Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

That Martin Scorsese, director of landmark blood thrillers such as Mean Streets and Goodfellas as well as roiling character studies like Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, would be drawn to the life of "the quiet Beatle," George Harrison, is, on the surface, a little surprising.

Not that Scorsese hasn't been one of our most musically driven directors: From the opening drumbeat of The Ronettes' Be My Baby in Mean Streets to his poetic use of the piano outro of Layla in Goodfellas to his hypnotic bending of Gimme Shelter in The Departed - to say nothing of tackling the movie musical form in New York New York, as well as training his lens on subjects like The Band (concert film) and Bob Dylan (documentary) - his works have always flowed like brilliantly realized concept albums.

But the director has, until now, focused on central figures motivated by outer rage and torment - their conflicts were practically etched on their faces. George Harrison was not such a person, and thus presented a new kind of challenge. John Lennon said it best when he observed that "George himself is no mystery. But the mystery inside George is immense." That's tricky territory to base a film on; it means going inside the soul.

Masterfully, that's just what Scorsese does during the course of George Harrison: Living In The Material World, an elegant and tenacious three-and-a-half hour examination that goes far beyond mere rock-doc hagiography and becomes a rich and absorbing personal odyssey, ultimately revealing itself as an epic, multi-layered love story - that of a man and his music, his famous bandmates, his many and varied friends, his women and, most significantly, his yearning to answer life's big questions.

The scale of the narrative is massive - the tale of The Beatles alone has been told in The Beatles Anthology, a 600-minute Ken Burns-like series, along with libraries of books - but Scorsese neatly divides the film into two parts. Part I covers Harrison's life up till the dissolution of The Beatles in 1970.

Part II, which is, in many ways, the livelier and more revelatory section, traces Harrison's emergence as a solo artist and bookmarks the key historical moments: his rousing success with All Things Must Pass, the Bangladesh concert, his wobbly 1974 tour, financing The Life Of Brian and forming Handmade Films, the Traveling Wilburys. Fittingly, it goes inward, exploring Harrison's fascination with gardening and his desire to make his estate, Friar Park, a world unto itself, a serene retreat. But the bulk of Part II - and Scorsese weaves this thread in minute, almost subliminal ways - concerns Harrison's need to understand his faith and gradually prepare himself to leave his human body.

None of this, it should be stressed, is a downer - there are moments of laugh-out loud hilarity throughout - and even at 208 minutes, the film breezes by. Scorsese makes astute use of new interviews with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr (watch out for Ringo here - his stories are among the best), along with comments from those who knew Harrison and worked with him, a disparate lot that includes, among others, Eric Clapton, Phil Spector (looking quite unhinged - yikes!), Klaus Voorman, Ray Cooper, Terry Gilliam, Jackie Stewart, George Martin and Tom Petty.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

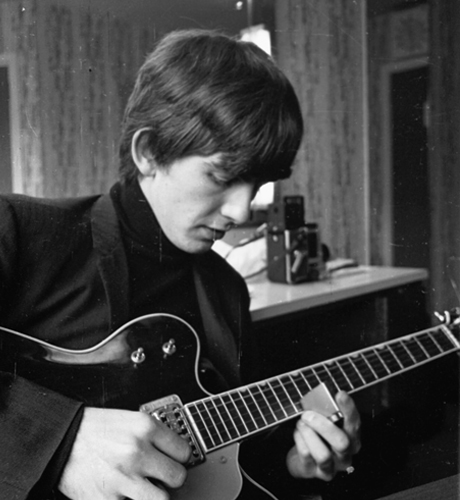

Photo credit: Dezo Hoffman (c) Apple Corps Ltd Courtesy of HBO

The picture that emerges of Harrison - and it starts early in Part I, in something of a warp-speed retelling of The Beatles' story - is that he felt trapped by fame and money from the moment he hit it big. Throughout the years, we've seen endless clips of screaming, crying masses at Beatles concerts and appearances; even hysterical, the throngs always seemed joyous and celebratory, innocents pouring their hearts and lungs out in total devotion and adoration.

Scorsese gets what Harrison no doubt really experienced: the shock and horror of hands tugging at him and ripping his clothes, the pushing and shoving, the claustrophobic feeling that can occur even when on stage on a baseball diamond, and the maddening, disorienting ring of non-stop shrieks. No wonder The Beatles, and Harrison in particular, sought escape.

For a time, Harrison tried to find it in the new music he discovered coming from Ravi Shankar - the guitarist befriended the master sitar player and studied the instrument assiduously. Then he became enamored of the Maharishi, Eastern religion and chanting (the latter two would stick). By the end of the '60s, a decade The Beatles defined, Harrison was becoming his own man, an equal to Lennon and McCartney, and the only way to achieve a true balance in his life was to run past those he used to follow.

During an interview segment taped when he was in his 40s, Harrison says, "People say I'm the Beatle who changed the most, but to me, that's what life's about." This statement, a black-and-white, direct summation to a gargantuan topic, is what plays out during the second and final chapter of the film - and in true Scorsese-ian fashion, it replays and comes together in one's head long after the movie is over.

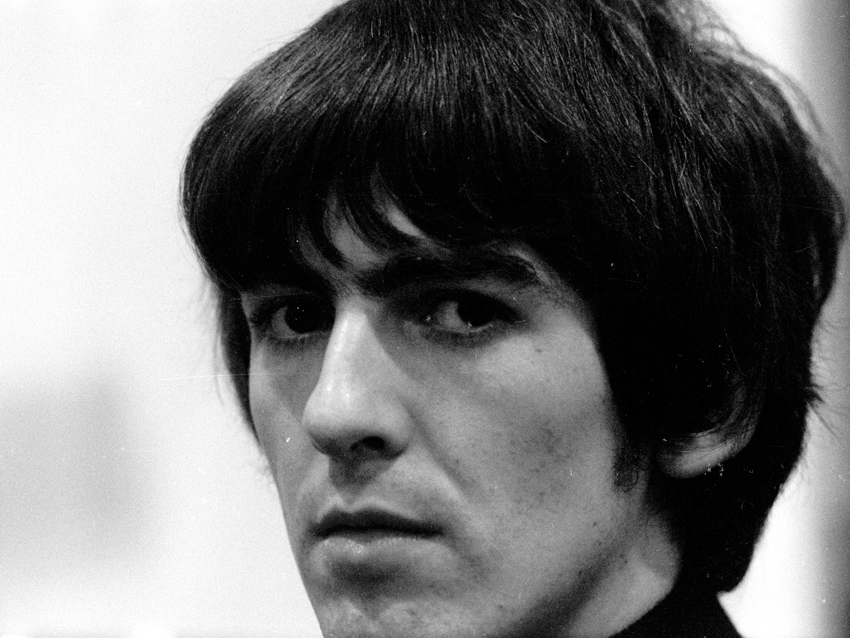

Photo credit Robert Whitaker (c) Apple Corps Ltd Courtesy of HBO

Despite the involvement of George's widow, Olivia Harrison (she co-produced and is interviewed), Harrison's foibles and inconsistencies are addressed. Without elaborating, McCartney talks about Harrison's fondness for the female form: "I don't want to say much, because he was a pal, but he liked the things that men like. He was red-blooded."

Perhaps more tellingly, Olivia talks of "hiccups" in her marriage to Harrison: "He did like women and women did like him," she says. "If he just said a couple of words to you it would have a profound effect. So it was hard to deal with someone who was so well loved." When asked to name the secret to a long marriage, she laughs and says, "You don't get divorced."

Before Harrison met Olivia, he was first married to fashion model Pattie Boyd, and the subject of the love triangle between Harrison, Pattie and Eric Clapton is dealt with cautiously. During an interview, Clapton weaves artfully around the topic, and Harrison's reaction to the fact that he was losing his wife to his best friend is depicted somewhat inconsistently. "Take her, she's yours," Clapton says Harrison told him at one point, but when Harrison found the two together at a party he was overcome with anger.

The idea of having everything and nothing at the same time drives Harrison throughout the final reels, and little by little he appears to find fulfillment in the smallest of ways - planting a tree, playing a ukulele or singing an old song. The 1980 murder of John Lennon shook him to the core, and it was this event coupled with his bout with cancer and his 1999 stabbing that accelerated his greatest journey: mastering the art of dying.

From all accounts, he got where he wanted to go. In two of the most moving interview segments, Ringo Starr recalls his last time seeing his old friend. Harrison was bedridden, riddled with cancer, and Starr told George that he had to go to Boston where his daughter was receiving treatment for cancer as well. "Do you want me to come with you?" Harrison asked weakly. Retelling this line, the drummer's eyes well with tears. "God, it's like fucking Barbara Walters here, isn't it?" Starr says, drying his eyes.

Olivia describes Harrison's last breaths, and says that the room took on a glow when her husband died, that a truly magical moment took place. The awestruck look on her face, the astonishment and profound relief in her voice, makes a convincing case that this is not revisionism or embellishment.

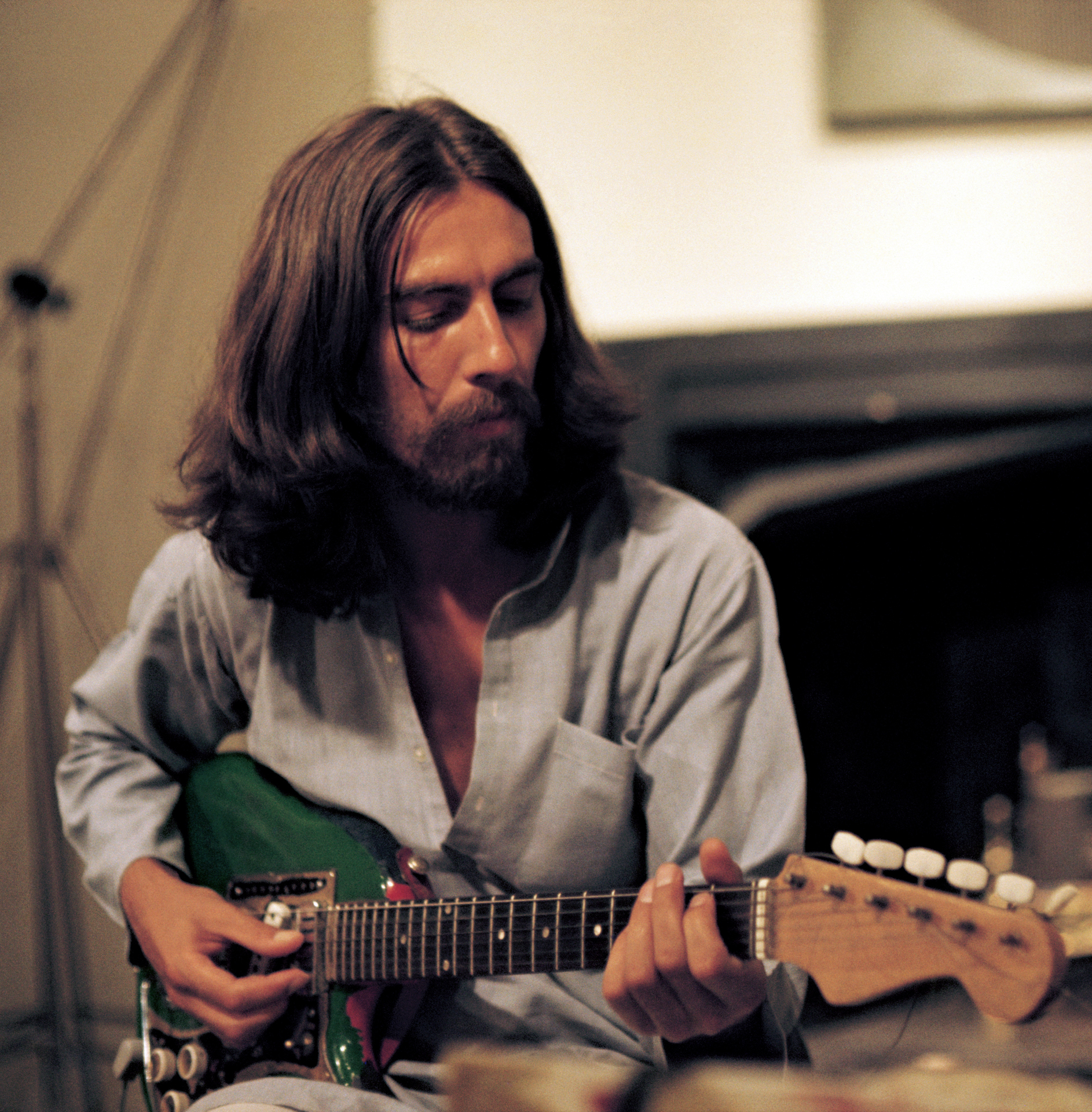

Photo credit (c) Apple Corps Ltd Courtesy of HBO

Of special interest to Beatles and George Harrison fans are the music and the visuals, and they're all presented in the sumptuous manner endemic of a completist like Scorsese. Many of the photos and film clips have never been seen before, and the dozens of Fab Four and Harrison songs have received a vibrant 5.1 audio remixed by George Martin's son, Giles.

Guitarist, follower, leader, student, teacher, songwriter, sitar player, multi-millionaire, mystic, gardener, race car enthusiast, film producer - George Harrison was all of these things and more, a true original in a band of true originals. He would refine his role as an individualist throughout his rich and varied life.

George Harrison: Living In The Material World will receive theatrical showings in the UK on Tuesday, 4 October. It will be available on DVD and Blu-ray on 10 October. In the US, the film will be presented on HBO in two parts, on Wednesday, 5 October and Thursday, 6 October.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.