Then play on: the story of Fleetwood Mac guitarist Danny Kirwan

Bernie Marsden, Jeremy Spencer and more reflect on the underrated six-stringer

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

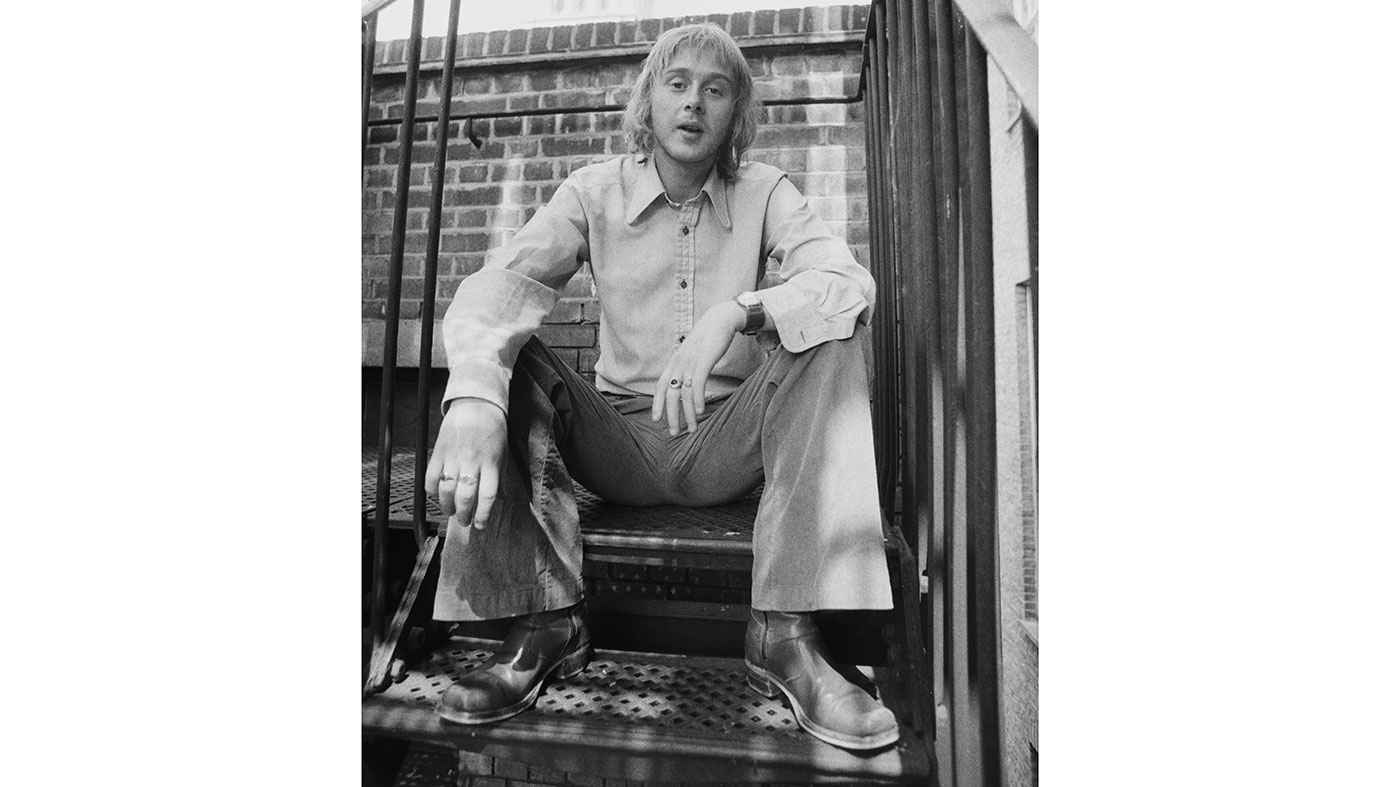

From his seismic contribution to early Fleetwood Mac to his untrumpeted death in June, Danny Kirwan was a mysterious, maddening and misunderstood cult hero. With exclusive testimony from former bandmates and the guitarists keeping his songs alive, this is the story of a musician touched equally by genius and madness.

For the nation’s daydreaming teenage guitarists, with designs on joining Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, the music papers of August 1968 held black news. They had already looked on enviously as Green welcomed the mischievous slide-guitar wizard Jeremy Spencer into London’s preeminent blues lineup. Now, this latest headline of the newest guitarist twisted the knife.

Danny looked so clean and fresh. But his playing was a revelation

Bernie Marsden

“I adored Fleetwood Mac,” remembers Bernie Marsden, then 17, and a decade from his Whitesnake breakthrough. “I would go all over to watch them. And now, suddenly, I was reading in Melody Maker that a new guitarist had joined. I already thought they were the perfect group. They didn’t need an 18-year-old guitar player. And how dare they get a guitar player the same age as me! Why didn’t they ask me, y’know? So I wanted to hate Danny Kirwan…”

But a few nights later, as he packed into the crowd at Dunstable’s California Ballroom, Marsden fell under the newcomer’s spell, gaping at the precocious touch that had whisked Kirwan from his inauspicious Brixton roots, through the formative power-trio Boilerhouse, to the head of the blues scene.

“What turned my head that night,” he remembers, “was seeing this fresh-faced blond teenager up there on the stage, in-between these wizened professionals – who were probably only about 22 themselves at the time. It was so obvious they’d been on the road for a long time, because Danny looked so clean and fresh. But his playing was a revelation.”

Rarely has there been such a disparity between a guitarist’s appearance and his character and abilities. In his recent photobook, Love That Burns, Mick Fleetwood noted that Kirwan “might have been mistaken for an innocent church choirboy, but he would play the hell out of his guitar, deep in the trenches of the darkest grooves.” Ostensibly Green’s protégé, the newcomer was militant, obsessive – and by his own admission, “a bit temperamental” – often diving so deep into the dark heart of the material that he would weep while playing.

“Danny had a beautiful delicacy,” says Little Barrie bandleader Barrie Cadogan, “but he could be very aggressive. There was a frustration in his playing. There was a sorrow in it. Danny was barely 18 when he joined, but he just had a touch that was all his own, and it was equal to anyone.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

No filter

For those lucky enough to pack into a sweatbox club in the late-60s and stand inches from Kirwan’s coruscating fingers – dancing across the neck of a Watkins Rapier – the emotional gamut of his playing was a gut-punch. Even those who didn’t – like Wolf People’s Joe Hollick – feel the shiver, half a century later.

“Danny is one of those players that you almost feel like his brain is wired direct to the speakers, there’s no filter in-between. Whatever emotion he was feeling, that’s what the listener hears. If you listen to bootlegs of the same song, his dynamic range of emotion is so wide and varied. What really strikes me is the sheer ferocity of his attack and his vibrato, and then the ability to be so delicate, so soulful.”

Danny had a very important counterpoint to Peter on Albatross

Bernie Marsden

His fretwork alone would have vindicated Kirwan’s place in Mac, completed by drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie. The revelation was that he also had a beguiling singing voice and a headful of songs, bringing a palette of influences that roamed from the rhythms of Roaring Twenties speakeasies to the Italian-American tenor Mario Lanza – and nudged the Mac out of a formula that was already starting to feel a little stale on 1968’s second album Mr Wonderful.

“His impact was significant,” Spencer tells us. “The original four-man lineup was Chicago blues-driven, and Danny’s addition and contribution quickly took the music in a different direction. Besides being a blues player himself, his main influences at the time were The Beatles and Cream.”

So began the sea-change. Although credited to Green, one of Kirwan’s first contributions was 1969’s Albatross, his blissful touch on this UK No 1 single playing off against the bandleader’s languid lines.

“Danny had a very important counterpoint to Peter on Albatross,” explains Marsden. “Everything that Peter put on that basic track was beautifully reflected by Danny’s part”.

Flip the original vinyl and you found the younger guitarist’s wiry adaptation of Jigsaw Puzzle Blues as the B-side. But his influence really tightened with that year’s unprecedented Then Play On album, to which he contributed seven songs, included the thrumming spaghetti-western blues of Coming Your Way and the autumnal, Beatles-worthy When You Say.

Dual Pauls

With Spencer less involved, the main event was the evolving ying-yang between Green and Kirwan, both butting heads on twin ’50s Les Pauls, but with a markedly different thumbprint. “It would have been so easy for Danny to mimic Peter, because he was such a force as the bandleader,” says Cadogan. “It’s interesting that those guys had the same gear - a Gibson Les Paul - but they sounded so different.”

“That whole long-bend thing; I’ve always had the theory that Danny developed that just so he’d be different to Peter,” picks up Marsden. “And that’s a very wise move, because who in the heck could play like Peter Green in that period? In my mind, I think Danny developed that so you could distinguish them on record. Which of course, you always could after that. I mean, that one lick in Man Of The World [1969] which he plays in the middle - it’s so obviously Danny.”

It’s interesting that Peter and Danny had the same gear - a Gibson Les Paul - but they sounded so different

Barrie Cadogan

Green’s burnout of the early-70s is well-documented now: the rambling interviews, the messianic robes and the LSD. Less explored is the period following the talismanic bandleader’s exit, when Kirwan found himself holding the reins.

“I did a show in Oxford with Fleetwood Mac in about 1970,” recalls Marsden. “Peter had gone by then, and Danny was full-on that night, because it was only him and Jeremy, so he was in the guitarist role. It was still very much Fleetwood Mac, without Peter Green, which everybody thought would never happen, but it did. Danny was really good that night. He had a three-pickup black Les Paul. I think that choice did have a bearing on how he played, how he sounded. He played pretty loud and he’d get that real solid sound.”

Live was one thing. The more daunting challenge of recording another studio album without Green began at Kiln House, described by Fleetwood as a “frugal, artsy farmhouse” in Hampshire. When the album of the same name emerged in September 1970, Kirwan was rampant, contributing the warm roots of Station Man, the brittle Neil Young-esque rock of Tell Me All The Things You Do, the McCartney-mellow Jewel-Eyed Judy and the jangled instrumental Earl Gray - to offset Spencer-penned-50s homages like This Is The Rock.

They had survived, but the drummer’s verdict in Love That Burns was lukewarm: “We made that very unusual, charming little album, where Jeremy was in a world with Danny. But they weren’t prepared without our big leader. It’s sort of a cool little album, but we were floundering.”

Kirwan had other aces to play. In 1971, the guitarist spliced his hypnotic licks with lyrics from the poet W.H. Davies to create Dragonfly: an underrated single that Green would describe as “the best thing [Danny] ever wrote”. That same year, with Spencer departed but Californian guitarist Bob Welch coming aboard, the Mac hit back with Future Games, Kirwan supplying the dreamy psychedelia of Woman Of 1000 Years, the country-flavoured Sometimes and Sands Of Time’s tumbling arpeggios.

Drink, drugs and paranoia

Better still was 1972’s Bare Trees, illuminated by the glorious Sunny Side Of Heaven, the propulsive Child Of Mine and the pounding wah-led experimentation of Danny’s Chant. Already, you could hear the band that Fleetwood Mac would become and the distant ringing tills of the Rumours era. “His creative originality most certainly helped to bring new life to Fleetwood Mac and consequent commercial success,” says Spencer, “and I don’t mean this disparagingly.”

But by then, Kirwan was coming apart. Drunk, paranoid, barely eating and at loggerheads with his bandmates, the guitarist’s Fleetwood Mac career reached a shabby end during the US tour of 1972, as an argument over Welch’s tuning boiled over. Kirwan smashed his own instrument, refused to take the stage and was fired.

When truly playing blues, you need a balance of positive energy, if you like, to counteract the possibility of being swallowed up

Jeremy Spencer

“It was something we simply could not forgive,” wrote Fleetwood. “Danny had broken the code that said you don’t hang your bandmates out to dry on stage.”

For just a heartbeat, Kirwan threatened to segue into a decent solo career with 1975’s melodic Second Chapter. But 1976’s Midnight In San Juan brought diminishing returns, and he was barely involved in 1979’s Hello There Big Boy!, an album even producer Clifford Davis deemed “so bad”. Any chance of slow-burn success was nixed by Kirwan’s reluctance to perform live.

“I’ve got all three of those solo albums,” sighs Marsden, “and every one of them has at least two gems on there. But I don’t think people really got into them at all.”

So began Kirwan’s withdrawal from the music industry and terminal decline. Dark whispers told of him lurking in a Brixton basement flat, kept alive by his royalty cheques. Darker ones placed him at a London homeless hostel.

“It’s hard to say what caused Danny’s later problems,” considers Spencer. “Some blame the drugs and the alcohol, which in some ways enhances inherent psychological problems, and him being a ‘sensitive musician’ to boot. He was jittery and nervous, and the pressure became too much for him. He once said in a rare interview from the 90s something along the lines of playing the black people’s music requiring too much of you, and he regretted touching it. In some ways, I agree; when truly playing blues, you need a balance of positive energy, if you like, to counteract the possibility of being swallowed up in the ‘Green Manalishi’ of deep, dark depression.

A legacy

“We lost regular contact after I left the band in 1971,” Spencer continues. “Although we did meet for coffee in London, 1978, and did not meet again until the early 2000s, when my wife and I met him, his ex-wife Clare and their son Dominic for lunch in London. It was pleasant enough, even though he was in his own world.”

Kirwan had long left the headlines when he died on 8 June 2018, aged 68, following a bout of pneumonia. The obituaries were cursory, most editors preferring to lead their sections with tributes to Peter Stringfellow. But to those who had traced Kirwan’s career, the loss was keenly felt.

I just hope he knew that there were plenty of people out there who did really love what he did

Barrie Cadogan

“It angers me, really,” admits Cadogan. “There’s guitar players that get a lot of credit - sometimes they get too much. Like, they’re hailed as great blues players, but a lot of it is like a Hard Rock Café Disney-fied version of what it really is. It’s like tourist blues. It’s frustrating that Danny never got the credit he deserved in his lifetime. I just hope he knew that there were plenty of people out there - maybe not on a mass scale - who did really love what he did. I prefer his playing to a lot of people who were much more well-known.”

“I was devastated when I heard that Danny had died,” says Hollick. “I hoped one day we might have got to see him play again, and somewhat selfishly, I always imagined being able to let him know how many musicians from my generation look up to him and hold his playing dearly.

“He’s criminally overlooked by the general public, and therefore popular music, but I actually think he isn’t underrated at all within the circle of musicians, music obsessives and record collectors. I’ve found it incredible how I can go anywhere in the world, and if you mention the name Danny Kirwan to someone who you think shares similar tastes to you, their eyes light up. I constantly use his music as a sort of healing tonic. I can never, ever get tired of hearing him play.”