The lowdown on 'feel' and 'groove': how they affect your music, plus 8 quick tips to try

Give your productions a more human touch with these practical tactics

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is the difference between everyday sound and music?

We’re surrounded by sounds over which we have no control; traffic noise, environmental sounds, overheard conversations and, of course, the music we encounter when walk into shops, cafés or restaurants, or when cars drive past with their stereos cranked to maximum.

But what is it that separates the auditory experiences we classify as ‘sound’ from those we’d categorise as music?

A popular definition of music is ‘organised sound’; whereby anyone writing or playing music takes control over the sounds they make and, in that control, order and ‘organisation’, random acts of noise-making become deliberate, planned and, therefore, music.

For others, that definition doesn’t go far enough, so we're going to build on that definition and explore why it is that listening to and playing music can cease to be just a listening experience and become something which captures a wider collection of our senses.

Whenever you tap your foot or nod your head in time to a groove, you don’t just hear it, you feel it. And ‘feel’ is the word we’ll be exploring, discovering that it contains an unusual magic.

The emotional arc of feel

Before proceeding with the rest of this article, take a few minutes out to listen to the opening title music to Schindler’s List. It’s a remarkable piece of John Williams’ music, perfectly setting the listener up for the tragedy of the film to follow, with a yearning melody, heartbreakingly performed by Itzhak Perlman.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

One of the things which is so extraordinary about the melody, soaring above the arrangement accompanying it, is how few of its notes are performed perfectly ‘in time’.

Sometimes, the soloist arrives a note early, with slight restlessness, waiting for the orchestra to catch up; at other moments, he only comes to rest on a note after the orchestra has reached a musical conclusion, delaying his own resolution by a few achingly poignant fractions of a second.

There are many examples that we could have given to illustrate ‘feel’ and, no doubt, this is one with heavy emotional resonance. And yet it perfectly illustrates that, rather than undermining a sense of the tempo and flow of a piece of music, this willful ‘playing around with time’, letting the emotional arc of the melody determine exactly where the notes should fall - the ‘feel’ in other words - represents a huge part of the reason why this music, and this performance, is so memorable.

Toying with time

This teaches us something immediately valuable; that using the metronome more as a guide than a dedicated target can free up our musical sensibilities.

The other thing to note in this example is that it also establishes the relationship between the orchestra and the soloist. While the orchestra conforms more strictly to tempo, the soloist is more free and we’re more able to notice his musical gymnastics as they’re performed against a solid foundation.

his also provides valuable insight; in order for ‘feel’ to mean something that’s at all worthwhile, we do need to be aware that a sense of timing is being deliberately toyed with, as opposed to doing so out of poor preparation or lack of understanding.

Going off-menu

You’ll find similar musical devices present across musical genres, whether you favour the frenetic, ahead-of-the-beat urgency of some rap vocalists or the deliberately too-cool-to-keep-up laziness of some jazz and soul artists.

Which raises a third interesting point; namely that ‘feel’ can mean playing ahead of the beat or behind it. Provided that doing so enhances the musical experience of a note or phrase, both slightly speeding up or slowing down a performance can be musically effective, with different emotional responses being triggered by each manipulation of meter.

As electronic musicians, the tools we have at our disposal to ‘post-produce’ feel, by quantising notes or moving them manually to positions closer to the bar-line, are all too easy. Let’s not be in too much of a hurry to make perfect timing a default option at the expense of ‘feel’.

Rushing or dragging? It’s all in the backbeat

In this walkthrough we’ll explore a simple device to shift the ‘feel’ of a groove from ‘fast’ to ‘slow’ without actually altering tempo

It’s always fascinating to discover how even the subtlest shifts in a rhythmic groove can change its feel. Subtly delaying the arrival of a kick drum on the down-beat of a bar can provide a subtle shift which makes a groove ‘relax’, whereas we’ve all heard the difference between ‘straight’ and ‘slightly swung’ hi-hats. In real terms, those swung hats only have to be a fraction ‘late’ to completely change our perception of the groove.

So it also proves with the backbeat of a rhythm, as we’re exploring through the following steps. We’re focusing on the snare sound, keeping our ears trained on how a groove feels when the backbeat is shifted early or late.

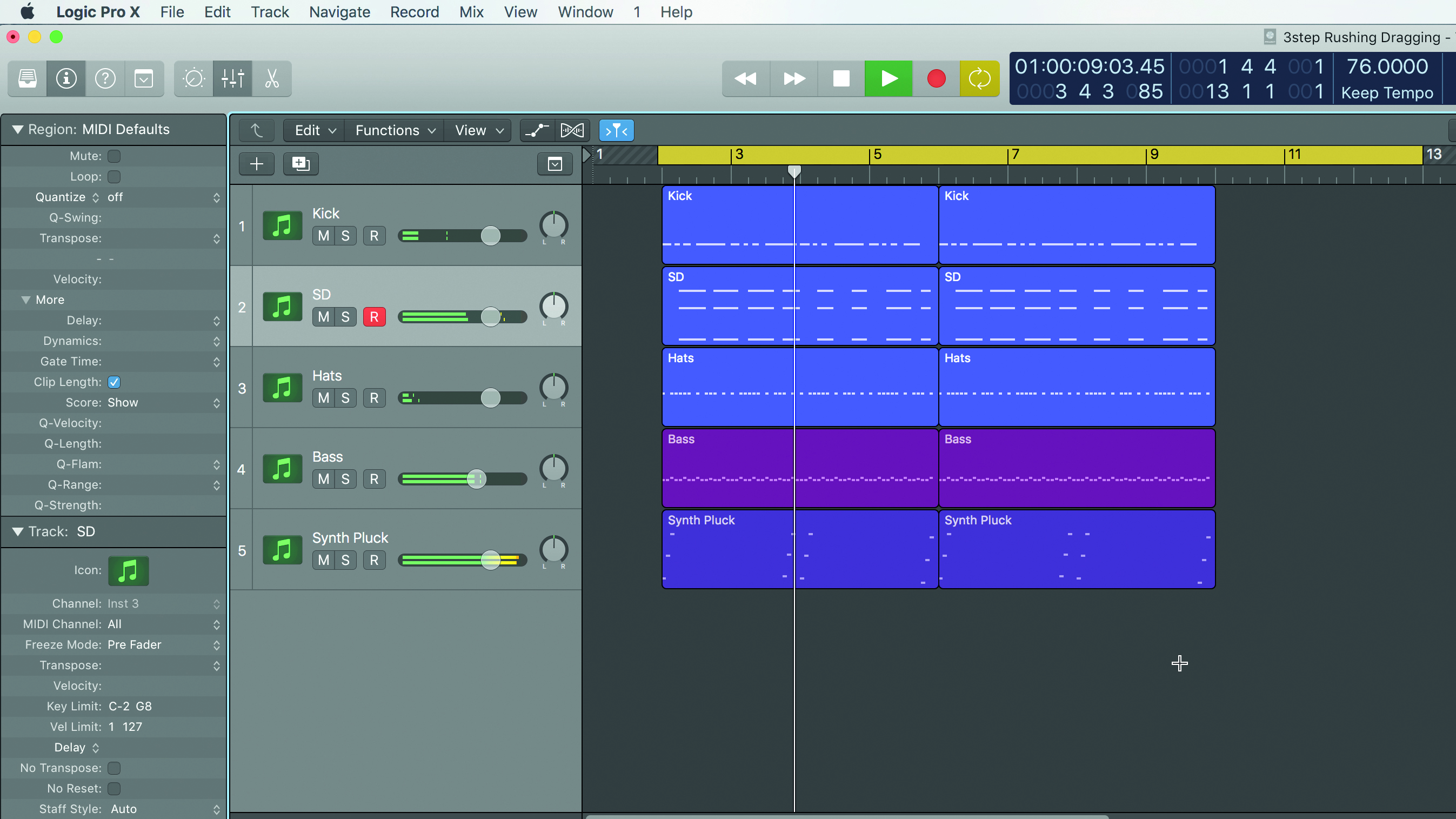

Step 1: Take a groove split into three individual tracks - Kick, Snare and Hats. Against this, program a locked 1/16th sequence as a bassline and add a rising octave synth hook and a 1/4 note delay. Everything is quantised for a completely ‘straight groove’.

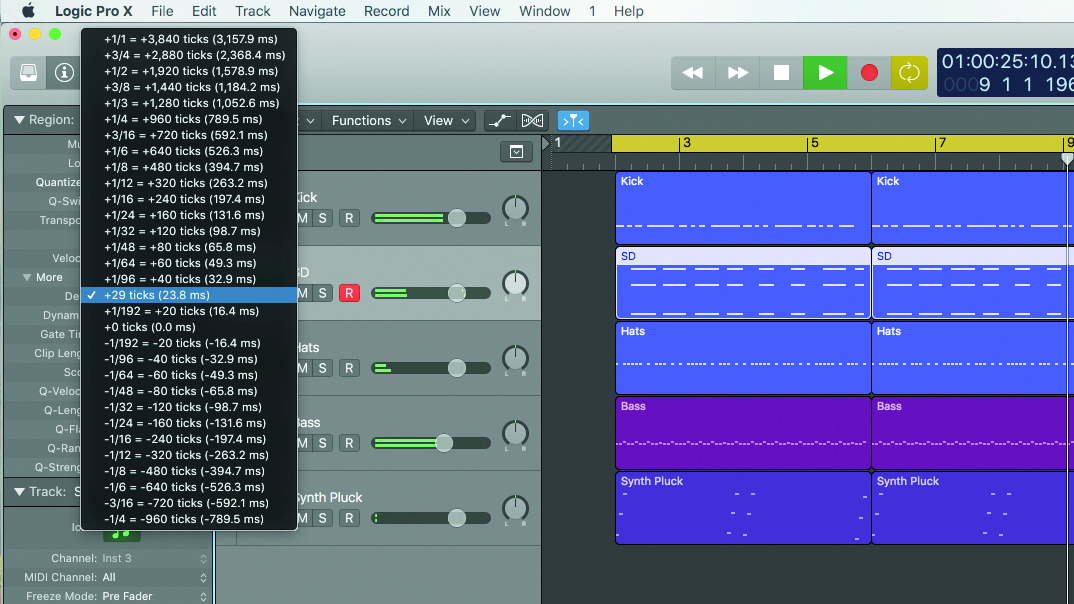

Step 2: We turn our attention to the snare drum and use MIDI delay to offset it by 29 ticks, which equates to 23.8ms. We apply this to hear what happens when our snares deliberately drag. The whole feel of the track is slowed down, despite the tempo remaining at 76bpm.

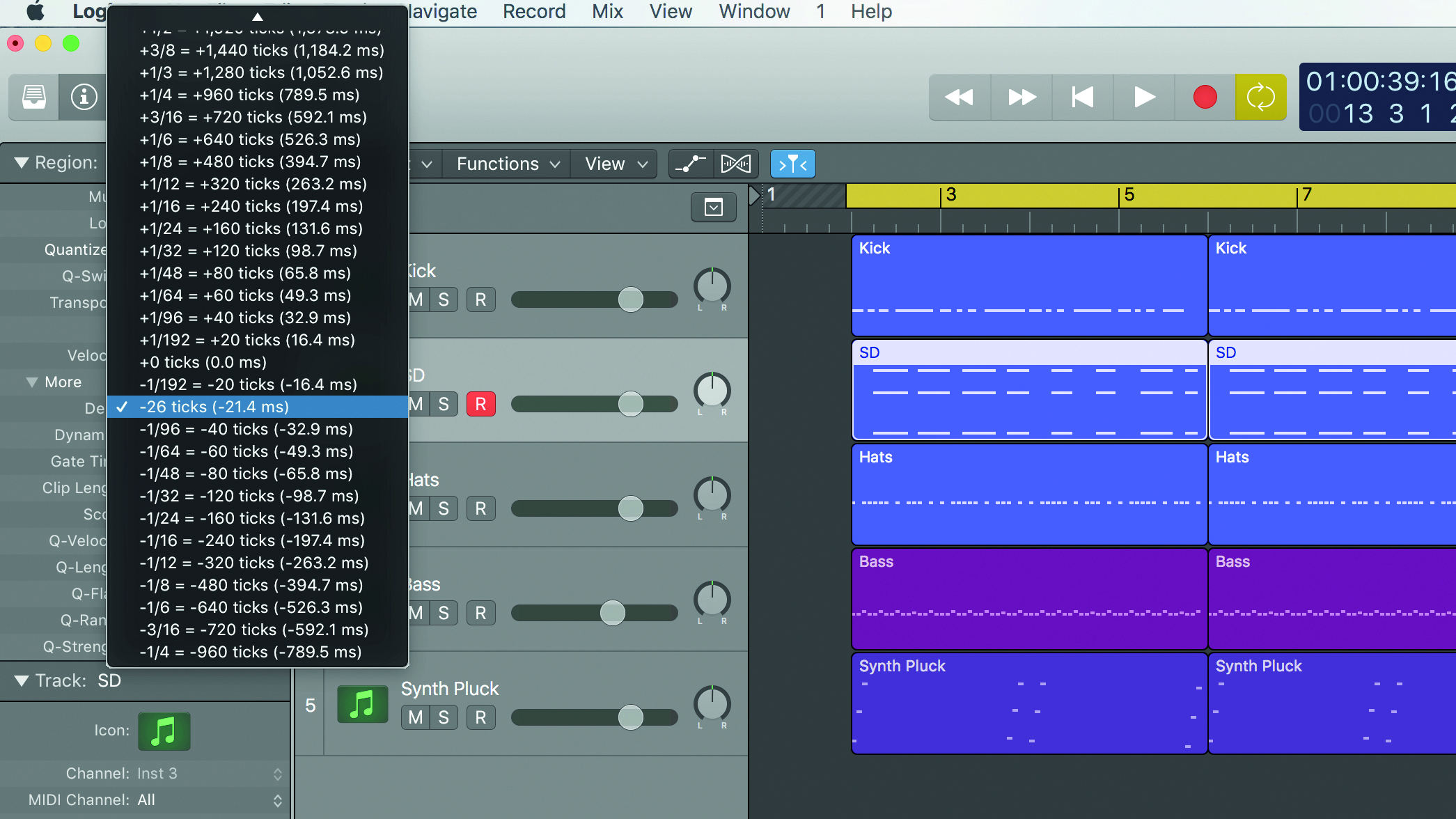

Step 3: Conversely, here’s how the track sounds when the snare drums are brought ahead of the beat. A negative MIDI offset value brings the hits forwards and the value we choose - -26 - equates to 21.4ms. The ‘drummer’ sounds like they’re trying to hurry the track up.

Quick tips: 8 ways to find your feel

1. Practise the keyboard

Too often, we reach for quantising because we don’t feel sufficiently in control of musical performances. Simply using a keyboard for note input isn’t enough. Practise and add a meaningful level of musicality to the notes you choose.

2. Play your drums

Feel is more easily brought to a track if the relationship between your performance and the instrument you’re programming is natural. This isn’t always possible (the MIDI tuba isn’t, to our knowledge, available yet) but it’s true of drum programming.

Buy drum pads, or use your keyboard to ensure you bring feel to the drum and perc parts you program.

3. Listen and learn

Listen to a broad range of music. It’s easy to get ‘conditioned’ by the genres you listen to most. Why not apply the ‘feel’ of, say, a jazz record to your next techno track?

4. Let the feel unfold

One of the problems with quantising is that if you select, say, a 1/16th note as your quantise resolution, every single 1/16th note will adhere to a grid position. Even if you select a value with ‘swing’, you still form a relationship between two notes (one in time, the next a little late) in every single pair of 1/16th notes.

Often, this isn’t how ‘feel’ is created. Groove can unfold over a bar, two bars, four, or eight. By all means build grooves which lock to a recognisable structure, but make the feel unfold over a longer period of time. The results are often more sophisticated and more musical.

5. Make your own quantise templates

As explored, if you create a rhythmic feel which gets your track grooving, one way to dilute that clear foundation is to apply a different feel to the next instrument you add. Imagine quantising one row of 1/16th notes ‘straight’ and another with a heavy swing value and you’ll get an idea of how discombobulating this could be.

One great idea is to create a Groove Template; this will analyse the ‘hit points’ in a groove and make a quantise map of its note positions, which can then be applied to other instruments. In this way, you can very quickly lock a number of instruments to a personalised groove.

6. Make better quantising decisions

Most DAWs make ‘full strength’ quantise value their default choice, so that if you put performed notes in time, they’ll be snapped ‘100%’ to a grid: a shame, as a more diluted form of quantising is often preferable.

By playing a part into your project in real time, your own feel’s DNA enters your track; not something you should surrender. Sometimes, applying quantise but reducing strength to 50% brings errant notes closer to ‘perfect time’ but retains more ‘you’. We hide behind playing deficiencies as a reason to go big with quantise, but be brave and see how it sounds with more live feel retained.

7. Humanise your DAW

If 100% strength kills a performance’s feel, it’s easy to reduce quantise to a region you play in live. But what if you’ve drawn in a line of notes manually, or in step-time, so each one is locked to a grid?

Backing quantise strength down won’t make any difference, so you might well need another of your DAW’s functions instead. The one we’d recommend might be lurking in a ‘MIDI transform’ menu, where you can apply ‘destructive’ changes to MIDI notes. ‘Humanise’ is one such function; letting you make subtle changes to the position, length and velocity of notes in order to inject some subtle variation.

8. Appreciate the power of live performance

For those of us who spend lots of time in studios, on our own, making music intended for SoundCloud, sharing online or a music label, it can be too easy to feel distanced from playing music live. And in this context, we’re not referring to DJing, unless you’re the kind of DJ who overdubs their sets with live musical performances.

Yet there are several good reasons why the live music scene remains popular. One of these nearest the top of the list is the power that comes from seeing performers locked in, contributing to a shared musical vision.

As you probably know, the bass and drum players of a band are collectively referred to as the ‘rhythm section’. This is itself revealing; that through the summed, shared musical performances of these two players, the groove is created. Both in your professional music-making and outside it, be a part of live-music making; there’s nothing like it for nurturing your awareness of ‘musical feel.’

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.