Classic interview: Stewart Copeland on his Police career, "When I did that hi-hat thing, I wasn’t wondering if I’d get away with it. I was thinking, ‘People love that sh*t! I’m doing it, kiss my ass!’"

The Police legend looks back on every album

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There can be no denying the influence The Police and their drummer, Stewart Copeland, has had on music’s vast and varying landscape.

More than 50 million albums were sold worldwide in an era when sales were physical records, tapes and CDs, amassing 14 UK and 18 US Top 20 singles and eight Grammy nominations with five awards. The Police were pop enough, rock enough and chop-filled enough to please a virtual Venn diagram of music fans.

Each member was known for their individual prowess. Andy Summers commanded his effects-laden chords, while Sting laid a foundation with his solid, yet creative, basslines, all the while singing and writing some of pop’s most memorable hooks.

Article continues belowCopeland was the icing on the cake with his fresh and original approach to the drums. Stewart has long ago moved beyond that era, re-establishing himself as an in-demand television and film scorer. He has also gained respect as an orchestral composer, writing operas and symphonic compositions.

In 2019 - just as The Police were about to release the vinyl boxset, Every Move You Make: The Studio Recordings - we made our way up winding roads into the hills of Brentwood, California to meet with Copeland in ‘The Sacred Grove’, his spacious and fully-equipped home studio.

Were you able to step away from the material as a player and just be a listener?

“I wouldn’t do that as an exercise. I think when it comes to legacy bands, our business is the legacy. We all have different careers (now). It’s a body of work that is what it is and should stay as it is. We came to that realisation doing the reunion tour (2007-8).

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“We’re not here to explore our musicality, or where we can take this. No. We’re here to deliver that experience. When we feel that stadium lighting up to ‘Roxanne’, that works on us too. It’s definitely a two-way street.”

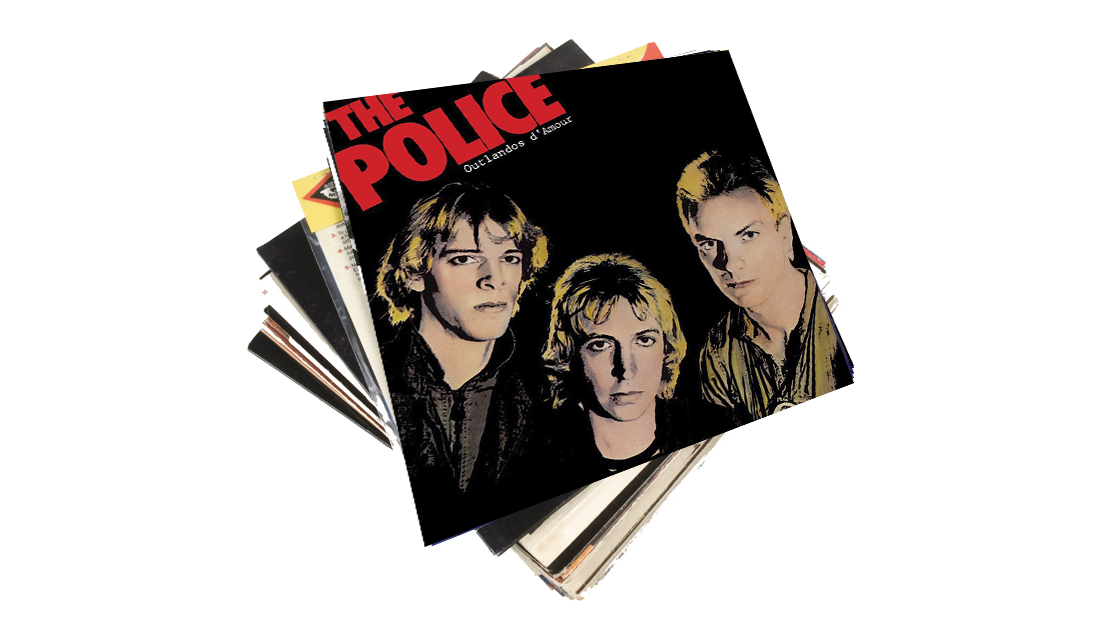

Outlandos D'amour, 1978

The boxset is also a 40th anniversary celebration of the band’s debut record. The album’s oft mispronounced title was conceived by Stewart’s brother, Miles.

Said Copeland: “He thought of the first three album titles. We liked them, so we let him run with that. It was a hybrid language. For albums four and five, Sting had a concept... He asserted his right to name the albums.”

So Lonely: “One of the three songs that established our sound. Although none of those songs are officially reggae rhythms, they are ‘reggae-ish’. They have aspects that make you think about reggae.”

Roxanne: “That was the one that really changed it. I remember it was sort of like a bossa nova (mimics beat while singing lyrics). We agreed we’d have to rock it up. We had to make it harder. And how about this guys? ‘Move the whole beat one beat to the left, like backwards.’ By the way, I will just put this out there again. If your readers want to be on the cover of Rhythm, one beat to the right is still available!”

Can’t Stand Losing You: “That was another of the three rhythm changing tracks that set us on the road that was the band sound. Probably my favourite of all the hits. It evolved onstage into a track that came on the next album, Regatta De Blanc, which is an instrumental.”

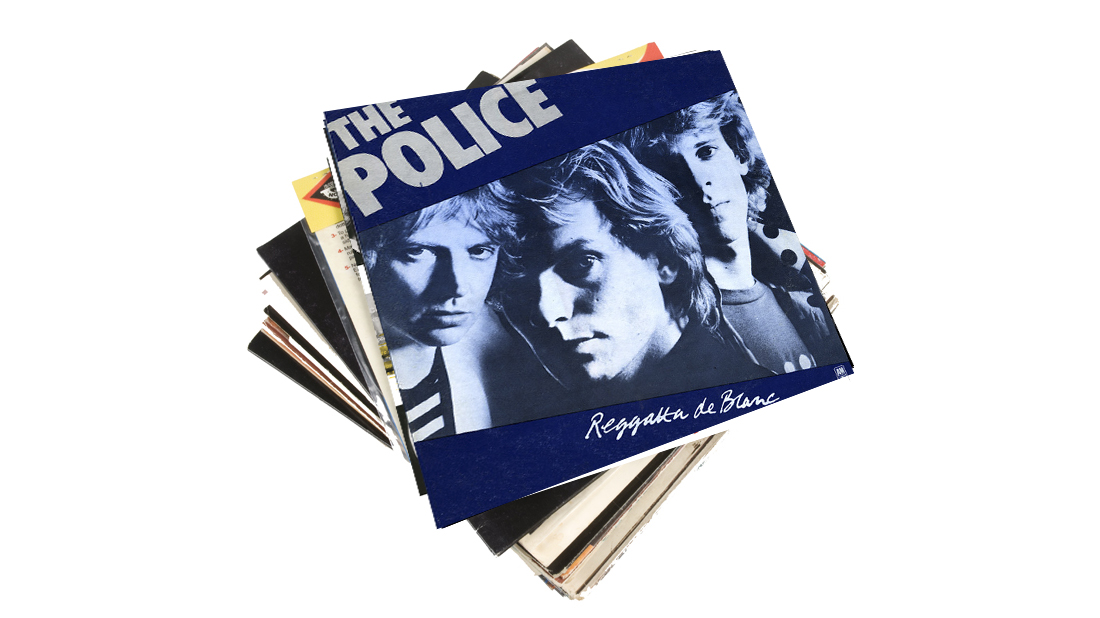

Regatta De Blanc, 1979

With their first album establishing their style, the Police’s second album affirmed their sound.

Copeland’s deft cross-stick stylings and continued flipping of the beat with a pseudo-reggae influence now took on a recognisable sound that would cement him as one of the most distinguishable drummers of the modern era.

What changes did you go through as a player between the first and second albums and how did you develop what became your signature sound?

“The difference was months of touring in America. We had to stretch our material out and we discovered each other. We really found each other. We went in for the second album much more confident in ourselves.

“When I did that hi-hat thing, I wasn’t wondering if I’d get away with it, I was thinking, ‘People love that sh*t! I’m doing it, kiss my ass!’ We got a very strong boost of energy from the American audiences and their response to our music. The band mojo was the highest of our whole career for that second album, which is why it’s my favourite one.”

When I did that hi-hat thing, I wasn’t wondering if I’d get away with it, I was thinking, ‘People love that sh*t! I’m doing it, kiss my ass!’

Message In A Bottle: “This is Sting. Killer song. Opening the album, opening the set, opening everything. One of our best songs, but chart success was not as much as we thought. As the track is fading out I overdubbed the crash accents. God, how I wish I didn’t add those!”

Regatta De Blanc: “That instrumental is where we used to go when we first came to America and had to stretch the set out and improvise. This was one of the improvisations we got into that grew and became the track.”

Walking On The Moon: “That is a beautiful song. Sting says the original lyric was ‘Walking around my room’ (laughs). The whole song fits perfectly. You’re too high after a show, you’re stuck in your hotel room, the world’s revolving and you’re going crazy. There’s nothing in the mini-bar fridge, because the Holiday Inn didn’t have mini-bar fridges. You’re stuck walking around the room.

“By that time I had the Roland Space Echo effects unit. We were into dub, where the reggae guys would do the echo. I discovered all of these rhythms with this echo. I had a footswitch to turn it on and off so I wouldn’t drive everybody nuts. When we recorded this song, I had that delay line going.

“Since then, I’ve heard young drummers and cover bands playing all of it. The echo part and the drum part. I did that live. It’s how I kept the tempo because the echo would keep me honest.

“At the end of ‘Walking On The Moon,’ I remember the engineer’s words, ’Stewart, that’s going to put you on the map.’ I remember thinking, ‘Really?’ Sure enough, that’s the one people bring up as being ‘the’ one.”

Did I ever want to stand out? No, not really. I’m a member of a band, I’ve always felt that way

Did you ever use click tracks with The Police?

“We did some on the reunion tour. I hated it. In the studio, I think we did on ‘Every Breath You Take’ and ‘Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic.’ I overdubbed onto Sting’s demo.”

Did you ever worry about replicating studio overdubs live?

“Never, ever. I hear bands say all the time, ‘How are we going to do this live?’ We never asked that question. There’s only three of us. Andy did a lot of overdubs of all different kinds of sounds. He’s like Fred Astaire with that foot pedal.”

The Bed’s Too Big Without You: “Another great song. Just the idea of the song is so poetic. That’s so true to the way Sting felt about his then wife. And a fun rhythm. Really hard to sing and play bass at the same time. Sting confessed he had to actually practise!”

Contact: “I wrote that one. I like the idea of where the lyric was attempting to go but didn’t quite nail it. The fact that ‘Contact’ made it onto the album is an indication of how short of material we were. Sting was under pressure to write songs and he came up with some of the best songs he ever wrote.”

Did you ever think about the drum part when you wrote lyrics or phrasing?

“No. I do now, writing opera. I understand that even unmusical spoken language has a melody. It’s pitch-less, but there’s still a melody. So, there is that connection. The drum part has received a lot of comment on that track because I was going hell for leather crazy. We played it around and around at the end. We played 50 of them and chose the best ones.”

Were there any songs where you wanted to express yourself more on drums?

“Not really. I loved being part of a team. I never really saw myself wanting to break out of that. I didn’t need to, it’s not a part of my psyche. Did I ever want to stand out? No, not really. I’m a member of a band, I’ve always felt that way.”

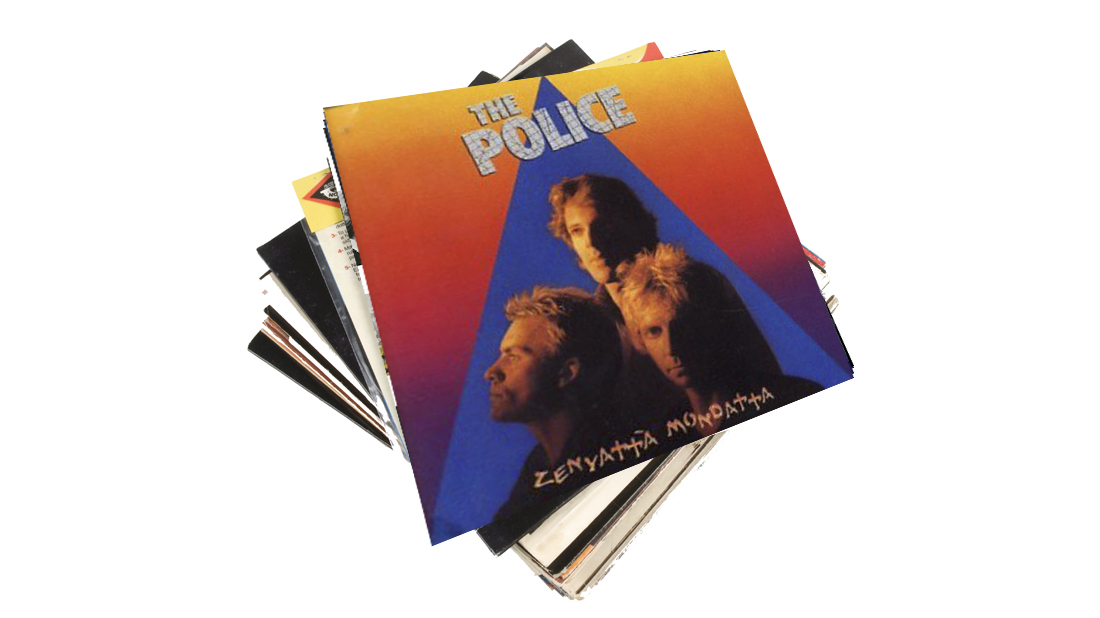

Zenyatta Mondatta, 1980

“Zenyatta was recorded in Holland. The third album, we now know that Sting is writing the hits. The pressure is on him, individually.

"We had the record company executives showing up in the control room, having opinions. We felt invaded in the studio. That’s when the tension in the band started. It was the beginning of the conflict.”

Don’t Stand So Close To Me: “Another of my favourite songs. A really big one. There’s this buzz at the beginning. The record company said, ‘What’s that crackle? People will think it’s a mistake!’ We just thought that had so much atmosphere. We love that sound of the tape being turned on.

“You have your two-inch tape and it runs past the heads and you take it back to the beginning. But the engineer starts at a different place every time. Auto-locate hadn’t been invented yet. We’re doing the guitar overdub so the guitar track is in record mode. When you listen to the track you hear that tape start up. I thought that had a lot of atmosphere.”

Bombs Away: “Another one of my songs. A surprisingly high number of my songs on that third album. It was about a nihilistic view of warfare. The Middle East war was already well in progress. The Six-Day War had happened. The ’55 and ’58 wars. I’d lived in Lebanon during these incursions. But it was so far away. Bombs away in old Bombay. Who gives a rat’s ass? Sh*t’s going on on the other side of the world while we live our lives.”

I swear the guitar riff in the beginning is out of tune. Andy says it was the flanger.

De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da: “A capricious moment, I think, by our lead singer, to f*ck with American radio DJs. It sounds really dumb, but it is one of his most poignant and observant lyrics. It drives me nuts and Andy and I have argued about this, but I swear the guitar riff in the beginning is out of tune. Andy says it was the flanger.”

Behind My Camel: “That’s an Andy song, an instrumental. We won a Grammy for that. I think that’s Andy on bass. It was Andy’s day to do that song and Sting hid the two-inch tape. He should have known Andy better than that! We stopped everything until that tape was found!”

Shadows In The Rain: “Another of my favourite obscures. If we had gone down that direction, we would never have been a huge band. I’m surprised it made it to the album. It’s one of Sting’s songs. It’s all atmosphere and coolness. It really gave Andy a showcase where he would create this wash of orchestral sound.”

Ghost in the Machine, 1981

Spirits In The Material World: “I see on YouTube where people are analysing the drum fill as the most f*cked up intro ever. I didn’t see it that way. I never played the ‘1’. Reggae is all about leaving out the ‘1’.

"That song really maxes out that principal. It’s a bit sterile, that performance of it. I didn’t really understand the rhythm but I played what I could figure out that day. I’d just heard that song five minutes previously.”

Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic: That had a very different story from all the others. Sting had spent some time in Montreal at Le Studio. Rush country. There’s a French Canadian pianist, Jean Roussel, a very enthusiastic and gifted musician and they did some songs. This was one of them.

"That’s the other of two (songs) where somebody else plays on a Police album. We tried everything. We deviated from the demo to the extent it’s not a hit anymore.

“I had an epiphany overnight. I come in to the studio and said, ‘F*ck it, just put on your demo and show me the changes and count me through!’

"One take, one morning, and that was it. That’s the drum track. Sting was standing over me, grumpily conducting me through it, which is how I made all the changes. Quite a complex song with a lot of different pieces. I was angry at the time, which is where a lot of the energy of the performance comes from.”

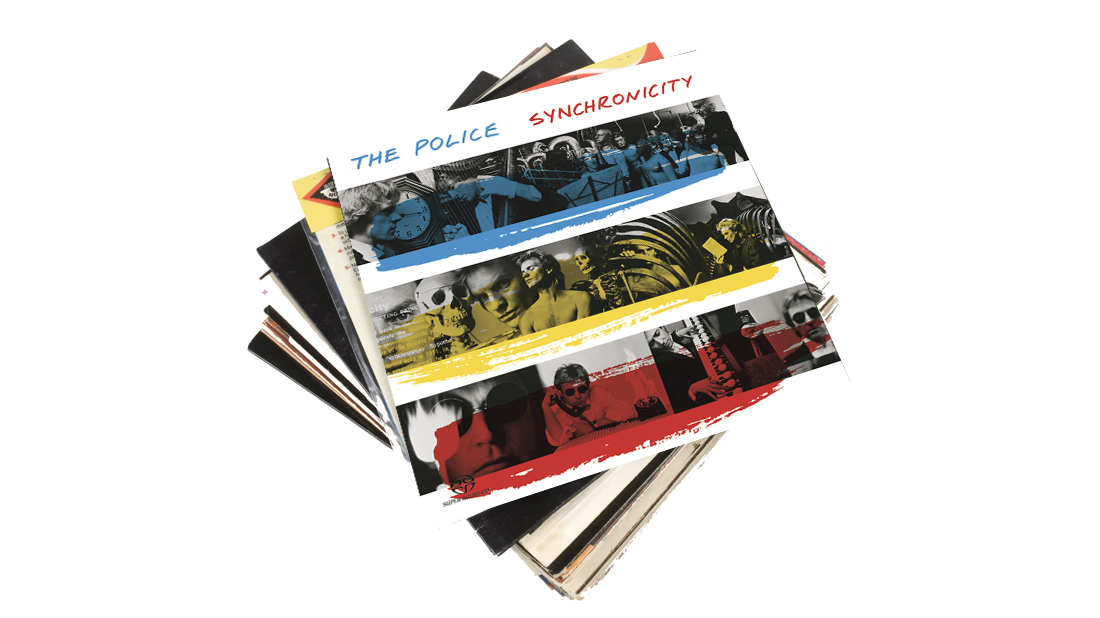

Synchronicity, 1983

“A very conceptual album lyrically.

"Sting wouldn’t explain his lyrics, he would just sing them. Sitting next to him doing interviews, they’d ask him: ‘What’s that song about?’ We’d hear him and say, ‘Really?’ A classic example is ‘Every Breath You Take.’ It’s a sick, twisted song. I thought it was a love song. Just like all those people that get married to it not realising it’s a dark, demented track.”

Every Breath You Take: That guitar riff was Andy’s. That track was our biggest hit. That started out as a Hammond organ piece but Andy went off and figured out those chords, fingering and that harmony. That’s all Andy. The drum part was composed rather than played. That was done with a click and we had a big battle about it. By that time, Sting had bonded with the Oberheim hi-hat sound, which did have a hypnotic quality. I insisted on playing the hi-hat myself.

“We went back and forth finishing that song and we fought like cat and dog over the f**king hi-hat. I doubt if anyone can tell from listening to the record. But the drum part was composed. It was all overdubs. The snare was a snare and a gong drum. The hi-hat was eighth notes. The kick was separate. All separate takes. It was an outlier. Certain tracks are outliers in that is not how we normally did things. The drums, I’m proud of how simple they are. They’re very Zen.”

We fought like cat and dog over the f**king hi-hat.

King Of Pain: “Great lyric. Magical lyric. I enjoyed playing a xylophone melody in the middle of that. I can’t think of much else to say about it. ‘There’s a little black spot on the sun today.’ I have no idea what that means but it breaks my heart.”

Wrapped Around Your Finger: “I thought that lyrically, this track really took itself too seriously. The teacher and the student becoming the master. It was all a little bit artsy. It would have made a great Rush track! (laughs) I say that with love in my heart for Rush and Sting!”

Tea In The Sahara: “Fantastic. We’d stretch that out live and Sting would pull out his oboe. On that one, an orchestra is coming out of Andy Summers. He is more influential than many guitar ‘heroes.’ His sound, his concept, was unique. On solos, he can burn it up, but his contribution was that harmony, combined with the sound textures, it was a unique soundscape.”

The Police’s drummer confesses his admiration for the poet he played percussion for: “I’ve discovered a trait of great poets. I only know a few, Sting being one of them. At the dinner table, you can flatten him with an argument.

"He can’t defend his position. He knows what he feels and you’re not going to dissuade him. You can technically win the argument but he’ll go back to his hotel room and land on three words that destroy all argument, all logic.

“We had arguments about the Cold War, which was going on at the time. The best example is, he came up with the line, ‘But the Russians love their children too’.

"My father, being a CIA man, gave me a perspective that was different than Sting’s point of view. Any argument I had about the evil empire, about the Soviet Union competing for mineral resources... destroyed. You can’t argue with a poet.”

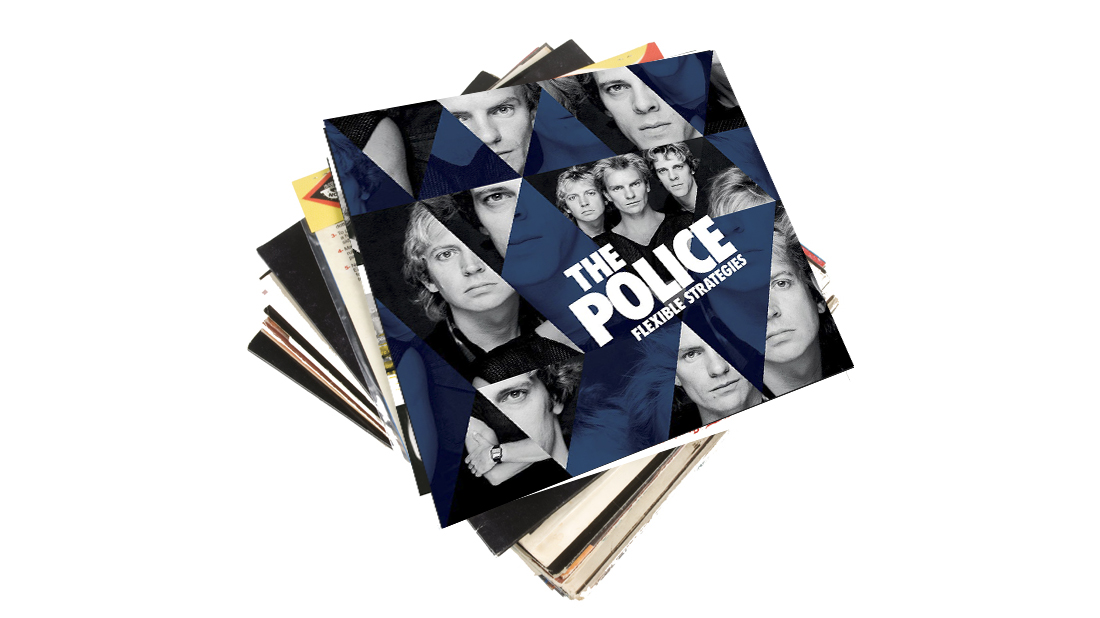

Flexible Strategies, 2018

How did you decide what material went on the bonus album?

“Things are proposed and we all agree. We all enjoyed interacting on the subject. Andy and I are getting a lot of attention on this particular disc because these were all the B-sides, which is where our, um, inferior material ended up (smiling). Now we have a place on this album dedicated to the other tracks of The Police.”

Dead End Job: “I wrote the bassline. It pushed the parameters because in punk in 1977, you were not allowed to play chops. Chops were frowned upon and that’s a chop!”

Landlord: “Another of my basslines. I only knew three chords so I was all about the basslines. My brother, Ian, who was an agent, wrote some of those early lyrics. I didn’t think in terms of words in those days. I’d never listen to the lyric. I don’t know the words to a single Beatles song, but I could sing you every drum fill.”

In punk in 1977, you were not allowed to play chops. Chops were frowned upon

Visions of the Night: “This was one of Sting’s songs that he brought from his previous band. The lyric was really un-punk but we let him off that time. This one we got away with because it’s poetic and not part of the time. Of course, now we realise the value of it. We were out of the straitjacket of that punk fashion.”

Lowlife: “One of my favourite songs. That’s another example of a song that didn’t make the album, was used as a B-side, 40 years later it’s one of my favourites.

It features a saxophone solo. One of only two tracks that features somebody other than the three of us.”

Murder By Numbers: “One of the things I like about ‘Murder By Numbers’ is the story of its recording. It is worth considering that from Zenyatta... on, the drum part was conceived 20 minutes before the recording. There’s a handful of tracks otherwise, but mostly I never heard the song until that morning. Twenty minutes or an hour later and you’ve done three takes and that’s what’s down on granite for the rest of my life.

“On further reflection, it worked. Maybe that’s where some spark came from that seems to have inexplicably inspired so many. ‘Murder By Numbers’ was the extreme case. We’re at dinner. Andy’s plunking his jazz chords, as he does, and Sting says, ‘Hey, I like those chords.’ He pulls out the lyric, ‘Murder By Numbers’. So, they work it out while we’re having dessert. Well, let’s record it! I walk over to the drums and they go downstairs into the recording building.

“By the time they get down there, I’m already playing. Hugh Padgham (producer), hits the red button, they kick in and that’s the track.”

Did you always record with the three of you playing live?

“Always. We’d put the track down, the three of us, and then they’d replace all of their parts. When we did the three of us together, we were not in the same room. We were at the same time, but not in the same room. I was in the dining room, Andy was in the big room, Sting was in the control room. Even for a track like that, a total jam, we’re connected by earphones.”

It used to be called ‘Truth Kills Everybody’. I said, ‘Dude, that’s just wrong! That’s philosophically wrong!’

Truth Hits Everybody (Remix) : “It used to be called ‘Truth Kills Everybody’. I said, ‘Dude, that’s just wrong! That’s philosophically wrong!’ We argued about it. Unbelievably, in the early days, he would take advice. When he wrote 15 hits in a row, he took less advice (laughs)! Truth doesn’t kill, it nourishes. Truth arrives at everybody. It still phonetically works and is a better thing to say. A rare victory (laughs)! Some of the victories I regret and some of the losses, I cherish.”

Getting Slightly Deranged

Copeland describes how he applied his film scoring and arranging skills to score his film, Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out.

“After The Police, I woke up decades later and realised I had all this Super 8 footage. You can’t cut it because there’s no negative. Then, they invented computers, so I’m chopping it up on the computer now. Next thing you know, I’m at Sundance (Film Festival) with a feature film.

“What made it interesting was that it’s not a documentary about a band like MTV, it’s from inside the band. Making the film, I cut up all of The Police tracks. I’ve got Pro Tools of all The Police albums multi-tracked. I call them ‘Derangements’. I took all the multi-tracks and created entirely new tracks. I took the backing tracks and got the chorus swirling around. It’s all modular and interchangeable.”