Kingdom: “I’m definitely anti gear lust; all of my favourite music was made with cheap hardware or FruityLoops"

Ezra Rubin has worked with some of the most-talked about artists of the last five years, but he may have saved some of the choicest creative chunks for his own acclaimed work…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Kingdom, Ezra Rubin has shown that visionary ideas can still have a place within the contemporary mainstream – it just takes his peers a few years to catch up. Equally informed by the elastic production work of studio lifer Timbaland and the Providence, Rhode Island noise scene, Rubin started Kingdom using rudimentary Boss drum machines and an early copy of Reason.

But his attention to detail in the carefully constructed sonics of Kingdom tracks shows that Rubin’s skills as a producer have grown by leaps and bounds since those earlier days, and his tracks over the past decade have soundtracked everything from club nights to runway stages, and everything in between.

In his own work, as well as running the cutting edge LA label Fade to Mind, Rubin’s dedication to a certain aesthetic remains pretty airtight. Just look at the visuals for Fade to Mind’s releases and you’ll see that they each capture a feeling and spirit of freedom, much like the euphoria and rush of a great, memorable night packed between two speakers.

Article continues belowThough much of his work remains behind the scenes, Kingdom’s past collaborations with Kelela, SZA, and Syd from the Internet show that he’s also able to steer the ship when he’s working with others.

This September saw Kingdom returning with a new full-length album entitled Neurofire that finds the producer exploring headier sonics matched with slightly faster tempos. This time, he’s also chosen to feature less known voices, working with friends and newcomers.

We sat down with Rubin to discuss his early mash-up attempts, learning from Bok Bok, and what it’s like to run a label that the LA Times has listed among “the most influential projects in LA underground music.”

So you are originally from Massachusetts but you went to school in New York City, right?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Yeah, I grew up 30 minutes west of Boston, near to Natick. I then moved to New York when I was 18 years old. I stayed there for ten years, then headed west to Los Angeles.”

What attracted you to LA?

“I had been touring a whole bunch and visiting LA a few times a year for shows and just to hang with my friends. I was DJing at Mustache Mondays and other shows, hanging out and playing around with music with Total Freedom and Nguzunguzu. I liked the atmosphere and the weather and proximity to nature and a slightly more open and experimental music scene.”

We read that your entrance into music making in the Kingdom world was through making edits and through putting acapellas over UK garage instrumentals and such. What were you making musically before that, if anything at all? What would you say was your first real musical obsession?

“Yeah I was always making music. I was always fascinated with drums, and always wondered how electronic drum sounds were made when I heard them on the radio in the ’80s.

"My dad bought me a cheap Kawai keyboard when I was seven, and I used that thing every day. I never really got proficient at reading music but always messed around and definitely mastered playing drumbeats on the keyboard

"I also had a brief stint taking piano lessons when I was eleven, just for a year. My teacher was really into early MIDI software and had a Korg M1. She could tell that I was never going to practice or really sightread so she would show me stuff on the computer instead.”

Wow. That is incredible foresight!

“Yeah, it definitely planted the seed early on. But then I never saw another piece of music software again until like 2004, so like 10 years later!

"In the gap in between that, my brother dragged me into some ska and punk bands. I also had a four-track recorder that I played around with on the side, playing keyboard and drum parts into it one by one, making my own tapes.”

What sort of music was influencing you around this time?

“This was 1997-1999, so Darkchild, Timbaland and the Neptunes were most of the sounds you heard on the radio. When I heard them I was obsessed - hearing pop become so polyrhythmic and stutter. I would try to imitate the beats. By then I had a Roland Dr. Groove (DR-202) and Dr. Sample (SP-202). The DR-202 was a super cheap, all-in-one machine. It had 808s, 909s, 606s, and a few other basic kits, and around ten bass sounds.”

So, what led you to the DR-202 and the Dr. Sample? How did you know to get them? Was your brother a part of that decision too?

“All of the options were connected to speakers at Guitar Center, so I just went in and found them. In my mind, I was already into synth drums and basses, so the Dr. Groove made sense because it had it all. It also marketed itself with genre names, like trip-hop and drum & bass and lo-fi etc, which made sense to my brain at the time.”

So you were into electronic sounds from an early age? It doesn’t seem that common around Boston. Do you remember having to seek out those sounds? Jungle wasn’t a thing on the radio really, I don’t think.

“Yeah, probably not. My brother turned me onto a lot of it. But there was a small scene. There was a college radio show called No Commercial Potential that played lots of ambient stuff. Also DJ Rupture’s Toneburst collective was Boston-based and had a big influence on me. There were definitely jungle parties happening but I was too young to go.”

And then you moved to New York to go to Parsons, correct?

“Yes, I was pursuing fashion design at that time. One thing to note is that I got really sick the first year in NY and had to go home and get my tonsils out. Those days in bed on codeine cough syrup was the first time I got really productive and really learned my way around the Dr. Groove and syncing it with the Dr. Sample.

“Around this time, I also had a little band with some friends. That band was Dr. Groove, Dr. Sample, four vocalists and lots of fog! Our final CD-R, which we printed up in 2004, was the first time I recorded the stems out from the Dr. Groove and Sample into Pro Tools on my brother’s computer. We had a song called Kingdom, which is actually where the name came from.

"Shortly after, in 2005, I got a Pro Tools interface and made my first Kingdom tracks. I was still (making music) casually as a hobby, as I working at an art gallery full time.”

What were those first, early Kingdom tracks made with?

“They were half Dr. Groove, half Reason. Each track had elements recorded in from the drum machine, as well as stuff from Reason over the top. Since I sort of knew the DAW from using Pro Tools, I would also drag in samples and chop audio a little bit.”

So what did those early songs sound like? Did any of those first Kingdom songs see release?

“They were just a CD-R. I guess I’ve always been multi-genre, as some of them had a mystical synth industrial vibe, some were weird takes on trance, and some were lo-fi dancehall.

"I was into Providence noise stuff at the time, like Lightning Bolt, but also New York was feeding me a lot of new influences. Back then people still sold bootleg CDs in the subway! I bought a lot of amazing reggaeton remix CDs and dancehall instrumentals. New York in general still had some rawness and secrets. It was a good time to be there.”

Did DJing enter your life when you first got to New York?

“Around 2005, my friend Kevin had the idea of throwing a party. None of us knew how to DJ. We threw it in the back room at a liquor store and just played CDs we burned - no live DJs. But somehow it caught on a bit, more people started to come – Telfar, the DIS Magazine crew, and some people from Hood By Air. I met them there and Telfar asked me to DJ his night at a real club. But at the time I really had no idea how to DJ. I burned two CD and he showed me at my first gig – on a pair of horrible rackmounted Denon CD players!”

Let’s fast forward into the present. Where is your studio these days? What’s your routine for working or getting into the studio? Do you try to get in there on any regular schedule?

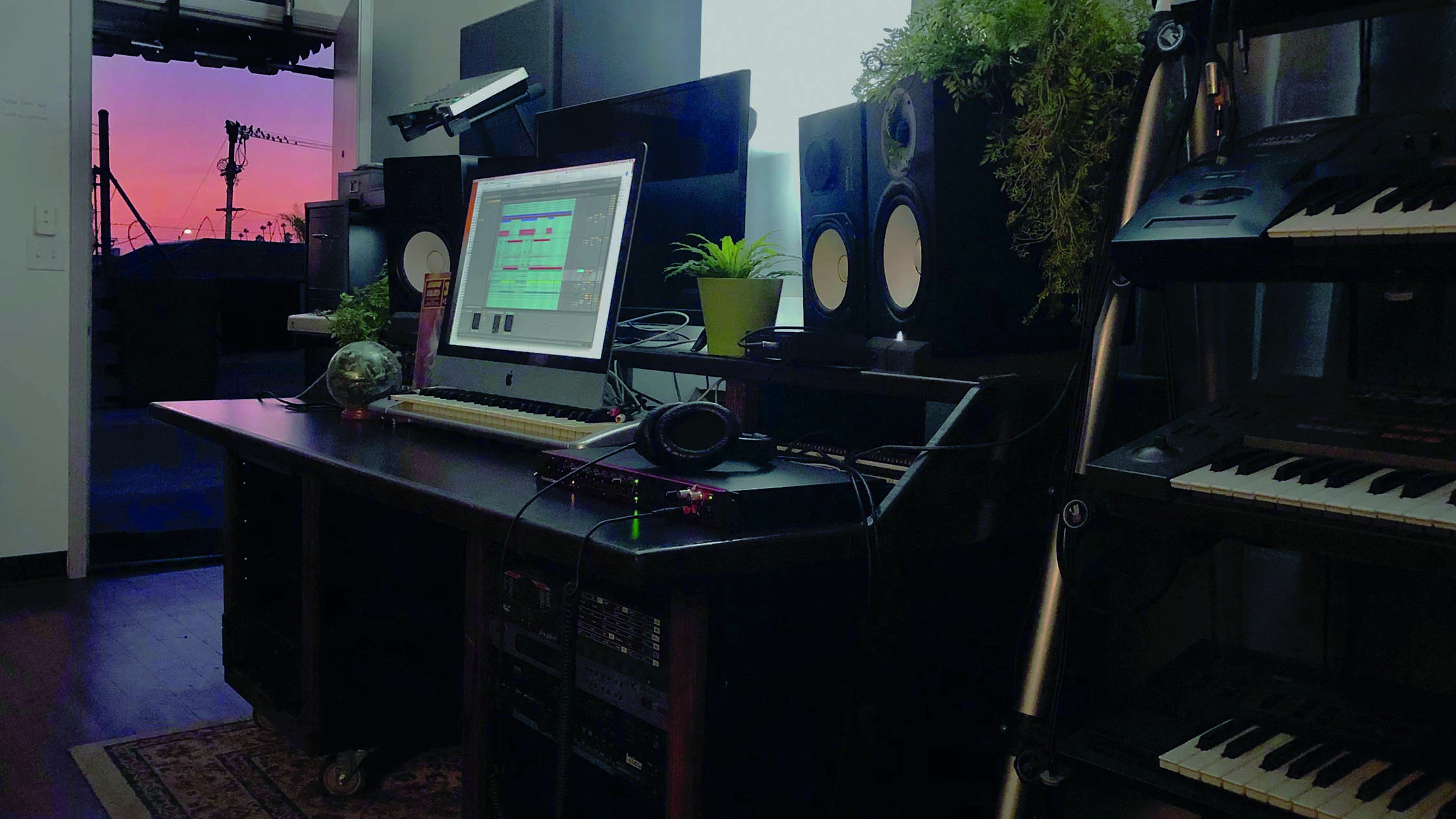

“My studio is in the Koreatown area of Los Angeles. I managed to find a small private spot where I can be loud at all hours. I try to break it up more these days and get in earlier, but most of the time I’m pretty into my routine, which is to hike or be outside all afternoon, then work at the studio from 4pm to 1am. No matter how hard I try I get a burst of motivation at 11pm!”

Do you find yourself working on music all the time or do you focus on it more when there is a specific release you are working on? Are you sort of always compiling ideas?

“I do almost everything myself so I’m switching between design, admin stuff, and making music. It’s gotten design and admin-heavy leading up to this album, really for the last six months, but before that I was in a really creative space, making music every day to create the pool of demos that would go towards Neurofire.”

How do you feel Neurofire is different from Tears in the Club or your other previous releases? Was there a certain thing you wanted it to capture?

“There was something dreamy and atmospheric about Tears in the Club. The new album is all about showcasing new talent, and a rare chance to hear pop and R&B vocals over faster and more experimental beats. With Neurofire I was ready to capture a little more tension and turbulence in my music, and go back to the chopped and remixed vocals instead of traditional vocals. At times it is a bit more distorted and more uptempo, while still blending in those emotional moments.”

Looking over the gear list you used for Neurofire, we noticed it’s pretty equally split between hardware and software. You do have a few hardware synths in there, most notably the Korg Triton. Was the Triton something Bok Bok introduced you to or did you know about it from Timbaland or the Neptunes? They are pretty well-known Triton users.

“I knew it was Lil Jon’s favourite as well as the Neptunes’. Also, doing some research online, it’s described as the bigger better M1, so it was a logical choice for me. Also a lot of early grime sounds came from it.

"My last two projects, Tears in the Club and Vertical XL, had a lot of Triton on them. There were lots of melody stems I just played freestyle and quantised after, or I played the drums live on the Triton and then chopped and looped the audio. Neurofire has a little less of that. I also used Omnisphere and samples of my Korg DS-8 and Yamaha T81Z rack.”

How do you choose which of these sound sources to turn to?

“I feel like I finally have a sense of what each of my keyboards and VSTs has. So if M1 doesn’t have it then I will try to imagine if my hardware has it. I do check out Omnisphere quite often, though. There’s still plenty of M1 on the new album, too, but with more effects to help disguise the overly clean feel that it has.”

Did you mix this album yourself? If so, can you tell us a bit about that process. Was the Waves RVox plugin a big part of the mixing process? Similarly, what about Decimort do you like as opposed to other distortion or bit crushing plugins?

“I recorded and mixed the entire project, give or take two or three stems. I have a fantasy of finding someone else to do it for me one day because I really go into a lot of detail when I’m mixing. It takes months and months.

"Mixing the instrumentals is a lot about what should be wide or narrow in the stereo field. If the ambience of the track has some grit or distortion to it, sometimes it’s about adding it to the overly clean tracks so that it sounds more like it’s come from the same world, sometimes with the help of D16’s Decimort, Ableton’s Saturator, or Ableton Erosion.”

What’s your advice on mastering the low end?

“Getting the bass right takes a lot of time. Some of my tracks have a tight kick, a sub bass, and a synth bassline, and they can’t all fire at once, so it’s tons of automations and sidechains. Sometimes even automating EQs so the bass sounds get out of the way of each other at the right moments.”

And how do you approach vocals? Do you have certain chains that you rely on now?

“With vocals it’s a ton of surgery, too. Bok taught me a lot early on with instrumentals, but I’m entirely self-taught on vocal mixing. Just guess and check and listen.

"My first vocal mixes I relied almost entirely on volume automation to make the vocal sound even. I’ve finally started to grasp compression more. (Waves) Rvox is the simplest vocal compressor I’ve ever used. It seems to even out the volume without affecting the overall vibe of the vocal - I just started using that this year.”

“Creating new music feels more rewarding right now but I know the raves will be back”

I noticed that you’re using a relatively inexpensive vocal mic, even though all the vocals on Neurofire sound super crisp and detailed. What are your thoughts on gear lust and pining after the latest thing?

“I’m definitely anti-gear lust. All of my favourite music was made with cheap hardware, or Fruity Loops. I tried to buy a highly recommended high-end mic right before making the album; I really didn’t like the sound at all.

"The MXL V67 is under $100 and delivers good quality. I’ve been using that mic my entire career. My first one was a used one that finally died after 10 years of use. So I bought a new one of the same.

"I love to experiment with vocal effects, so if I’m going to do that anyways, I may as well get a clean, predictable signal at the start. I think I’m used to it, too; you have to apply different effects to a signal from a different mic. The 'air' effect on the Scarlett [audio interface] helps, too.”

I was just about to ask about your interface and your monitors as well. What do you currently have in your studio?

“I’m using a Focusrite Clarett 8Pre with Yamaha HS8s, with the sub, although my friend has a big pair of Adams and I think I like those better.”

What is the room like that you’ve been working in? Is it treated? How long have you been in this space?

“I’ve been in here for four years, I think. I have six acoustic panels and three bass traps, though I think it needs some more. I like the way that it sounded when I was facing the shortest wall, but facing the long wall also makes the space a lot more enjoyable for guest vocalists.”

Let’s talk about the guest vocalists a bit, as this new album has even more collaborators and vocalists than your previous work. How do you choose vocalists who you’d like to collaborate with? At what stage in the process do you think about vocals? Do you try out multiple vocalists on a single track and see what works?

“My last album has SZA and Syd on it. That was my first attempt at working with bigger vocalists. This time around I just wanted to work with friends, and go deeper into collaboration. I love working with female vocalists, or male vocalists who are in touch with their vulnerability. I still can’t get over the feeling of hearing a falsetto vocal.

“With this album I wanted to move away a little from the standard vocal performance, and make it sound more remixed and sampled. Most of them have unusual chopping, layering or effects. It happens organically; the tracks that have more space may need vocals.”

I’m curious as to how you see your relationship to the LA club scene and how you think it’s evolved over the years. Do you feel like you’ve settled into a bit of a community in LA now that you’ve been here for a bit? Do you see Fade to Mind as an ‘LA’ label?

“The first years were really amazing. I don’t think people here had really heard the mix of sounds that we were playing. I think our warehouse parties with Venus X and Manara really opened people’s eyes in LA terms.

“It’s been harder lately, as Nacho Nava, creator of Mustache Mondays, passed away last year. He was holding the scene together in a way. There are also just some harsh realities, financial and otherwise, that make throwing parties really challenging. Creating new music feels more rewarding right now but I know the raves will be back.

“Fade is an LA label, but not what people from other places might otherwise associate with LA. It comes from the secret corners, and is very influenced by our global community. I think the overall music scene has dispersed a lot. I don’t think it’s a bad thing though, as people are exploring a lot of uncharted avenues.

“Fade to Mind has always been a really diverse place, inclusive since day one. Our parties have always had an amazing mix of gay and straight people and people of all ethnicities, something that was rare in 2011.”

Kingdom's latest album, Neurofire, is available now.