"There’s nothing fair about stealing an artist’s life’s work”: The worrying rise of AI music extenders

Many AI-driven platforms now offer the means to extend your tracks to any length you want, but how legal is its underlying algorithmic training?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

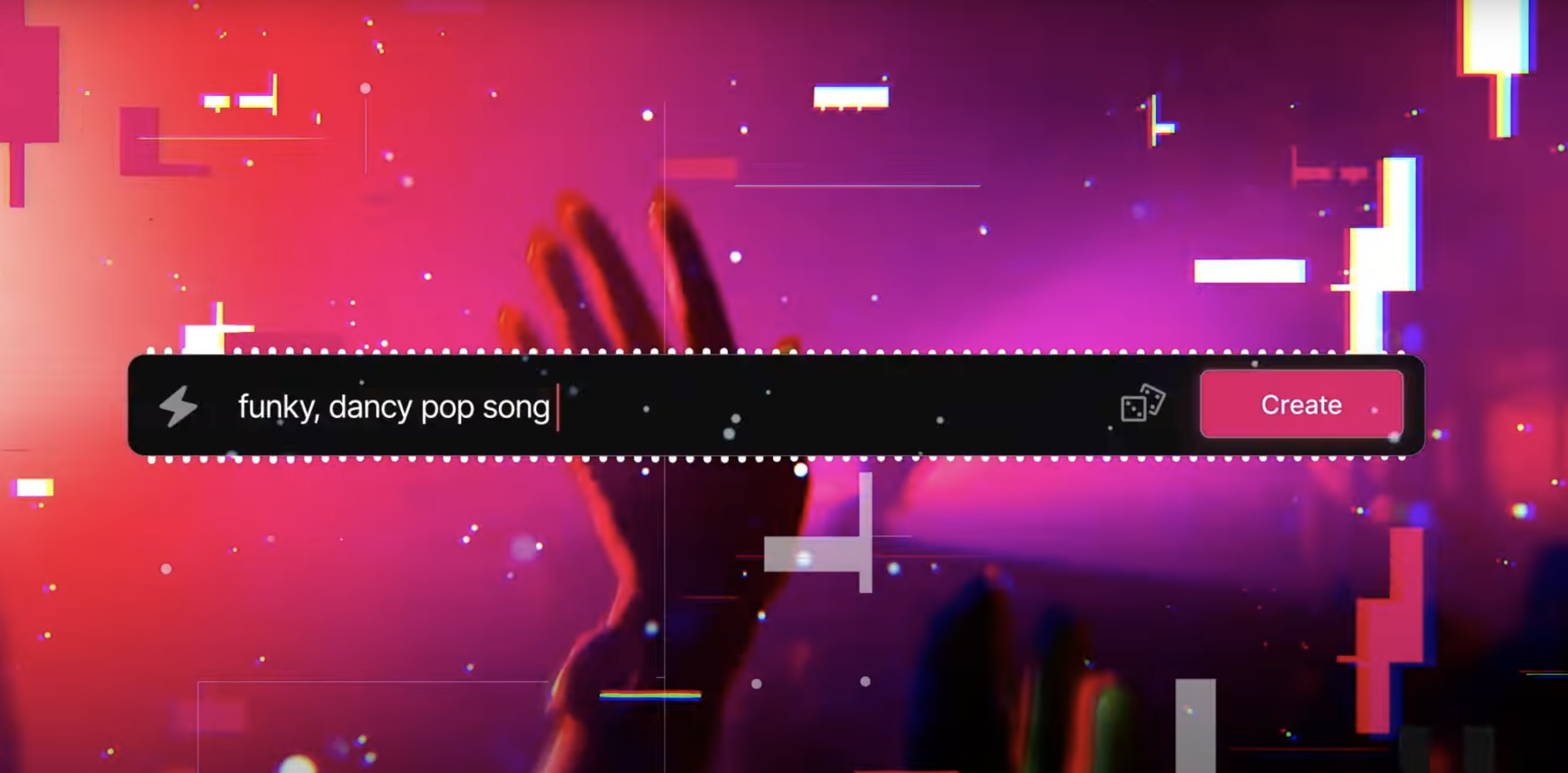

Earlier this year, we ran a story on the updates of Udio and Suno – generative AI tools trained on colossal archives of existing music, and, therefore, primed and ready to immediately concoct fully-fledged and arranged tracks in response to user prompts.

Our initial take was one of skepticism, with its text-generated results resulting in – as our writer Matt Mullen opined – “Largely bland, uninspiring tracks that you could imagine soundtracking a joyless insurance commercial.”

But it was the other addition, that of taking the fragments of audio ideas from music-makers, and building out full tracks from the most rudimental of starting points, that excited us the most.

While certainly useful for those at a creative crossroads, the implications of using an audio extender of this type were worrisome.

Was that finished, AI-augmented track really YOURS? Or is it a collaboration between yourself and an AI (and an AI that’s been trained on archives of music by other artists, we might add).

Major labels certainly seemed to share our unease, and wasted no time with asserting their view – legally. In June, The Recording Industry of America (RIAA) filed lawsuits against both Udio and Suno, alleging ‘"wilful copyright infringement on an almost unimaginable scale”.

Suno cited 'fair use' in its response; “[Our] training data includes essentially all music files of reasonable quality that are accessible on the open Internet, abiding by paywalls, password protections, and the like, combined with similarly available text descriptions.”

The RIAA was swift in their retort, stating that “Their industrial scale infringement does not qualify as ‘fair use’. There’s nothing fair about stealing an artist’s life’s work, extracting its core value, and repackaging it to compete directly with the originals.”

While the Udio and Suno case is ongoing, and fairly unique, many other platforms are offering the track extension service. Alternative platforms are the aptly-named ExtendMusic, the popular platform AIVA (which dubs itself a ‘personal AI music generation assistant’) and SoundVerse.AI – which proudly extolls the virtues of “breaking free from fixed audio lengths” and “Provides a dynamic canvas for creative exploration. Opening endless possibilities.” All very noble and empowering for struggling artists, right?

The real talking point here isn’t so much the creative potential it could trigger for music-makers but more ‘how’ the new material has been generated.

While we’re not suggesting these platforms’ algorithms have been trained on copyrighted material, Many of these platforms are trained on vast archives of recorded music – i.e. other artists’ work.

Is there just the slightest risk of music-makers, assuming that their new track – bolstered and fattened out by an AI audio extender – is entirely their own work. When in actual fact, it’s harnessing the hard work of myriad creatives, and baking that work into your track.

Understandably, lively forum chatter has been sparked by this topic, with various debates circling the notion that as long as the platforms are mining third-party libraries and adding the results to your ideas, the end results cannot be called your own, and that this latest innovation is merely a fad, and part of the AI investment boom that has been taking place over the last five years.

Others indicate that these types of platforms are highly useful for road-testing ideas, vocal-lines and alternative bridges/sections for tracks.

While many musicians will have qualms about the ethics of these types of platforms, there's nothing stopping the widespread distribution of AI-generated or infused music.

In a joint press release in June, Spotify’s Daniel Ek and Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg spoke of the promise of open source AI… “and its ability to drive progress and create economic opportunity globally”.

While Ek emphasised Spotify’s use of AI in curation and discovery, it’s understandably concerning in the wake of a recent X post where he made the controversial claim that "The cost of creating content is close to zero”.

Are we on the cusp of a music listening ecosystem that supports – and indeed prioritises – AI-driven content, and could well-meaning artists be unwittingly absorbed into this state of affairs by working with AI audio extenders?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.