How one American stage tech coped to survive during a worldwide pandemic

What do you do when your entire lifestyle and career are halted with no sign of return in a worldwide crisis? Rigger Kaela Chaffin moved sideways

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the pandemic hit, the live music industry came to a sudden and complete halt. Almost overnight, the live event business was suddenly non-existent. According to Save Live Events Now, there are over 12 million live event workers in the U.S. alone, and 77% of those people lost 100% of their income.

Additionally, 97% of all contract workers (also known as Freelancers or “Gig Workers”) lost their income entirely.

As time passed, many people in the industry began to evaluate their options. Freelance gig workers were among the first to pivot into finding long-term band-aids for the situation at hand. One of those people is Kaela Chaffin, a 30 year old independent contractor from Springfield, Missouri who works as a skilled freelance tech in concert building.

‘Re-skilling’ became an emotive topic during the pandemic – should people in the arts have to retrain to make a living? Don’t they also deserve the support offered to workers in other industries? – but what Kaela did to survive the pandemic exhibits some of the true characteristics of creative adaptability: she recognised that the situation had changed, and then she created an alternative path.

For Kaela, concert building and rigging was not just a job. “It was my dream," she says. "When I was 14, I signed up to be a tech in Theatre class and I just fell in love with it. Creating stories and experiences for people... I fell for it, hook-line-sinker from that point forward.”

After college, she was hired by a local theatre in Springfield, Missouri and by 2018, at age of 26, Kaela made the jump from local to national, flying out and building stages for the likes of Tom Petty, Billy Joel, Elton John and the Foo Fighters, to name just a few.

“I was just so gung-ho that sexism didn't even affect me at all,” she says, “but I also feel that I was very lucky. In our little niche of Springfield, Missouri, my mentors understood naturally what I was about and trusted me. It was a natural brother-sister situation.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"There is a lot of sexism in the industry – the old Road Dog ‘this is a man's industry’ mentality. I noticed, mostly older dudes, just had this old mindset that they didn't want to shake. I was just like, Well, we have the same goal here, so you can either listen to me or you can get the fuck out, I guess.”

Fast forward to March 2020, and Kaela was heading into the busiest touring season (Spring to Fall 2020) of her life. She was in San Francisco when the city “went red”, heading for Seattle that next week. And then “Seattle shut down entirely.”

One of her two main employers, a touring dance company, also shut up shop. And then the second cancelled tours for Guns N’ Roses and Justin Bieber. “Everyone was prepping for the busiest summer, and then all of a sudden it was just gone... It was very intense. I knew that I was going to have to file for unemployment, but there was also no guide book on how to apply and do a multi-state multi-employer claim for gig workers.”

Gig workers are independent contractors and not in any unions. This means that they are each treated like their own self-employed business. And the laws vary state-to-state. “I know musicians had the same scenario: you'd call and lose hours trying to talk to somebody who just didn't understand. I had three employers in four different states, and I'm also an independent contractor.”

After applying in one state, Kaela learned she would be receiving the equivalent of 20% of her normal weekly pay. She quickly realised that this would not be a viable solution.

“Thankfully, I had some savings to get by, but I had also just moved to a new city. I used the time to look at the career that I had built, and if there was any way to spin it to continue on. Like: ‘Let's write out your attributes and what you're good at doing and see if they can just kind of be moulded to a different industry.’ And I got serious about looking for work.”

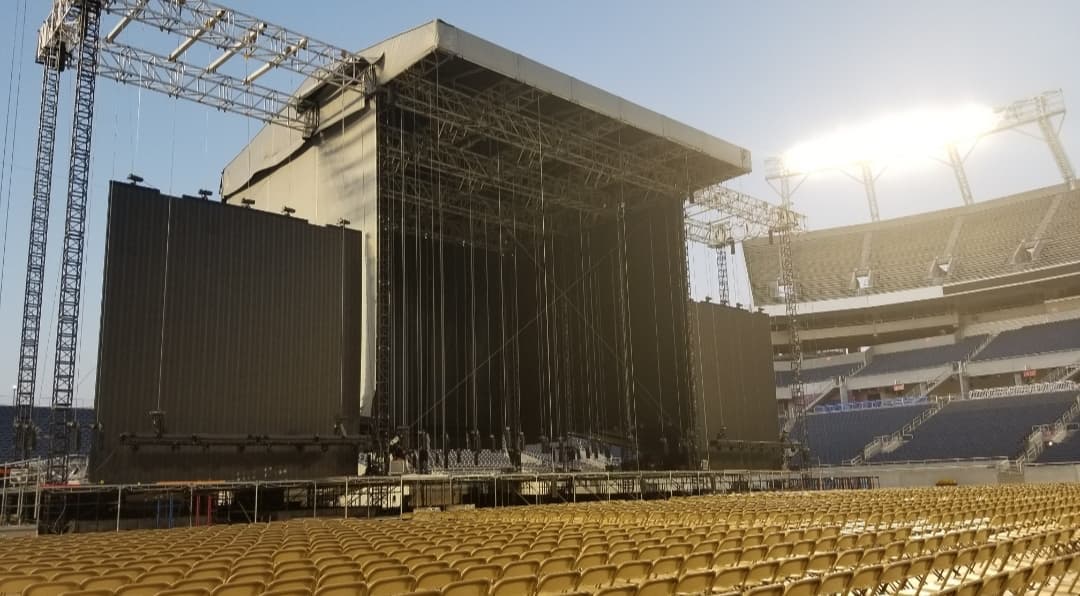

After a few weeks of searching, Kaela got a job as a solar panel installer job in St. Louis. She’s no lightweight when it comes to dangerous jobs. The life of a rigger is serious business. The roof structures they build can be upwards of 70 feet tall, and involve climbing the grids at the top of the structure to move around. The crews are clipped into what they call “Life Lines”.

“You have to have a lot of balance and not be scared of heights, because everywhere you look, there's a negative space where you can fall, so you have to be good with just knowing your space and making sure you're tied in at all times, regardless of the situation.”

The rigging job, similar to solar, requires not only having body and spatial awareness, but an intense amount of attention to detail and safety.

“With the rigging and structure building, I'm just climbing with my own body, and if there's anything heavy, it's on a rope beneath me. With the solar company, they'll literally just throw a solar panel – which can be as big as a door – up on their shoulder and lean it against their head. Then climb up the ladder and step onto what could be an icy roof during the winter. It was an eye-opening and humbling experience. You're used to being on your game and at the height of your knowledge and It brought me right back to zero, learning a brand new industry.”

Not only did Kaela adapt to a new work environment and skill set, but earning respect in another male-dominated world.

”On my first day, the guy who ended up being my lead for my team was just like, ‘I saw how you held a power drill, and right there I could tell that you knew how to use power tools.’ They understood my work persona and that I could handle myself.”

Many crew have not faired as well with no safety net of insurance, savings, or steady work. The bigger question brewing in the industry right now is… should this be the way? As venues and concert promoters lose money on cancelled events, there seems to be no immediate relief in sight. There have been a few grants for venues, artists, and gig workers such as Save Our Stages, Music Cares and LiveNation’s Crew Nation. But the benefits of these programs are extremely limited.

Kaela worked at the solar panel company for nine months, starting late summer and working through the winter until the spring of 2021 as events started to come back in parts of the United States. Despite the potentially bleak outlook, Kaela remains resilient and hopeful.

“I feel like it's taught me to be aware, that I need to be multi-faceted to be able to switch gears into another industry, if need be. You don't wanna wish it on anyone, but I am happy to know that I can get through something like that. It makes you feel like you can handle whatever else comes our way.”