Donal Gallagher: “Playing with Muddy Waters was Rory’s badge of honour”

Rory Gallagher's brother and manager on his blues roots and celebrity fans

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Rory Gallagher was the original Irish guitar hero - but his playing was deeply rooted in the rich soil of American blues, which he studied from boyhood.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of his recording debut, a treasure trove of previously unheard tracks sheds light on his rare gifts as a player and lifelong disciple of the blues. We lift open the cases of some of Rory’s best-loved guitars to learn how they helped him transport listeners a million miles away...

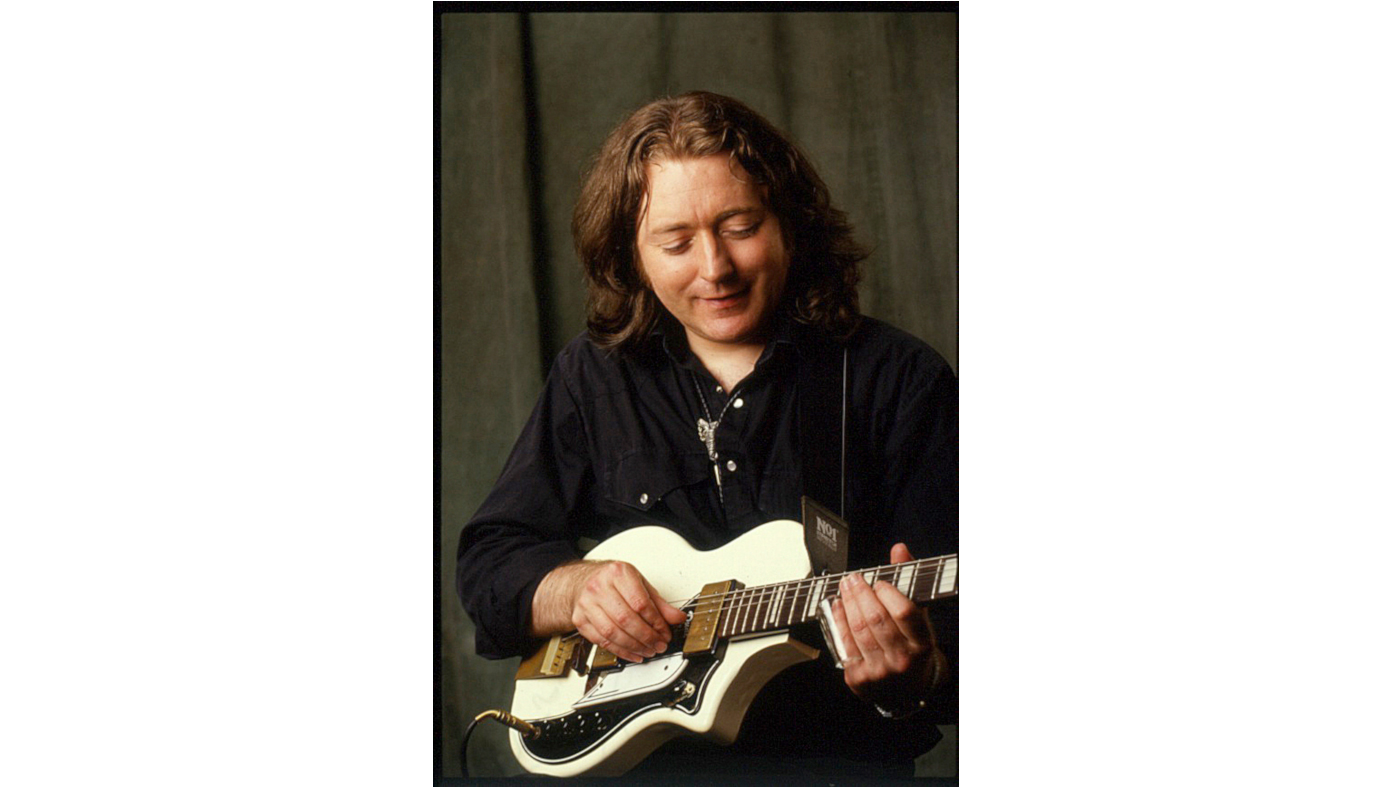

When the guitar world learned of Rory Gallagher’s death in 1995, he was mourned almost as one might a friend, even by those who only knew him through his music. At 47 years of age, he was too young to leave the stage with such finality.

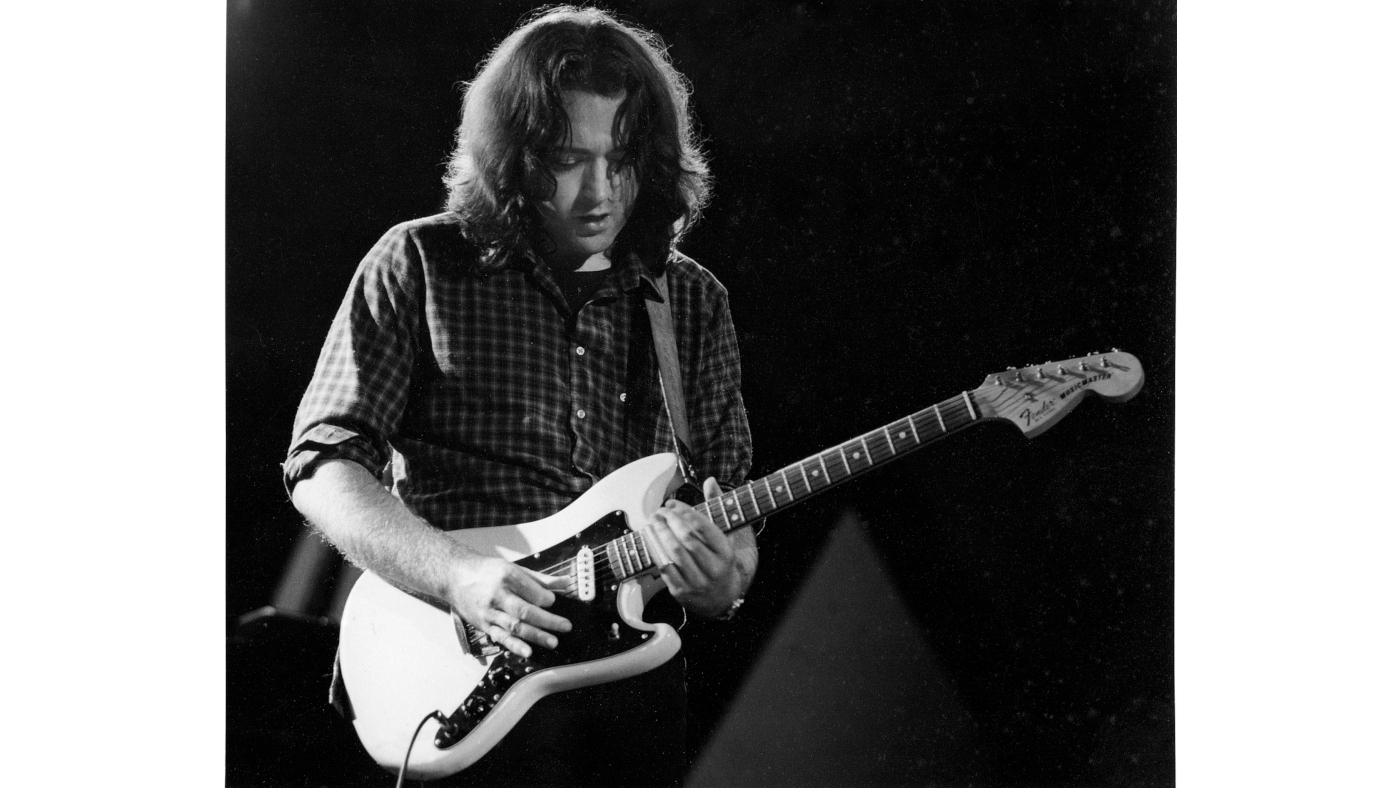

Witnesses to Rory’s electrifying live shows knew what a formidable performer he was - coming back for encore after full-tilt encore, letting fly with his battered ’61 Strat as long as the crowd cheered and stamped their feet for more. It was all the more saddening, then, that there could be no more curtain calls for a man who was humble by nature but whose guitar playing was loved by millions for its ecstatic energy and unaffected eloquence.

Rory was also a prolific recording artist and left behind a back catalogue as thick as a phone book. Like the wheels of his tourbus, the tape was always rolling, so there was always going to be more to be discovered in the vaults. Now, on what would have been the 50th year of his recording career, Rory’s family has unveiled a host of previously unreleased recordings, all linked by his lifelong love for blues guitar.

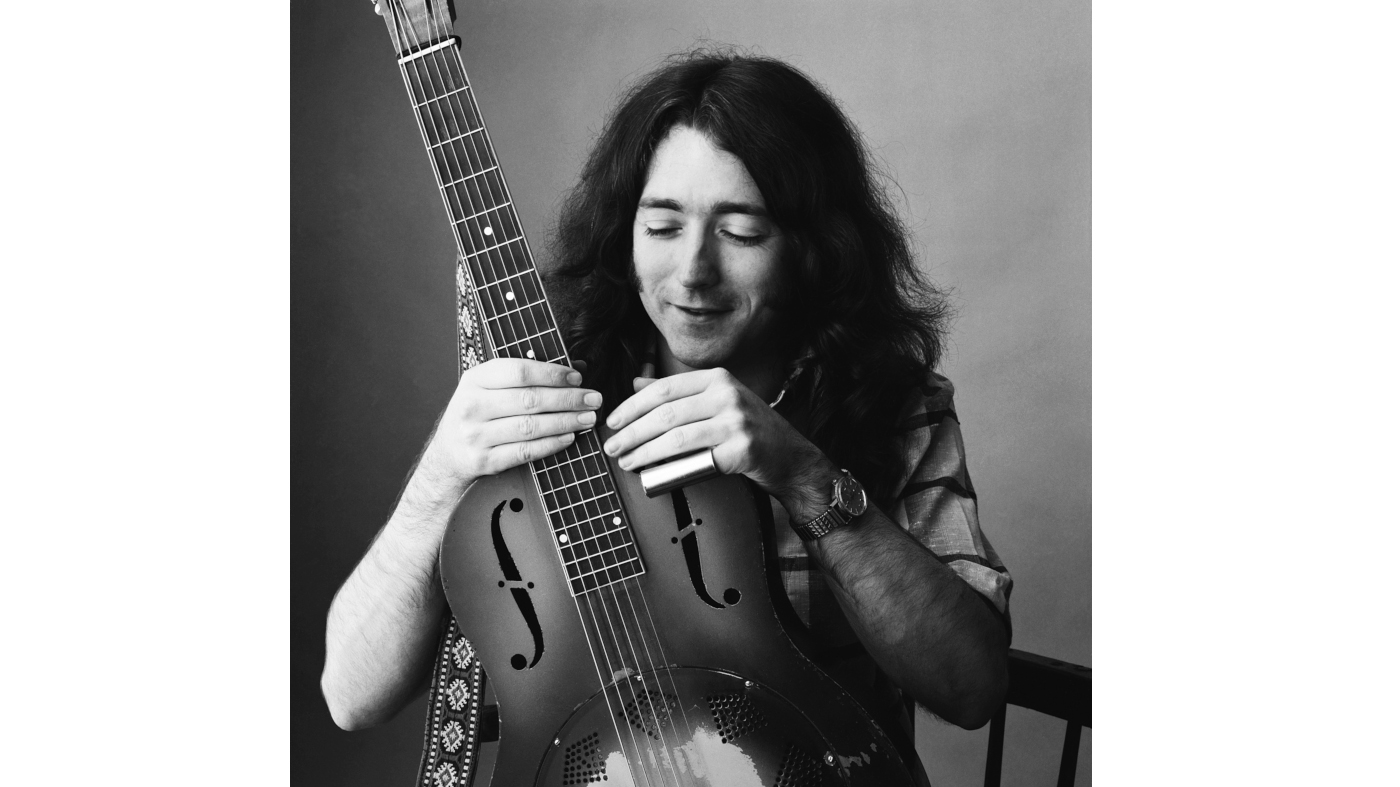

More than 90 per cent of the tracks featured on the new 36-track collection, entitled Blues, are previously unheard. Some show off Rory’s haunting affinity for old-time country blues, played on his National resonator, while others are full-flight rockers that send showers of sparks flying with every incandescent slide lick.

The collection also documents rite-of- passage encounters between Rory and the American bluesmen who’d been his childhood heroes, like Muddy Waters and Albert King.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It’s an occasion worth marking, so we take a close look at Rory’s best-loved guitars to learn how each earned its place in his extensive collection - and discover how he used them to craft songs that still leave listeners spellbound today. But first, we join Rory’s brother and long-time manager, Donal Gallagher, to hear how Rory grew from a boyhood blues disciple to a master of its many forms...

Blues base

When did Rory first show an interest in blues guitar?

“I remember it as being when we were living in Derry, in the north of Ireland. We were in the Bogside, which was where my father came from. That was just post-war, and the Port of Derry had been given over to the American navy. That was their base for Europe, which had been through the Second World War, and the Americans had lingered on because of the Cold War.

“They had built a massive antenna to transmit AFN [American Forces Network] radio and, basically, the early radios couldn’t keep out the signal. Sometimes the radio was almost on without it being switched on. When my folks would go round to visit the neighbours - because it was one of those sorts of streets - Rory would get out the radio and dial up the station.

Guitars weren’t in. It was really only when The Dubliners came along that a guitar was seen with a folk band in Ireland

“He’d somehow gotten the schedule of the programs, because I remember he’d tune in for the Jazz Hour. It was like an obsession for him. I mean, it used to freak me out because of the introduction to it, you know? The big deep, baritone voice was like the Devil coming through the radio saying, ‘This is the Voice of America... The Jazz Hour.’ It was so trippy and abstract that I’d run out of the room, but Rory would listen to the jazz.

“But during that program they would also introduce some blues music. I can’t be specific as to who the blues players were, but I guess it would be very early Muddy Waters and stuff like that. There was also a parallel to that on the BBC, which was the World Service. Once a week, you’d got the Chris Barber jazz and blues show, and he would introduce guys like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee as guests on the show and, of course, Lonnie Donegan. They’d do their little skiffle set in the hour.

“These were the initial places that Rory fed off for the blues. Then we moved from Derry down to Cork City. He’d go in and grab books out on the blues at the library there... anything that referenced blues music. I suppose he saw parallels with the traditional music in Ireland and, coming from the background that we were coming from, there was a growing civil rights movement as well.

"So he’d sort of taken blues on as his adopted music.”

Was Rory learning primarily by ear, from records, or was there anybody locally who taught him how to play blues guitar?

“No, it was entirely by ear with Rory. I do remember him, once he got a wooden guitar for the first time, taking it over to the School Of Music in Cork and asking if they’d give him lessons. They politely said, ‘Oh, no. You have to learn the piano first and then you can learn the guitar.’ They didn’t see it as proper instrument, you know? Guitars were a rarity. They weren’t a common thing.

“When Rory was trying to express himself to my parents, as to what he wanted, they were very confused. Was it a banjo? A banjo would have been more in the traditional Irish idiom. Guitars weren’t in. It was really only when The Dubliners came along that a guitar was seen with a folk band in Ireland. It was a new breed of thing.

“I remember the first time he was trying to tune a guitar, and this customer in my grandmother’s bar offered to do it for Rory - and broke the string. What a catastrophe! It was, like, ‘That’s going to cost the price of the guitar to replace, almost,’ you know.

"So, across the road we had this pal, and his dad had an ice-cream parlour. He was a violinist and he used to tune Rory’s guitar for him, very precisely, which was quite a task. So, it really was a novelty to have a guitar.”

Sliding scale

How did Rory’s slide playing develop?

“It was there around the start, because of Hawaiian guitar... He’d read that they played with bottlenecks, so he was always going through the empty bottles in my grandmother’s bar to look for bottles that might be suitable. But they all had big lips on the top of them, so you couldn’t quite use them.

"That’s curious to me, because [playing slide] meant a different tuning and tuning the guitar was an art in itself just to get it right.

“He studied so much, though. In a sense, I lost my brother once he’d got so devoted to learning all the various chords. I remember, after getting his initial chord book, he was already down to the piano company, getting his next one.

"He’d gone from the majors, the minors to the flattened D7 [sic] and what have you - I mean, that’s where I lost interest, to be honest!

He seemed to take it in huge bites, you know? His progress was so rapid at that point

“This would have been when he was around 10 or 11. He’d come in from school, lock himself away in the bedroom and that was it. He didn’t come out to play football anymore. I’d go off with the other pals, or whatever. He seemed to take it in huge bites, you know? His progress was so rapid at that point.

“It was a very modern route that he was taking because, obviously, music around the world was exploding with Bill Haley, then Elvis and Lonnie Donegan. There were so many different ways to go. Then the Shadows came through with their Strats and that was another thing. But he was sticking very much to the blues.”

The new record, Blues, sees Rory pay tribute to Peter Green on the track Leaving Town Blues. What did he think of the British blues trailblazers like Green, Clapton, Beck and Page?

“He felt a huge connection to them. I mean, Rory’s first exposure to that music came via The Yardbirds. Rory would have gone to London around 1965. In the black days of Ireland, when Lent came, ballrooms were shut by the church, so there was no dancing or music and all the work dried up, because if you were a professional band you couldn’t be seen to be [performing] around town.

"That’s the way they felt back then and so musicians would go to the UK, to play the Irish dance halls in North London, Coventry and Birmingham. And they’d get enough work to keep them going through the six weeks of Lent.

“That gave Rory the opportunity, staying in a B&B in London, to go down to [influential Soho music venue] The Flamingo. I remember, he’d write to me and say, ‘We’re seeing Steampacket and John Baldry,’ and, obviously, that had an amazing line-up of Elton John on piano with Rod Stewart on vocals. Another time, he was out in Hamburg and I remember him writing a card saying he’d gone to see Cream at the Star-Club, and had a very pleasant conversation with Jack Bruce afterwards.

“By the time Rory had cemented Taste into position, he had gone up to Belfast in ’67, and was resident there. His then-new manager was the agent for Robert Stigwood. He’d bring various bands from the UK across, so you had John Mayall, of course, and we would do about a week’s worth of gigs around the north of Ireland. At that time, that would have been Mick Taylor on guitar. So there would be friendships and conversations.

“Then Cream came over, and Taste were due to support Cream at the Ulster Hall. But the gig got cancelled because Cream pulled out. They came back a few months later and did three shows in the north of Ireland. I mean, they were in the oddest places. One was a ballroom in Portstewart, so they were playing a seaside town in the winter and everything that goes with it.

Free as a ‘Bird

“So there were links and contacts that grew from that. And then Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac came over - and, yes, Rory would have been very taken with Peter’s personality. Some of the guys would have a very cocky attitude, but Peter didn’t and he was very good. In fairness, Rory’s ambition was to get a gig at the Marquee and it was very much a word-of-mouth scenario back then, you know, so [if you had a good reputation among other leading bands] you’d get a trial.

"Then, as that kind of music broke out into Europe and beyond, we ended up doing festivals. Very gratefully, we also ended up doing the two shows of the Cream farewell concert at the Albert Hall along with Yes. So all that gave Rory his first opportunity to get to the stage with Taste.

We also ended up doing the two shows of the Cream farewell concert at the Albert Hall along with Yes

“Rory adored anyone who could play guitar. Jimmy Page was another favourite of his and Rory would send me postcards from America saying, ‘Oh, we’ve supported The Byrds...’ and so on. Meanwhile, back in Ireland, I’m stuck taking my American aunt down to Shannon airport, as she was going back to the States.

"While I was waiting at the airport, the doors opened and in walked these guys with long hair, who I thought were The Byrds - they looked very similar. But it was Keith Relf [of The Yardbirds], and they were on their way to America for the first time. I went up and said, ‘Excuse me, are you The Byrds?’ and they thought I was being really hip and said, ‘Hey, man, how did you know we’re The Yardbirds?’

“I just said, ‘Oh!’, and then I counted them - because I knew who The Yardbirds were - and I said, ‘But shouldn’t there be five of you?’, because I was getting their autographs, and they said, ‘Our guitar player left last week.’ That was Eric Clapton. I was looking for his autograph, and they said, ‘Oh, but we’ve got this really amazing new guitarist, Jeff Beck. He’s in Duty Free. Once he comes out, we’ll get you his autograph. You’ve really got to check this guy out...’

“The layover they would have had would have been a couple of hours, maybe, while they refuelled the plane. They felt very alien, I think, in the west of Ireland. They were astounded that somebody had actually heard their records, and knew For Your Love. So I wrote back to Rory and said, ‘Guess who I met?’”

Fresh Waters

Tell us about the session that Rory played on with Muddy Waters. That must have been quite a big moment for him...

“Oh, absolutely. That was Rory’s badge of honour. We’re talking ’71 there. Taste split up at the end of 1970, so Rory was out trying to re-establish himself as a solo artist. We were up in Leicester at the De Montfort Hall. So Rory gets the call: would he play guitar? He said, ‘Yes, I can do it, but I have a gig in Leicester.’ So they said, ‘Oh, well, the session wouldn’t start until the evening anyway.’

Muddy Waters was so genial and polite, and no pressure whatsoever, you know

“So, Rory is on stage at the De Montfort Hall and the session was starting at 10pm, but with maybe an hour’s leeway. Of course, as an American promoter used to say to me, ‘You know, your brother never threatens you with not going on stage. He threatens you with not coming off.’ The next thing, it’s 10.30pm and he’s still on his fourth encore, or something, and I was at the side of the stage going, ‘Rory!’

“Eventually, he comes off the stage and he jumps into the car, which was the old Ford [Zephyr] Executive. I mean, it was boot-to-the-board to get to the session. In fact, we drove so fast that the following day I found that we were running on the canvas; the tyre had actually eaten itself away with the speed we were doing on the way down.

"In the end, it must have been after 11pm when we got to the session. Rory thought, ‘I’m going to be fired from this,’ and he was getting, ‘You’ve only yourself to blame,’ sort of thing [from me]. But when he got in the door, Muddy just poured out a glass of champagne for him. Rory was all apologetic, but Muddy was saying, ‘That’s what musicians do. They work at night time. So, don’t worry about it. Relax. I want you to enjoy the session.’ He was so genial and polite, and no pressure whatsoever, you know.

“That first night went great. There were no record company people there on Muddy’s behalf, though. It was very much Muddy and the band. They were in a hotel in Kensington, as I remember, and there were a couple of nights off and they didn’t seem to know where they were.

"There was no-one to take them out, so Rory sort of dispatched me to drive Muddy. Muddy travelled in [our] Ford and loved the car because it was, as he described it, the first American-style car he’d been in in Europe. It wasn’t too long after the accident he had, so his leg was a bit lame, and he could stretch it out in the Ford.

“I remember taking Muddy and the band down to the old Speakeasy on their night off and at the time being a bit apprehensive about who the Speakeasy might allow in, or not allow in. I went down in advance and they said, ‘Muddy Waters is coming down here?’ It was fantastic. So Muddy came down, and then, of course, all the musicians in the club swamped him and the band, you know. A wonderful couple of days.”

Dylan diversion

Rory’s affinity for traditional roots blues guitar was really quite amazing - particularly on I Could’ve Had Religion from the new record. it sounds like Son House or something...

“Well, oddly enough, there’s a story with that one. Around the period of Fresh Evidence - I’m talking late 80s and early 90s - I got a call from Bob Dylan’s office, who told me he was looking for a CD version of Live In Europe, and it seems he couldn’t buy it in America. Now, that surprised me at the time, but I was delighted that [Bob Dylan] was looking for the CD, and I actually sent Fresh Evidence out to him as well, which was Rory’s latest album at that time.

"They came back and said Bob was doing an acoustic album of traditional blues songs, and that he was intrigued by I Could’ve Had Religion and he wanted to listen through to Rory’s version. So I thought, ‘Great.’

To be put into the blues musicians’ category would have been Rory’s triumph

“But when Dylan’s album came out [Good As I Been To You, released late-1992], I remember feeling kind of disappointed that the track didn’t appear on it. This is now ’93 and we were on tour in Germany, and that [album] was the only thing that was played in the car.

"Rory kept playing that album over and over again. He’d fallen in love with it. Then I got a call from Montreux. It was Claude Nobs [founder of Montreux Jazz Festival] saying, ‘Oh, I have a great idea. I’ve got Bob Dylan - how about Rory and Bob Dylan on the one bill?’

“On the night, Dylan decided that he’d open the show, then Béla Fleck was the in-between artist, and Rory would close. That’s the way Dylan wanted it. In between the sets, he came up to say hello to Rory, because they had met previously, in Los Angeles.

"So, anyway, Rory and Bob were in the dressing room.... having this wonderful chat about [Dylan’s] kids. And I’m, kind of thinking, ‘Hang on, where’s the musical conversation going?’ Rory was going, ‘How’s Jesse doing?’ I mean, he knew all the kids’ names. But then as Bob was leaving, I said, ‘By the way, I’m glad you got the Live In Europe album, but I Could’ve Had Religion... you didn’t do it in the end?’

"And he said, ‘Oh, Rory had me fooled with that song. I thought that was an old traditional song that had got lost. It was only when I listened that I realised you wrote that whole section.

“Rory said, ‘Yes.’ And Dylan said, ‘Well, you should have put it down as a Rory Gallagher title.’ But Rory said, ‘I couldn’t do that.’ So Dylan said, ‘Well, where did you find the song to begin with?’ and Rory said, ‘I found it in a book of poetry, but it was uncredited. It was just called I Could’ve Had Religion. It was just one verse. I expanded the song from that, and worked on it.’

“So Bob said, ‘The thing was, after listening a while and checking other sources, I realised you’d written it, [otherwise] I would have done it and put it down as ‘Bob Dylan/Traditional’. But, in fairness, I couldn’t do that to you.’ So, there you go.”

Do you think that Rory saw himself primarily as a blues guitarist?

“I suppose it was ‘musician’ first. The word ‘musician’ was completely key since he was a kid. You know, if someone said to him, ‘What’s your job?’ or, ‘What are you going to do when you grow up?’, his answer would always be, ‘Musician’.

"His life was about perfecting his musical ability, whether that meant the studio skills or learning other instruments... To be put into the blues musicians’ category would have been Rory’s triumph, if you like. It didn’t matter what colour you were - black, white or green, you know?

“Blues music is emotional; it’s soul music, obviously. You hear the melancholy in traditional Irish music, and Spanish music, and the Fados of Portugal, in French music. It’s that melancholy that comes through the DNA and into the fingertips.”

Blues by Rory Gallagher is available now on UMC in three formats, including a 15-track one-CD/two-LP version, a limited-edition blue vinyl two-LP set and a deluxe 36-track three-CD version showcasing Rory’s virtuoso performances of electric, acoustic and live blues respectively.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.