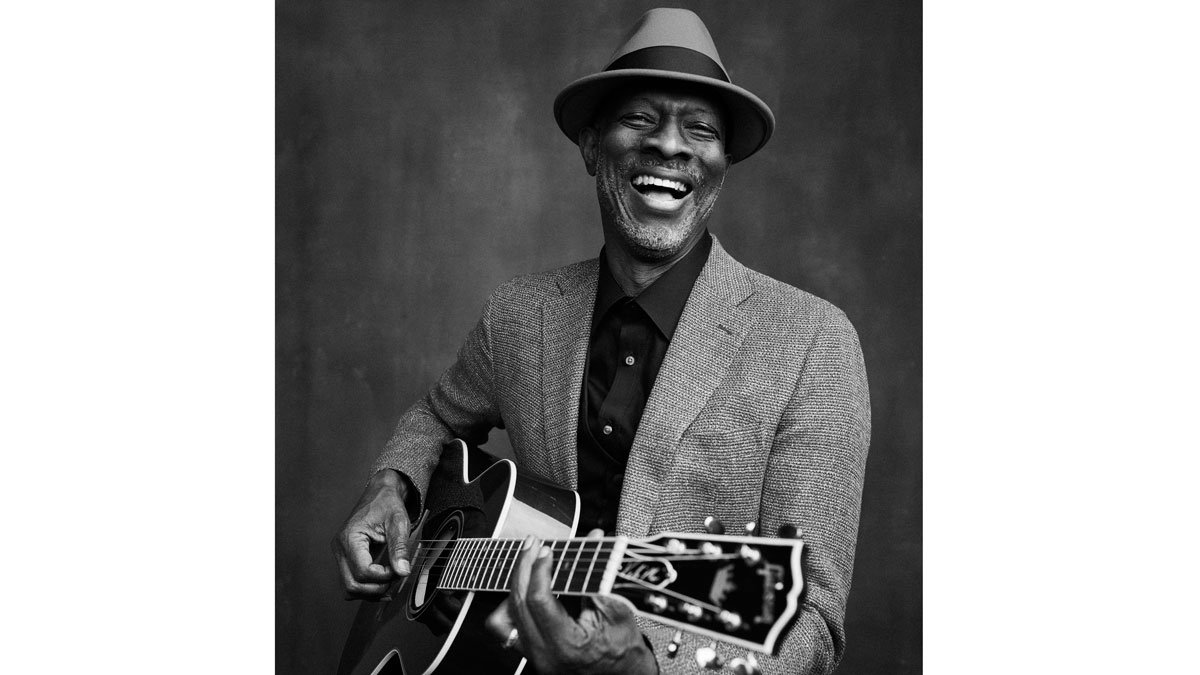

Keb' Mo': "The melody is king and the rhythm is king"

The Grammy-winning bluesman talks American history, the power of great collaborations, and explains why his songwriting goes all the way back to Bach

Keb’ Mo’ is onstage, soundchecking with his National Reso Rocket steel guitar, bathed in the afternoon sunlight that’s pouring in through the windows of London’s Union Chapel.

If there is something a little on-the-nose about this messianic visual, the bluesman is nonetheless in the Chapel to deliver some spiritual uplift by way of a blues sound that takes on all kinds of influences and reimagines them anew.

American folk, bluegrass, Afro-Cuban jazz, maybe a little country honky-tonk, too... It’s all in the stew there somewhere, and that is what makes Keb’ Mo’ - born Kevin Moore - so interesting.

In some respects, his latest album, Oklahoma, is an angry record. Or at least it could have been. As he explains, it is animated by America’s troubled racial history, its present political strife.

But also, equally, it is a hopeful record that reaffirms America’s promise. As the song goes, Oklahoma is going to be okay. So, too, America. And there’s no shortage of positivity on an album that sees Keb’ Mo’ invite the likes of Robert Randolph, Roseanne Cash, Taj Mahal and Andy Leftwich into the studio. A duet with his wife, Robbie Brooks Moore, on Beautiful Music, closes the record with a little marital bonhomie.

Here, he walks us through his songwriting process. In the early years, when he was a primarily a back-up player, Keb’ Mo’ was on the staff of A&M Records, an experience that sharpened his sense for arrangement.

As a guitar player, Keb’ Mo’ is not a showy player. Maybe that speaks to one of the first rules of blues guitar: don’t overplay. But listening to him talk about writing the Oklahoma, the song and the record, it’s more than that.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Maybe it’s because he has learned to leave plenty of space in the mix for the band, his collaborators, and especially to leave room for the melody, the vocal and the rhythm. Because as he will explain, within any songwriting structure, these are sacrosanct.

We should start with the record. You are singing about Oklahoma but really it sounds like you are really singing about America.

“Oklahoma is a little microcosm of America. ‘Cos what you’ve got there, you go through the lyrics, you got ‘I can feel the spirit/liftin’ me up/takin’ me higher. I can never get enough of Oklahoma.’ That’s pride, y’know what I mean.

“Cowboys and Choctaws - Cowboys and Indians. That’s the history. Oklahoma, Chickasaws and outlaws. ‘Jesus on the mainline,’ that’s the religion; not like the pure religion but that kind of religion of convenience. Like, ‘Praise the Lord. Pass the ammunition.’ [Laughs]”

It seems like Oklahoma has forever been the centre of hardscrabble America, of labour struggles, the dustbowl. You can see those struggles in various guises across America. Is that what you wanted to get at?

“Yeah, it is. The dustbowl Oklahoma. Oklahoma is like the home of tornadoes... It’s kind of an evil place. It’s like Texas but a little more evil. Because you know what the bridge [in the song] is about? You know the story of Greenwood, Archer and Pine? Well that was the location of ‘Black Wall Street’ in the ‘20s.

“There was a neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and it was at the intersection of Greenwood, Archer, and Pine, and it was an affluent black neighbourhood. This was just 60 years after slavery. So now you’ve got mansions, great businesses thriving in Oklahoma. This is a piece of history that was kept a secret. It’s in no books. Nothing. It’s the biggest racial holocaust in America that every happened and they don’t even talk about it.

America’s history is dark. It’s very dark

“There was an accusation of a white woman being sexually accosted by a black man who lived over there in that area and the hate just blew up. It’s 1921, the racial tension is thick, the white people literally went over there and burned the whole thing and bombed it, killed a bunch of people. It was gone. [The bridge] is inviting people; if you’re curious, maybe you can Google Greenwood, Archer and Pine.”

Placing this story in a song is very much an act of storytelling.

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m not a poet; I’m a storyteller. America’s history is dark. It’s very dark.”

How important was it to get Roseanne Cash on Put A Woman In Charge?

“I called a friend of mine, Ed Zimmerman, who is a music aficionado and an attorney in New York. And I didn’t know who to get. I wanted to get somebody who was kind of loud. A big star always works, but big stars don’t answer my phone calls. I’m not really in that league - and, plus, you’ve got to talk to their managers and everybody.

“We just called Roseanne, she heard the song and was like, ‘Yeah, I’m in.’ She was the perfect person. She’s got the power, the swagger. She puts her money where her mouth is. She’s a badass. She was the perfect person to do it, and I would never have thought of. It’s exactly what the track needed.”

Speaking of collaborations, you’ve got Robert Randolph on this, too. Did he come in at the start?

“I produced G Love’s new record. I was working on that and he was a guest on that G Love record. So I said, ‘Hey, why don’t you put something on this record?’ He was right there. We are buds and everything, but I didn’t have anything for him to put on there. I had this scratch version with the tempo and the song.

When I write a song, I make the form and then I’ll do it to a click-track, and it’ll be this crappy track. I don’t do demos!

“That’s what I do, when I write a song; I make the form and then I’ll do it to a click-track, and it’ll be this crappy track. I don’t do demos. [Laughs] The record is never as good as the demo, so I did that and said, ‘Would you just play and vamp on this?’ And he played on that.

“The vamp that you hear on Oklahoma, that was the first thing put on [the record]. We put the scratch track down and - holy shit! - it was good. What happened was the song Oklahoma, became like a three-minute intro to his lap-steel solo! [Laughs]

“He was just sitting on the couch in the studio. He had the steel on his lap, and we were just playing. The song Oklahoma, and the fact that it is the title cut, is either the smartest or the most stupid thing I’ve ever done, calling it Oklahoma and not something else.”

How so?

You want to leave room for the listener to have their own experience

“I was playing the rhythm. Do-nun-do-nun-nun. I was over my sister’s place playing it, and I thought, ‘Well I guess I got to think about a hook for this.’ ‘Ok-la-ho-ma!’ What the fuck am I gonna do with this? I’ve been in Nashville too long.

“So then it was towards the end of the year. We were having our New Year’s party at our house. We invite everyone over. Anyone can come over to the house and we cook food and jam. So I am introduced to Dara Tucker. She’s at the party. We set a writing session for the next day, and then she comes over and says, ‘What you got?’ I said, ‘Nothing.’ I said, ‘Where you from?’ And she said, ‘Oklahoma.’ [Pauses] Okay, now it’s getting crazy. I’ve had a few experiences in Oklahoma; she had actually lived there. She did me like an ‘O-K-L-A-H-O-M-A’ football game chant. [Claps] ‘Everything is going my way!’ Cheerleading. So we put that in there. We wrote the song.

“We looked up Greenwood, Archer and Pine, talked about all these things, looked up all the native tribes that lived in Oklahoma. Came up with the whole ‘Cowboys and Choctaws/Chickasaws and outlaws.’ Got all that together, and then Greenwood, Archer and Pine was the bridge. This is the peak of it. Then we go up.

“1920. I’m thinking about all these African-American people, and they have survived slavery, and they have this higher consciousness of people who are hopeful. So I go, ‘Over on Greenwood, Archer and Pine lives an elevated state of mind.’ So keep on reaching for the sky. The backstory is that something really bad happened there but we’re gonna keep going. I think it has layers, the bridge.”

That’s the thing with songwriting; you don’t have to be explicit about what you’re singing about.

“You want to leave room for the listener to have their own experience. And that song is about change. We’ve got to go through things differently. The Obamas came in and what they did was they put hope back in. The hope is that we have changed, that we have become bigger.”

What about the gear you used on the record?

“Usually I played that one out there, the Keb’ Mo’ Gibson. That’s my number one guitar. I used that one and a Hersch guitar - I used a Hersch mandolin. I used the National Reso Rocket. Those are basically what I use onstage. The electric solo on Cold Outside is a 335 Gibson going through a Mesa/Boogie [Mark V] 35. And yeah, it turned out to be not that many guitars.”

You have spoken before about how you wish you had taken a music degree. Didn’t you write for A&M? That’s a form of college.

“Yeah, that is a form of college.”

What did you learn about arrangements?

We did Bach chorales. We had to write these four-bar, eight-bar bach chorales with four instruments, y’know!

“They are all based on Bach. It’s the voicing. It’s the simple chords and voicing. I learned it in LA City College from my Music Analysation class. We did Bach chorales. We had to write these four-bar, eight-bar bach chorales with four instruments, y’know!”

Seriously, the foundation of your songwriting is Johann Sebastian Bach? You’re kidding.

“No! [Laughs] No. That’s why it’s like ‘Duh-dum-duh-dum...’ Like these parallel motion things, like Bach has? It’s all chorale, and that is the bedrock of the way classical music is created, with a little parallel motion, a little contrary motion. So the melodies, and the stuff like that, I don’t know if I am achieving it but that is how I think: two notes, one being the vocal, with two notes, it’s the chorale.”

It’s like a conversation.

“Yeah. The vocal. I think the melody is king. The melody is king and the rhythm is king, and everything you put around it is supposed to enhance that. Because the rhythm is primal. That’s what makes you go; that’s what brings you in and keeps you interested. That’s the heartbeat that makes you go. And then the melody is what makes you sing and hum along and memorise the words. Simple melodies. The chords are the emotion; they signal the emotion.”

And if the foundations are solid you can do all sorts of things with your sound. You might be rooted in blues but you’ve got Andy Leftwich from Kentucky Thunder playing on Oklahoma, too, which is folk and yet it fits perfectly.

“I was about to do a guitar solo on there, and I was like, ‘Wait a minute. That would be really stupid.’ You’ve got this Latin thing going. A sort of Afro-Cuban thing. Then you’ve got Robert Randolph at the end with the sacred steel, and going to church at the end.

“So what does Oklahoma have? Lots of bluegrass? [Claps] You’ve got to bring a bluegrass player in! Andy came in. And when I heard the violin solo, I went, ‘That one’s called Oklahoma.’ And that was it.”

How would you describe your sound?

“It’s folk music. Blues is folk music. I’m a folkie! [Laughs]”

Oklahoma is out now via Concord Records.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.