Everything you need to know about Dolby Atmos and Spatial Audio - plus 10 unmissable Spatial Audio in Dolby Atmos tracks, and 3 to avoid…

RECORDING WEEK 2023: What’s all the fuss about and do you need to upgrade your streaming service and throw out your stereo? We explain all

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

RECORDING WEEK 2023: Every few years, the audio industry likes to reinvent itself, invent a new format that’s ‘better than ever’ and perhaps coax out a little extra cash for something you already own.

The current modern miracle for listening to music is in surround, with Dolby Atmos being the format of choice. Now music sounds bigger, it comes from all around you, but does it sound any ‘better’? And just what do you need to hear the difference anyway?

Now music sounds bigger, it comes from all around you, but does it sound any ‘better’?

We’re here to tell you everything you need to know to best enjoy Dolby Atmos music (including Spatial Audio with Head Tracking on Apple devices), to explain the science behind the sound and decide whether the whole upheaval is really worth all the hype.

And we’ll round that out with 10 tracks where we think you’ll love the difference that a little Atmos can bring… and three tracks where you won’t.

Surround, Atmos, Spatial?… What’s all the fuss about?

The fuss is about an exciting new way to listen to music. An opportunity to reengage with music you love and hear it in a whole new light. And to present a new avenue for new music to sound more arresting and higher fidelity than music ever did before.

An audio engineer explains why Dolby Atmos Music is “definitely going to supersede stereo”

And – let’s be honest – to record companies and music publishers with a long-running reputation for reworking, repackaging and reselling you the music you already love, the sound of a new format requiring new purchases and subscriptions (and quite probably the purchase of new gear to play it) is pure music to their ears.

Multiple speaker setups found favour in the cinema and subsequently the home cinema, recreating the sound of off-camera action zinging past the listener, thereby ‘immersing’ them more believably in the depiction on the flat screen in front of them.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Dolby Pro Logic begat Pro Logic II, went digital with Dolby Digital 5.1, then 7.1 and now hits a whole new level of fidelity in Atmos, which can be delivered via more channels, in more places and at greater quality than ever, to the extent that it’s debatable as to whether any audio application will ever need ‘more’ than Atmos.

What do I need to listen to music in Dolby Atmos?

First you need a source of Dolby Atmos encoded music. That is music that has been mixed specially to take advantage of Dolby Atmos, expanding the familiar two-speaker stereo mixes we all know and love into multi-speaker, multi-directional monsters that can – miraculously – be played on practically any piece of hardware.

Services such as Amazon Music and Apple Music are pushing Dolby Atmos encoded music hard right now as the next big thing. And the good news is, if you’re a subscriber already, Dolby Atmos music has already been magically added at zero extra cost.

How much you invest in new hardware to enjoy it is entirely up to you, but do know that even the most basic of headphones, mobile phones or even ‘mono’ desktop speakers such as Amazon’s Alexa will play Atmos and – if you’re listening closely – you should hear a difference.

You say should hear a difference?

Yeeeesss… Y’see it all comes down to Dolby’s gradual, decades-long realisation that not everybody is willing to throw out their music collection and the equipment that plays it. Far better to create a format that caters for any equipment. From seven-speaker, two-sub, ceiling-mounted home cinema installs, to something as simple as a pair of earbuds. That’s Dolby Atmos.

You ‘should’ hear a difference as – inevitably – the more you invest and the more trouble you go to, the more Atmos gets to stretch its legs and the better it sounds.

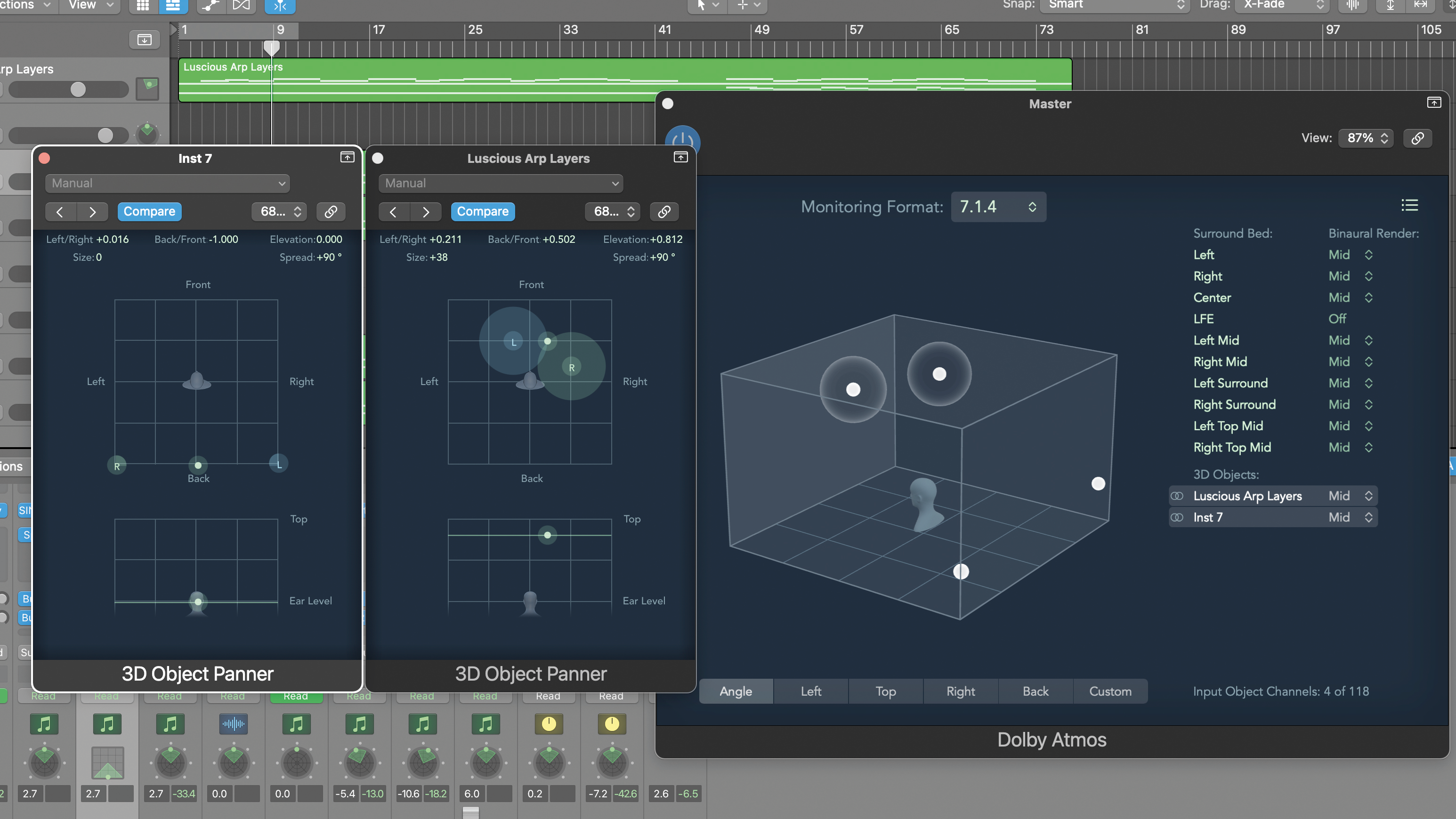

Top of the hill are large, multi-speaker installs. Atmos music is split into multiple tracks (stems) that can be sent to anywhere in a 3D space. This encoded digital signal is then decoded in your home, back into separate channels, with each of those channels driving a separate speaker.

Thus, a sound appears to come from ‘over there’, because it really is coming from ‘over there’. Physical Atmos is therefore amazing but not particularly ‘clever’. In fact, there’s no computational trickery involved at all – it really is just a case of recording/creating the separate channels and playing them back in the right place. Remember, you’ll need a device such as Apple’s Apple TV 4K to convey the digital Atmos soundtrack to your amp.

The clever bit is really in the far simpler and accessible world of ‘virtual’ Atmos and the business of playing back these multiple point sources on headphones. Here, complex algorithms are used to imbue each separate, distinct Atmos channel with all the characteristics of direction and height that were encoded into the multi-speaker feed.

Have you ever considered how it’s possible to know if a sound is in front of or behind you despite only ever having a left and a right ear? You know when a plane is high above you. Or if a car approaching is coming from ahead or behind. How is this even possible?

The answer is because your ear – and we’re talking about the fleshy sticky-out thing on the side of your head here – gently changes and influences the tone of the sound as its waves make their way through its many grooves and furrows into your cochlea (the inside-your-head bit).

It’s a very subtle set of changes, but it's enough to imbue the sound with characteristics that the brain can recognise and pop into a full 3D perception map in the mind. It’s kind of miraculous.

Just as we can tell where a sound is coming from in real life, so Dolby Atmos finely tunes sound with the same characteristics of tone to trick our ears and brains into perceiving a ‘direction’ element along with the sound itself. It’s basically cutting out the hardware and speakers bit and jumping straight to the ‘what your brain hears’ part. It’s spooky. It’s genius. And it works.

So does music in Dolby Atmos sound better?

Be under no illusion. There is a huge element of ‘emperor’s new clothes’ about Atmos, Spatial and surround in general. Some swear they can hear it every time Atmos is toggled on, while for some it never seems to happen. For most it makes music sound ‘different'. But ‘better’? That’s always debatable.

And while we can agree that large, powerful, high-end, expensive systems will always sound better than cheap, poor quality ones, the dividing lines and debate over ‘which headphones deliver the best Atmos’ is a far greyer battle. And while in-ears such as the AirPod line from Apple make a big play of their Spatial Audio as a feature, do remember that you don’t need AirPods to enjoy it.

Any headphones can play Atmos audio (even streaming from Apple Music) and – by and large – larger, better, more expensive headphones will play it better than cheaper ones. That is to say there’s a good chance that they will introduce its nuances more perceptibly than cheaper in-ears.

And considering that one of Spatial mixes’ frequently used ‘wow’ tricks is a boosted bass (or at least a bass that’s clearer and more controlled) it’s common that in-ears such as AirPods (notorious for their lack of real bottom-end) fail to register any kind of difference. Thus, there’s a good chance that most listeners will consider the whole Atmos thing ‘a bit useless’.

So Atmos is clever… But rubbish?

No, we’re saying that a large, physical, multi-speaker system is always best. Failing that, expensive headphones from a thousand brands, taking advantage of Atmos’s built-in, ear and brain-tricking algorithm magic, come second. This includes Apple’s own premium-priced AirPod Max over-the-ear headphones.

In third place are the in-ear products (such as AirPods and AirPod Pros) that are – ironically – the exact medium being promoted hardest to deliver Spatial audio in the first place. They sound fine, but if you want to hear Atmos and Spatial every time, there are better means to get it into your head.

How to integrate Dolby Atmos and Spatial Audio into your music-making

But surround has to be better than old stereo, right?

Not necessarily.

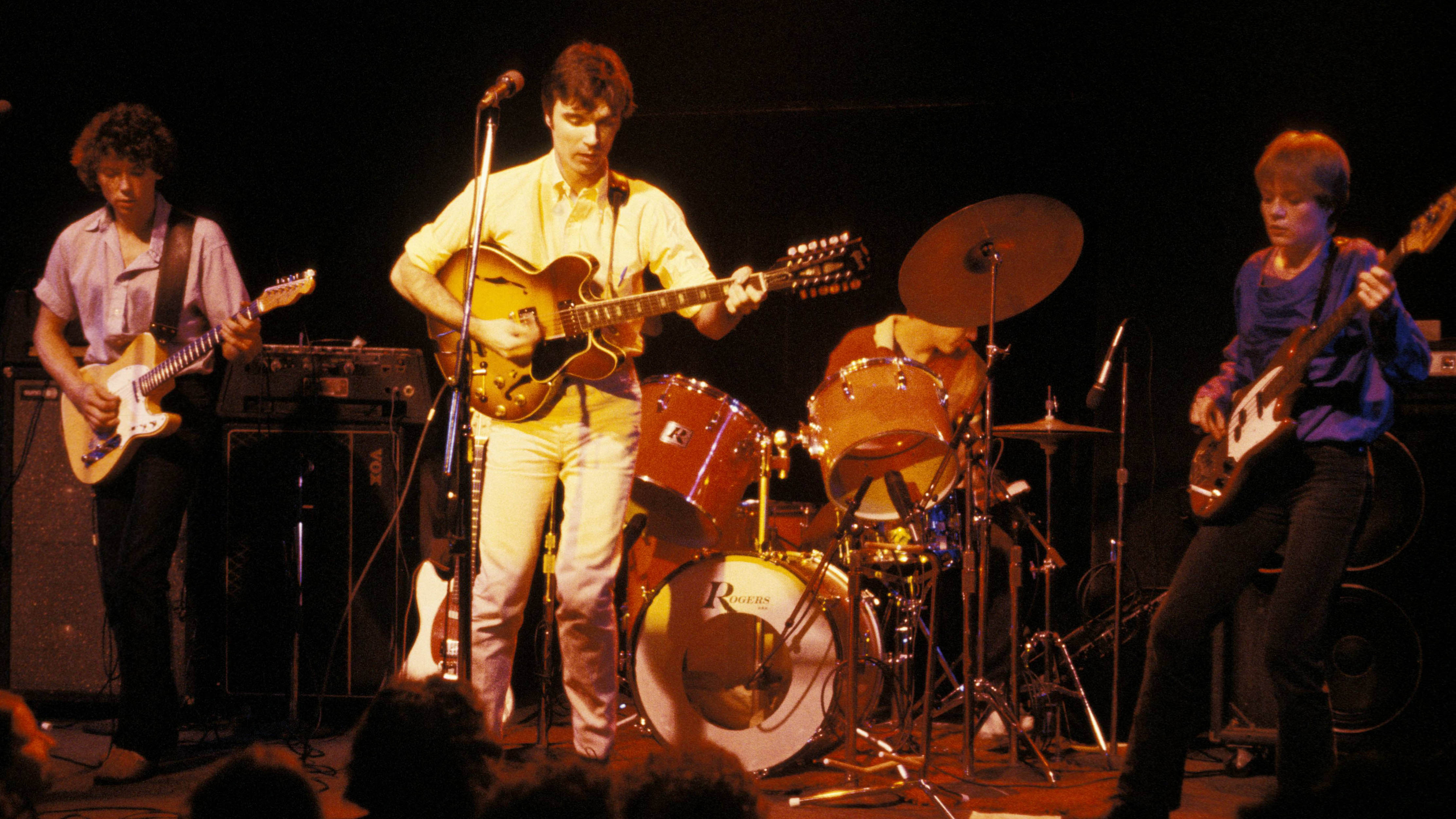

Consider the purest form of consuming music - ie, standing in front of a band while they play it to you. What are we actually listening to? There’s the vocalist, usually in the centre, and perhaps a guitarist or two off to the side. Keyboards, perhaps? Left, or right? And a drummer, again, in the centre, and usually at the back.

So are any of these elements behind you? Or to your hard left or right? Certainly none are above you… Which begs the question: didn’t we nail the recording and playback of music with the invention of stereo? We have two ears and stereo has two speakers – one for each ear. What more do we need?

Yes, stereo nailed the accurate reproduction of physical music in detached (be it in space or time) listening environments. It knocked mono into a cocked hat, which is why it dominates ALL music released on all formats and consumed in all places. Even today’s phones have more than one speaker. The fact is, for reproducing a soundfield in front of a listener (ie, reproducing the effect of you standing in front of something making a noise) stereo is perfect.

So what’s Spatial Audio? Is that Dolby Atmos too?

Apple calls what they deliver via Apple Music ‘Dolby Atmos with Spatial Audio’, then shortens it to Spatial Audio (while using the Dolby logo as an indicator that a track is encoded with the format on board).

The exact combination of Dolby and Apple tech being used is typically hidden behind Apple’s quest for simplicity, but suffice it to say that Atmos is doing the clever stuff and Spatial Audio adds Apple’s unique, only-on-certain-AirPods Head Tracking trickery.

Head Tracking in AirPods senses the movements of your head so sound can remain ‘stationary’ within a space allowing a listener to move around it. Even if you’re wearing headphones, the sound, rather than moving with your head – as per every other time you’ve worn headphones until now – appears to remain stationary as if coming from speakers rather than being fixed to your ears. Thus, surround sound on headphones finally ‘surrounds’ you, allowing you to move around it physically.

It’s certainly a very clever effect and has some merit when watching TV or movie content – if you move or turn away from the screen and the sound moves and turns away from you too (even though you’re actually wearing headphones that are blasting it into your head).

But for music? If you’re one of the tens of millions of people who listen to music while walking down the street, commuting, or exercising then the Head Tracking aspect of Spatial Audio could be a huge distraction. With Head Tracking ‘on’, the sound ‘swills’ around the stereo field as you bowl down the street. Tracks drift and separate, creating confusing smears on the music you love, before gradually coming back into focus when you stop moving.

Head Tracking can be a weird distraction that endlessly skews the mix as you go about your business. We say that in anything but static, seated listening, Head Tracking is to your ears what being trapped in a capsized canoe is to your eyes.

So how do I best enjoy Apple’s Spatial Audio?

The main thing you’ll need to do is to engage the (somewhat hidden) Personalise Spatial Audio ‘training’ that’s built-in at OS level. Atmos will work without completing the training, but for best results, the training will fine-tune the effect to your own head and ear shape to best deliver what your brain has been hearing all these years and max out the effect.

1) Go Settings

2) Select your AirPods (up near the top)

3) Go Personalised Spatial Audio

4) Hit Personalise Spatial Audio

The test is a bit of swine, requiring you to scan your face (fairly easy) and then each ear which is next to impossible as you’re shooting the side of your head and therefore can’t see the instructions on the screen. Try screen mirroring to a device in front of you or hold up a mirror. Or engage a friend to help. Eventually, it will work.

Top tip: Move your head VERY slowly left and right, hold it a good arm's length to get your head and side of face in and shoot from a higher angle looking down slightly.

Note that Head Tracking doesn’t work with AirPods 1st and 2nd generation (but Spatial Audio and Dolby Digital do).

Spatial Audio (with Dolby Atmos) is great… But you’re right. How do I turn off Head Tracking?

No probs. The buttons for turning it off (and toggling between trusty old stereo and the new Dolby Atmos mix) are rather hidden in the latest Apple OS:

1) Enter Control Centre (swipe down from the battery icon top right)

2) Press and hold on the volume slider

3) Press the blue button at the bottom and centre to toggle through the various modes as you listen (including ‘off’ for both Dolby Atmos and Head Tracking)

I’m not sure Dolby Atmos is for me. Who’s it really for?

Sure. Atmos in music is all a bit superfluous with improvements that are – at best – questionable to most and undetectable to others. And pros such as Nigel Godrich and Bob Clearmountain aren’t particularly convinced either.

Where Atmos comes alive is in the creation of new musical experiences where the creator of the music (or soundtrack, or ambient experience) wants the music (or whatever sound they’re working with) to come from behind you or above you. There were experiments with ‘quadraphonic’ recordings – permitting the recreation of true 3D ‘soundscapes’ – in the '70s, but the format never really took off.

Pioneers such as Tom Middleton and companies such as Illustrious (headed up by artist/producer Martin Ware) use Atmos to create swirling soundsculptures for art installations and more. Middleton’s on-going work, beating insomnia by creating the perfect, safe, 3D world in which to drift off, has helped millions to finally get a good night's sleep.

Also, Atmos is fun! A pure novelty. A new way to hear the tracks you love, and if you want the old stereo mix you’ve always listened to, just turn Atmos off. And genres such as jazz – most at home in small, compact clubs where, often, there was no stage and the musicians would jam together in the round – sound great in surround. It can be real ‘close your eyes and you’re there’ stuff.

And modern pop – a genre built on aural trickery and whizz-bang moments – sounds great with producers using the extra power to place percussion and finger snaps precisely in a 3D space or build cathedrals of reverb around soaring vocals only to snap it away and get literally ‘in your face’ moments later.

Are remastered old tunes better in Atmos?

The current spate of tinkering with classic tunes is inevitably where the wheels can rather fall off the spatial bandwagon.

Nobody wants unimpeachable classics needlessly mangled in the name of progress and – thankfully – real spatial disasters are hard to find. However, all too often, while the spatial engineer’s intention was to ‘breathe new life into...’ or ‘give a radical new take on...’ a familiar favourite, it’s a simple fact that true fans of the music (whose ears are fine-tuned after years of repeated listening) are far more likely to perceive all their hard work as ‘why does this sound weird?’

It might be that you’ve never really listened to your favourite Beatles classic or hoary rock standard up close, in which case spatial often delivers a peculiar, pleasant new kick. But if you’ve ever sat between finely tuned speakers or if you have a favourite pair of headphones that you often settle into, then there’s a good chance that you’ll not only be left wondering what all the spatial fuss is about, but also what exactly has gone ‘wrong’.

After all, if the goal of playing back recorded music is always ‘to hear it exactly as the artist intended’ then – by definition – Atmos, Spatial and other surround treatments on new mixes of classic tracks are introducing fakery that they didn’t imagine at the time and – if they were around today – might quite probably outrightly object to.

But let’s remember. As with all art, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. There’s no right. There’s no wrong. There are no rules.

Try spatial. You might like it. Modern hits often sound bigger. Fuller. More powerful.

Just don’t expect the tracks you know, love and live your life with to get ‘better’ than they already are. Different? Sure. But better? We’ll leave that up to you.

10 spatial audio tracks that hit the mark

Elton John and Britney Spears – Hold Me Closer

Spatial really sings with modern, parametrically EQ’d content. When a mix engineer has already carved out a frequency notch and placed a sound in that space then that sound is so much more transportable when working in surround. Sounds can be placed without reintroducing the muddiness that wide stereo mixes often fix. Thus, Hold Me Closer sounds far more enveloping, with great domes of vocal reverb overhead and snappy-fingered bass front and centre.

Cheap Trick – I Want You To Want Me

This cheesy, almost mono, track-that-you-didn’t-know-you-loved-but-you-do finally sparkles in spatial audio. A rushed, cheap, '70s recording is finally given the room it needs to breathe and the latent energy and performance in the track finally shines through.

Fleetwood Mac – Go Your Own Way

Trust sonic snobs Fleetwood Mac to get surround right. While some spatial treatments only elevate specific elements so that they wind up competing for your attention, so the spatial mix of Rhiannon pops an already brilliantly recorded track even further into your consciousness. You could argue that the vocal starts to take a supporting role, but when the playing is this good, you want to hear it.

Harry Styles – Late Night Talking

Flicking Atmos on and off is like toggling the old ‘Loudness’ button on an '80s radio/cassette… But the way the bassline jumps out and Harry’s superstar mix vocals (ie, too loud) settle back into what reveals itself to be a funky track, sounds much more delightful and fun in Atmos than in the stereo mix to our ears.

INXS – Never Tear Us Apart

It’s perhaps with superlatively simple singles like this that spatial has the most power to ‘do its things’. While the synth strings sound brighter and a little bigger, Michael Hutchence’s vocal has never sounded more mesmerising.

Talking Heads – Once In A Lifetime

Is it better? We’re not sure, but by gosh it’s definitely different. Listening to Once In A Lifetime in Atmos or Apple’s Spatial Audio is like pulling a dust sheet off your favourite sculpture and seeing it in a whole new light. You might not like the new cracks and wrinkles but it’s never felt fresher.

Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World

In Atmos, the band finally sounds as full and as glowing as Armstrong’s legendary vocal. Meanwhile Armstrong himself sounds clearer and closer than ever, with the room that surrounds him and his orchestra providing perfectly sympathetic backing where everything is just ‘there’.

Diana Ross – I’m Coming Out

Yes. Bigger. Fuller. But with all the gaps, separation and groove that makes this a classic still totally titanium intact. This is all the tricks done right and a familiar all-analogue favourite just got fresh as a digital daisy.

Tiesto and Charli XCX – Hot In It

Like creating a 3D version of a computer-generated Pixar movie, all the sounds and shapes of Hot In It are entirely digital and thus are easily pluck-outable and positionable wherever its makers like. Thus, popping Hot In It in and out of Dolby Atmos is like throwing all your Lego up in the air before pressing a button to have it magically fly back to form the Batmobile. Very slick and very now.

The Beatles – A Day In The Life

Now here’s a divisive one. Listening to the Atmos take for the first time the track sounds superb. Large, all around you, with multiple layers on John Lennon’s voice stretching off in front and behind you. Pop it back to stereo and the track – perhaps by virtue of familiarity – suddenly sounds sharper and more ‘real’ and ‘there’… But when somebody spoke and I went into a dream… Wow… Some might hate it, but this Atmos mix needs to be heard.

And 3 that don't work

Lizzo – 2 Be Loved

A prime modern example of the spatial hand being too careful on the tiller. In fact, spatial 2 Be Loved sounds positively mono in comparison to its ‘popped out’ smart stereo mix.

When in stereo, percussion is placed hard left and right and minutely offset to play up the funk and give a big splashy soundfield. In spatial the sound is denser… More full and ‘zoomed in’… But that only tapes up the gaps between the distinct tracks in the mix. Nah…

Queen - Bohemian Rhapsody

How crazy could they have gone with this mix? How wide and wonderful could it have been? Full marks for the spread on the intro “Is this the real life?” vocals but, perhaps in recognition of the track’s place in our collective psyche, they chose not to go in too hard with the trickery and as the track kicks through its gears you’re left with a denser wall of sound that – incredibly – actually diminishes the definition between the superlative separate parts of the original.

Wet Leg – Wet Dream

Surround trickery magically sucks the excitement out of Wet Dream. If the original stereo mix was the sound of thrashy band playing their latest out in front of you, then this needless rehash is them sulking backstage afterwards. Stick with the stereo. Or for best results, just play as its makers intended: Too loud. Out of a phone. On the bus.

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.