Interview: Mike Matthews (Electro-Harmonix founder)

The brains (and heart) behind the fuzz

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

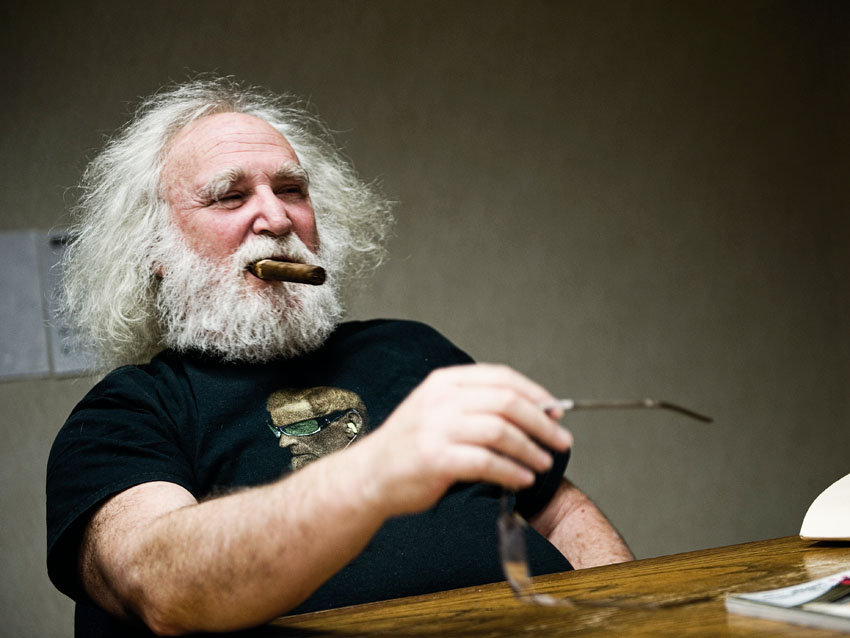

The man himself, Electro-Harmonix founder Mike Matthews in the company warehouse. Image: © Joby Sessions/Future Publishing

Mike Matthews is the larger-than-life founder of pioneering effects maker Electro-Harmonix. He invited Guitarist magazine out to his New York HQ to tell us about the evolution of classic stompboxes such as the Big Muff, his friendship with Jimi Hendrix, and a radical new design of wah pedal that he hopes will rock your world…

It's a cold morning in New York as Guitarist pulls up outside an anonymous three-storey building on the banks of the East River. Ferries plough through the grey waters nearby, while through the drizzle comes a little hint of the mind-bending sounds being dreamt up just yards away inside the headquarters of this sonic institution.

Over the years, guitar effects made by Electro-Harmonix have shaped the sound of some of rock's greatest players: Santana, Gilmour and many others wailed with their classic Big Muff distortion, while The Edge built his early sound around the company's Memory Man Deluxe delay pedal. Overall, it's an impressive tally - and the list of artists making music with EHX effects is still growing today.

Seated at his desk overlooking the New York skyline, founder Mike Matthews punctuates the story of how the company got started with enthusiastic jabs of his big cigar. Sporting a bushy white beard and worn t-shirt, Mike doesn't dress like your average CEO.

After 44 years, he remains so close to the daily management of Electro-Harmonix that he has a bedroom set up in the office, and it's easy to see why he felt stifled by the rigid corporate culture at IBM, where he began his career.

"My first gig after I graduated college was selling computers for IBM around 1965. But as a musician, you get that bug," he explains, referring to his background as a keyboard player.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"After a couple of years I wanted to go out and play again and try to make it big. But I was married and my wife was conservative, so I said to myself, Well, I'm going to have to make some money quick, so she's got some security while I try to make it."

The opportunity Mike was looking for came with the raucous arrival of the fuzz pedal onto the New York music scene in the same year. Its waspish sound was radically different to the smooth clean tones of earlier guitar heroes such as Chet Atkins and Les Paul - and it ushered in a new era of hardcore rock 'n' roll. A born entrepreneur, Mike believed that the booming market for fuzz pedals might provide a way to fund the music career he dreamed of.

The Fuzz Factor >>

The Big Muff is one of Electro-Harmonix's most famous units. Image: © Joby Sessions/Future Publishing

The Fuzz Factor

"The Rolling Stones had a number one hit with Satisfaction," he recalls. "And then all the guitar players wanted to have that Fuzz-Tone sound Keith Richards got. Maestro, the company that made the Fuzz-Tones, couldn't make them fast enough.

"There was this repair technician, Bill Berko, who was hand-making Fuzz-Tones on 48th Street in Manhattan, so I said, Bill, do you want to come in with me? He said okay, but then he dropped out and I was left holding the bag."

Faced with accepting defeat or pressing on, Mike decided to go it alone - holding down his day job while moonlighting as a fuzz pedal manufacturer.

"I took the fuzz design to a contract house in Queens," he recalls. "They'd make a few hundred of these pedals. Al Dronge, the founder of Guild guitars, heard about it and he said, Look, I'll buy all of them.

"By this time, Hendrix was getting big, so Al decided to name them Foxey Ladys. At about 11.30 I'd leave my job, go over to Queens, pick up a few hundred of these Foxey Ladies, bring 'em out to Jersey to Guild and they'd cut me a cheque."

>

Engineer John Pisani discusses pedal design. Image: © Joby Sessions/Future Publishing

Boost For Business

Encouraged by this early success, Mike made contact with Bell Labs electronics ace Robert (Bob) Myer in 1968, and together they set out to design a distortion-free sustain pedal to simulate the soaring lead tones Jimi Hendrix achieved with cranked Marshall stacks. But when Mike visited Myer to try out a prototype, a different device caught his eye instead.

"I looked down on the vice and in front of the sustainer was a little box," Mike recalls. "And I said, What's that? And he says, Well I didn't figure that guitars had such a low signal, so I just built a booster."

Basic yet effective, that linear power booster is still sold today by EHX. Called the LPB-1, it's one of the simpler devices in the company's inventory. Back then, it was a game-changer.

"I plugged a guitar in, hit the switch on the booster and all of a sudden it was loud as hell," Mike recalls. "I said, What's in this? And he says, 'Oh, just one transistor.' Anyway, I stopped futzing with the sustainer because the LPB-1 only had one transistor, it made every amp loud as hell and it was the first thing that drove amps into overdrive. And that was how I got started in the business," Mike says.

>

Mike Matthews holds court in his office. Image: © Joby Sessions/Future Publishing

Hanging With Hendrix

It's ironic that the music of Jimi Hendrix fuelled the explosion in demand for guitar effects that got Electro-Harmonix off the ground. In fact, Mike Matthews played a role in setting Hendrix on his path to fame years earlier, when Mike was an engineering student and Hendrix was a backing guitarist in Curtis Knight's R&B band.

At that time, Mike was working his way through college by promoting gigs, and their paths crossed when Knight appeared on the same bill as Chuck Berry in New York.

"There was this tall, skinny, black guitar player who played these very loose R&B riffs," Mike remembers. "We got talking and started hanging out a lot. He was a loner and I was kind of a loner and I'd go up to his hotel. He had this small room in Times Square that was just big enough for his bed. He'd have his hair set in big curlers and there wasn't even a toilet. But we just talked about music, you know - I like this band, or I like this drummer."

As their friendship grew, Hendrix - who went by the name Jimmy James at that time - explained that he wanted to leave Knight's band and form his own act, which Mike encouraged.

Hendrix left for London in 1966 with Animals bassist Chas Chandler as his new manager. By the time Mike founded Electro-Harmonix two years later, Jimmy had become Jimi and was on his way to becoming an international star. They stayed in touch and Mike recalls that Hendrix was one of the first influential players to use the Big Muff distortion/sustainer.

"By this time, Electro-Harmonix had formed with the LPB-1 and in 1969 we brought out the Big Muff," Mike recalls. "My first customer was Manny's Music on 48th Street. A week later Henry Goldrich [Manny's son] told me that he had sold one to Hendrix, who was in town. So when I went down to the studio to show Jimi a guitar with a built-in ceramic speaker to give feedback, there on the floor of the studio he was plugged into a Big Muff."

Mike says he attended three of Hendrix's studio sessions in New York, before the sheer weight of people trying to get close to the legendary guitarist got out of hand.

"The third [session I went to was for] Electric Ladyland and I stayed for about 15 minutes - but it was so crowded with people that I split," Mike remembers.

>

One of EHX's latest innovations: the Next Step wah pedal. Image: © Joby Sessions/Future Publishing

Next Steps

These days, Electro-Harmonix is a well-established business, but it seems to have kept hold of the independent spirit it started out with, and Mike still likes to innovate.

Following on the heels of their recent Ravish Sitar effect, EHX is set to launch a brand-new design of wah pedal that doesn't have any moving parts called the Next Step, plus an intriguing synth stompbox for guitarists called the Superego, which he hopes will capture the imagination of players. Imagination is key, because Mike says his main priority is to create interesting new sounds and let musicians decide what use to put them to.

"People will find new ways of using things, so we try to make devices that creative musicians can use to set new trends with," he offers confidently. He adds that he prefers to make effects with controls that err on the powerful side, allowing guitarists to explore the full sonic potential of each device, rather than make predictable but sanitised effects with a limited degree of user-tweakability.

"Too many digital pedals crimp and filter the noise to the point where you're just not getting any feeling out of it. In the past, with a lot of our top products, you could turn a pot and if you turned it up too high it began to oscillate," he comments. "But sometimes - right near that oscillation - we get some of the most unusual sounds. A lot of our competitors will take that out. But we leave it in."

When we ask, as an aside, how his pedals came to have such evocative names, such as the Electric Mistress flanger and the Screaming Bird treble boost, his answer sums up the blend of improvisation and pragmatism that has kept the company loud and proud for four decades.

"Most of the names I thought of, but if somebody's got a better name or doesn't like it, I'll use that," Mike explains.

"But you know what, you can have a great name or you can have a simple name, but after a while everybody gets used to it whether it's lousy or great. It's just a name. What it really boils down to is whether the product is good.

"Does it sound great? Does it leave headroom for the musician to express himself? Because that's what music is: it's about expressing feelings."

>

Guitarist is the longest established UK guitar magazine, offering gear reviews, artist interviews, techniques lessons and loads more, in print, on tablet and on smartphones

Digital: http://bit.ly/GuitaristiOS

If you love guitars, you'll love Guitarist. Find us in print, on Newsstand for iPad, iPhone and other digital readers