Martin Taylor discusses his glittering guitar career

The jazz great on his influences, inspiration and insight

Introduction

Essex jazz-fingerstyle maestro Martin Taylor is one of the world’s foremost guitarists, renowned for exceptional solo chord-melody composition (and improvisation) skills that have earned him countless awards and garnered him an MBE into the bargain.

Here, he looks back over an amazing career and kindly shares some of the insights he's gained along the way…

Musical youth

“I was three years old in about 1958, and my mum was giving me a bath in the kitchen sink; it was raining outside and I saw my dad coming up the garden path with a parcel under his arm. He came in, opened the box and inside was a red ukulele with a picture of a palm tree on it. I started playing on it straight away so, as a result of that, I don’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t playing.

“My dad was a musician, though he didn’t really start playing until he was about 30. I remember him listening to a lot of Django Reinhardt and Eddie Lang records in the front room with his friends and he starting playing from then. I became fascinated with the music and literally grew up with it. So it’s not like I discovered it one day; it was always there.

“Probably my second memory is of a guitar and amp arriving at the house. My dad had ordered it from Bell’s catalogue to learn on. It was a Hofner President with a little Watkins amp. I can remember the excitement of the case opening and seeing this brand-new guitar inside.

“I remember the smell of the wood, it was magical. As soon as I could, I wanted to start playing; I was already more interested in playing music than listening to it. I just wanted to be a part of it.”

Getting serious

“My dad showed me a few chords, which got me started, but then he decided he wanted to play double bass, so he bought a bass. I didn’t inherit the Hofner though, it was too big for me at the time; I was still only four! My dad had sold it by the time I was big enough to have been able to play it.

“I suppose I really got serious about the guitar when I was eight. A music store opened in town and I used to go there with my next-door neighbour, Gypie Mayo (later of Dr Feelgood and The Yardbirds). We started playing around the same time.

“A friend of my dad’s was Dick Bishop, who played guitar with Lonnie Donegan. He used to tour Europe with Big Bill Broonzy and would bring records back. Gypie and I spent all our time listening to either Django Reinhardt or Big Bill Broonzy. Ultimately, I went in the jazz direction and Gypie went in the blues direction.”

Chained to Django

“My dad had lots of Count Basie and Duke Ellington records, so I listened to a lot of big bands along with sax soloists such as Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster, but there was something about Django that appealed to me although I didn’t understand why.

“Listening to Django, I used to think he was talking to me with his guitar, so I felt a real, direct connection with him. Of course, now I realise that what I was listening to was a great melodic and lyrical improviser; he was a musical storyteller.

“My dad gave me the best lesson of all when he pointed out to me that Django was improvising. I asked him what that meant, and he said, ‘Well, the band are still playing the chords but Django is making up a new melody on the spot.’ This is how I teach my students today. I encourage them to think melodically rather than base solos on chords and scales.”

Melody maker

“I don’t like it when guitar players ask what scale they can use on this or that chord. When you think back to the great early improvisers like Louis Armstrong, they started with the melody and expanded from there. They weren’t thinking so much about chord/ scale relationships.

“With my students, I always start them with the melody. Of course, they have to know the chords to the tune, but I show them how to use the melody as a springboard for their improvising. In fact, I don’t even call it improvisation; I call it ‘variations’.

“Improvising needn’t be as complicated as some players make it out to be. I tell my students to start with the melody, then embellish the melody either by adding a few notes or taking some away. Then start to explore chromatics in and around the melody. From there, they can take it as ‘outside’ as they like but as long as the basis is in the tune, it’ll sound good.”

University of life

“You have to remember that I learned by playing gigs. Sometimes those gigs would require me not to play any jazz and stick to the tune religiously. A lot of people learn nowadays with YouTube in their bedrooms, where you can do what you want.

“In my day, if you wanted to play, you had to join a band and go out and do gigs, so we learned ‘on the job’. We’d play these quiet gigs like a restaurant and we’d see how much we could embellish a melody without getting arrested! So it wasn’t conscious, it’s just that I’m from the era where the gig was your music school.”

Road worn

“I’ve been on the road for 40-odd years but for the past 15 years, my son has been managing me. We look at the year and decide what we want to do. I always spend a few months in the US but also go regularly to the Far East, Europe and Australia.

“I have to spend a lot of time touring as I live in Scotland, a small country. Think of how many of those people would actually be into jazz anyway! It would be impossible for me to make a living there, so that’s why I go around the world where over the last 40 years, I’ve slowly built up pockets of people that like what I do. It’s not like I’ve got the wanderlust. I have to go to them, they can’t come to me.

“Most of my tours are solo but I also record and tour with Tommy Emmanuel and Martin Simpson. I love collaborating with other guitar players. I spent January, February and April this year in the US with a show called The Great Guitars with Frank Vignola, Vinny Raniolo, Peppino D’Agostino and myself.

“I’ve been touring the States for 35 years and before I left, I told my wife I thought this would be my last tour of the US. The first show was at Yoshi’s, a jazz club in San Francisco. We had a fantastic audience and the four of us sounded so good together. On stage, I thought to myself, ‘This is magical’. So, already, that plan I had to wind things down a bit went out the window, as all the dressing-room talk later on was about how great it was and how we should fix more tours.

“I also teach, record, compose music and design guitars so I have other income strands, but it’s the live playing when you think, ‘this is what it’s all about’. It’s hard living on the road, but I like what bassist Danny Thompson said: ‘I play for free, but I charge for all the other stuff ’.”

Finger buffet

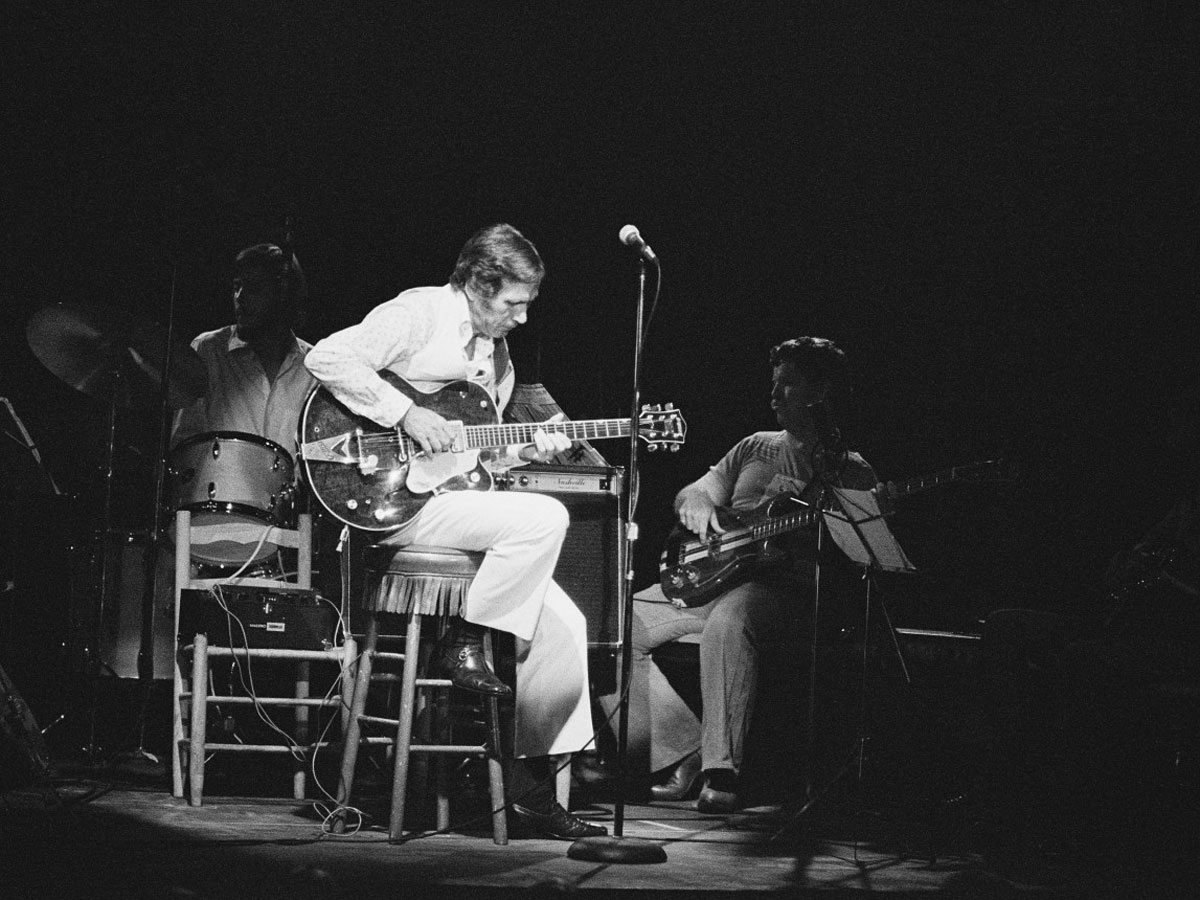

“I played purely with a pick for the first 15 years. Around 1977, I became interested in playing solo, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. I worked a lot with piano players then, and was always jealous of their freedom to play simultaneous chords and melody.

“I’d heard fingerstyle players like Chet Atkins and heard classical time to do it!’ I didn’t know how I would keep up with it all while on the road so much, and I hadn’t done much teaching anyway. I had done what they call mentoring sessions for established players, so, if anything, I was a guitar psychiatrist, not a teacher!

“After talking to David, he convinced me I’d be right for it, so the first thing I had to do was analyse my playing as I’d never had lessons and didn’t know how or what to teach.

“I set up a studio at home and got a camera for travelling with so I could respond to my students’ progress from anywhere in the world. They send me film of themselves playing through a lesson and I comment and advise them with a filmed response of my own.

I now have a whole guitar curriculum on the Martin Taylor website, which students can work through in their own time. The video responses go on the site, too, for other players to see, which students find very helpful. So it becomes interactive.

“There’s a thing called ‘Coffee Break’, where I’ll film myself talking about a particular issue students may be having; and another called ‘Guitar Conversations’, where I get together with well-known players and talk guitars, technique and all sorts of stuff.

“I’ve recently started doing guitar ‘retreats’ - like a guitar holiday. They’re becoming very successful. Over the years, I’ve developed a method for teaching and I’ve come to really enjoy it as my confidence as a teacher has grown.”

Reading the lines

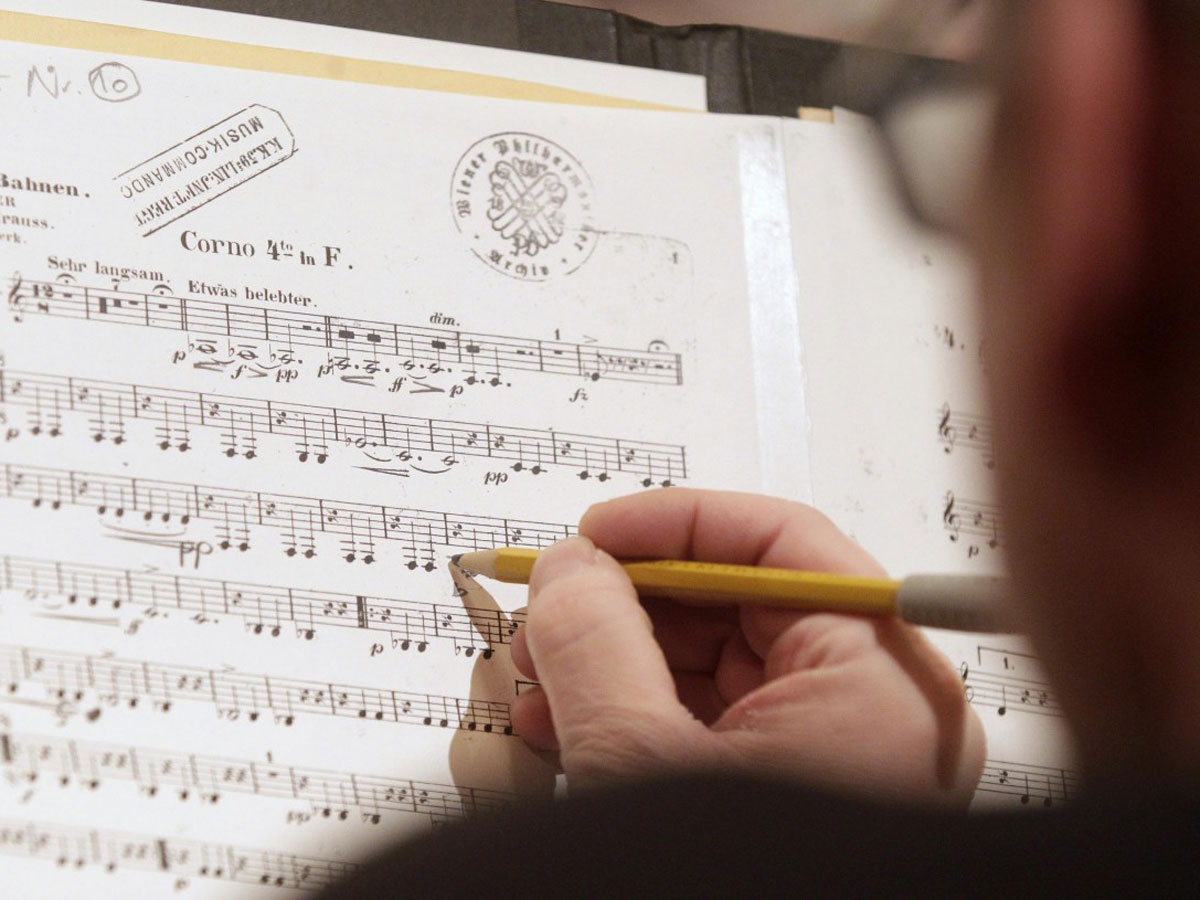

“I think it’s a really good thing for guitarists to learn to read music. It’s the best way for musicians to communicate with each other. Before the Great Guitars tour, we would send each other charts for tunes we wanted to play, so by the time we got there, we could play them.

‘When I say read music, I don’t necessarily mean sight-reading - that’s a different skill altogether - but the ability to read some music can open up a whole new world. I’m not keen on tab as it’s only relevant to guitar; you can’t communicate your ideas with other instrumentalists, so it’s limiting.

“I do use tab along with music notation with my academy, but I try to wean my students away from it. For me, it turns guitar into a mechanical exercise, so I encourage people to learn musical notation.

"It’s much easier to transfer what you learn on one piece over to the next with notation, as you learn more about the relationship between chords and intervals, music’s building blocks. Tab just tells you where to put your fingers.”

Carry on plucking

“What keeps me going is I still enjoy the guitar and feel totally connected to it when I’m playing. Having said that, if I’m off the road, I don’t play at all.

“I’ve never been an obsessive practiser and can go long periods without playing. I’m not like Tommy Emmanuel, who’ll get his guitar out at the airport and start playing! I do my practice in my head. As for where I see myself in 10 years... probably in a nursing home!”