Guy Pratt: “The '80s music business was this ludicrous theme park awash with money. All you had to do was get over the fence”

We talk to the Pink Floyd, Madonna and Michael Jackson bass legend

Guy Pratt is a hero in our world.

If we were to run through his career in a couple of sentences, we’d say something like ‘Played with Icehouse, Bryan Ferry, Pink Floyd and David Gilmour; recorded world-famous bass parts with Madonna and Michael Jackson; wrote, produced and played on loads of hits; now has a popular comedy act’.

He’s a bon viveur and intellectual - although he still insists that he’s basically a punk kid who got lucky

But there’s much more than that to Mr Pratt. He’s a bon viveur and intellectual - although he still insists that he’s basically a punk kid who got lucky - with a feast of stories to tell thanks to a career at the deep end of the bottom-end.

Some of these stories are printable in a family publication such as this and many others most definitely are not. He’s seen things most of us wouldn’t dream of, and recounted many of the more wholesome anecdotes in a 2007 autobiography, My Bass And Other Animals.

An interview with Pratt is not like an interview with other people. When we meet up in a snooty restaurant in Brighton, our man is on feisty form, just how we like him. He’s riding high on the news that his new band, Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets, will be touring the UK and Europe [the tour took place in September - Ed].

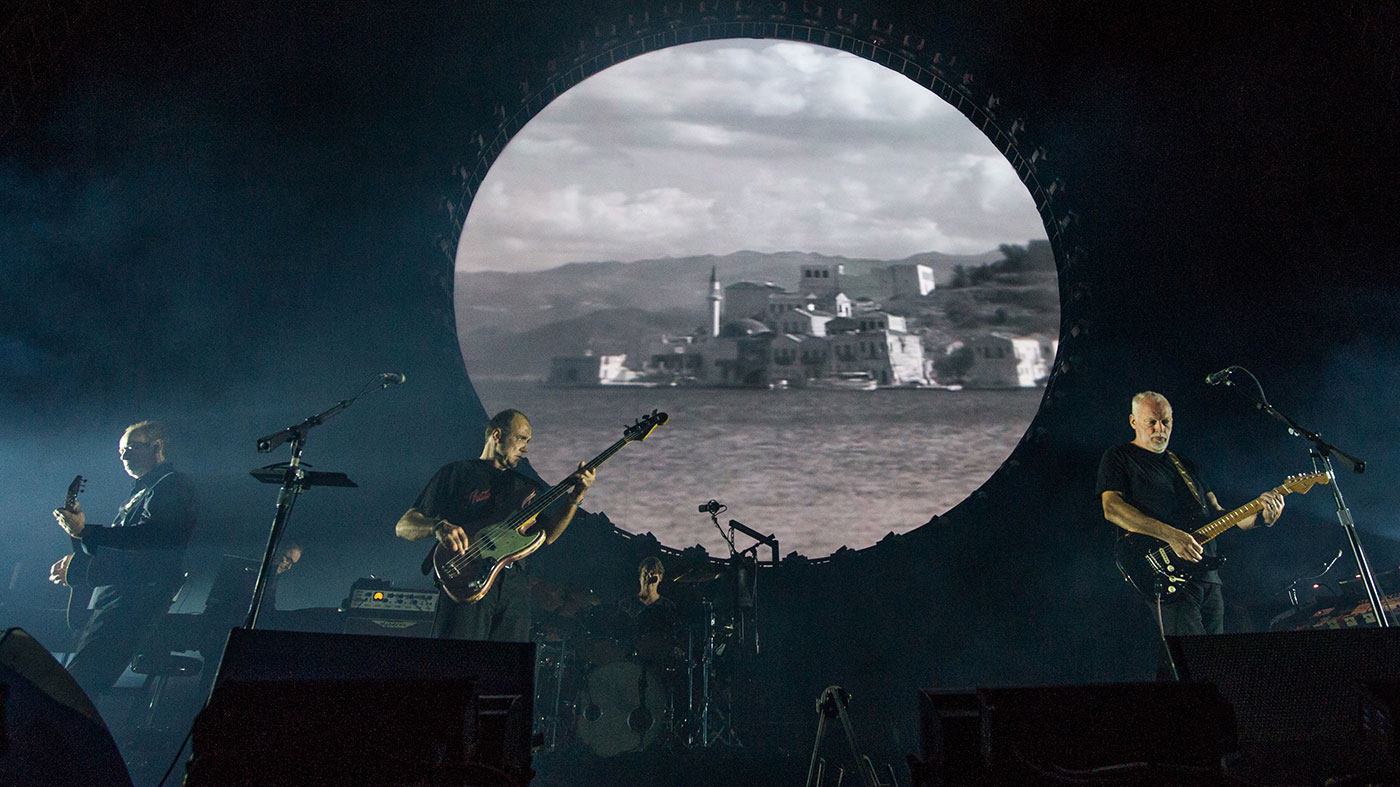

The group, led by Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason and also featuring Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet, guitarist Lee Harris and keyboard player Dom Beken, played a string of warmup shows in May - and received glowing reviews right across the media.

We were at one of those gigs, and can confirm that the experience was mind-blowing. The band, suggested to Mason by Harris, play songs from Pink Floyd’s early, Syd Barrett-led incarnation, most of which rarely or never appeared in Floyd or Gilmour’s setlists when those two entities were still touring.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

For that matter, Floyd’s original bassist Roger Waters doesn’t play much of the early stuff either. Accompanied by a suitably eyeball-searing lightshow, the band - fronted by Pratt and Kemp, who trade vocals - power through the challenging material with casual expertise, loading their sounds with a ton of effects and leaving the audience gobsmacked.

Pratt in particular has a lot of work to do in this band, playing bass parts of serious complexity against shifting time signatures and singing at the same time, while the songs move through their unorthodox arrangements.

He nails it all with total confidence, of course, joking with the audience and his band-members - and obviously having a whale of a time. As we tuck into our starter, we know this is going to be a conversation to remember.

Building blocks

This is a hell of a band, Guy. How did it start?

“Lee Harris, who used to play for the Blockheads, had the idea. He pointed out that no-one plays the really early Pink Floyd material, and also that no-one ever asks Nick Mason to do anything. David Gilmour doesn’t ask him to play and Roger Waters doesn’t ask him to play, but this is the one thing that Nick completely owns and that no-one else can really do.”

Did it come together smoothly?

“It came together incredibly easily. We did a single rehearsal in this little room, which was hilarious because I’ve only ever been in an aircraft hangar with Nick. We rehearsed for a week and then did those four shows to warm up for this tour. I don’t think any of us were ready for the reaction, although we knew we had a good band. There were five-star reviews everywhere.”

How did it feel the first time the new band played together?

Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun is the greatest song that Joy Division never wrote

“It felt totally punk and totally fresh. Interstellar Overdrive has one of the greatest punk riffs ever written. Bike is fucking bonkers. Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun is the greatest song that Joy Division never wrote.”

Have you played these songs before?

“I did One Of These Days when I played with Floyd, and in fact I didn’t really want to do it again, but it’s a signature bass piece, and also Astronomy Domine. I played Arnold Layne with David, but we only learned it for a gig at the Royal Albert Hall in 2007, when David Bowie got up and sang it.”

There are some fiendish bass parts in there.

“Yes, although obviously my years with Floyd have taught me how to handle these things. The time is totally fluid; we go between four and three all the time. On Bike, I’ve actually invented a time signature called ‘Syd/4’. You couldn’t count it if you tried, because it has so many different time signatures within it. Nick sails through it, though. He gets it in a way that no other drummer could, because no other drummer played with Syd Barrett.”

Do you emulate Roger Waters’ bass parts, or do you play the songs your way?

“I’ve never tried to replicate them. David played bass on most of the records anyway. When we did The Division Bell in 1994 he said ‘I’ll do the bass’ and I said ‘David, if I don’t play bass anywhere on this record, I’ll look like a real twat.’ So he said yes - grudgingly!”

Is David a decent bass player?

“He’s an absolutely brilliant bass player, especially fretless. All that beautiful fretless stuff on The Wall is him.”

How does Roger’s bass playing strike you?

“I’m really impressed with Roger’s playing on a lot of the early stuff. He basically invented the octave in bass as a thing. You can’t really hear his parts on the early records unless you listen really carefully, because some of it is pure Peter Hook, played up high.”

Burgundy Betsy

What gear are you using in this band?

“I’ve got a Ricky and a Precision, and Ashdown have built me a copy of an old WEM PA. I used a Zoom delay in the warmup gigs, which is the one I used on tour with David, but I’ll be using an Gurus Echosex in September, plus two compressors - one which I’m designing with Ashdown, and an octaver-compressor.

“For strings, I play Elites roundwounds and have done for decades. They’re utterly reliable. I like to change them a lot. On the Division Bell tour I had four basses, and I asked for new strings for soundcheck and then new ones for the show as well. I can’t believe I was that much of a diva.”

Will Betsy, your famous 1964 Jazz, make an appearance?

Betsy is the best bass guitar in the world. I’ll fight anyone who says otherwise

“There’s no room for a Jazz Bass in this gig, unfortunately, but Betsy is the best bass guitar in the world. I’ll fight anyone who says otherwise. It has a little date carved inside it - June 7, 1964 - which I love because it’s my dad’s birthday, and it was him who gave me my first bass. [Pratt’s father was the actor Mike Pratt, who died in 1976].”

Has Betsy been modified over the years?

“It has EMGs in it, because in Pink Floyd world, anything you say happens. I said to my tech one day, ‘These pickups are a bit quiet, maybe we should think about getting some new ones?’ - and the next morning, it had EMGs in it. I shouted ‘What the fuck have you done? You can’t put EMGs in a ’64 Jazz!’ but when I plugged it in, it sounded amazing. The tone knob stuck out a bit more than usual, but it was about five years before I realised that this is because the pickups are active and there’s a battery in there.”

You also have a vintage Fender Precision.

“That’s Eliza, also made in 1964; she’s Betsy’s sister, because they only made three in Burgundy Mist that year. She’s the loudest Precision I’ve ever heard. No mods, just straight out of the box. Mark Gooday of Ashdown found her for me and I’m eternally grateful.

“I’ve never been much of a Precision man, but all the classic Pink Floyd material was played on one, and they’re what David likes, so I need to have a nice Precision when I’m working with him. Fender gave me the one I’m playing with Nick. Their new American Professional basses are amazing.”

Do you prefer four- or five-string basses?

F*** five-strings. They were a '90s anomaly, although I do love a low D

“Fuck five-strings. They were a '90s anomaly, although I do love a low D. Status five-strings were the only ones that worked, because they had graphite necks.”

You’re a long-time Ashdown user.

“I’ve worked with the Gooday family pretty much for my entire working life. Half the time I just plug my Ashdown in and I don’t even look at the EQ, because it’s so transparent and powerful. They always work out of the box and they just do the job.

“The only time it went down was at a Gilmour show in South America, at a football stadium in Sao Paulo in front of 60,000 fans! What’s more, the stage crew had unplugged my spare amp because they decided that it got in the way of the lasers…”

Presumably you go direct as well?

“Of course, but I hate it, because sound engineers will always use a DI if you give them the option. I did Glastonbury with Bryan Ferry in 2014 and the sound engineer took a DI that totally bypassed all my effects. I had to play an intro that completely relied on delay, so people watching TV who heard the staccato notes must have wondered what the hell I was doing.”

Comedy and commerce

Your comedy show continues to be popular.

“It does, and it’s funny inhabiting two different worlds. When I play bass in my day job, I’m accustomed to staying at the Four Seasons and having someone hand me an ashtray before my ash hits the ground. With comedy, I have to schlep my gear up the steps of the Travelodge. It is amazing how your attitude to hotels changes when you’re paying for them!”

What else do you do?

“I’ve written two musicals - I’m actually just a West End Wendy underneath. I’m always amazed and humbled by how people in the theatre keep doing it because they love it, even though it’s a very different industry nowadays. The same thing has happened to the music business.

Madonna’s Like A Prayer in ’89, and having my part be such a ridiculously big part of it, is probably the biggest thing I’ve done. That and Michael Jackson’s Earth Song

“I have to apologise to any young musicians reading this, because in my salad days in the '80s, the music business was this ludicrous theme park awash with money. All you had to do was get over the fence, and once you were inside, you were off. We’d spend months going round Europe just doing TV shows, standing there like a catalogue model, and of course that world doesn’t exist any more because all the TV shows are gone.”

What’s the most commercially successful thing you’ve done?

“In this country, probably Jimmy Nail’s Ain’t No Doubt [a 1992 UK No. 1 hit] which I co-wrote and produced. I’d watched the movie Full Metal Jacket the night before and the melody from ‘I don’t know but I’ve been told…’ came into my mind. I played it on the bass, and suddenly Jimmy sang ‘Ain’t no doubt it’s plain to see…’ and that was the melody we used in the song. But worldwide, being on Madonna’s Like A Prayer in ’89, and having my part be such a ridiculously big part of it, is probably the biggest thing. That and Michael Jackson’s Earth Song.”

Musically, how astute is Madonna?

“When we did the song Oh Father, she was standing in the control room and the band was in the studio. Everyone had charts except me. I can’t read music, so I just had the chords. She just said ‘Duck eggs!’ to me, which means whole notes. She didn’t really tell the musicians what to do, just what not to do.

“Then she hit record and the whole band, and her vocal, went down. The tape ran once more for the orchestra, and then Chester Kamen came in and did guitar overdubs, and that was it. It was amazing.”

Do those sessions still come along?

“No, that sort of high-budget session doesn’t exist any more. Think about the money that it cost back then to fly me out to California in business class, put me up in a rented apartment, get me a hire car and pay me $100 a day per diems, as well as paying me $1,000 per day to do the job. All that would now add up to the cost of an entire new Madonna album.”

When were you busiest?

“As a bass player, in the mid-'80s. It was an anomaly - a time in which musicians were hip, because before and after that, musicians weren’t hip. Nowadays, music is just another wing of showbiz. There’s no difference now between being in a successful soap opera and being in a successful band. I didn’t care, though - back then all my money went on clothes and restaurants anyway. But I was really busy in the mid-'90s doing TV music, which I loved. I won awards for it.”

You wrote in your autobiography that it all dried up around 2003.

“That’s right. I had my studio at the Townhouse and I was doing songwriting, but that never really worked because all the pop writers who write for Westlife, or whoever, really love it and take it seriously, which I didn’t. I’ve got quite a good knack for writing the songs, but there’s a certain amount of belief that you need. As a result, when I hit my 40s I wanted to do something other than just playing music, so I did the comedy.”

Untapped

You’re known for playing a lot of busy, complex lines.

“Maybe, but I’m not a super-technical player by any means.”

Sure you are. Have you ever played any false harmonics?

“No, although I’ve done sliding harmonics.”

Double thumbing while slapping?

“No.”

Sweep picking?

“No.”

Tapping?

“Yes, I’ve done some tapping. In the '80s, I briefly thought about getting a Chapman Stick.”

Well, that makes you a shredder.

I’d been under the assumption that as a professional musician I’d been asked to join a gang - and that as long as I showed up, everything would be fine!

“Piss off! No, it doesn’t. The funny thing is that I remember getting good at bass, but I can’t remember actually learning how to play it. I had this idea in my head that if I learned other people’s basslines that I would just sound like them, so I just did my own thing. I remember when someone asked me if I could slap, and I said, ‘You mean this?’ and did it, assuming that they were talking about something else more difficult. I didn’t study. It was completely intuitive!”

The afternoon winds on. It’s one of those proper, old-school lunches that no doubt Pratt was accustomed to in the fast-receding heyday of the music industry, and as the wine flows, he regales us with stories of co-writing Vindaloo, the classic footie song; how Johnny Marr introduced him to Paul McCartney; how punk influenced him (“Simonon looked like a rock star. Burnel was brilliant. And I was a big fan of Foxton”), his late chum Robert Palmer (“He just got everything, and he didn’t give a fuck what was fashionable or not”) and the amusing vagaries of this strange industry (“I’m the only person who’s been in The Smiths and played on a Whitesnake album!”).

Cocktail in hand, Pratt sums up his philosophy by recalling: “A few years ago I had a ‘Eureka!’ moment where I realised that I’d been a professional musician for my whole life. Now, on paper that means that I was hired to do a job to the best of my ability and to follow all the protocols. Strangely, I’d been under the assumption that I’d been asked to join a gang - and that as long as I showed up at some point, everything would be fine!”

We chug back our drinks, shake hands and stumble off in different directions. Folks, you really don’t get bassists like this any more. Make sure you go and see Pratt in the Saucerful Of Secrets - your horizons will expand permanently.