6 "wrong" production techniques that turned out right

We round up six examples of how ignoring conventional studio wisdom can lead to fantastic musical results

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sometimes music production can be too clean and perfect: colouring within the lines doesn't always yield the best results.

Here are six examples of techniques where taking the extreme, dirty or just plain wrong approach turned out to be... well, right.

1. Misuse of the TB-303

The Roland TB-303 could be the most famous misused instrument. Originally designed as a bass guitar accompaniment, the 1981 synth was disappointingly not particularly good for its intended purpose, so most of the 10,000 units ended up selling cheaply.

We just started twisting knobs and playing, got caught up in these new sounds and forgot about trying to produce a bassline

One was picked up by Phuture, a trio of producers in Chicago comprising Earl ‘Spanky’ Smith Jr., DJ Pierre, and Herbert ‘Herb’ Jackson. “We were all about basslines,” said DJ Pierre. “Spanky was looking around second-hand stores and said ‘I’ve got the 303 but I don’t know how to work it, it’s making these crazy sounds!’ We just started twisting knobs and playing, got caught up in these new sounds and forgot about trying to produce a bassline. It sounded good and that’s really how it happened.”

The ‘it’ was the start of acid house. Their debut record Acid Tracks lit up Chicago and the sound spread around the world. The original 303 rocketed in value but you can emulate a 303 sound – up to a point – with any analogue VA softsynth. See our tutorial for more.

2. The Akai S950 test tone

Not so much a mistake, more a ‘best use of resources at hand’, the Akai sampler test tone was adopted by early jungle producers in the ’90s as the prime source for their half time basslines to hold up those much faster breaks.

4 retro plugins that'll give you that old-school sampler sound in your DAW

There are arguments over which was the best sampler to get the best tone from, or even whether an 808 kick could do the trick (as it did in hip-hop sub bass), but the general consensus is that it’s the pure sine wave that counts and that there was something about the S950’s 12-bit architecture and DACs that made it an especially great candidate.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Either way if you want to recreate it, it’s all about a sine wave, pitching it down an octave or two, its envelope (intricate positioning of the attack and release) and compression. There are also plenty of sites where you can download the S950 test tone as a sample. You won’t get the hardware character but it’s a good foundation.

3. Flanging

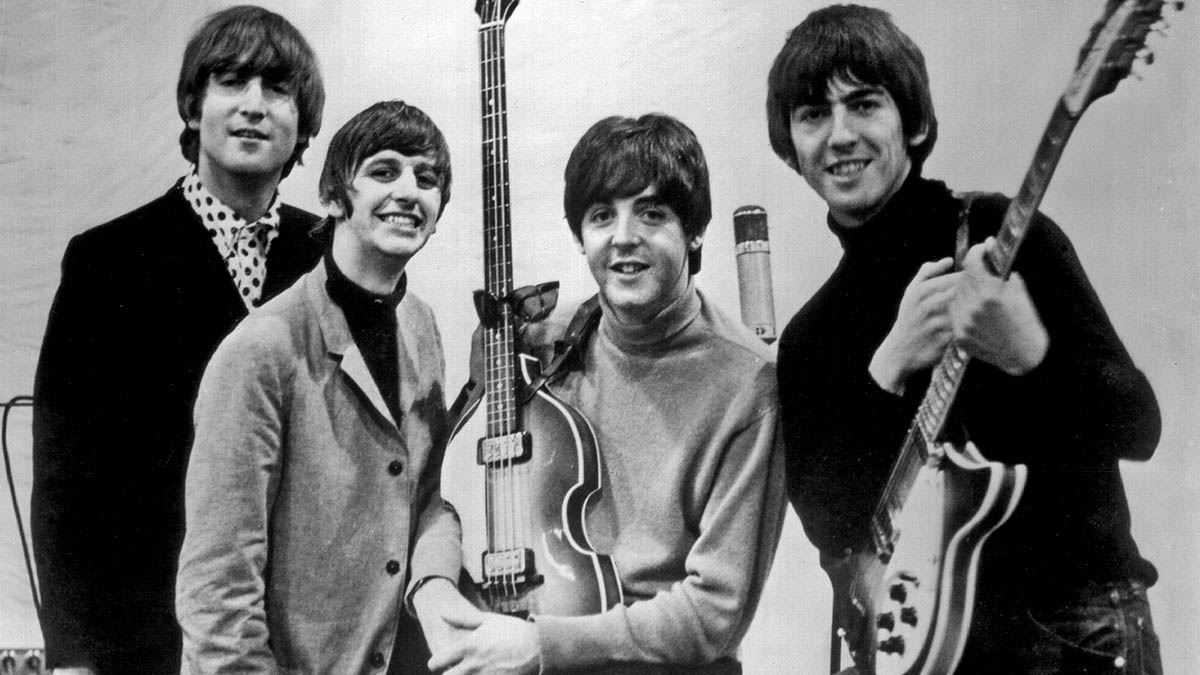

This sweeping frequency effect is thought to have been invented by The Beatles and George Martin during the recording of the album Revolver. Engineer Ken Townsend was experimenting with Artificial Double Tracking of the vocals to avoid recording John Lennon singing twice, which Lennon hated doing. Ken set up two tape recorders and delayed one, resulting in a phasing sound.

Who really discovered flanging, The Beatles, Les Paul, or Larry Levine?

Lennon loved it so much that producer George Martin explained (knowing he could say anything and Lennon wouldn’t understand): “we take the original image and split it through a double vibrocated sploshing flange with double negative feedback”. Which would be a brilliant story to introduce flanging, if it hadn’t already been invented by Les Paul at least a decade earlier, who was experimenting with acetates and the first multitrack recordings and came up with a basic phasing effect.

However, the real flanging inventor – or at least the man who put the sound in pop – was writer and producer Wayne Shanklin. Together with engineers Larry Levine and Stan Ross, he was recording the 1959 hit The Big Hurt by Miss Tony Fisher, and trying to make the vocal louder by playing two versions together. The result of the two tapes playing slightly out of time was flanging, and the resulting hit was the first to bring flanging to the world – and it’s now a plugin in your DAW.

4. Overtuning and the Auto-Tune effect

Like the 303 sound that came from abusing hardware, the Auto-Tune effect came from using Antares software at its extremes. Auto-Tune was developed by Andy Hildebrand who had previously used his signal-processing know-how to examine seismic readings for oil exploration. When his wife suggested he develop software to help her tune her voice, what resulted changed music for the next four decades.

Rick Beato thinks Auto-Tune has 'destroyed popular music'. Here's why he's wrong

Auto-Tune was developed as a natural tuning app, but came with a ‘turn it up to 11’ setting. “I almost didn’t put that in the software,” Hildebrand told Vice, “but I was told, ‘It won’t hurt.’” It was first employed to maximum effect by producer Mark Taylor on Cher’s Believe in 1997. He was nervous about playing the track to Cher but she loved it, and he decided to keep the Auto-Tune use a secret, stating it was a Digitech Talker.

Since then, the likes of T-Pain, Black Eyed Peas and Drake have used Auto-Tune, as has just about everybody else, to the point where some say it’s now too prevalent.

Hildebrand agrees: “It’s a bit overused. People say, ‘oh, that’s Auto-Tune.’ What they don’t realise is that it’s in many songs where you don’t hear it, the way it was intended. I just build the car, I don’t drive it down the wrong side of the road.”

5. Undertuning

Quite the opposite end of Auto-Tune is ‘the mistake’ of an analogue synth falling out of tune and not being locked back in. As with other production effects – see our lo-fi entry – synths that drifted out of tune were once derided but are now embraced, to the point where you get ‘vintage’ controls built into newer synths, which either bring a random feel to certain parameters or simply allow them to drift.

Detuning is most widely used in synths to thicken up and create massive unison-style pads, where one lead sound sits in tune and several sit around it, a few cents out. Lovely. But if you’re Boards Of Canada or any other techno distorters, any synth drifting away from the norm is a beautiful thing.

It’s an easy one to do in your DAW, too. Either grab that Vintage knob or pitch rotary and twist and record. Better still, but slightly more complex, gently modulate your pitch with a slow-running LFO.

6. Forget hi-fi

We don’t want things in tune and nor, as it turns out, do we want them sounding clean. The use of lo-fi sounds, tape hiss and wobble have become fashionable thanks to ‘the Pro Tools effect’ where everything was starting to sound just a little bit too good.

Now, vintage gear emulations include all of the inherent and unpredictable circuit issues of the original hardware to make our productions that bit more interesting and, at their extremes, that extra bit more dirty.

Whether it’s that tape hiss, vinyl noise, analogue saturation or full-on distortion, there is a plugin for that. You thought that the days of hiss between tracks were gone. Now we want them back. What next? Mono?

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.