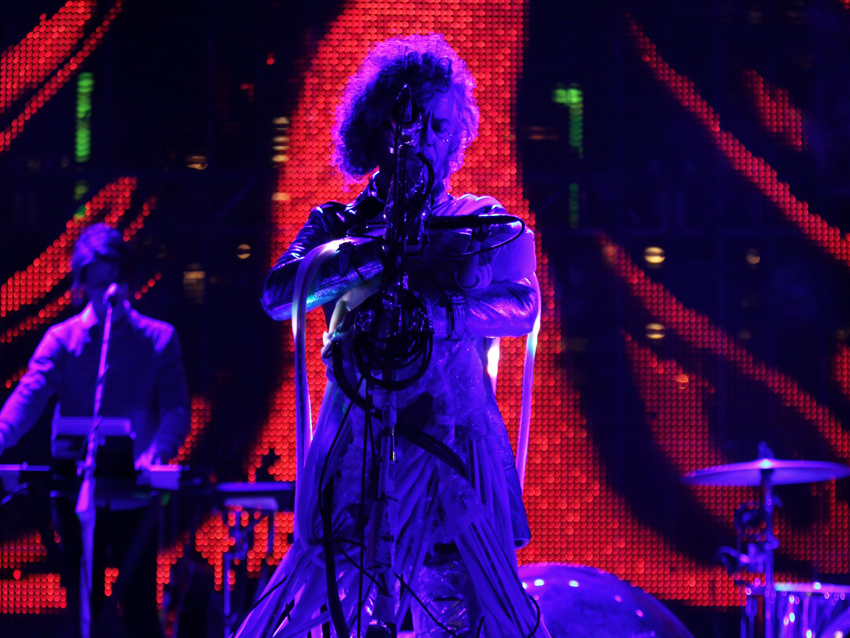

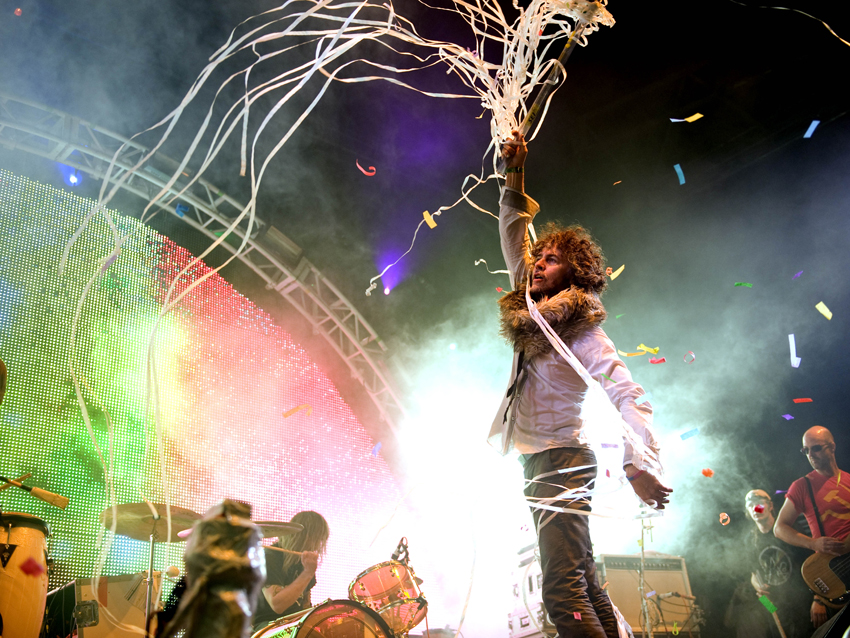

Wayne Coyne discusses The Flaming Lips' The Terror track-by-track

“Whenever we go into making a record, we do believe that we’re making 'something,'" says Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne. "There are ideas there, but at the same time, it’s also true that the best art is accidental – a happy by-product of something you weren’t intending to do."

Grand concepts and lucky moments collide beautifully on The Terror, the newest sonic trip to come from rock's reigning kings of experimental mood music. Coyne admits that the band wasn't really planning on recording an entire album, saying that the group "simply made music that appealed to us on a primitive level. We’re always recording anyway. It’s like what I tell all artists: ‘Be working hard, but be ready for the surprises.’"

Co-produced by the band (which also includes Steven Drozd, guitars, keyboards and vocals; Michael Ivins, bass, keyboards; Kliph Scurlock, drums; and Derek Brown, guitars, keyboards and percussion) Scott Booker and longtime collaborator Dave Fridmann, The Terror took shape mainly on computers and keyboards, with most of the recording taking place at Fridmann's Tarbox Road Studios in Cassadaga, New York.

Although there is an element of the full band on the album's expansive nine tracks, the project was mainly the work of Coyne and multi-instrumentalist Drozd. "Probably 80 percent of what we’ve done since Zaireeka [1997] have been just Steven and I putting things together," says Coyne. "The group is always involved in everything we’re doing, but the tracks don’t have drummers and bass players and things like that."

Between the band's Pro Tools setup, Fridmann's studio and the extensive collection of hard-to-find gear and unique synthesizers Coyne and Drozd utilize, Coyne says, "We're able to let our minds wander and create. There isn’t anything we dream up that we can’t do.”

The Flaming Lips' The Terror will be released in the UK on 1 April in the US on 16 April. The album can be ordered at this link. On the following pages, Coyne walks us through the the record's nine cuts.

Look... The Sun Is Rising

“When we made it, the thrust of the song had that real ‘this-is-the-beginning-of-something’ feeling, like at the start of Star Wars: ‘Here comes the story!’

“Lyrically, I think I’m when I’m singing, ‘Look, the sun is rising,’ it’s about how we can dread it. We want to be lost in that netherworld, like when you’re on drugs or something. It’s four in the morning, but you want to keep those moments – when they’re really good, of course – when you've escaped your own identity or your own mind. You want that to last forever.

“There have been a couple of times over the last few years when we’ve said that out loud: We think it’s four in the morning, but it’s really six-thirty, and we know what that means: ‘Fuck, the sun is coming up. We have to go back to being ourselves again. We have to be normal. Back to routines, back to life.’ So it’s just another way of looking at the sunrise.

“The sunrise is our symbol. It tries every day. It gets up every day and says, ‘Maybe today will be glorious.’”

Be Free, A Way

“Part of our agenda was that we purposely couldn’t use anything that was making rhythms. We don’t really set limits for ourselves, but sometimes when we would do a song, we would have to find something that reminded us of a broken refrigerator whirring in the background.

“So we thought, ‘We’ll start with these clumsy little machines, these robots being the rhythm section, and that’ll maintain the humanness.’ I don’t know if this is one of the million little synth patterns we got off of this synthesizer from Sean Lennon. It’s this Wasp Synthesizer – it’s not a toy, but it’s a little plastic thing.

“The beauty of it is, you can get a sound on it, but it’ll disappear on you as you’re making it. It’ll shift around and do stuff, and you don’t even know if you can get it again. It was like, ‘Well, that’s the rhythm. Hope you like it, ‘cause we’re working on something that we can’t redo.’ And that’s cool. We like working with things that are destroying themselves as they go.”

Try To Explain

“Steven had this sort of haunting melody that came to a crescendo. We didn’t have lyrics for it, but we knew it that was a big moment when it breaks into [sings] ‘Tryyyyyy to explaaaaain!’ When I heard it, I really tried to sing what I thought the music was saying. The nature of the song is shattered by this emotion.

“I didn’t dwell on it that much, but I think that people read into it as my life is like that. Elements are like that, but I think that’s the same for everybody, where your mind is left tortured by something that’s unanswerable. ‘Try to explain, I don’t think I understand’ – and you never get an explanation. To me, that sounds like the way people think.

“Everybody I’ve talked to will go to this song and say, ‘It haunts me. I’ve played it 100 times, and I know what you mean, but it still haunts me.’ I think that’s just sheer luck from doing so much music; that is, you can be vulnerable, you can be honest, you can be stream-of-consciousness, and you can be saying nothing and saying everything at the same time.”

You Lust

“It’s got a cool riff that started from a jam session, some of which was just a calamity. That riff only happened for a moment, but I recorded it on my phone as a video. I liked it, and I thought, ‘Let’s revisit that when this jam is over. We’ll look at the video and wonder what we were playing.’

“But we could never really redo it, and we wound up using my phone. That’s why that track sounds so strange. There’s elements that have sort of a Doppler effect, because I’m moving the phone. We really liked the phase-shifting elements that happened with me walking around the room.

“There’s a lot of great, fucked-up accidents like that. I think a group that hasn’t made as many records as us probably would have rejected that. But working so much in the studio, and working with master musicians like Steven, you welcome any little nuance. This song is unique."

The Terror

“The main sound that begins The Terror, and it’s on all the tracks, I think, is this iPad app that Steven put his voice into and turned into an electric choir. It’s extremely haunting, and we found we kept coming back to it. So now the song even begins with Steven’s voice that was made into his own synthesizer.

“That really is the secret as to why this is such a long piece. You’re not really hearing instruments so much; you’re hearing a lot of the human voice, even though it’s been put through synthesizers and shit. It becomes emotionally evocative.

“Steven started doing this thing, and I knew immediately that I could sing something to it. We were playing along, not really knowing what we were doing, and some of the sounds that we used were really fucked-up, distorted, heavy, tri-tone things – some of them electric guitars, some of them keyboards put through different reverbs and effects.

“A lot of this record is very gentle, but some of it is very stabbing. I think this song is probably the peak of the aggression. What’s interesting is that the intensity doesn’t destroy the gentleness. We don’t show restraint, but sometimes restraint happens. That’s why we love this song. Truthfully, it’s still mysterious what’s happening here.”

You Are Alone

“We think of this song as if you’re in church, and you’re just peering up. Not that any of us goes to church, but we understand the concept of screaming up to the universe and going, ‘Am I alone?! What’s going on here?’ And the universe talks back and says, ‘You are alone.’ [Laughs]

“We know that there’s an element in our music of being trapped in the isolation your own mind. But what do we do about that? Once you acknowledge to yourself that you are trapped inside your own mind, you either find a way to deal with that, or you go insane, or you take drugs or whatever. But there’s something about acknowledging it, which is what we do in this song.

“’Am I alone?’ It’s like, everybody’s alone in the same way that you’re alone.”

Butterfly, How Long It Takes To Die

“This is a song that we did in an earlier session. We heard it and thought that maybe we could change it and make it seem like it was part of The Terror. It's interesting that it has more rhythm and bass than any track on the record.

“I think we really made the song fit the lyrics. There’s light at the end, and you can see the universe making a new sun and a new sky. You can see the universe is ending, making a new dark and a new night. Part of that is the acceptance of the brutal truths that The Terror is: if you know ‘this,’ then you must know ‘this.’

“The analogy that we sometimes use is that you’re seeing your mother or your brother dead on the table, and somebody has to pull down the sheet. Their faces might be completely mangled from some horrible car accident, but you have to remember what they looked like in your mind. You have to remember the beauty, even when you’re confronted by something terrible.”

Turning Violent

“The explosion at the end – people might hear that and go, ‘What is that?’ And they should, because it’s this very old synthesizer that Steven bought from some guy. It weighs about 600 pounds. It’s got this trigger release that works in the opposite way. You hit it and it goes ‘Brrr-rrrr-rrrrggghh!’ You let it go and it does this long trigger – “Pssssoooohhhh!’

“He kept hitting it, and I said, ‘We should just use that as a rhythm track.’ He said, ‘No, because the minute I pull it up, it does this other thing,’ and I was like, ‘I know. That’s what makes it great.’ So that’s what you hear. It warbles along in a very menacing way, and then ‘Bam!’ – it explodes.”

Always There, In Our Hearts

“We knew we were going to do it as the last song on the record. I think we looked at it like the song that ends Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon. It’s this summary: If we believe ‘this,’ then we must believe ‘this.’ If we think ‘this’ is true, then we must accept ‘this’ as true.

“It sort of repeats, like a mantra. It’s like you’re getting ready to jump off a bridge, and you’re telling yourself, ‘This is what I want. I’m scared, but I want this. I have to do it.’

“And then it breaks to the end, when it says, ‘The joy of life can overwhelm.' That's The Terror. We’re deciding we’re going to live our lives up on this higher level where we get more sunshine. It’s almost as if the more joy we seek, the more pain we’ll feel, too. But we can’t live any other way, and we’re accepting that. We’ll have joy, but we’ll also have pain.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.