8 essential melody and harmony tips and tricks to try

Practical tactics for handling the musical building blocks of a track

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What makes a great tune? What is it about melodies that lodge in our heads, so that we sing along to our favourite tracks (but not others we know just as well but don’t like as much) or find ourselves able to listen over and over again, without those tracks becoming dull or repetitive?

The short answer is that there’s no easy answer. If there were, every composer and songwriter would simply tap into a database of great melodic ideas every time a new theme was needed and life would be a whole lot more straightforward. But, as with all things to do with music production, spending some time considering melody and – by extension – harmony and rhythm, can pay huge dividends.

By understanding the musical building blocks of a track, you can make more informed choices about why a melody is likely to be memorable or to lodge in a listener’s mind, or why it might be less memorable and less impactful as a result.

Here we have a few tips to see how we can get better at writing tunes that last.

1. The fundamentals

To understand melody and harmony, you have to know what those terms mean. Let’s start with melody, the easy one. If people ever refer to the ‘tune’ of a track, they mean the melody.

Harmony is a bit more complicated to understand but, fundamentally, it’s the notes which support a melody and make musical sense of it. Let’s suppose you have a melody which moves up in steps from C to D to E to F.

The first note, C, ‘belongs’ to a number of chords, including C major, A minor, A flat major and F major, which means that playing any of those chords under your ‘C’ melody note will sound ‘natural’.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

There’s no need to study or follow a musical rulebook

This is where things start getting complicated. Do you have to use one of those four chords under your ‘C’ melody note? No, you can use anything you like, of course, but some chords will sound more natural and immediate than others, as the ‘links’ between those four chords and ‘C’ as melody notes are strong. But if you choose one of those chords and then move up to your next melody note – D – you’ll probably want to move your harmony too, to a chord to which ‘D’ is a strong relation.

You can use your ears to make these decisions for you; there’s no need to study or follow a musical rulebook.

2. Chord inversions

The notes of C major are C, E and G and most often, you’ll hear a ‘C’ in the bass of this chord. This is ‘root position’, as C is the root of C major. But you could use an E or a G as the supporting bass note and the effect of these is less ‘rooted’ and fixed. Inverted chords are great for the job of giving the impression of a less ‘finished’ chord; quite a powerful musical device.

3. Bone-up on your theory

What are you afraid of? Hard work?

Whilst the tips offered here encourage you to use your ears to choose which notes you pick for your melodies and harmonies, studying music theory will dramatically help your understanding of how music’s DNA works. If you’re rolling your eyes, ask yourself why.

What are you afraid of? Hard work? Well that hasn’t stopped you watching videos about music production and staying up all night working on your mixes. A sense that ‘formal’ training will kill the ‘vibe’ of your approach? Actually, a larger musical understanding will help the creative process, as your musical choices will be more original.

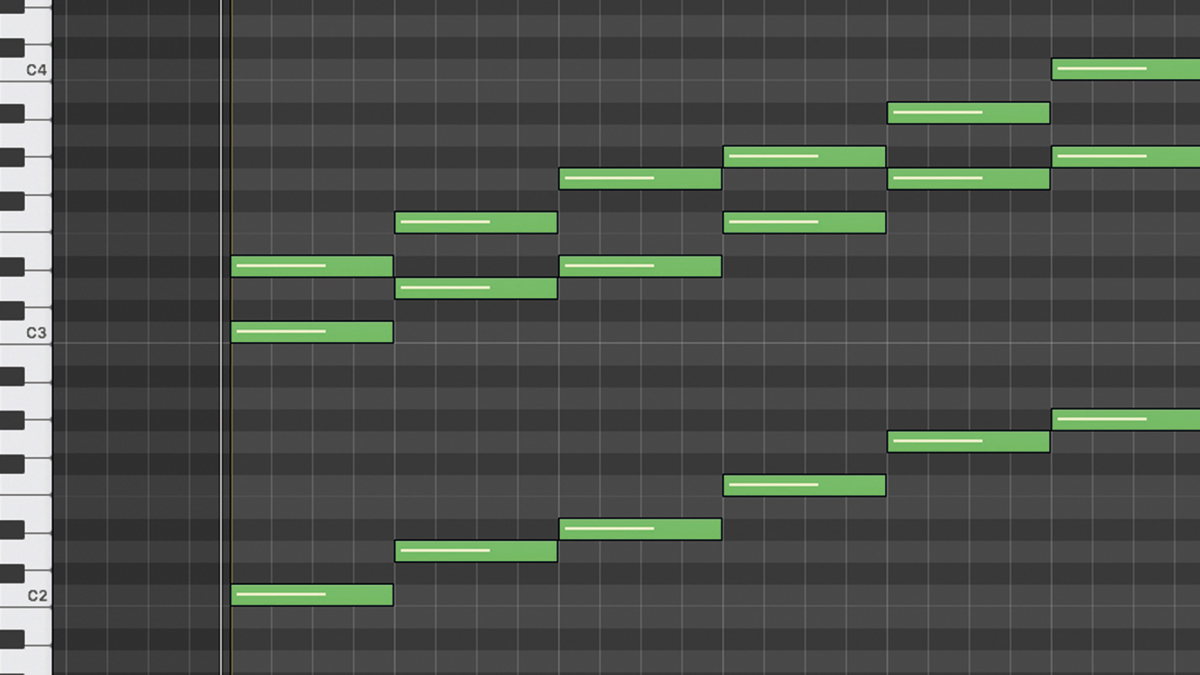

4. Contrary motion

If you’re thinking your way through a melodic and harmonic combination and you’re struggling a little, often the best combinations of these two elements work in contrary motion. In other words, as your melody rises up, try to make the bass note of the chord progression you’re accompanying it with fall. Equally, when your melody line falls, bring the bass notes (and their chords) upwards.

The listener likes to hear one part as a melody and the other part as harmony

This doesn’t have to be true for every single melody note and every single chord but, as a rule, separating the movement between these two parts and imagining a mirror between them – so that movement in one direction prompts movement the other way in the other part – often works well.

The reason for this is that the listener likes to hear one part as a melody and the other part as harmony, so that a single line can be identified as carrying ‘the tune’. Somehow, this is often easier for the brain if the supporting line is as different as possible from the part playing the melody.

5. Hold the bass

Don’t feel the need to change the bass note every time you change a chord. Sometimes holding the bass as what’s called a ‘pedal’ can be really effective, as it builds up suspense through a chord progression.

6. Choose your instruments wisely

Think carefully about the relationship between the melody notes you write and the instruments playing them back. If you’re writing a film score for orchestra, it’s not uncommon for a melody line to play back across several orchestral sections, with the ‘qualities’ of those instruments allowing the melody to be contextualised for different scenes.

Compare a melody played back for a whole violin section (strident, soaring) being played instead on the harp (magical, fragile) or the oboe (introspective, melancholy). Partner your melodies to appropriate sounds and they’ll be more memorable.

7. Build anticipation

Delay reaching the ‘root chord’ of your track for as long as possible. It’s tempting to start your chorus or drop on the root chord; but postponing this can often build up a sense of anticipation.

8. Breaking the rules of harmony

For every key you can write in, there is an ‘expected’ group of chords which sound ‘right’. Sometimes, breaking this expectation provides a more memorable melody.

In the first step of the following walkthrough below, we’ve explored the scale of C minor and drawn up all of the associated harmonic chords with each of its root notes.

If you use any of the bass notes and write a melody which uses any of that note’s associated harmonic accompaniment, you’ll write a melody that makes ‘perfect musical sense’. But it may not be the world’s most interesting tune.

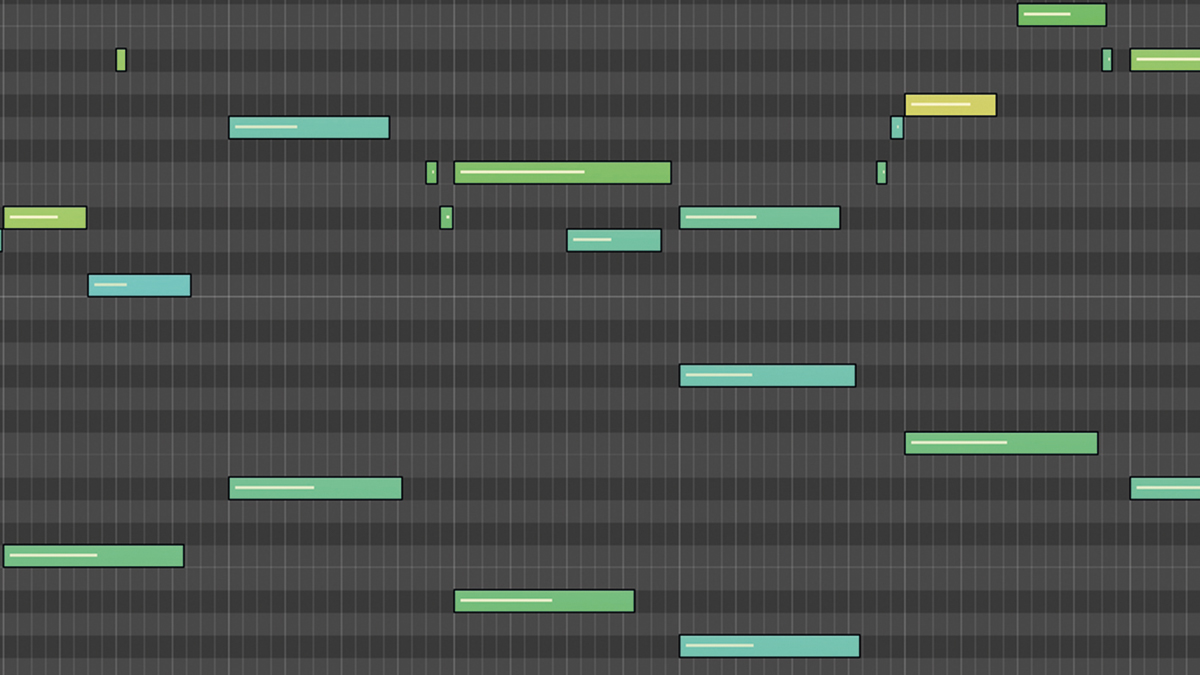

By the third clip, we’ve boldly made the fourth chord not an F minor (as per Step 1) but an F major instead, shifting the accompanying note to A.

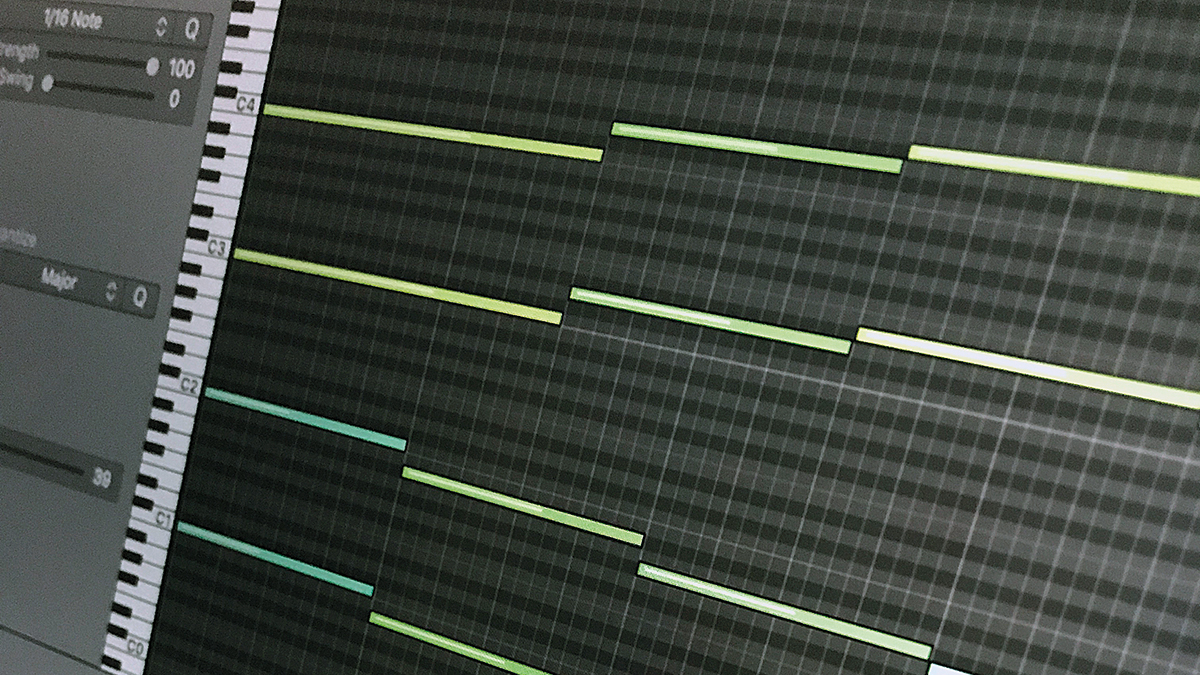

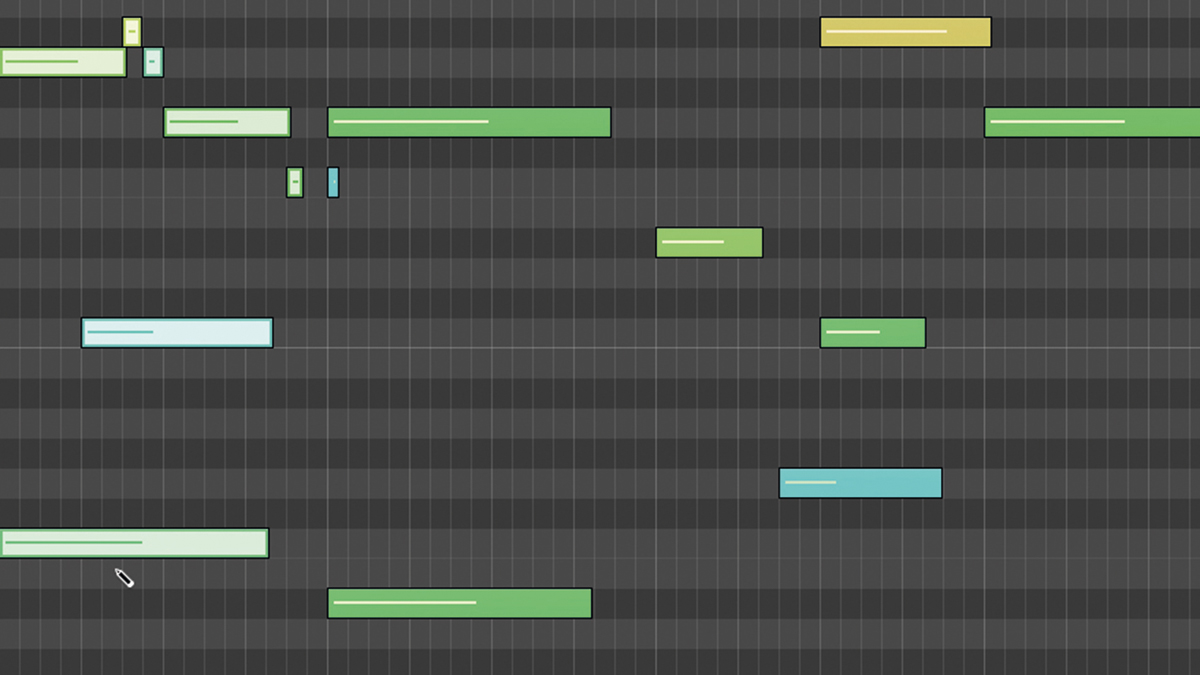

Step 1: In C minor, here is the scale (the bottom note) and the associated ‘third’ note of each chord. If you write a harmony part using any of these bass notes and a melody line from the notes above each one, you’ll find that you can’t go too far wrong.

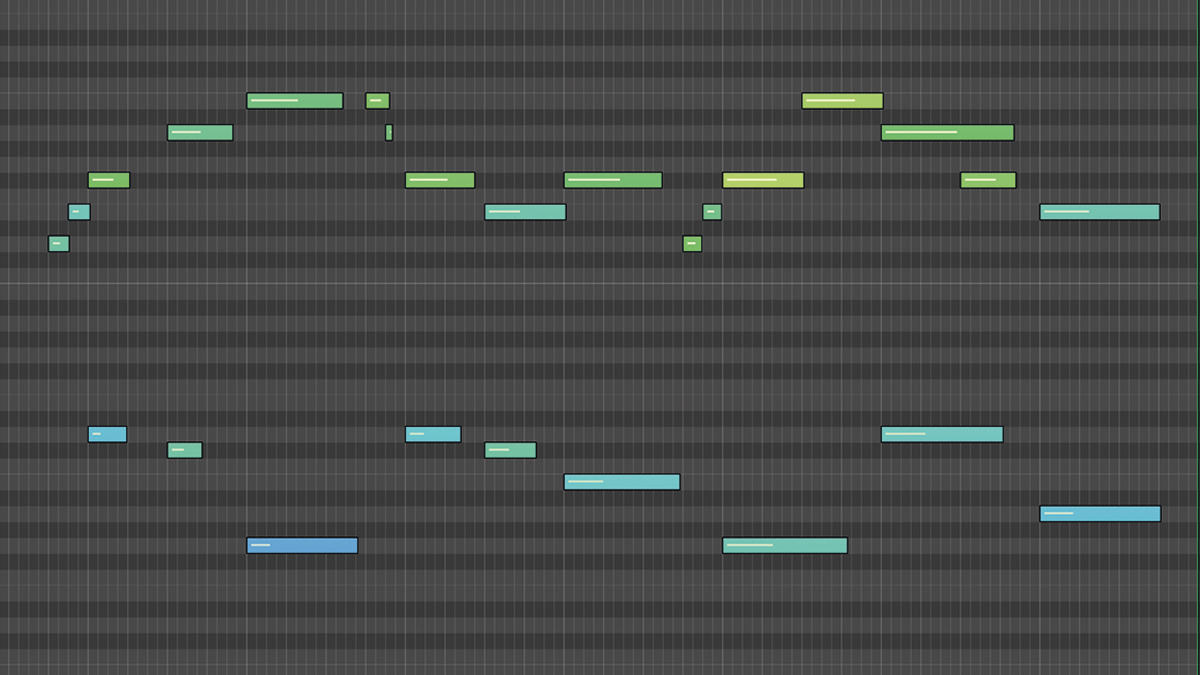

Step 2: This melody is a good example. We’ve called it ‘safe melody’ as all of the notes and the supporting chords come from the options listed in the chord set in Step 1. The melody is slightly melancholy with no surprises. It’s very comfortable and a little predictable.

Step 3: Here, things go a step further. Most of the chords are from within the chosen set, but we’re choosing to warp one chord – the one where F plays in the bass – and make this an F major by changing the ‘expected’ A flat above it to an A. Suddenly the harmony provides a ‘lift’.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.