5 songs guitar players need to hear by… Death

How Chuck Schuldiner breathed life into death metal and took it from primal gore riffs to a new sense of enlightenment

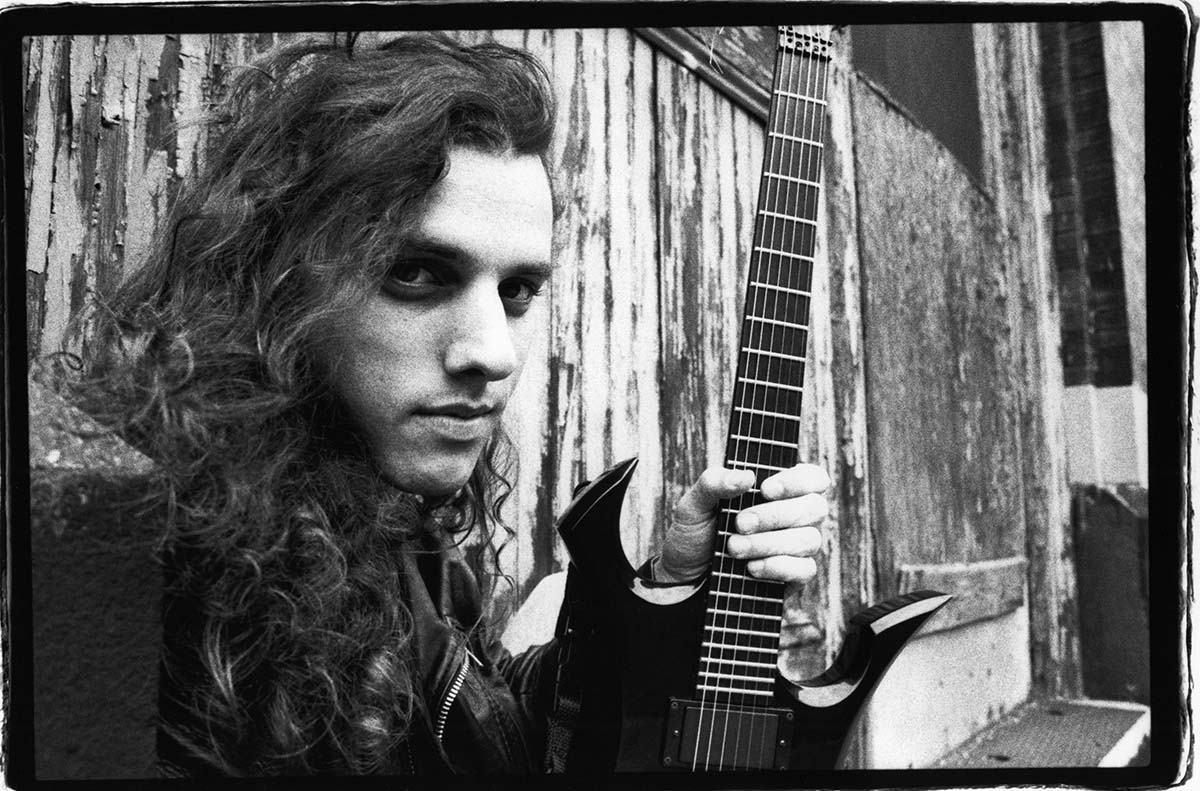

Death metal has had no shortage of trailblazers but none did more for its evolutionary development than Chuck Schuldiner of Death. His restless creativity enacted various stages of radical Darwinism upon death metal’s form, taking the genre from the raw-meat gore of the late ‘80s towards more progressive compositions and a spiritually enlightenment that broadened its subject matter.

Schuldiner’s vision proved death metal could grow its brain and process high-minded concepts without taking all the danger out of the sound. Death metal will always have graphic violence, Lovecraftian cosmic horror and a morbid fascination with the postmortem, but Schuldiner proved it could tackle philosophical issues, too. The direction of travel was already clear across Death’s first three albums – Scream Bloody Gore, Leprosy, and Spiritual Healing

Recorded in Los Angeles with Autopsy’s Chris Reifert on drums, Schuldiner on vocals, guitar and bass, 1987’s Scream Bloody Gore is one of death metal’s foundational texts, packed with riffs and enough songwriting nous to put together a timeless track such as Zombie Ritual, which remained in the Death setlist until nigh-on their last show on 13 December 1998.

But a process of refinement was already under way, with Schuldiner decamping to Morrisound Studios in Tampa, Florida, for Leprosy (1988). The raw savagery that animated Scream Bloody Gore remained in full effect but Leprosy was altogether more three-dimensional.

For the recording, Schuldiner enlisted his old bandmates from their pre-Death days as Mantis, with Rick Rozz offering a capable foil on lead guitar and Bill Andrews on drums. Terry Butler was credited on bass but Schuldiner once again handled the low end. Butler would join Death on tour and track Leprosy’s successor, Spiritual Healing.

Human was the great evolutionary leap, a clear break from the past, yet with Schuldiner’s presence, it was still unmistakably Death

This onwards march of musical progressivism left many casualties. As the sound evolved, so too did the lineup. James Murphy replaced Rozz for Spiritual healing. Those who got onboard with the visceral B-movie content of Scream Bloody Gore would recognise much of that primitive sound in Spiritual Healing, but the arrangements were growing more ambitious, the playing got better, and the subject matter – the power of belief, the predatory cynicism of televangelism, genetics – grounded Death’s sound in the everyday.

By Schuldiner’s interpretation, death metal needn’t draw from the world of fictional horrors when there were plenty out there in the real world to explore. This new vision, allied to a growing confidence in his arrangements, led to the recording of the band’s most influential and best-selling album, Human.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The creative destruction of the Death lineup was one of Schuldiner’s greatest gifts. For Human, Cynic’s Paul Masvidal and the late Sean Reinart joined on lead guitar and drums respectively, with the prodigiously talented Steve DiGiorgio bringing a fusion feel on bass.

His vocals, pitched in a scream just north of a death growl, ensured continuity, but so too his melodic sensibility, which drew inspiration from NWOBHM’s more baroque practitioners

Human was the great evolutionary leap, a clear break from the past, yet with Schuldiner’s presence, it was still unmistakably Death. His vocals, pitched in a scream just north of a death growl, ensured continuity, but so too his melodic sensibility, which drew inspiration from NWOBHM’s more baroque practitioners and transplanted them into the rough-and-tumble context of death metal.

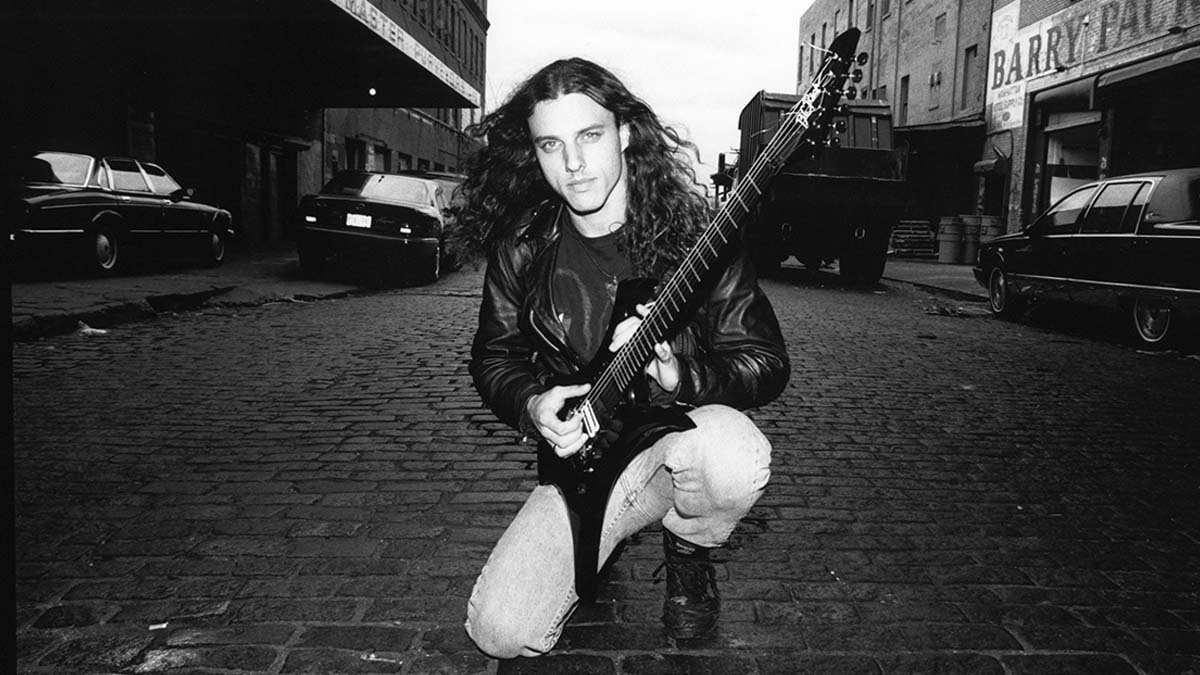

All this was done with a simple setup, too. Schuldiner was no gear head. He kept a functional lineup of single-pickup BC Rich Stealth models, the most famous of which was finished in black. All had a fixed bridge and a high-output DiMarzio X2N humbucker in the bridge position.

He used few effects except for a Boss distortion on Scream Bloody Gore. He favoured solid-state amplifiers. Like Dimebag Darrell and George Lynch, he used a 120-watt Randall RG100ES head, later gravitating towards Marshall Valvestate heads.

During the tour for Human he used a mic’d up Gallien-Krueger 250ML. A stereo lunchbox amp and a favourite of the likes of Alex Lifeson, Gary Moore, David Gilmour and Iron Maiden, the 250ML is something of a cult classic, and is equipped with a powerful four-band EQ section and onboard gain, compression, stereo echo and stereo chorus effects. A second-hand unit in good condition will set you back £500 or less.

After Human, Schuldiner’s writing got more audacious, and we will look at some of those examples here. In picking five tracks of special relevance to guitar players, it is tempting to front-load them with latter-day picks, where the arrangements stretch out and Schuldiner is joined by the likes of Andy LaRocque, Bobby Koelble and Shannon Hamm, whose playing fleshed out latter releases with flashes of virtuosity.

Is virtuosity Death’s legacy? The discography is rich in performances of technical excellence, and any band to host Gene Hoglan on a drum stool is well-positioned to deliver virtuosity. But there are others in death metal who took the idea of virtuosity further, arguably to the genre’s detriment as technical proficiency take that crucial human element away.

No, Death’s legacy, which is to say Chuck Schuldiner’s legacy, is more than that. Perhaps it exists in those ideas that twisted death metal into new shapes, and in how the force of personality and performance can ensure that death metal needn’t have a bloodless future just because it is looking beyond gore for inspiration.

1. Left To Die (Leprosy, 1988)

Left To Die leaves everything on the slab. You have the melodic canvas extended by NWOBHM, a double-time opening riff that takes a nosedive into the undiluted mosh-fuel of the first verse riff, the morbid inertia from Scream Bloody Gore affording Schuldiner a second pass at perfecting the necro anthem, and holding all this together is his unerring gift for songwriting.

Even this early in his, Schuldiner was a provocateur, upending the songwriting rule book, eschewing repetition, operating like the editor of an action movie in cutting together contrasting riffs and ideas with brutal efficiency. Structurally, Left To Die is audacious. Ninety seconds in and there have been more ideas than some bands manage over the course of an entire album.

Of course, you could ask why Pull The Plug isn’t here – a death metal contemporary of Metallica’s One, expounding on the hopelessness felt by those on life support. But then you could make the case for Born Dead, the title track, Open Casket, etc… Scream Bloody Gore established the death metal alphabet, its periodic table, but Leprosy helped put all this together.

Like all great heavy metal records, Leprosy is a world-building album, helped in no small part by Ed Repka’s career-best cover art, and an unfussy, raw and organic sound engineered by Scott Burns, who would soon likewise establish himself in death metal history and help place Tampa, Florida, at the centre of its universe.

2. Flattening Of Emotions (Human, 1991)

In just four years Schuldiner had fully augmented Death’s sound. It was akin to taking one of Argento’s undead, fitting him in a suit, and teaching him the French horn. But while this might seem like a quantum leap from Leprosy and Spiritual healing, Death’s signature elements remain intact and close to the surface. Once more, just as Left To Die references 80s NWOBHM so does Flattening Of Emotions, with a melodic motif that references Iron Maiden’s Phantom Of The Opera.

Everything here, however, is more complex. That helter-skelter songwriting remains, with Schuldiner often applying the handbrake mid-jam to pivot to a more brutal section, or to let his new lineup stretch their wings. For a taste of the former, check out the tempo change 1min 20sec in. Again, there’s no reason death metal need lose its teeth to accommodate more grandiose musical ideas. Death proved that, with the right touch, melody need not be kryptonite to the art form.

This new approach was perfect for Paul Masvidal’s paradigm-shifting lead playing. One of progressive death metal’s most visionary players, he presented some impeccably executed shred meditations over a rhythmically complex yet still pleasingly hostile arrangement.

Masvidal’s solo on Flattening Of Emotions is more jazz-fusion than death metal, more McLaughlin/Holdsworth than King/Hanneman, and that style wouldn’t work on, say, Autopsy’s Mental Funeral or Cannibal Corpse’s Butchered At Birth – both also released in ‘91 – but on Human, that was just what was needed. That was the enlightenment that Schuldiner had been seeking all this time.

3. The Philosopher (Individual Thought Patterns, 1993)

Individual Thought Patterns deepened the relationship between the primal weight and muscle of death metal’s form, quicksilver rhythms and melodies that stayed in the foreground.

This is one of latter-Death’s more accessible songs, and yet it is deceptively tricksy, opening with a progression of tapped arpeggios over power chords in 4/4 before shifting into what feels like a 9/4 measure of monochromatic chug that’s holding back the pulse of the first beat of the bar as a means of commanding your attention to the vocals. It’s almost like speaking without punctuation, and it’s all to make sure the point gets across.

Shifting time signatures would be a trademark of Death’s later work. It helped recontextualise some of the sounds we had grown used to hearing, offering a fresh perspective. Sure, the sound was familiar, but Schuldiner kept you guessing where that beat might land. This had a huge influence across death metal, where shifting away from a four-to-the-floor arrangement can help sell the unease.

Occasionally, the time signature dictates the rest of the composition, right down to the lyrics. Check out Cannibal Corpse’s Five Nails To The Neck, from 2006’s Kill. Written by bassist/vocalist Alex Webster in 5/4, the time signature inspired the lyrics.

4. Crystal Mountain (Symbolic, 1995)

With a title that sounds inspired by Manilla Road, Crystal Mountain exists in perfect tension between the two worlds of Death. You have the uptempo syncopated chug of the opening riff, one foot in the savagery that defines the genre, then you have these great moments of caprice, puncturing the aggression with a sense of wonder with an emaciated arpeggio at the chorus, the bass and vocal holding the melody.

The only album to feature Bobby Koelble on guitars, Symbolic leans heavily on Schuldiner’s melodic sensibility, eschewing some of the jazz-fusion chutzpah of Human for passages those informed by classic steel of Euro metal bands such as Sortilège and H-Bomb. He even found time to integrate an acoustic solo as the song fades out.

This was Gene Hoglan’s final recording with Death, and his drumming is a lesson for all guitarists; when putting together a band, get the best drummer you can find. Here, the then former, now current Dark Angel sticksman takes the rhythmically complexity and makes it flow, which is just as well because there’s no point in having all these shifting time signatures if they are going to pull you out of the song’s magic.

Sometimes an album will be described as progressive and means very little. There’s little point in being musically progressive if all the ideas are dull. But there was a point to Schuldiner’s more ambitious arrangements, the same venom that sauced the early recordings was refracted in his more iconoclastic approach to mood and melody.

Again, this is death metal as world building, and Schuldiner’s writing caught the imagination of bands such as Meshuggah, Gojira and Baroness, and also served as a warning to others in the scene. Kelly Schaefer of Atheist has spoken before of Schuldiner’s competitiveness and how it inspired them to take more creative risks, to put their own spin on death metal.

5. Flesh And The Power It Holds (The Sound Of Perseverance, 1998)

The epic Flesh And The Power It Holds is a dizzying tour de force of modern death metal that does all but escape the genre’s centre of gravity. The Sound Of Perseverance found Schuldiner in a transitional period once more. He had Shannon Hamm as his foil on guitar, Richard Christy on drums, and Scott Clendenin on bass, and a bunch of ideas originally for his Control Denied project that eventually got repurposed for the final Death album.

Flesh And The Power opens conventionally, with a melody presaging lightning kinetic riffs ahead, and throughout Schuldiner pitches his vocals high on top, but it soon ventures into death metal surrealism, with a fusion middle section, ablaze with Schuldiner’s outré lead phrasing, bringing us to what feels like a false ending before it hurtles towards a full-speed verse and the song’s denouement.

In the context of the Death discography, Flesh And The Power It Holds is not just the maturation of Evil Chuck’s vision circa ’88 but of all the ideas he gathered on the way. The direction of travel was his design, the evolutionary pace was at his command, but this transformative sound also rested on the contributions of his collaborators through the years.

There’s maybe something of the Masvidal influence in that middle section, albeit with a very different technique and feel; it’s the intent to spin death metal on its axis, expose it to elements hazardous to its being in order to make it stronger, to future-proof the art for generations of death metal bands to come. And come they did.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.