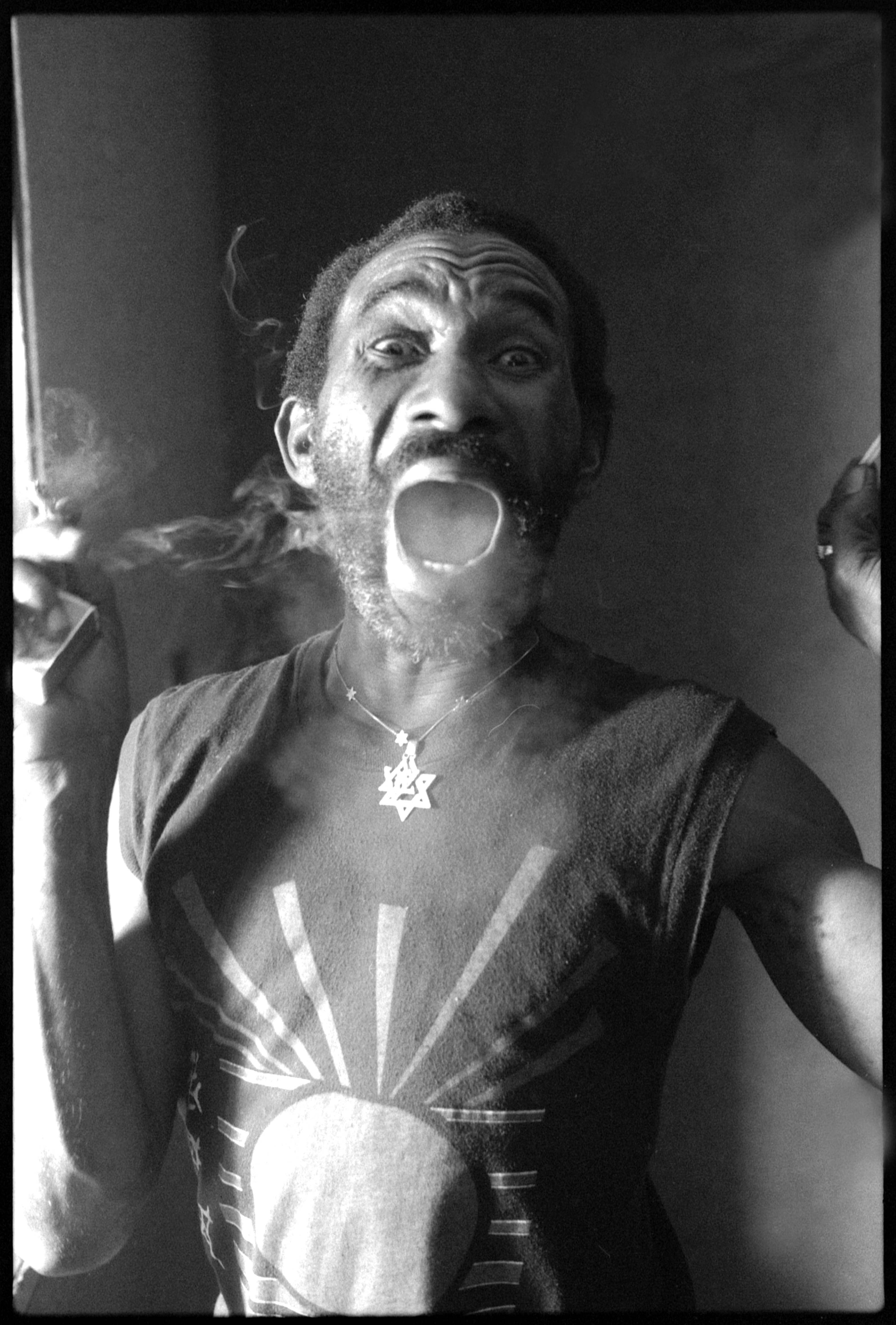

How Lee "Scratch" Perry's studio magic shaped popular music: “The studio must be like a living thing. The machine must be live and intelligent, then I put my mind into the machine and the machine perform reality”

We illuminate the genius of a visionary producer and artist that pioneered reggae, gave birth to dub, and paved the way for countless new sounds

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In our Pioneers series, we illuminate the genius of the most influential artists and producers in musical history. This month, we're focusing on Lee "Scratch" Perry, a producer, artist, and performer with a visionary approach to production that shaped the sound of modern music.

Music production is sometimes perceived as a largely technical exercise, a practice grounded in science and rationality. But for many of the most gifted producers, their relationship with the recording studio and its tools derives from a more enigmatic source; a place that the least cynical of us might describe as spiritual.

For Lee “Scratch” Perry, both the recording studio and the music-making process held such an elevated significance. “I see the studio must be like a living thing, a life itself,” Perry once said. “The machine must be live and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine and the machine perform reality.”

“I see the studio must be like a living thing, a life itself. The machine must be live and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine and the machine perform reality”

Perry’s visionary approach to music-making led him to become one of the most influential producers to operate on either side of the millennium. His work in roots reggae with Bob Marley, Junior Murvin, Delroy Wilson and Max Romeo propelled the genre onto the global stage, while his experiments in dub production boldly pioneered a sound and a methodology that has echoed through decades to inspire artists working in hip-hop, post-punk, dubstep and techno. Perry’s iconic dress sense, unpredictable behaviour and his lofty, often mystical way with words combined to create a proudly eccentric character that singled him out as a true original.

Born in ‘30s Jamaica, Perry’s entrance into the music industry came with an apprenticeship at Studio One, a renowned record label and studio run by Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, working as a talent scout, songwriter, drummer and vocalist. It was here that Perry began to experiment with recording his own music, penning “Chicken Scratch”, the debut release that would earn him his nickname.

As the ‘60s progressed, Perry style would evolve from ska and rocksteady into the nascent sound of reggae, as evidenced in his 1968 hit “People Funny Boy”. Featuring a sample of a wailing baby that was intended to taunt a former collaborator, the track was, in typical Perry fashion, miles ahead of its time.

Blessing his equipment with mystical spells, burying tapes in the ground outside of his studio, and even spraying them with blood, urine and whiskey, he sought to infuse the music with a supernatural quality

After leaving Studio One, Perry set up shop on his own, assembling an ensemble named The Upsetters to record solo instrumental tracks like “Return of Django” that would hit the charts in the UK, before the band linked up with Bob Marley to record, under Perry’s direction, some of the best-loved songs in Marley and The Wailers’ catalogue.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

These formative experiences compelled Perry to set up his own studio in 1974 and take complete creative control of his work; located at his home in Kingston, the Black Ark studio became the stage for Perry’s early adventures into sonic experimentation.

It was here that Perry began to explore extraordinary production techniques that verged on lunacy. Blessing his equipment with mystical spells, burying tapes in the ground outside of his studio, and even spraying them with blood, urine and whiskey, he sought to infuse the music with a supernatural quality. Whatever you make of his techniques, Perry was clearly on to something - the music he recorded here at Black Ark became some of the most enduring in reggae’s history.

Much of Perry’s genius was in his commitment to spontaneity. “I'm a miracle man - things happen which I don't plan, I've never planned anything,” he says of his process. “Whatsoever I do, I want it to be an instant action object, instant reaction subject. Instant input, instant output.”

Dub production techniques like the ones pioneered by Perry effectively turn the mixing process into a live performance happening in real time, adjusting faders, muting tracks and running musical elements through sends, out to effects like echo and reverb and back on themselves or into different effects to create wild soundscapes and clouds of feedback.

Armed with a relatively basic set-up consisting of a TEAC four-track tape machine, Soundcraft mixing board, an Echoplex delay unit and a Mu-Tron phaser, Perry became one of the first producers to understand the potential of studio gear as an instrument in its own right.

As the ‘70s drew to a close, Perry’s mental health declined, and he eventually set fire to Black Ark. Burning the studio to the ground in a fit of rage, he was incensed by the intrusion of “unclean spirits” and disreputable characters into his sacred creative space.

The years that followed saw Perry move to London and then Switzerland, where he would return to good health and go on to cement his reputation as an innovative producer, performer and solo artist, as the ideas he pioneered in Jamaica continued to spread across the globe.

Perry remained prolific as decades passed, releasing dozens of solo albums and producing hundreds more, winning a Grammy Award and collaborating with everyone from The Beastie Boys and The Orb to Paul McCartney and Keith Richards, who described him as the “Salvador Dalí of music”, saying that “the world is his instrument - you just have to listen.”

In 2021, Perry passed away and left a monumental legacy behind, but there is no doubt that the world will keep listening.

Lee "Scratch" Perry in five tracks

1. Lee “Scratch” Perry - People Funny Boy (1968)

Perry’s debut single was written to disparage Joe Gibbs, a fellow producer and head of Amalgamated Records. After the pair fell out over a financial dispute, Perry took aim at Gibbs in the best way he knew how, mocking his former employer with the inclusion of a well-placed sample of a crying baby over a lilting proto-reggae beat. While not the first reggae song ever written, it’s thought to be one of them, and perhaps also one of the first examples of a diss track.

2. Lee “Scratch” Perry & The Upsetters - Black Panta (1973)

This landmark recording is from Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle, widely considered to be one of the first dub records ever released. All of the genre’s hallmarks are here; a cavernous sonic atmosphere and creative use of effects, with bass and drums placed firmly front and centre in the mix. A dub classic, it shows Perry pushing the boundaries of his equipment and reimagining the role of the producer in the process.

3. Junior Murvin - Police & Thieves (1977)

Police and Thieves is one of the so-called “holy trinity” of albums recorded under Perry’s direction at Black Ark Studios, alongside Max Romeo’s War Ina Babylon and The Heptones’ Party Time. Its title track is a politically charged anthem that speaks of the conflict between Kingston’s street gangs and brutal law enforcement; the undercurrent of darkness in Murvin’s heartfelt croon is accented by Perry’s expansive, masterful production.

4. Lee “Scratch” Perry & Mad Professor – I’m Not a Human Being (1995)

Perry first teamed up with Neil “Mad Professor” Fraser in the ‘80s, but one of the most memorable products of their collaboration is the 1995 cut Super Ape Inna Jungle. Foregrounding Perry’s inimitable vocals over sliced and time-stretched breaks, the track is a reminder that his superhuman influence stretched far beyond reggae into the wider worlds of electronic and dance music.

5. Lee "Scratch" Perry & Daniel Boyle - War Dub (2015)

In 2015, producer and reggae fanatic Daniel Boyle reached out to Perry with a brilliant idea: carefully reassembling the original array of studio equipment from his Black Ark studio to write and produce a new collaborative project. The results were predictably fantastic (and Grammy-nominated), thanks in large part to Boyle's commitment to recreating Perry's set-up and techniques; in War Dub, the '60s Grampian spring reverb and Roland RE201 Space Echo lend the music an authentic dub feel.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.