Joe Bonamassa on the surprising tones behind Blues Of Desperation and being "the most overrated guitar player in the world"

"I sold all my Dumbles"

Introduction

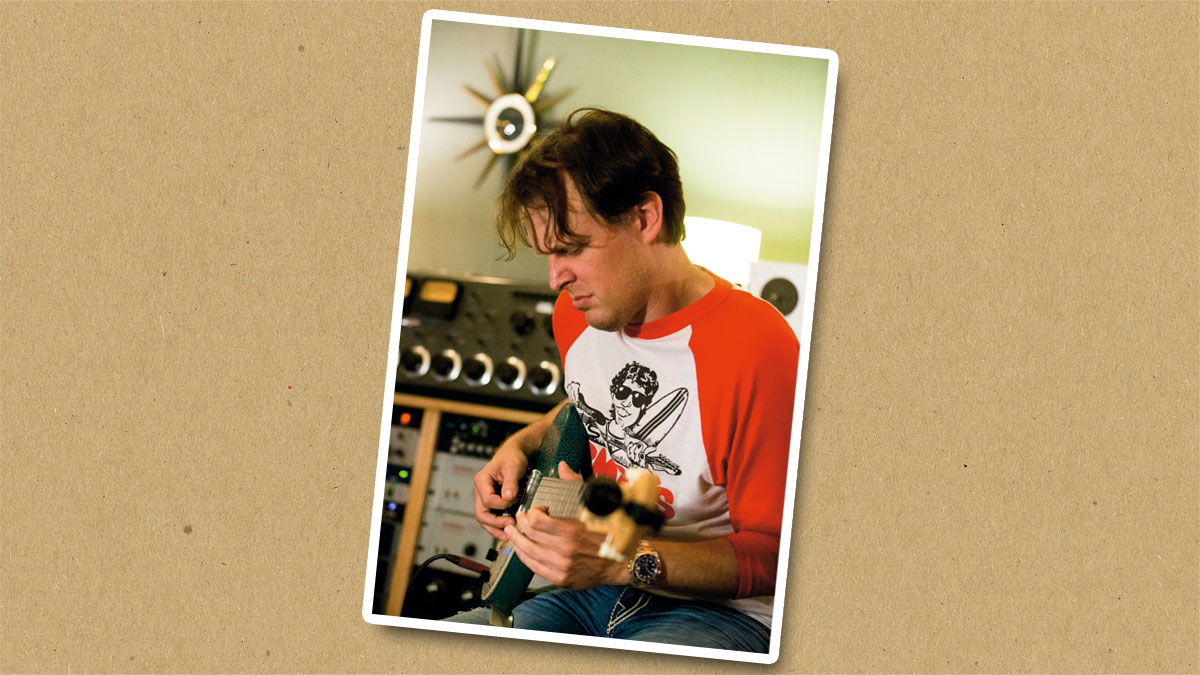

Joe Bonamassa’s new album, Blues Of Desperation, is arguably the biggest-sounding, tonally-rich set of tracks the blues-rock virtuoso has released to date.

In just five jam-packed days, Joe, his drummers, and the rest of the band thrashed out the album’s 11 original tunes

Hooking up with producing consigliere Kevin Shirley for the eighth time in the studio, Joe shook things up by bringing in not just one, but two drummers into the hallowed surroundings of Nashville’s Grand Victor Studios - formerly Chet Atkins’s famous RCA Victor facility.

In just five jam-packed days, Joe, his drummers, and the rest of the band thrashed out the album’s 11 original tunes. And, as can only be expected from a renowned gear collector like Bonamassa, Grand Victor was suitably overflowing with a veritable bevy of beautiful guitars and amps during the sessions.

We chat with the man himself to find out exactly how he nailed Blues Of Desperation’s spectacular tones. Over to you, Joe…

Don't Miss

Joe Bonamassa showcases the best of his breathtaking guitar and amp collection

Joe Bonamassa: 10 guitarists that blew my mind

A power quartet

Did you have an over-arching musical vision when writing Blues Of Desperation?

“Well, I knew who was showing up for the sessions. It’s been a while since I got back to just straight-ahead blues-rock, which quite frankly is probably what I’m best at.

With two drummers, it becomes like a power quartet so that was an interesting combination of things

“I wanted to make a heavier record but I also wanted to make another all-original record. And, once I got my head around it, it was a really fun experience to write for this group because you could do anything with this band. We jammed a lot of the tracks. A lot of them hadn’t heard [the songs] and it would just take them usually second or third take.”

There are two drummers, Anton Fig and Greg Morrow, across the tracks. How was it playing with two drummers in the studio and what impact would you say it had on how the finished songs ended up?

“With two drummers, it becomes like a power quartet so that was an interesting combination of things. I think Kevin [Shirley, producer] kind of put the two drummers off their game a little bit at the beginning.

“Usually when you have two drummers, somebody is doing the meat and potatoes and then the other drummer is doing stuff on top. And Kevin flipped things around. Anton is used to doing the meat and potatoes but Anton became the guy on top and Greg was the one doing the meat and potatoes.

“Once it settled, it was awesome. Having the two drums was just such an anchor to solo over. It’s like the time’s not moving and it’s just a big train and it just makes the notes sound bigger. That was really inspiring.”

Don't call me Shirley

You’ve been working with Kevin Shirley since 2006’s You & Me. Could you sum up how your relationship works in practise?

“We’ve been working together for 11 years and, you know, the same deal that we cut in 2005 is the same as it is today. When we first started, Kevin was like, ‘You have to trust me that I have your best interests in mind.

A great producer really challenges the artist to get the best out of them

“I may lead you into things that you wouldn’t instinctively do but trust me that it’s going to work out!’ I said, ‘Okay, great!’ and, 11 years later, we still have that exact same deal.

“We just did the acoustic tour and we cut a DVD at Carnegie Hall a couple of weeks ago… and [Kevin] was like, ‘I’ve got a cover song for you to do’. I was like, ‘Sure, I’ve got one, too… How Can A Poor Man Stand Such Times And Live?’ - which is an old folk song and Ry Cooder did a great version of it.

“He said, ‘Oh cool, I like that… here’s mine, Bette Midler’s The Rose!’. I’m like ‘What the fuck are you saying? Bette Midler?’ He goes, ‘I had our friend Doug Henthorn demo it for you, so listen to his version… don’t listen to Bette’s version!’ So Doug demoed it in a key that he thought was right for me and I’m like, ‘I can do this!’ And it turned out to be the star - it was the encore song at the Carnegie Hall DVD and people loved it!

“That sums up my relationship with Kevin Shirley right there. It’s his ability to find stuff or put me in situations that initially make me either want to run away or feel very uncomfortable, but once I get my head around them, they turn out to be great. That sums up what a great producer really is, challenging the artist to get the best out of them.”

Bye bye Dumbles

How did you decide what gear to use?

“Because of the way it worked out last year, we were in the middle of a touring cycle and I had stuff kind of spread out so I ended up using my main live setup, which is the two hi-powered tweed 1959 [Fender] Twins and two [Fender] Bassmans [1957 and 1958]. Most of the record is that rig.

The high-powered Tweed Twin is just a jewel of an amp. You can play heavy metal through these things and they sound massive

“I also had a tweed [Fender] Champ, which is the fuzzy part on the song, Mountain Climbing. That’s the tweed Champ and not a fuzzbox. I had a Marshall Bluesbreaker combo which I used on one song only. I had a brown [Fender] Deluxe, from 1962, which is my favourite amp. Then, I had a GA-40 Gibson Les Paul amp from 1959 and I had a reverb spring. I like to record with a reverb spring because it gives a nice sheen to the sound.

“As far as guitars, I had a ’59 Les Paul that I call ‘The Snakebite’, a ’51 Nocaster, a ’57 Blonde Stratocaster, a ’58 Gretsch Country Club and a [Gibson] Firebird III. Then I had a couple of acoustic guitars, including the Grammer Johnny Cash and this Epiphone FT-45 Cortez 1964.”

So how far had you visualised the tone for the songs on this album before you cut them in the studio?

“It’s weird, this is the first album that I’ve done that didn’t include a Marshall Silver Jubilee, any kind of Dumble-style amp or a Dumble itself. I sold all my Dumbles. I had three at one point and I sold them all.

“One I traded for a ’59 Les Paul, which I get way more joy from. Two years ago, I mothballed that whole cliché of the rig I’m most associated with - the two Marshalls and the two Van Weeldens and the Dumbles and the effects board and everything.

“The high-powered Tweed Twin is just a jewel of an amp. You can play heavy metal through these things and they sound massive. It does clean amp, it does distorted amp, it does anything you want it to do and all of your sounds are in the control of your volume on the guitar.

“Basically, whatever guitar you put through that rig, it gives you the best and optimum sound of that guitar. All of those classic tones come front and centre as soon as you plug into the tweed amps. It’s been a real life-changing event for me. The other thing about the setup of the tweed rig is all the speakers are Celestion. I can’t use the original Jensens because the Jensens will just collapse.”

Setting up

What actual amp settings did you use in the studio and how far do use the same settings live?

“All the settings are exactly the same. It’s weird. For any tweed amps that have a mid-range control, I go into the bottom bright input. The normal’s off. The sweet spot’s between nine and 10 in the gain. The treble is between eight and nine, mostly nine. The mid-range is at nine. The bass is off!

The Firebird with those mini-humbuckers. It’s brighter than a Les Paul but not as bright as a Fender

“In a bright room the bass maybe comes up to about one or less, just depending. The Twins are set identically to the Bassmans. I set the tweed Deluxe the same way, with the tone at nine and the volume between nine and 10. I use the same settings live. They’re as loud as they go. Anything above 10 and they start to collapse.

“You know that classic Neil Young tone on Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)? That’s the sound of a tweed Deluxe all the way up. They just completely collapse but, if you roll them back to about nine and a half or 10, you get this awesome creamy overdrive.”

Tonally, did you purposefully choose particular guitars for specific tracks?

“Some of them were obvious, like I use a Firebird III in Mountain Climbing and I used a Firebird III on Blues Of Desperation. Sometimes, the Les Paul - at least in the studio - can get a little dark-sounding especially with the humbucker, and sometimes a Fender gets a little too thin and too bright and it loses the meat.

“The compromise in all that is the Firebird with those mini-humbuckers. It’s brighter than a Les Paul but not as bright as a Fender and it worked perfectly for Mountain Climbing and for Blues Of Desperation. I really channeled Johnny Winter on Blues Of Desperation, because it was that front pickup and the sound was just working.”

Overrating it

Were many effects pedals utilised?

“I used two pedals in the studio and I use two pedals live. I use a Joe Bonamassa Cry Baby, which Jeorge Tripps designed for me and Dunlop makes. Also, I had been using this pedal called the Overrated Special of which there were only two in existence, but then last year we [Joe and Dunlop] decided to make a small batch of a thousand pedals for the public.

On a Google search of my name, I’m [described as] the most overrated guitar player in the world, which I’ll take all day long!

“I still use the Overrated Special. What the pedal is designed for is to augment an already driven signal. I start with the tweed amps at nine and a half so there’s some gain there. When I put the tweed rig together, I had three pedals.

“I had a Tube Screamer, I had a Klon [Centaur], and I had an Overrated Special and I said, ‘Let the best man win!’ So I got the tweed amps going and the Tube Screamer sounded a little thin, the Klon sounded - let’s just say ‘overrated’! - but the pedal that Jeorge Tripps built (but was yet to be named) sounded fantastic!

“It becomes the tweed rig plus. It didn’t disturb the harmonics and the overdrive, it didn’t disturb the bass and it certainly didn’t disturb the high end and I go, ‘That’s a winner!’ and he’s like, ‘Cool, what do you want to call it?’ I go, ‘Call it the Overrated Special!’ just as a joke.

“Two articles down on a Google search of my name, I’m [described as] the most overrated guitar player in the world, which I’ll take all day long… so it was just a little inside joke among geeks!”

Go big or go home

Do you remember how you felt when you heard the final mixes?

“I loved them. I think Kevin’s done a great job mixing. It sounds big and bombastic. When I heard Mountain Climbing for the first time with that ambience, I was like, ‘Wow, that’s big!’

Grand Victor is huge. That was Chet Atkins’s studio for orchestra dates

“I think it had something to do with the room. There were two drum kits, myself, Michael Rhodes [bassist], a collection of guitars, a bunch of amps, a bunch of road cases, guitar tech stations, a whole camera crew, nine grand pianos and there was still room to park five cars. It was literally that big.

“Grand Victor is huge. That was Chet Atkins’s studio for orchestra dates… so part of the sound on this album was a loud, loud band playing loudly in a big room. That’s old school.”

Don't Miss

Joe Bonamassa showcases the best of his breathtaking guitar and amp collection

Joe Bonamassa: 10 guitarists that blew my mind