“I am always able to come up with brand-new chords that no one has been stupid enough to sing over”: Page Hamilton on harmonic curiosity and the aggressive expansion of Helmet’s musical vocabulary

Hamilton discusses how drop tunings, NYC, fine art, Led Zep, the Bee Gees, Glenn Branca, jazz and soul all played their part in shaping Helmet's unique, uncompromising sound

Those who might have feared that Page Hamilton has lost any of his songwriting chutzpah and the capacity for subverting his audience’s expectations will be set at ease during the opening seconds of Helmet’s new album, Left.

It opens with Holiday, a track that starts as though it has already begun, already at its half-way point, surfing on big chords and a hazy vocal melody. Like, what have we missed? Well, for starters, we have missed Helmet. This is their first studio album since 2016. But otherwise nothing. We've been ambushed by Hamilton’s choice to present the song as though the first bars were excised by an accidental mouse click. And it pays off.

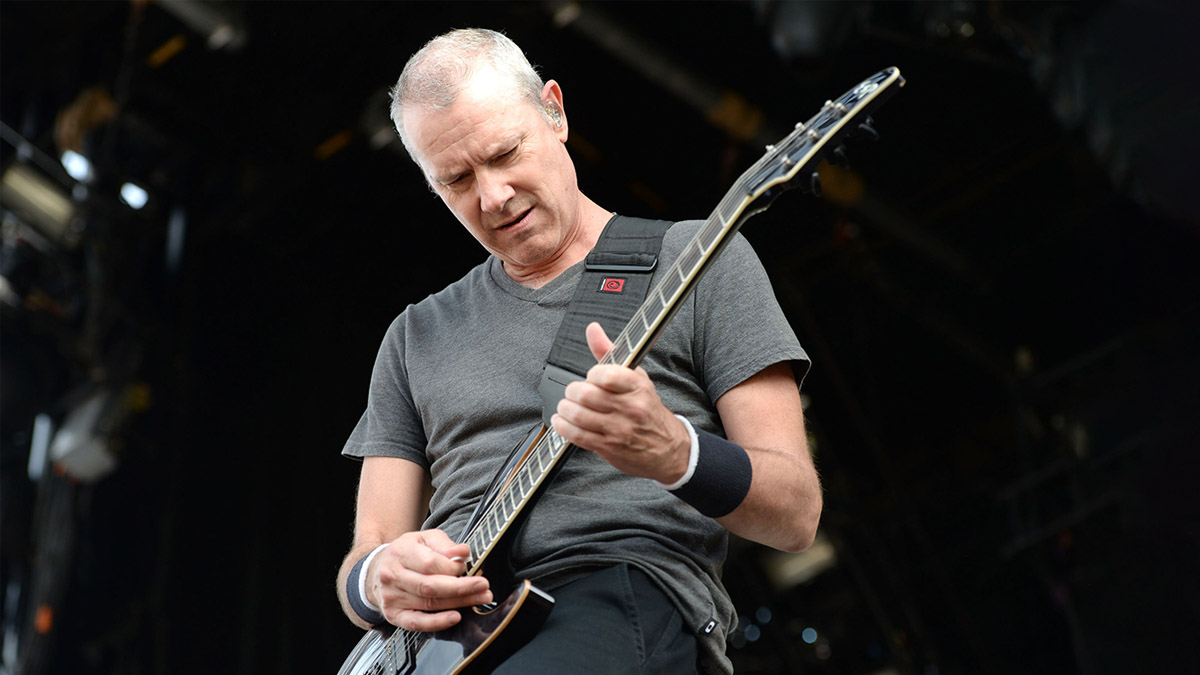

Holiday wrong-foots us, and in a sense this is an intro, a moment of dramatic suspension before the song hurls us into the band’s stock-in-trade of muscular electric guitar, riffs bustling around a jagged, angsty rhythm, the tightly wound drop-tuned riff-o-rama spiked with the avant-garde electricity of Hamilton’s jazz-inspired solos popping off his ESP Horizon.

All of which made Helmet one of the most influential bands of the ‘90s and yet the one that no one could copy.

“It’s funny, a lot of bands that got on our bandwagon or told us they are influenced by us or whatever, they never really explored the harmonic vocabulary,” says Hamilton. “Gavin Rossdale, when I produced his solo record [Wanderlust], he used the chords from I Know but he just straight-up ripped it off, and his demo, his home demo, started with drums just like I Know and I said, ‘Gavin, we are not fucking doing that. That’s I Know, exactly!’ And he’s like, ‘Well I played it for Bono and he loved it!’ ‘Good! I’m happy for you. Go sell another 12 million records and stop ripping me off.’”

Ultimately the collaboration worked. Rossdale was impressed, and not just by the guitar tone, which was why Interscope co-founder Jimmy Iovine put him in touch with Hamilton in the first place. “We really did well together,” said Rossdale, speaking to Spin in 2005. “He’s also a great dresser – a very stylish man.”

Today Hamilton joins us from his home studio space in LA, which by the sounds of it is more home than studio. This is where he ticked off the parts that he didn’t get around to in the studio where he was accompanied by producer Jim Kaufman, whom he first met when Kaufman engineered 2004’s Size Matters, and his vocal coach Mark Renk, whom he credits with extending his voice's range and reducing the need for throat lozenges.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I have a couple of Neve channel strips with compressor, EQ, and mic-pres, and I have a couple of SSLs, which is plenty for one dude,” says Hamilton. “I did a fair amount of backing vocals here and things like Reprise, that song half-way through the album. I did a lot of stuff like the 12-string here. The Coltrane piece I did here.”

Maybe I was afraid of pop music for a minute there because I’m a jazz guy and I thought that if things sounded remotely catchy or familiar then it wasn’t good

The John Coltrane piece is a reworking of Resolution, from 1964’s A Love Supreme, and it closes the album with the fizz of drummer Kyle Stevenson’s cymbals and Hamilton turning Coltrane’s tenor sax into distorted guitar.

After four or five takes at the solo, at times finding himself so far behind the beat he was in a neighbouring zip code, he got it down. A jazz coda seems an appropriate way to close an album that reintroduces the band and reminds us of what made this sound so exhilarating in the first place, with Hamilton caught between his book-schooled knowledge of jazz and the informal melodic schooling he got from FM rock radio, Motown and soul. Not to mention playing with David Bowie.

“Maybe I was afraid of pop music for a minute there because I’m a jazz guy and I thought that if things sounded remotely catchy or familiar then it wasn’t good,” he says. “This was in the early ‘80s. I was writing and then, ‘Nah, that’s a chord that everyone knows. I’m not using that.’

“When I started I wanted to be this anti-songwriter because I got so sick of everybody talking about some new dude doing G, C and D again but not as cool as Bob Dylan or Bob Marley or whatever. It was that whole era of Americana music that just didn’t click with me.”

Nowadays Hamilton can see the appeal in those chords and just might use them. Some of the ideas that informed his songwriting came from the unlikeliest sources. Who would have forecast this architect of audio nerve headaches like Turned Out and Bad Mood would look to the Bee Gees as a sonic reference?

Left is animated by an anxious energy and yet the easy sessions with Kaufman have left Hamilton the air of someone who has just got a load off. But he promises us that the efforts to widen Helmet’s musical vocabulary – the chord voicings, the rhythms, the harmonic transitions – continues unabated.

Here, Hamilton tells us how that process is a constant evolution, why he might mix up the count but never be down with shredders or math-rock's conspicuous consumption of odd meters, and how the influence of Led Zeppelin, Motown and soul sits alongside the pioneering work of Glenn Branca, whom he performed with at the start of his career. All of this stuff – music, art, literature – is connected.

But first we'll talk guitar solos, because no one quite uses them like Hamilton...

Some of your solos sit up front and are in your face, like in Big Shot, but others sit way back in the mix, like on Bombastic. How do you choose which goes where?

“Yeah, there’s some new harmonic territory that I have been exploring on this album. I am always able to come up with brand-new chords that no one has been stupid enough to sing over. Bombastic being one. The chords are totally fucked but they sound amazing in that bridge. It’s like a C9, but then I move the root and the fifth up a half-step, but this Pentatonic scale works against it. [Sings vocal] And point being: solos are part of the orchestration, right?

“To me, I never got... Well, I guess I get it. It’s a macho thing. I dunno, ‘My dick’s bigger than yours’, the shredder thing. ‘I can play so fucking fast!’ That is interesting to me for three minutes and it’s like, well, there’s gonna be some kid whose going to come along and play faster than Steve Vai, if it hasn’t already happened.

Solos are part of the composition, and sometimes it is going to be Rick Nielsen jumping out for eight bars and punching you in the face with the solo or like the Stooges’ Raw Power.

“But, to me, solos are part of the composition, and sometimes it is going to be Rick Nielsen jumping out for eight bars and punching you in the face with the solo or like the Stooges’ Raw Power. When I played with Bowie I talked to him about that. I told him I loved that mix and he had no idea that I knew that that was him.

“That is a musical choice. And we did that with Strap It On. Stooges were a big influence on Strap It On that, where Wharton [Tiers, producer] was like, ‘That solo is loud!’ ‘No, no, no. This one needs to jump out, it needs to jump out at you.’ There are other times, much like these Helmet chords that have a lot of space in them, and I'm pulling the 3rds out a lot of the time.“

Tell us more about these chord voicings. Those are crucial to your songwriting.

“There are no thirds in a lot of the classic Helmet voicings, like I Know or See You Dead. Those voicings have no thirds in them; I might sing the 3rd, or I might overdub an upper-tertial part with the 3rd, where it’s just the top four strings where I change the tone. I am more interested in the song than showing off.

“I can play fast. I can play fast enough. I mean, David Gilmour can play fast enough. He said he tried to play faster and practice more and it is not in his DNA, and thank God because nobody wants to hear somebody shred on Comfortably Numb. You wanna hear this emotional, fucking gorgeous orchestra – literally he is part of the orchestra there with the Michael Kamen strings, and to me that is more interesting.

“That is how I have always approached it. I am not Steve Vai – and I admire him, Joe Satriani, any of these guys, I have great admiration for them, but I feel like compositionally their whole thing is geared towards, ‘Here is the solo.’ The song is secondary.“

You can still light up the fretboard.

“I write lyrics and I sing, and I consider myself a writer – a budding young composer. ‘A budding old composer!’ That’s a thing that Bowie said to me once. He said, ‘A budding young songwriter? Advice for budding young songwriters?’ And he turns and looks at me and he’s like, ‘I nicked half my songs from the Inchworm, Danny Kaye.’

“I listen to a shit-ton of Ralph Vaughan Williams, one of my all-time heroes, and Beethoven, obviously. I teach riff-writing with the 5th Symphony because it is the best heavy metal riff ever, right? [Plays Beethoven on an unplugged semi-hollow] And that is more interesting, to me to have the guitar solo be an integral part of the composition – and it should be exciting! It should take you somewhere!”

I was always on the subway drumming out rhythms. I was always fascinated with three against four and five against four and all those things, drumming them on my legs to pass the time

It takes me to New York, because that approach, in which you make it all busy and discordant and harmonically complex, gives the audience that impression that your transposing the thrum of the city into the song. Did the city have that effect on you?

“Yeah, there’s no question that it did. I was riding the subway around. I used to live in Harlem, in Dominican Harlem, and then moved to the East Village in 1989 or something like that, and so I spent a lot of time on the subway.

“I bartended in the East Village and I would have to go all the way to Harlem, from east side to west side, downtown to uptown. Where the fuck was I? 131st or something, I can’t remember now but I was always on the subway drumming out rhythms. I was always fascinated with three against four and five against four and all those things, drumming them on my legs to pass the time.”

And there’s a natural rhythm there too.

“When you are on the subway and close your eyes there are so many sounds. I used that Steely Dan line from the album with Kid Charlemagne, The Royal Scam. ‘The mechanised hum of another world…’ It’s from the song Don’t Take Me Alive. ‘The mechanised hum of another world,’ I just fucking love that line. That’s New York, and it seeps into your soul because it’s musical.”

“Music is everything, everywhere, and that’s what New York is. I wouldn’t have become the writer I am without having spent 20 years in the city. I mean, I grew up in Oregon and it was pine trees and flowing rivers, which are beautiful but…

“My drummer, [John] Stanier, when we rented a place up in Woodstock to get out of the city and write Aftertaste – because the band had become this thing and I felt kind of smothered. He was like, ‘Oh great, you’re gonna be sitting naked in the woods talking to squirrels and writing acoustic.’ [Laughs] ‘Well, we’ll see!’”

Tell us about Glenn Branca's influence on you.

“Glenn [Branca] is probably the most underrated, unknown, and most influential composer of the last hundred years. People will say, ‘Where did you come up with this stuff?’ Man, Glenn wrote numbers on stuff. It wasn’t standard notation. It was a series of numbers: 1, 2, 1, 2, accents over the 1, and then there will be a staircase, and that meant play a triad shape, but then it was all tuned unison, to Es or Bs.

“And he had soprano, alto, tenor bass, and then the harmonic guitar that he invented. And it was about these rhythms. The drummer was always in four, and we were playing seven, and I came up with lessons for my students based on that.

Glenn Branca is probably the most underrated, unknown, and most influential composer of the last hundred years

“It just occurred to me. During the pandemic I had been teaching, and though, ‘God, my rhythms are so boring. I’m writing these boring rock songs.’ Well, set a metronome up, mute your strings, don’t worry about your left hand and play this. ‘You can count to two, right? Three? Okay, so 1, 2, 1, 2, 3 / 1, 2, 1, 2, 3...’ You are playing five against four. It simplifies the whole process. Glenn was genius enough to figure that out, and then he started notating stuff, and that is more complex because most guitarists don’t read music.”

That can make it difficult to learn and to teach.

“Thinking of ways to get that musical vocabulary, that rhythmic stuff and from a harmonic standpoint in there, I have this process. I tell my students they have to know how a chord is built, and then when they know what notes go into a Cmaj#11 you can find it anywhere on the fretboard.

“You have to learn your fretboard obviously but I can play that chord all over the place because I know I just need the root – I probably don’t even need the root – the root, the third and the #11 and there you go. Find those four notes in any combination. And that’s how I developed the Helmet vocabulary.

“I got that riff in my head for Repetition, and the note was an octave below that note I was hearing and then I thought how could I do that? And if I just tuned that low string down a whole step I could play it with one finger, and then all of a sudden I started fumbling around with chords and hearing things.”

Your rhythms don’t always call attention to themselves – it is something the audience feels rather than thinks about. Like when you watch Halloween and John Carpenter’s score has that count but you’re not conscious of it, not like some math-rock.

“Yeah, that’s like shredder’s solos for me. Ten or 15 minutes and you’re like, ‘All right, where’s the heart and soul?’ I never needed to wear a cape with a capital M on it to show people I am a great musician. It’s not a fucking boxing match. As Mozart said, it’s your brain, your ear and your heart, and if you don’t have all three at all times, if it’s all brain, that doesn’t make the music good.

“Could you imagine Beethoven, who was deaf, certainly by the time he wrote the 9th, 8th and 7th Symphonies and I think they said he was going deaf by the time he wrote the 5th. The music was inside him. He was just writing it pen to paper.

“Bartok, sitting in a room after he was told he was going to die [of leukaemia], and he got the commission for the Concerto for Orchestra. He got the commission, he got inspired, grabbed a bunch of paper and went to a cabin or somewhere and wrote this masterpiece. if you’re not writing from what you hear…”

Then you are writing from what your hands are telling you to do. So it's important to have the musical idea in your head first?

“That’s what the drop tuning did for me. It freed me up from always picking up that guitar and playing that super-comfortable AC/DC riff, because AC/DC riffs are perfect. They’re perfect. You can’t help but pick up your guitar and play them. They’re just so perfect. And then I’ve got the drop-tuning thing going and I couldn’t play anything that I already knew. I had to listen, and I had to write before I pick the guitar up.

“I hear things all the time. I get these Post-It notes and I’ll put down ‘Machine Gun section, Live at the Fillmore East, Jimi.’ I always thought that was so cool, so that is the beginning of Bombastic. And also Jive Talkin', when Barry Gibb plays that [rhythm] and that fucking bass comes in and that Miami sound thing they were going for. Main Course is a masterpiece of a fucking album.”

The Bee Gees were not an influence we’d have you down for.

“So there are different things that inspire you and you hear them and that kind of looms over you. If you listen and then develop that idea into your own idea, and let that idea develop, it is much more conversational. It should be conversational, to me.

“I feel like people, a lot of rock bands and a lot of musicians I know, don’t listen to music. I’m like, ‘What do you do?’ These are friends of mine who are multimillionaire rockstars and they have either lost that inspiration they had when they were 14, 15 or 16 or whenever they got into music and they became rich and it’s about a lifestyle and not a music anymore.

“I have so many friends who can’t wait to get off tour. Can’t wait to get offstage, to just go home. To do what? Sit by your pool? I can’t wait to play my guitar every fucking day. I feel I am just getting started. I really do. This album, because I have been teaching this and preaching this, I am so focused.”

You mentioned Steely Dan there. In among all your influences, was it FM rock that gave you the pop sensibility that we hear in Helmet?

“Yeah, I grew up in the ‘70s and it was on the radio at the time, and it was like Firefall and Orleans, 10CC – ‘So many broken hearts have fallen in the river.’ [The Things We Do For Love]. That music has stuck with me. Then I got into Queen, and Zep.

“I had people saying, ‘You did an acoustic song with a string quartet?’ Yeah, man, I was listening to a shit-ton of Led Zeppelin III and fuck it, I can do an acoustic song, and the tuning was in Jimmy Page tuning because one of my students wanted to learn Friends, that song from Led Zep III. The guitar was sitting there one day and I had forgotten that I had tuned it to that C6 chord, and ‘Wow! This is great!’ I tried it on electric. I tried it on all different things.

“When I was in Memphis to premiere my piece, we went to Stax. I got tears in my eyes. I stood in a room where Booker T and the MGs recorded all that stuff, Isaac Hayes, Aretha. We went to Motown, same thing. I got tears in my eyes. 'Ruffin hung his coat on that hook when he sung My Girl!' That music has always stayed with me.”

And you can be heavy with the acoustic guitar.

“Yeah, absolutely, and Zep is responsible for turning me onto that music. I wouldn’t have known Sandy Denny if it wasn’t for The Battle Of Evermore. Then Sandy Denny, ‘Who’s she?’ I then became friends with Jerry Donahue’s daughter... I got to have dinner with Jerry Donahue, who was a main member of Fotheringay with Sandy. What an incredible guitarist.

“Richard and Linda Thompson, all that incredible music, and I wouldn’t have known about it if it wasn’t for Led Zep. And I wouldn’t have known about Willie Dixon if it wasn’t for Led Zeppelin. I was like, ‘What is this?’ When you are 16 you don’t like that song on the album. ‘This is weird. What is this?’ It’s called the blues, dumb-ass. It’s where our music comes from! [Laughs] ‘Wow! Robert Johnson – that shit is deep.’ It’s so good.”

Music is all about these connections. It’s all the one soup. And the discoveries are never over. There are always new ways of connecting them, like Julian Lage, and how his trio references all kinds of music and takes guitar to this new place.

“I can only dream of being even half of what he is. And Bill Frisell. I’ve seen Bill Frisell a number of times and it’s like, ‘God, he is so creative.’ It’s like he is using distortion and feedback, and electric guitar but clean and then jazz. It is just phenomenal.

“I feel like that is the beauty of being an artist, a musician. I started to feel it when I read Catcher In The Rye, and then I read Joyce, A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man, and Virginia Wolf. You feel this connection. And I feel this connection to Coltrane, like I could feel it when I was listening to the music.

“Whenever I am writing lyrics I am surrounded by poetry books, from Sylvia Plath to Charles Simic, and one of my all-time favourites, Yeats or Pound. It’s connected! We are all in it. The creative thought process? We are on parallel courses. The process is so similar. That’s why I am so fascinated by painters, and I stood when they unveiled [Birth of] Venus at the Palazzo del Vecchio, after they it had been renovated over 20 years or whatever. I stood in front of it for an hour. Or like when I discovered [José de] Ribera at the Prado in Madrid...

“You just feel this power. Those are the building blocks that we are trying to carry on from. So many people want to say this guy or that guy is a genius. Come on, man, he writes rock songs. That’s not a fucking genius.”

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.