Engineer Andy Johns on recording and mastering Led Zep IV: “I put the tape on and the first song goes by and sounds bloody awful. Then the second one comes along and that’s really horrid, too... Pagey should’ve fired me at that point"

"Pagey was going on about seeing ghosts on the stairs and we were like, ‘Oh yeah right, Jimmy!’"

By the time Led Zeppelin holed themselves up in a dilapidated former Victorian workhouse at the beginning of ’71 to cut their fourth album, they were on the verge of becoming one of the biggest-grossing live acts of all time.

At the end of the year, gig revenues of $100,000 (£62,000) in the US were commonplace, running hand-in-hand with the notorious drug- and booze-fuelled orgies and excess that seemed to follow the band around wherever the road took them.

Musically, Zep had already produced three superb, virtuosic albums – I, II and III – across ’69 and ’70, but their hate-hate relationship with the press on both sides of the pond was showing no signs of abating.

Moreover, the predominantly acoustic and folk rock approach of Led Zeppelin III had not only prompted a further flurry of lukewarm write-ups from the media, it had also alienated some of Zeppelin’s hardcore fanbase, although copies still shifted by the stack load.

By the fourth album we collectively agreed on what the visual aspect should be: total anonymity

Jimmy Page

The response of Messrs Page, Plant, Bonham and Jones was to carve out an eight-track platter that showed off every nuance of their eclectic musical ingenuity. This included the axe-burning stomp rock of Black Dog and Rock And Roll, the mandolin-drenched folk tones of The Battle Of Evermore, the gentle beauty of Going To California, the layered “guitar army” orchestration of Stairway To Heaven, and the echo-laden blues-rock majesty of When The Levee Breaks.

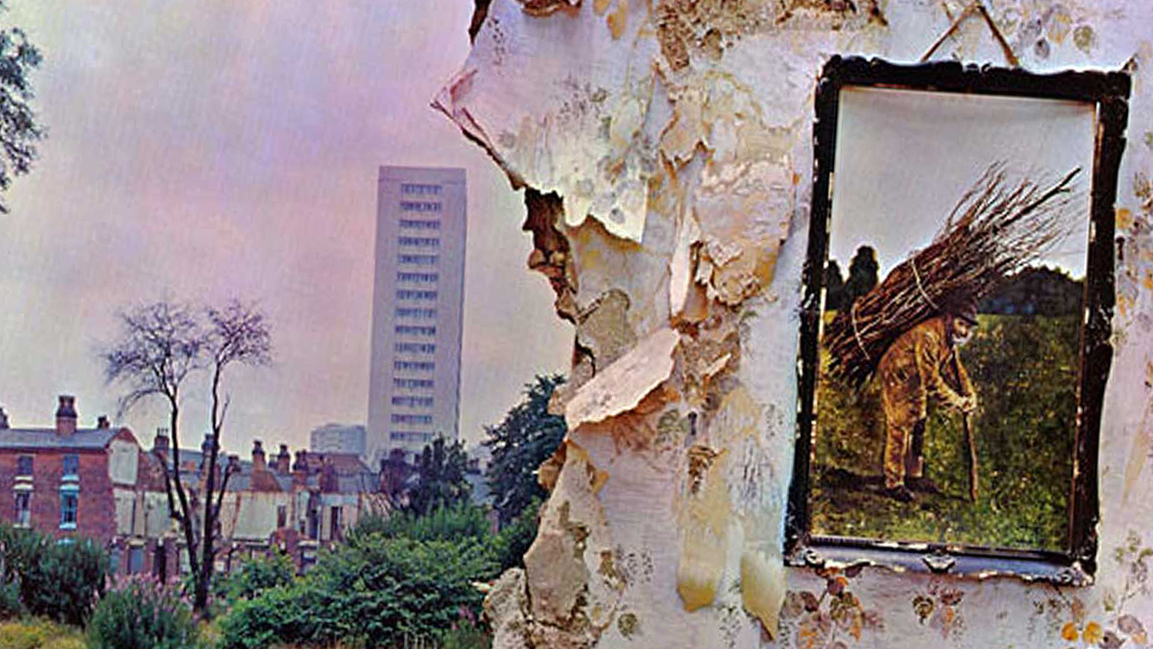

Meanwhile, the LP’s cover included no title, no track listing and no reference to the group aside from symbols representing its members on the label and spine. “By the fourth album we collectively agreed on what the visual aspect should be: total anonymity,” Jimmy Page later told Mat Snow. “It said, ‘Forget everything from the past – this album is moving towards the future; just listen to the music!’”

While the record that came to be known as Led Zeppelin IV once again failed to light up the review sections of the day, it’s now sold over 37 million copies and is deservedly regarded as not only Led Zeppelin’s crowning long-playing achievement, but also one of the greatest guitar albums ever committed to tape.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Writing for IV had kicked off in October 1970 at Bron-yr-Aur, the spartan cottage in South Snowdonia where Page and Plant pieced together much of Led Zeppelin III. Tracks that started to evolve during this brief sojourn included formative sections of Evermore, Misty Mountain Hop and Stairway, but the real purple writing patch would come at Hampshire’s Headley Grange – the aforementioned former Victorian poorhouse – where the group had first been to record elements of III.

That place was very broken down with springs sticking out the couches and all that kind of stuff

Andy Johns

“That place was very broken down with springs sticking out the couches and all that kind of stuff,” engineer Andy Johns tells TG. “And Pagey was going on about seeing ghosts on the stairs and we were like, ‘Oh yeah right, Jimmy!’”

“It was a pretty austere place. I loved the atmosphere of it,” Page told the BBC of his time at Headley Grange. “I really did personally, but the others got a bit spooked out by it.”

Andy Johns was only 19 years old when he recorded Led Zeppelin IV, but he’d already engineered the group’s third LP and parts of their second, as well as recordings by the Rolling Stones, Free and Blind Faith. It was Andy’s idea to shirk more traditional studio setups, although his initial suggestion didn’t curry much favour with Jimmy Page, who was once again in the production hot seat.

I’m not giving Mick Jagger £1,000 for some old mansion

Jimmy Page

“I was working with the Stones’ recording truck a lot at Mick Jagger’s house and I was getting some great sounds,” said Johns, when we spoke to him for the 40th anniversary of the album’s release.

“So I mentioned to Jimmy, ‘Look, we should use the truck,’ and he said, ‘OK, how much does that cost?’ ‘Well, the truck’s about £1,000 a week and so’s Mick’s house.’ [And Page said] ‘I’m not giving Mick Jagger £1,000 for some old mansion, I’ll find somewhere else!’”

Johns duly arrived at Headley in the middle of January 1971, complete with the truck and Ian Stewart, the van’s resident engineer and ex-keyboard player for the Stones. Stewart would end up playing piano on both Rock And Roll and Boogie With Stu, the latter of which was recorded during the week-long Headley stint, but wouldn’t see the light of day until 1975’s Physical Graffiti album.

Parking at the front of the house, they piled wires through the windows of the drawing room, which would be the main recording space for the album.

“The amplifiers were all over,” Page said. “The two sets of amps were in the other rooms and other parts, such as cupboards and things. A very odd way of recording, but it certainly worked.”

However, Johns can’t remember recording amps in any space other than the drawing room. “That’s one of the reasons that I put John [Bonham] out in the lobby,” says Andy in reference to the moment he shifted Bonham’s kit to the hallway, hung up two mics and nailed the inimitable Levee Breaks drum sound.

“They were all in the same living room space and they would play pretty bloody loud and the sound level would build up tremendously.”

The amplifiers were all over... a very odd way of recording, but it certainly worked

Jimmy Page

Amp-wise, Jimmy was favouring Hiwatt Custom 100s by the time the band came to record IV. “I don’t think there was much AC30 going on,” says Andy. “There was a Hiwatt and there might’ve been a Marshall, but I think it was pretty much Hiwatt with one 4x12, sometimes two of them, and then he had that lovely Les Paul sunburst and also a Telecaster.”

The cherry sunburst ’59 Les Paul Standard in question, bought from Joe Walsh in 1969 for £500, was used by Page on every Zep album from Led Zeppelin II onwards. The Telecaster was undoubtedly the 1958 model that Jeff Beck gifted Jimmy in 1966. Page had stripped down and hand-painted the axe with the famed dragon design in 1967 before using it for the group’s debut.

As far as Led Zeppelin IV goes, Jimmy played it on a number of tracks, most notably the Leslie overdub on Rock And Roll and the awe-inspiring solo of Stairway To Heaven. Johns remembers using a few different microphones “banged on the speaker” during the sessions, including a Neumann U67, a Beyer M160, an AKG D25 and an AKG D12.

The all-in-this-together country vibe of Headley Grange, coupled with flagons of cider, also helped fuel Zeppelin’s songwriting. Parts for Going To California, Misty Mountain Hop and The Battle Of Evermore were developed during “late-night guitar twiddles”.

One evening, Page picked up John Paul Jones’s mandolin for the first time. “Some would go to bed and I would sit up and play quite a bit, and I picked it up and [the Evermore sequence] just came out!” Page said.

“I’d never played one before, the tuning is totally different. There was something about that period. It was a time of great inspiration.”

Johns has similar memories of that creative flow: “There was one song where we were all sitting round the fireplace and somebody started noodling. And I went, ‘Quick, I better get in the truck and record this!’ I forget what the song was, but that was it, it was done.”

Four Sticks was another song that benefited from the creative vibe of Headley. While the core rhythm track was nailed in two takes with John Bonham pummelling the complex beat with two sticks in each hand, Page used the middle section to experiment with layering his axe sounds, a move that he later recognised as being particularly significant.

“I can see certain milestones along the way, like Four Sticks,” Page told Steven Rosen in 1977. “In the middle section of that. The sounds of those guitars – that’s where I’m going.”

Rock And Roll was written, riffed and recorded in just half an hour

The ballsy retro-fest stomp of Rock And Roll, meanwhile, was written, riffed and recorded in just half an hour while the band struggled with the complex time signature of Four Sticks.

Led Zeppelin only had six days of recording time with the truck at Headley Grange, after which point they traversed up country to finish the album at Island Records’ Basing Street studios in Notting Hill.

It was here that two of the album’s most loved tracks, Black Dog and Stairway To Heaven, were put to bed. The former tumultuous, stop-start album opener was named after a mysterious black Labrador that shuffled around Headley Grange during sessions.

The song came out of a riff written by Zep bassist and multi-instrumentalist, John Paul Jones. “I recall Page and I listening to Electric Mud at the time by Muddy Waters,” Jones would later tell Dave Lewis. “One track is a long rambling riff and I really liked the idea of writing something like that – a riff that would be like a linear journey. The idea came on a train coming back from Page’s Pangbourne house. From the first run-through at the Grange, we knew it was a good one.”

Jones had arranged numerous hit records on the '60s session scene before joining Zep – including She’s A Rainbow by the Stones – and performed the same duties for Black Dog, which originally had a virtually impossible 3/16 time signature. Johns is rightfully proud of the direct guitar sound.

“I was trying to steal this sound from [legendary US producer and engineer] Bill Halverson,” says Andy. “I ran the guitar direct into the mixer and used a couple of Universal limiters. I just cranked the hell out of them, making the mixer distort, making those distort and then we double-tracked it.

"I said, ‘Let’s do one more, Jimmy!’ so we got one up the middle… The current level on those guitars was phenomenal, just amazing.”

During IV’s Basing Street recording bout, overdubs were added to many tracks, including Sandy Denny’s vocal on Evermore. Throughout the recording and mixing stages, both Page and Johns really came into their own creatively as producer and engineer respectively.

The harmonica-wailing blues rock thump of IV’s album closer, When The Levee Breaks, is a case in point. “Jimmy always had a great sense of arrangement and also a lot of ideas about sounds,” explains Johns. “He was always wanting to experiment. On Levee Breaks, it was his idea to phase the vocal and it had been my idea to put the drums out in the hallway… and also to put Robert’s harp through a ratty old [Fender] Princeton amp with one speaker missing and the tremolo on it.”

Now Pagey should’ve fired me at that point, that’s what I would’ve done… but he didn’t

In early February ’71, Johns and Page flew to LA to spend a couple of weeks mixing at Sunset Sound. Despite his appreciation of Sunset’s facilities, Johns had an ulterior motive in heading to the City of Angels – a young lady. Unfortunately, Sunset had changed their monitors and when the pair returned to Olympic Studios in London to play the album to the other guys, they realised the inferior speakers in LA had ‘lied’ about the sound.

“I put the tape on and the first song goes by and sounds bloody awful and then the second one comes along and that’s really horrid, too,” says Johns. “Now Pagey should’ve fired me at that point, that’s what I would’ve done… but he didn’t. He said, ‘Come on, let’s go back to Island and mix it properly’.” That remixing session would be the last time Johns worked with the band.

Led Zeppelin IV was eventually released in November 1971 after extensive remixing and a prolonged fight with Atlantic Records over the cover art. While critics on the whole still slagged off their nemeses, the world’s denim-and-leather clad hordes lapped it up. Zep went on to become the biggest rock band the world’s ever seen and, more than 50 years on, IV remains their crown jewel.

Long live the dinosaurs.

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers...

- GEAR: We help musicians find the best gear with top-ranking gear round-ups and high-quality, authoritative reviews by a wide team of highly experienced experts.

- TIPS: We also provide tuition, from bite-sized tips to advanced work-outs and guidance from recognised musicians and stars.

- STARS: We talk to musicians and stars about their creative processes, and the nuts and bolts of their gear and technique. We give fans an insight into the craft of music-making that no other music website can.