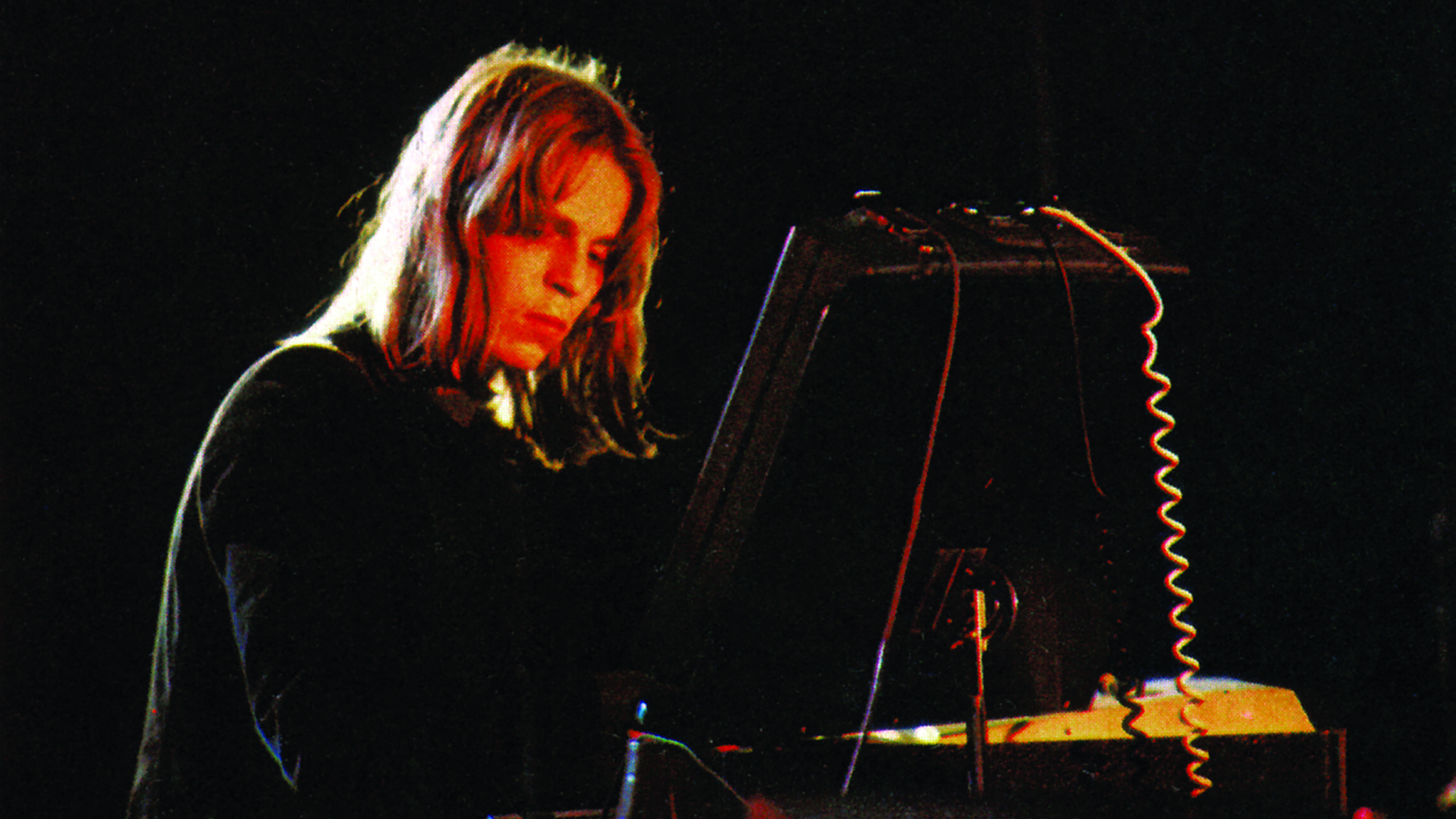

Tangerine Dream’s Peter Baumann: “There was no preparation. We just switched on the synths, smoked a joint and made some noise!”

The electronic pioneer on the making of the band's classic 'Virgin Years' albums

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Anyone who takes a serious look at the history of electronic music will, at some point, come across Tangerine Dream. Formed in 1967, they were one of the bands that undeniably helped steer music towards its experimental, electronic future.

In the late-’60s and early-’70s, there were several, shifting line-ups, but everything seemed to pivot around the band’s driving force and ‘frontman’, the late Edgar Froese. They enjoyed underground success with albums like Electronic Meditation (1970; recorded by Froese, Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler) and Atem (1973; this was the second album to feature what is widely regarded at the classic line-up of Froese, Christopher Franke and Peter Baumann), which John Peel made Album of the Year.

Their music also caught the attention of a young British hippy called Richard Branson, who’d recently set up his Virgin record label. Virgin had just signed Mike Oldfield and was about to enjoy worldwide success with his debut album, Tubular Bells. Tangerine Dream had found their spiritual home!

The deal with Virgin allowed them to make maximum impact on what was still a fledgling electronic music scene, and the period between 1973 and 1979 became known as TD’s ‘Virgin Years’. Remarkably, the band’s first album for Virgin, 1974’s Phaedra, made the UK Top 20, rubbing shoulders with the likes of The Carpenters and the Bay City Rollers!

It’s this era that has been chronicled and celebrated by the recently released and rather lavish 16 CD/2 Blu-Ray box set, In Search of Hades: The Virgin Recordings 1973-1979. Alongside remastered versions of the albums, there is a selection of unreleased Phaedra out-takes, some 5.1 mixes, a German documentary that hasn’t been available since it first went out in 1975 and several live shows, including Coventry Cathedral in 1975.

Tangerine Dream are still around. Sort of. It contains none of the original or Virgin Years members, of course – Edgar Froese was the only constant until he sadly passed away in 2015. The other two main members of the Virgin Years line-up were Christopher Franke (a member from 1971-87) and Peter Baumann (1971-77). Franke now works in the soundtrack industry in the US, while Baumann released several solo albums and founded the Private Music record label. Like Franke, he’s now based in the States and has just released a new collection of tracks called Neuland, recorded with another former TD member, Paul Haslinger.

We managed to track down Baumann to his San Francisco studio and asked him about the box set, playing live shows in cathedrals and the ‘relaxed’ recording sessions for Phaedra.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

According to the various versions of the Tangerine Dream story, it seems that you joined the band by accident. Is that actually how it happened?

“Yes, totally! A complete accident. I was at a concert and I ended up talking to this guy who turned out to be Christopher Franke. I told him that I was playing in a band, but I didn’t find the music exciting. It was a covers band… playing English and US rock covers. I told him that I wanted to find something that was more experimental. He seemed quite excited by this and made a note of my address. Several days later, I received a letter asking me to come to a rehearsal. His band was looking for a keyboard player.”

Analogue technology… A letter!

“Ha ha! This was decades before mobile phones. In fact, I didn’t even have a normal phone. None of us did. Musicians didn’t make much money back then!

“When I went along to see them, I was worried that they thought I was some kind of master keyboard player. I wasn’t! I grew up with classical music because my father was a composer and, yes, I understood classical music, but I wasn’t a fantastic classical musician.

“There was no need for me to worry. When I arrived at the studio, I said, “OK, what are we playing? What’s the song?” Edgar said, “I don’t know what we’re playing. We’ll start something and you can join in with us.” Christopher was brushing the cymbals very gently and Edgar started to create these long, eerie sounds with the guitar. At this point, synths were still an expensive luxury. The early songs were often created with guitars, organs, tape-loops and heavy use of effect boxes. I listened to the mood of the music and thought, ‘What do I play?’ That was kind of how Tangerine Dream evolved. It was all about the mood of the music.”

What was Edgar like to work with in the studio? What made him excited?

“Edgar did not get excited too often. Upset, yes! At the record company, the promoter and so on. In the studio and in general, he was very cool, calm and collected. It was very easy to work with Edgar. He didn’t complain much in the studio and was happy with most of what we created together. His mind was always drawn to the edge… the edge of science, beliefs, consciousness and the edge of music.”

Was the move towards a more electronic sound quite gradual?

“Suddenly, synths seemed to be… around. More people had them. In the beginning, it was baby steps. The first synth I ever saw was so basic: Just a box with one knob that switched from pink noise to white noise. And, I don’t think any of us really worried about how much synthesizers were going to change the musical landscape. We didn’t feel like revolutionaries. We were just kids playing music. Today, we’re using a guitar and Farfisa organ. Tomorrow, we’ll be using synthesizers. Fine. No problem. These new instruments were available, so we decided to use them.

“At first, there was no grand plan for Tangerine Dream, but the machine that really got things going for us was the EMS Synthi, which came from England. If you want to talk about a revolution, this was the point that it started. We began to understand what these new machines could offer us.

"That revolution seemed to be happening all over Germany. So much groundbreaking music appearing in what seems to be a relatively short period – UK journalists, with their usual sense of tact and discretion, called it Krautrock. There was Can, Faust, Klaus Schulze, Popol Vuh, Neu!, Amon Düül II and Kraftwerk, of course. Where did all this incredible music come from?

“Looking back, it’s easy to speculate, but I’m not sure if I can give you a definitive answer. Generally speaking, the German personality is not what you would call a rock ‘n’ roll personality. But there was a feeling in the air during the late-'60s. It was the zeitgeist… something that was happening all over the world. Paris, London and America. In Germany, it was very small. Berlin has always had an underground scene, but at that time, it was just a few artists who were trying to do something a bit more experimental. We wanted to make music that was different to the music our parents listened to. The synthesizer seemed to capture the new spirit. It wasn’t the blues. It wasn’t rock music. It wasn’t about playing these incredible solos. It was a new era.”

What else were you listening to at that time? Who were your musical influences?

“All of us were listening to what you might call classical electronic music. People like Stockhausen and Morton Subotnick. And some of the other hybrid bands, like Kraftwerk, Can, Agitation Free. Then, of course, Roxy Music, Pink Floyd and Bowie. But there were not too many ‘electronic’ acts at that time. The ones that we listened to most were Walter/Wendy Carlos, Ligeti and Conrad Schnitzler.”

How did Tangerine Dream work in the studio? When you first joined, the line-up was guitar, keyboards and drums. Did that mean you were able to record like a traditional band?

“Ha ha! Not at all. From day one, everything was improvised. Then, we would go back and maybe add some strange noises – this is before the synths. We would run around the studio looking for things we could hit or smash. We’d hit piano strings or scratch them. Anything that would give us a new sound.”

Early sampling?

“Exactly. Except that we didn’t have anywhere to store these ‘samples’. For a while, we started recording them on a two-track tape and, when we needed a particular sound, we’d find that bit of tape and press play. If we missed the cue, we had to do it again. Sometimes, we’d turn the tape over and play it backwards. It was all very random and quite chaotic. Compared with today’s DAWs, it was the prehistoric age!

“Actually getting us into the Manor Studio in Oxfordshire – where we recorded Phaedra – was a big job. A truck would gather our equipment in Berlin, then take the road and the ferry. It took maybe half a day to set up the equipment, but we never hurried. It was a very relaxed atmosphere… probably thanks to the hash!”

Once technology began to develop, you moved on to synths and early sequencers – did doing that add structure to the recording process?

“No! Even when we added sequencers, we used to play them live. The ones that we used allowed you to skip notes and steps as you went along, so they became another one of our live instruments.”

Was Phaedra improvised?

“Totally!”

Incredible! You had no idea of where the songs would go or what key they were going to be in? Nothing?

“There was no preparation. Nothing at all. We just switched on the synths, smoked a joint and made some noise. In fact, Phaedra specifically… I can remember we did that whole first section in one go. We worked on it afterwards, of course. We’d listen back and start treating different sections of the music. We used a lot of tape loops, plus the outboard gear, like phasers and flangers. Wah-wah pedals and different delays. Yes, a lot of work went into the album, but the original music was all improvised. Maybe one overdub, I think: The flute part.”

Were there times when somebody played a wrong note or something didn’t feel right? Did you ever stop and start the whole thing again?

“There was really never a ‘wrong’ note, just parts that didn’t fit as well. But that was not a reason to stop playing… as long as it didn’t throw the mood of the track. In the studio, we would keep recording and edit out anything that went against the grain.”

And when it came to live shows, was there ever any attempt at all to recreate what was on the album?

“Never. A live show for us was a chance to play some more music. As the concerts got bigger and we started doing proper tours, there were occasional themes and rhythms that reappeared, but nothing more than that. If we started playing and the music suddenly went off in this direction, we would follow it.”

What happened if one of the synths suddenly packed up? The EMS Synthi was not the most robust of touring instruments…

“That became part of the live show. It was live… things went wrong. And they went wrong quite a lot. Sometimes, they went really wrong. Sometimes, they went really right. Sometimes, the first part of the show would be fantastic, the middle bit was OK and the ending was lousy. We honestly never knew how it was going to turn out. But we were OK with that. It was exciting. There wasn’t much we could do about it, so we went on playing, hoping that an extra-cool part would overshadow the not-so-good part.”

What are the main synths and keyboards you remember from that 1970s period?

“The M400 Mellotron, the Fender Rhodes, the Moog 3P, the Synthi, the Elka Rhapsody… the ARP 2600. But, very early on, we started to go down our own path. We hired a company in Berlin and developed our own unique sequencers. Four units, all fitted into a big rig.”

One of the live concerts that’s included in the new box set is the Coventry Cathedral show in 1975. You had quite a thing for playing religious venues, didn’t you?

“Again, nothing was planned. We were asked to play a concert in a cathedral and we thought, ‘Yeah, that sounds like a great idea’. The acoustics weren’t always so good, but the atmosphere was incredible. A cathedral or a church is an excellent place to listen to music because you walk inside, and you immediately feel calm. You don’t want to jump up and down. Your awareness is expanded. That was perfect for listening to Tangerine Dream.”

You eventually left the band in 1977. Was it the usual ‘musical differences’?

“We put out some great albums and had some amazing success, but it began to feel like work. When we started, there were no rules. It was just about having fun and making music. Then it became a job. I wanted to try something different.”

There were some solo records, but you also set up a record label, Private Music, releasing albums from Philip Glass, your old mates in Tangerine Dream and Ringo Starr! There are also some brand-new releases from your Neuland project, which is you and another former TD name, Paul Haslinger. So what’s your studio setup today?

“It’s mainly Cubase. That’s all you need. There are good things about working with modern technology, but there are drawbacks, too. You can record a hundred different versions of the same melody on a hundred different instruments. Which one do you choose?”

With Tangerine Dream, the band had cutting-edge technology that only made a noise when it was instigated by a human. You’ve been there for the evolution of electronic music. So has technology changed what we all do?

“Well, that’s an ever-expanding question. Look back into history and you’ll see that the piano was once considered a tool of the Devil because it could play more than one note at a time. Edgar once told me a story about when he got his first fuzz box. He plugged in his guitar and the engineer working in the studio refused to record it. He told Edgar that distortion isn’t music.

“You could argue that there are more grey areas now. What is music? How much input should the technology have? But even when I’ve got all this technology at my disposal, the most important thing is the experience of the listener. The emotion they feel when they hear the music.”