How to become a session bassist: top tips from Leland Sklar, Sandy Beales and more

Advice from bass players at the top of the game

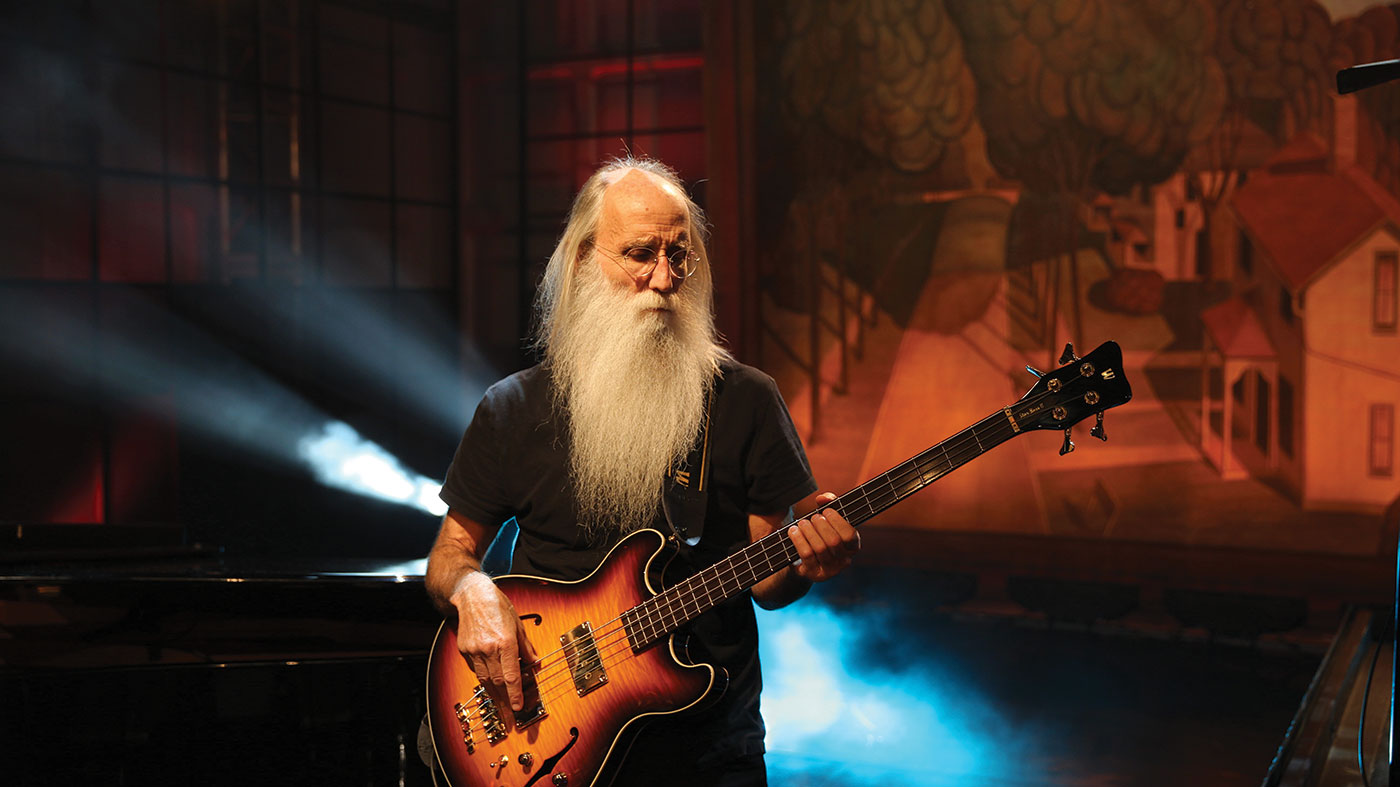

Lee Sklar

You’ve recorded thousands of sessions, Lee. Do you ever listen back to the stuff you’ve done?

“The best time is when you hear something that you recorded as a basic track and you never heard as a finished song. I’ll be in a supermarket and hear a song and think, ‘That’s really cool’ and then you sit for a second and you think ‘Wait a second, I know that tune!’ and it was you.”

What is your best-known session?

Whatever sound and style I’ve created for myself over the years, it seems to fit with a lot of genres

“Probably one of the songs I played with James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt or Jackson Browne. Barbra Streisand is still going strong: I played on some of her early stuff too. All the studio guys I know ask me to play something off [epoch-shaping 1973 album] Spectrum with Billy Cobham. Plus I’ve done hundreds of country records with people like Reba McEntire.

“I’m really proud of those things, but I’m also really proud of having played on ‘It’s Raining Men’ by the Weather Girls and ‘I Am Woman’ by Helen Reddy. That’s the sign of a working musician: it’s not just about the big, attention-getting hits.”

How picky are you about the songs you’re asked to play on?

“I play what I’m called to go play. It doesn’t matter if I’m working with Il Divo or Veronique Sanson. I’ve even been called in to put bass on hip-hop projects, and it’s not one of my favourite genres, but I’ve worked on some cool stuff within that genre.

“I’m really open: I’m not one of those people who shuts anything out. Whatever sound and style I’ve created for myself over the years, it seems to fit with a lot of genres. It’s not like being a one-trick pony who gets called to do one thing, and you get called to do something else and you’re really out of your league.”

Do you ever find a session too technically challenging?

“There have been times where I’ve been called to play on things that I think another bassist would be better at, so I suggest that person instead. I remember when John Patitucci lived in LA, I’d say to people, ‘Call John. He’s the guy for this’. I like to share, I’m not possessive about things. It’s about whatever’s best for the project.

“For example, I’m not a good slapper at all, and I don’t play with a pick. I remember Quincy Jones called me to play with him and he said, ‘You do play with a pick, don’t you?’ and I said no, so we decided we weren’t going to work together, because on the stuff he was doing at the time he really wanted a pick player. I can bullshit my way through it: I keep one of my fingernails long so I can play like that - but my facility isn’t there, probably out of laziness.

“As for slapping, I’ve had a lot of wrist injuries over the years and I don’t have a lot of dexterity with it. Once again, I have friends who live and breathe that bass style, so I recommend them when slap is needed.”

Nick Beggs

“That’s the thing about it - it’s big, it’s ungainly and if you put it in the wrong hole it can really hurt!”

Don’t flinch, readers: it’s just Nick Beggs, bass-playing chameleon and session ace, describing why he can’t use his Chapman Stick on every session that comes his way.

“I’d play it all the time if I could fit it into everything,” he says. “Tony Levin seems to be able to make it work in a lot of places but even he doesn’t put it on everything.”

People might not know what they want, so if I can help them to reach that point, that makes life easier

Session bassists, take note: theory can help. After his ear- (and eye-) catching performances with Kajagoogoo in the early to mid-80s, Nick’s bass playing talents were in much demand, although he had to take himself back to college to gain the theory he needed.

“I didn’t know the difference between major and minor scales,” he tells us. “Everything I did in Kajagoogoo was just based on my ear: I couldn’t read music or note anything down, I cut my teeth on prog-rock but I came at it from a guttural response, so I went to Basstech in Acton in 1987 and studied with Rob Burns and Terry Gregory who both taught me to read music. I was reapplying it as I was learning it, because it was time for me to stop being an artist and time to become a musician.”

Homebody

Alongside his current work with Steven Wilson, the Mute Gods and Steve Hackett, Nick is constantly approached to add his deft skills to sessions: he carefully selects which projects he can actually contribute to.

“I don’t like recording studios, because I don’t believe I deliver my best stuff in them,” he says. “I record at home on my own, with enough time to get the sound how I want it, and enough time to learn the piece of music without any pressure. I know how to get the best out of my instruments: what I use depends on the track.”

Every session is a different experience, and Nick approaches each one with an open mind.

“Sometimes it’s a question of educating people,” he explains. “I’ve always had ideas about how something should sound sonically. People might not know what they want, so if I can help them to reach that point, that makes life easier.”

With so much experience behind him, Nick has the following words of advice for anyone wanting to approach the murky world of sessions.

“There’s two approaches: commerce and artistry. You can look at it as making a living, and being the everyman guy who covers all the bases - but then, do you really sound like you? Are you being asked to sound like a well-known bassist, or are you being asked to sound like you? I’ve had to do both. It’s also important to be able to spot and identify your own shortcomings, because you can’t please everybody. Big names have gone into sessions and not been able to please the artist or the producer, and you have to accept that that might be a possibility - but every day you get paid is a good day.”

The Mute Gods’ new album …Tardigrades Will Inherit The Earth is out now on InsideOut Music.

Mo Foster

If you get asked to do a session, what preparation do you need to put in?

“First of all, you’ve got to do your homework. Play live with a lot of other people. If you’re a studio player, you’re going to be called upon to play in any imaginable style, and do it very well, so unless you’ve done several years slogging around, you’ll have problems.

Nowadays it’s a world of barter: for example, I did some bass parts for a guy who taught me how to use Logic Audio

“You’ll need to play music that you don’t like, and be good at it. As well as coming up with ideas, you have to have great time. It’s hopeless if one of you is racing or behind the beat. When everyone is together it starts to feel strangely effortless: there’s no struggle. And you have to be comfortable with a click-track.”

What other skills do you need?

“A good session player has a nice supply of jokes, because being in the studio is a social thing. You need to enter a zen-like state of meditation when the red light goes on, and focus on the bass part, and then the light goes off and you start laughing again. The two states are vital because they let off steam for the other.”

How much did you get paid per session when you started out?

“In the 1970s, the Musicians’ Union rate was £9 for a three-hour session when I started. Later it went up to £12! That may not sound like much, but it was 10 times more than I was earning as a touring musician - I remember earning £20 per week on the road. You could get extra money on a session by doubling, in other words playing a second instrument or track, or porterage, which was a fee for transporting your gear.

“In the 80s, you could ask for double scale if you were really good. Sometimes you just thought of a number. I remember being asked to go to a Japanese studio to record an album, and when they asked me what I charged per day, I just made up a number. They said yes, and I thought ‘Damn! I should have asked for more!’ Nowadays it’s a world of barter: for example, I did some bass parts for a guy who taught me how to use Logic Audio. That goes on a lot.”

Sandy Beales

Seize your opportunities

Okay, let’s begin; top tip, day one, book one, page one, is saying ‘Yes!’ to every opportunity. Throw yourself into everything: gigs, recording, jam nights, attending masterclasses, practice.

Anything that means you’re picking up and playing your bass is a positive thing. Sure, this sounds simple, but you never know where the most random connection may lead: perhaps it’ll bring you the most amazing opportunity.

Become a chameleon

Anything that means you’re playing your bass is a positive thing. You never know where the most random connection may lead

The story above also ties in nicely to another important tip: be multiskilled. Get your synth bass playing to a good standard; make yourself comfortable on a fretless; venture into upright playing.

This way you have more strings (literally) to your bow, and no matter what is called for on a session or a gig, you’re ready to go, with all the tools and skills you need. If an MD wants a certain sound and you can provide it quickly and with minimal hassle, everyone is going to be happy. Trust me on that.

Remember your etiquette with fellow musicians

Be kind to people and good things will happen. Your connections are key. Get tight with drummers, as a strong rhythm section is a valuable commodity. Treat your bass tech and the rest of the crew with respect when you tour.

It’s important to remember that by the time you walk on stage, other people have already been working for hours getting the production and your gear ready. They’re your safety net, so being friendly and having a positive relationship with them gives you security and comfort on stage.

Master technique

I can’t stress enough how important timing, feel and the understanding of various musical genres is. Expand your knowledge of musical genres and the techniques involved to create an authentic sound for those genres, such as palm muting or pick playing.

You will become versatile and a useful commodity if you can adapt your technique and your sound to any genre. This is especially important during recording sessions. If your playing complements the song and fi ts the genre, you’ll earn your session fee.

Excerpted from Sandy’s much longer sessions feature in The Musician’s Handbook: Bass Guitar, out now.

Pete Thoms

Most employment out there for bass players is in film scores, game music and library music sessions. There aren’t so many record sessions anymore, even though they used to be the bread and butter of the job, along with jingles.

Reading music is an advantage. Not everybody who records sessions is a sight-reader, but it’ll be to your advantage if you can read something pretty much at sight. The top bass players - the Andy Pasks and Steve Pearces of this world, who get a lot of that sort of work - sight-read, and also play double bass. That takes their employability to a different level. You also need to be able to make something up on the spot if someone hands you the chords.

Show an interest in what you’re doing: a lot of session players get criticised for turning up and being blasé

There’s a whole spectrum of circumstances where that applies, from being given a note-for-note chart to being sent an audio file with no bass part and being asked to contribute one. If you can only do one of those things, it’ll limit you when it comes to working. If you say ‘I only play heavy metal’ then there’ll be fewer opportunities than if you play in multiple genres.

Be flexible - you don’t know what you’ll be asked to do. You may be asked to play like Ray Brown or Larry Graham or Flea on different sessions. People will expect you to cover as much territory as possible, so limit that flexibility and you’ll limit your employability.

Turn up on time, with the right equipment. Have a good sound and intonation if you’re playing fretless or double bass. Show an interest in what you’re doing: a lot of session players get criticised for turning up and being blasé. The best session players are those who are motivated. For a new artist the music they’re recording is everything to them - you need to show some desire to make their music the best it can be.

Most recording studios are in London, with some in big cities like Manchester and Liverpool, but there are now a plethora of online opportunities. You can play for anyone in the world with a good online presence. A lot of UK session musicians sign up to American session agencies: that’s a good way to get into it, although it’s no longer enough to send a CV and a Soundcloud sample to a producer and say ‘employ me’.

Make your playing known to a fixer and as many musicians as possible. You can then start to build a reputation for reliability, flexibility and skill. We have agreements with the record labels, as well as the BBC and the other TV companies, which lay out certain minimum rates - and musicians and producers should abide by those and not undercut them.

The minimum record session is £120 for three hours, although indemand players will often charge more than that. The main thing is to sign the MU documentation when you get a session, because that’s vital: there’s nothing worse than doing a session and finding out later that you have no paperwork to support the fact that you played on a track.