In pictures: Ed Rush and Optical's London studio

The neurofunk kings have still got it after 20 years

Elite squad

Fascinated by London’s Rave scene, Ben Settle (aka Ed Rush) entered the world of production alongside infamous No U Turn label owner Nico Sykes to produce the 1993 drum ‘n’ bass classic Bludclot Artattack. Bidding to become part of the drum ‘n’ bass elite, Settle then teamed up with DJ Trace to help formulate the shifting, sci-fi moods of the genre known as techstep.

In close proximity, Matt Quinn (aka Optical) was recording alongside his brother Jamie (Matrix & Futurebound) while engineering tracks for Grooverider’s Prototype imprint and Goldie’s Metalheadz label. Merging their talents, the duo formed Virus Recordings, dropping the drum ‘n’ bass classic Wormhole in 1998, followed by The Creeps (2000) and their third album, The Original Doctor Shade (2003).

As EDM slowly infiltrated an unsuspecting drum ‘n’ bass scene, Ed Rush and Optical have been well served by their knowledgeable production background, which has enabled them to cross generic borders effortlessly, both in the studio and on the DJ circuit.

Hardware vs software

“I don’t wanna say we’re better than anyone else, but I like to think we can think outside of the way they might do their productions.

“It’s easy to settle on chucking a plug-in in these days and not know why you’re doing it, but we’ve learned a lot about the theory behind it.

Having your hands on real synthesizers helps a lot; in a tactile way you learn how each knob can control the sound – I can play them like an instrument.”

Being good at the basics

“Hardware helps with the basics, learning about basic EQing and finding space in the mix.

“It probably helps with the cognitive links in your brain too, because you’re physically moving things around as opposed to clicking a mouse all day. But it basically comes down to good ideas.

“In a digital environment you can stick 32 compressors on one channel – I’m not saying you’d want to, but with hardware you’re more restricted and that might help you dig a bit deeper creatively.”

Total recall

Matt: “This desk cost a fortune, about 20 grand I think. It’s an Otari Status 18R Mixing Console. We wanted a fully recallable analogue desk and there wasn’t such a thing in those days, so we had this custom built. It does actually recall mixes just for the purposes of being able to do more work on them.”

Ben: “Personally I always thought it was a bit clean-sounding. We had to add so much grit to the music we were making back then to make it pleasing to the ear. Now we use a Mackie 32-channel mixing desk.”

Matt: “We come back to it quite a lot. It’s pretty rubbish really, but in a way that’s the good thing about it; you just drive up the gains to the maximum, turn all the EQs up and it gives you some nice, crazy distortions.

“It’s very noisy, like a lot of the gear we have. If you want to mix on it you’ve got to have a perfect signal path and all the wires have to be exactly the right length.

“You have to take a lot of time and care in wiring up a studio if you want to get a great result out of it because there’s quite a lot to mixing in analogue.”

Remaking sounds

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t really use our sample libraries from the E-mu and all that other gear because when you port those sounds into a computer they sound pretty flat and dead.

“We’ve had to remake a lot of those sounds to fit the way that a computer works and to make them unique to us, but did it with a few processes and tweaks.

“We have days of making sounds and getting them all stacked up, because when we’re writing songs we’ve got to be really quick to get a good vibe – if you’re having to stop all the time to create sounds you might as well go home.

“At the end, you can polish it all up and bring out the characteristics of what you’ve got going.”

Preamped

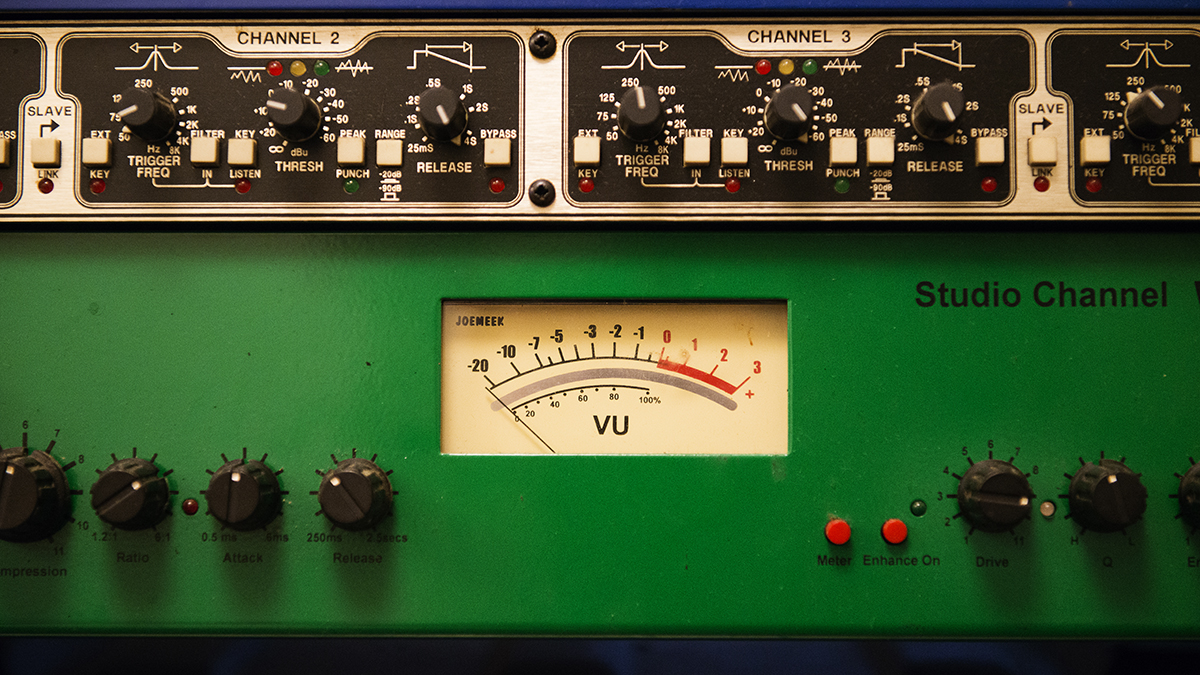

“This top one is the Oberheim GM1000 preamp; it was made by the guitar company Viscount and is pretty good at making stuff sound like an ’80s Rock guitar.”

“We've got the Focusrite Green EQs because they’ll make the sample channel sound more chunky and solid, which sounds amazing. But you have to have a gate on it too otherwise the audio will drown out half the song.”

The rack

“Then we use this TC Electronic FireworX multi-effects unit, which has filters, chorus, delay and a vocoder on it. We use the pitchshifter quite a bit too because we’re always having to pitch stuff down. When people are playing drum ‘n’ bass records, they tend to speed them up.

“We also use the TC Electronic Finalizer, a mastering processor that allows you to maximise songs really loudly; this was before it became easy to do it all in the computer. Then we have the Alesis MidiVerb 4 and the Lexicon Alex, which is a better version of the Lexicon MPX1.We use them for basic reverb and delay and find that those really simple effects are all you need to make stuff sound good.”

True grit

“The one I use the most is probably the Focusrite ISA430 Producer Pack channel strip, because it has a microphone preamp with three different effects that cuts pops out and will compress and EQ on the recording side before it hits the computer.

“It’s actually taken from bits of a Neve desk; they strip them out, put them together in a box and reset it. I could have loads of really high-end stuff and it would be fun but we’re not looking for pristine pop perfection; we want grit and distortion, and you have to use medium-to-cheap gear to make that really happen.”

Sequential Circuits Pro One

“I’ve had loads of different Sequential Circuits synths, but my favourite is the Pro One, which I still use today. It’s a little bit temperamental and one of the filters has gone a bit, but it’s got an awesome power to it.

“The joy of this synth is that it can do a lot of stuff that other synths can’t. You can route the oscillator B frequency, which is your second oscillator, into the filter cutoff and make some crazy, super-fat sounds.

“I actually haven’t played the keyboard for ten years; it’s all done through this Kenton Pro Solo MIDI to CV converter. It goes from my computer to a blue Emagic box that converts it into MIDI, and then the MIDI cable goes to the Pro Solo, which converts it into a control voltage.”

Oxford Synthesiser Company OSCar

“Yeah, this is like the coolest synth on the whole planet, but unfortunately it’s incredibly temperamental. It’s called an OSCar. This is number 129; I think they made about 900 of them.

“It still works but I think there’s a ZX81 computer in there. Half of it’s a regular analogue synth with two filters in that you can mix together, but the other half has an old computer circuit board that does wavetable synthesis with 16 steps.

“It takes hours to make stuff but it’s highly unusual and there’s nothing else in the world like it. You can store sounds in it but they hardly ever come back. It’s the first time they tried to put a computer in a synthesizer. There’s a VST copy, but it bears no resemblance to the sound of it whatsoever.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.