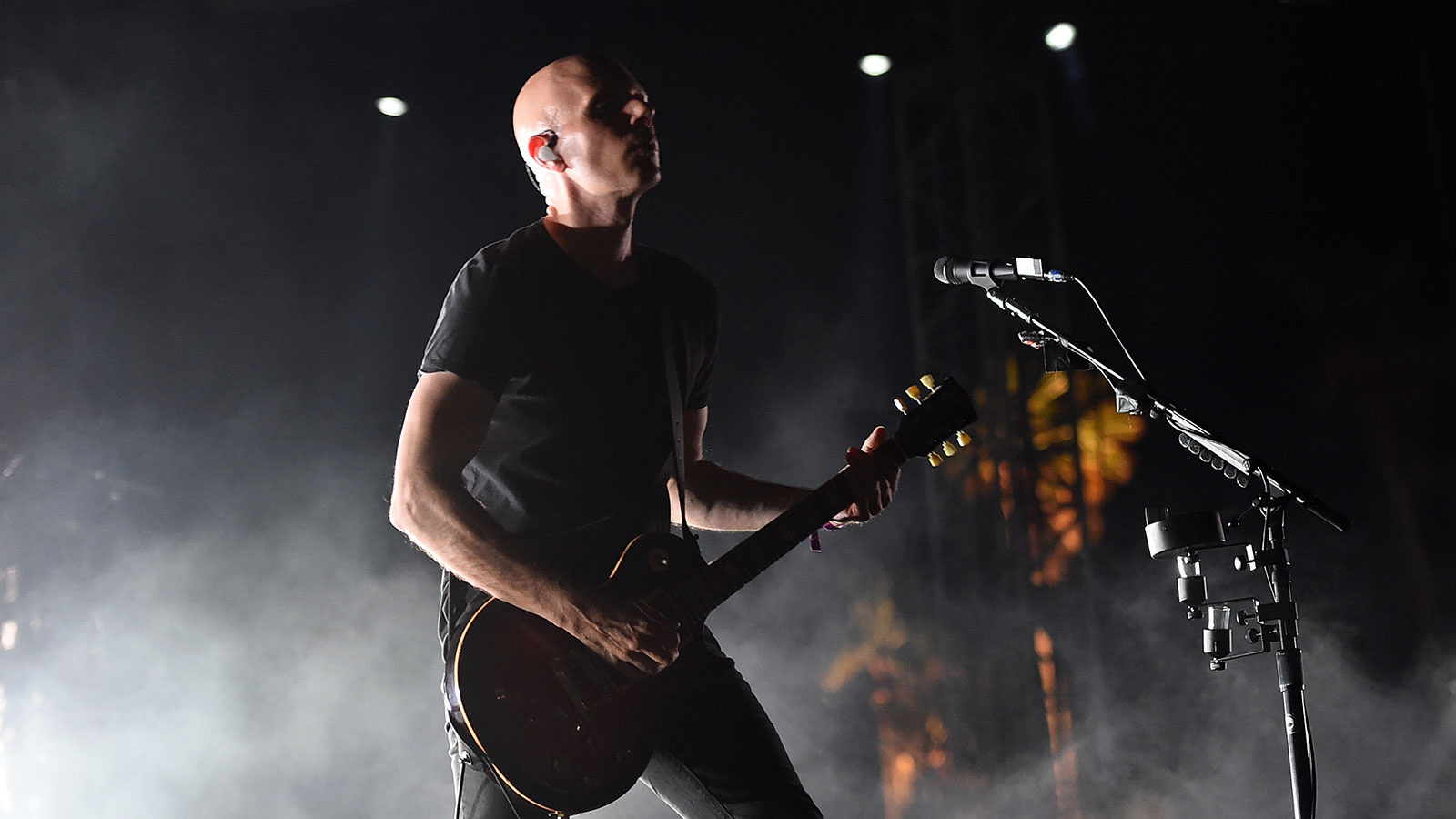

A Perfect Circle's Billy Howerdel: “What I lack in technical ability, I try to make up for with soundscapes”

The player, producer and founder on his alternative approach to guitar tones

As A Perfect Circle return with their first album in 14 years, we meet their founder to talk balancing his player and producer mindset, and the different perspectives that make him one of contemporary alternative rock’s most original players.

Everyone has their own idea of a guitar hero, and some of the most inspiring players in rock have been those who combine their role with a bigger picture. Alternative icons who emerged in the 80s like Johnny Marr, Robert Smith and Will Sergeant were thinking beyond just their guitar. And they were then able to carve new and inspiring paths for rock music as a result.

Billy Howerdel is certainly part of that lineage, and when he and Tool vocalist Maynard James Keenan formed A Perfect Circle in 2000 with their debut album Mer de Noms, he affirmed himself as not just a modern rock player with his own distinct voice on the instrument, but one with a talent for framing that in ear-pleasing production and fresh arrangement.

That’s still very much in evidence on the band’s long- awaited return with Eat The Elephant, but things have changed too...

This is the first album with an outside producer being involved alongside you. Why did you decide to bring Dave Sardy into the process?

Everyone starts with blues and I wasn’t very rebellious but rebellion to me was liking non-guitar music

“I scored my first feature film almost two years ago [D-love] and for two or three days I hired an assistant who could just run the computer and be able to say, ‘Start recording, stop recording, give me another take, double that.’ I’d never sat on the couch and just played. I’ve always had the computer by me, set up a mic and just done that. I really liked the result, it was interesting so I thought I’d give it a try [again]. To be able to see what the songs were like from above and not be as caught up with the screen.”

You spend a lot time crafting tones and it shows on this record - do sounds tend to inspire songs?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Big time. Well, this record was written mostly on keyboard. So in the past the sound has inspired more than even on this record. This record was written left and right hand that was also a little by intention.

“If someone asked me to play one of our songs at a campfire [before] it would be hard to figure out. Because it was always written as ‘the bass guitar has this role, then this guitar and this guitar are flavours that weave in’. Whereas now I could play The Contrarian or Eat The Elephant or Disillusioned and certainly ...Fish, I could play them - badly - but I could play them as one part.

“So I guess maybe the songs have a different feel because of that. As eclectic as I think this record is there’s an anchor and that’s having more of a traditional song structure to it in that way.”

Something that stands out in your work is how much space you leave for the other instruments - where did that mindset come from?

“I attribute it all to the fact that I didn’t want to play blues guitar. Everyone starts with blues and I wasn’t very rebellious but rebellion to me was liking non-guitar music. I was a big Elvis Costello fan and Squeeze but I liked The Cure and Echo And The Bunnymen... things like that, and they weren’t guitar hero bands - and Missing Persons in particular.

“The guitar parts were just one colour amongst many but didn’t stand on their own - it was hard to play one of those songs on the guitar without it just being an acoustic version.

“I had this CD car Walkman and when I pulled the little 8" cord halfway out, it went out of phase. I could hear whatever was just out of phase, so no kick drum, no bass guitar and no vocal. So anything that was spread all the way left and right is all I could hear. In the 80s things were panned hard right. So I got to figure out all those varied layers that no one could hear except for the artist. I got really into that.

“Now it made sense when I was figuring the song out and it was much more interesting than, ‘Here’s a rock riff with a big guitar chord.’ Those are easy and are fun but it was those little colours that came out of uncovering the secrets of what people were playing in the background for ambience.”

Racking up

You use Axe-Fx live, but do you use it for effects in the studio?

“No, very little. I’m able to find interesting sounds with it but a lot of times I don’t use it in the recording process. Sometimes, I’ll take a sound I’ve already used, like for live on The Noose, which wasn’t [the sound] on the record, but the sound I used live for The Noose was inspiring for The Contrarian. So I’ve already done the work and I know how to play that sound. I know how to play the pedalboard. So there were a couple of colours like that but for the most part I play somewhat dry and then add it later.

“There were a lot more effects baked in this time and that was more from Dave. He likes to record with a DI and two or three amps and then mix them later. I’ve never done that. I get the one sound I know it’s going to be and any experimentation I’m going to do next is with effects or filters of some kind. Generally, I know what that part wants to be. So that was different on this record.”

I hate red-hot guitar. I don’t know if that’s a term but it’s saturated I guess. Where things fold on themselves and the detail is gone

What’s that like when you’re tracking?

“Well, I find the amp I want to listen to the most; what’s the most reactive. But usually I’m in a room with the amp. It’s rare that I’m in the control room playing. I like to have the pickup in front of the speaker but [with Dave Sardy] I’m not controlling these files and seeing what they all are. A lot of these songs had so many tracks. I couldn’t make head nor tail of it so I’d listen back and say, ‘That one’s bothering me or that’s cool.’”

Do you tend to use pedals or plugins?

“A lot of built-in effects on the amps. Sometimes a reverb on the amp, a spring reverb. My friend Oliver Leiber has a studio where we went to track quite a bit for the guitars and he’s just got a playground of vintage museum quality pieces over there. There were some really interesting sounds that I got over at his place playing with old little combos and things like that.”

So it’s quite an old-school approach. You’re not in the digital world of guitar when recording as much as some people might presume?

“Not at all. Yes, there are plugins you put on if you want a delay and there’s some reverbs that were baked in.”

Your overdrive sound has a lot of presence and weight but it’s not oversaturated, did you use your 1978 Marshall JMP Superlead 100 with the modified preamp a lot for recording too?

“A lot. I’m a big midrange fan, I have a lot of it. My presence knob is so touchy that it’s hard to mark, even when you do, you have to sometimes go in and tweak. That’s where all the feedback and all the overtones happen. So, with my settings, my bass is full, my mid is full, my treble is at seven and the presence is at nine on my amp and it’s big but it’s very fast... I don’t know how else to say it but the sound is very reactive and fast.

“I hate red-hot guitar. I don’t know if that’s a term but it’s saturated I guess. Where things fold on themselves and the detail is gone. If I’m going to do that it’s an effect. I like that if I’m playing on the neck pickup and I roll down I can play completely clean, and it’s hard to do that when you’re fuzzy. Because, no matter what, it still sounds fuzzy and buzzy. Like a tube is about to go out when you’re playing with a modern metal sound. It’s just my preference.”

On the spot

With sustain and drone parts, is that you finding a sweet spot in a room in front of an amp?

“Yes, big time. And it can be turning the tiniest bit, or that window over there is giving too much slap, put some foam over that. We tracked a lot of this in real studios, such as Sunset Studios. And that’s another thing, I’ve never really tracked guitars in a studio before. Tracking in a bigger room was new to me. I’ve usually tracked in much smaller spaces, so this time there were room sounds. It was really tracked in a traditional way.”

When you play live do you also have to think very carefully about your position with cabs and volume?

I have to get back to the spot I have marked on the floor for certain things, where I go to for certain parts

“Yes, where I stand. Sometimes I have two 4x12s but the last year I’ve only played through one. A Marshall 4x12 and the amp I’ve always played - well, the two different amps I switch between. Mostly a JMP and the Friedman. Getting interaction with the amp is important to me. But it depends on the song.

“If it’s just barre chords, maybe not so much but even barre chords, the way it swells back and forth, it has to be at a certain volume, unfortunately. And that’s hard when you’re playing in a smaller place. It’s hard in a big arena too because there’s a lot of distance. I have to get back to the spot I have marked on the floor for certain things, where I go to for certain parts. Or I just know now for the relative position.

“The good thing about arenas is our stage setup is the same every day with pillars and lighting. Everything is exactly the same so when you play you know your marks to hit.”

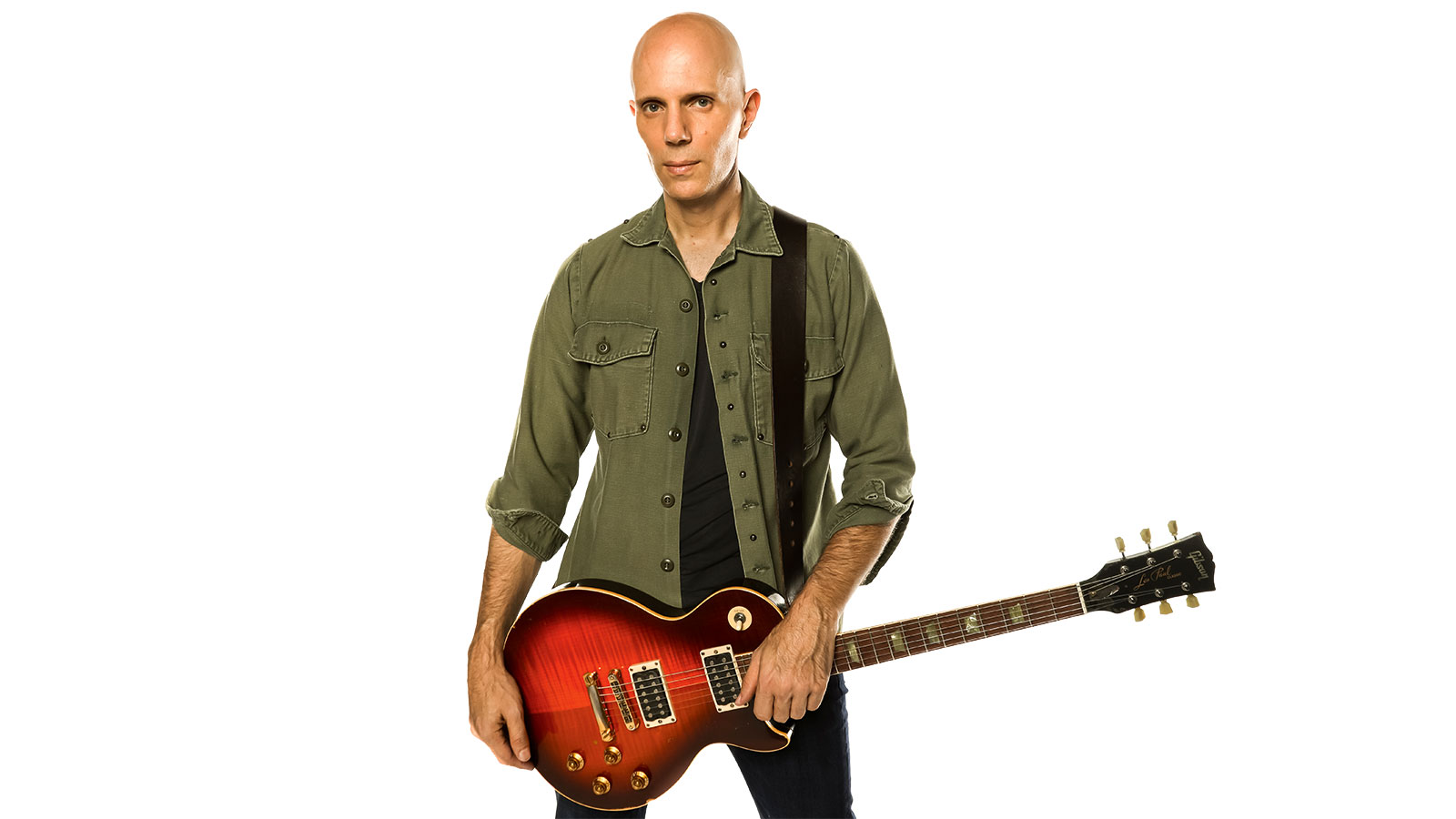

Are you exclusively using Les Pauls on the studio as well as the stage?

“For the most part. In the studio I’ve got a couple of other colours here and there. There was about the same amount of blend on this record. I’ve got a Gibson 175 with stock pickups. My [LP] guitars have Tom Anderson pickups so they’re very different to a Les Paul.

“The pickups sound harsh the way I have them. I have an H3+ in the bridge [H1 in the neck] and they’re very unforgiving. I pick up a regular guitar in normal tuning and other pickups and sometimes I’ll think, ‘Why don’t I play this?!’ Because it just sounds so forgiving and nice. But there’s a little extra work I need to do to get this to sound good and maybe that’s part of the character of the sound of the band and my playing. What I lack in technical ability, I try to make up for with soundscapes, and that’s part of it.”

One thing that’s easy to overlook is the transitions between your guitar parts seem very carefully orchestrated with things like delay trails. Is that quite challenging?

“Yes because you might get the performance right but the transition is off. That’s a lot of programming the Axe-Fx. I’ve got a tech, Steve, who works for me. He’s musical, he’s in a band and he knows the Axe-Fx and how to get good sounds. Typically, I wouldn’t be here right now. I’d be home doing that for two months and he’s chewing on it right now. Get me close and then I’ll come in and tweak with you. But that’s what’s great about the Axe-Fx: I can get almost anything out of it.”

Do you have any advice for players who want to combine the roles of composer, producer and guitarist?

“Everyone has access to what I didn’t have access to back then. It’s about trying to not be paralysed by choices. And trying to sound like something you love. I think a melting-pot approach is better than a singular.

“For me, it was wanting to be Will Sergeant and Robert Smith and Randy Rhoads and Warren Cuccurullo from Missing Persons. I couldn’t master any one of them but I could come up with my own sound from the soup that was created from all of them.”

Pretty great machine

Billy tells the story of his #1 Les Paul, via Trent Reznor and an eye-watering credit card bill

“It’s a 1960 Classic Reissue but I think it was manufactured in ’91. When I was working as a guitar tech for Trent Reznor he broke many guitars and that was the very first guitar I was given [to work on]. It just arrived in the box on the day I arrived in Georgia. We were doing production rehearsals in Atlanta and I’d just got the gig.

“I was removing the pickups and the soldering iron slipped out of my hand and burned a tiny little spot. And I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m fired and we haven’t even done a show.’ But the tech next to me reassured me. I didn’t know anything about Nine Inch Nails.

I didn’t realise how destructive it was… I think Nine Inch Nails went through one to seven guitars every night on that tour

“I’d heard Head Like A Hole once or twice in a goth club and that’s it. So I didn’t know anything about the show, I didn’t realise how destructive it was. And the first night I think he threw it up and it hit the lighting troughs and broke the neck off it. So I thought, ‘Okay that’s that.’ But that was par for the course. I think they went through one to seven guitars every night on that tour.

It’s a side story but that’s why I had such good credit. I was 24 at the time and I asked the production manager, ‘Can I put these on my credit card and you pay me back.’ So he said, ‘Okay, and I ended up putting I think $200,000 on my credit card and I paid it off immediately. So, I had totally amazing credit - when I went to buy my first house the guy said, ‘You have like Ronald Regan credit!’

“So that guitar in particular was the first one and as the headstock had broken off I found another guitar just like that. We went through so many that had the exact same [break]. I found another one with the same coloured headstock, put it on. Poorly. It’s at the wrong angle because it’s not the same headstock, it’s more flat. I just tried to remove enough wood to get the splinters to go together and epoxy that. So it’s a Frankenstein guitar but for whatever reason it’s not about that why I love it.

“It really is the best sounding guitar I’ve ever had. It’s not forgiving but it’s the most interesting and it plays great and I have to get it refretted, which scares me, because I know it’s going to change it. But that’s always been my number one.”

Rob is the Reviews Editor for GuitarWorld.com and MusicRadar guitars, so spends most of his waking hours (and beyond) thinking about and trying the latest gear while making sure our reviews team is giving you thorough and honest tests of it. He's worked for guitar mags and sites as a writer and editor for nearly 20 years but still winces at the thought of restringing anything with a Floyd Rose.