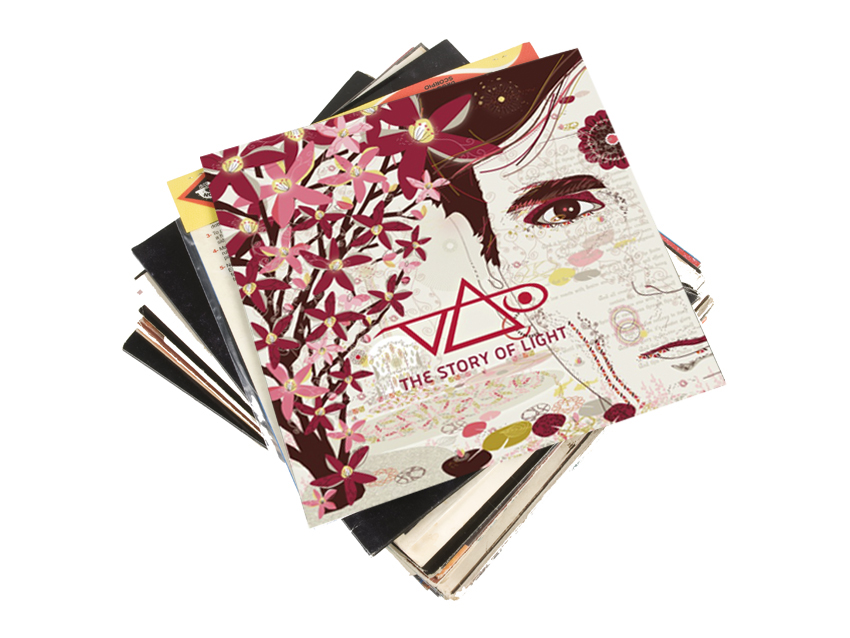

Interview: Steve Vai talks The Story Of Light track-by-track

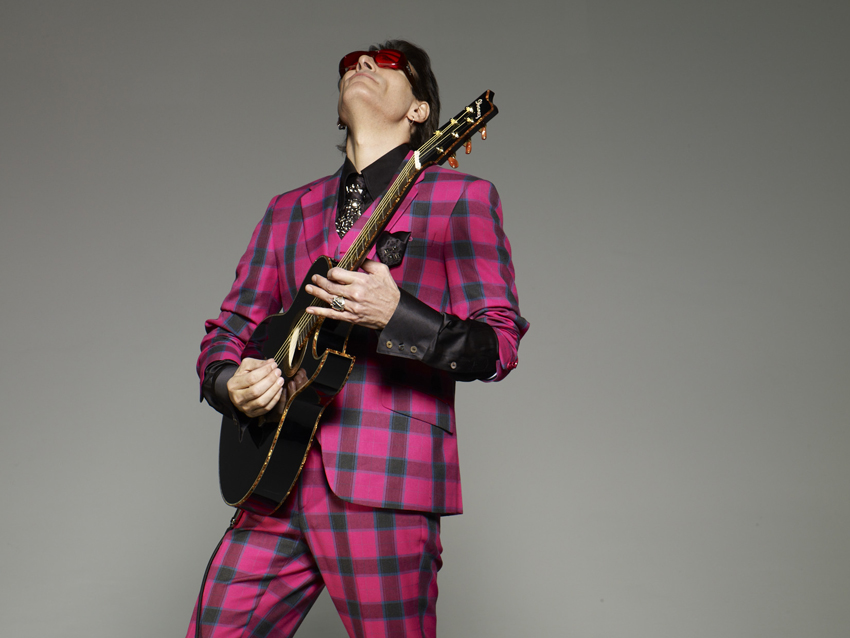

Steve Vai can be astonishingly, almost frighteningly nonrepetitive, and on his masterful new album, The Story Of Light, he travels to new places, both sonically and emotionally. “As you evolve as a player, you keep going out on a limb," Vai says. "Sometimes it pays off, and I know for me, this album has been a very rewarding experience."

Viewing The Story Of Light in context with his past work, Vai sees a common thread in that "they have my DNA all over them." Even so, the guitarist admits that "there’s a harmonic, melodic sensibility that I always kept at bay, until now.

"Perhaps I was insecure, or maybe I just had to live a little – I’m 52, so there’s a lot of experiences I have now that I didn’t then – but I was able to let go on this album and open up more. Things come into your soul and your heart, and as a musician, the key is to recognize those feelings and express them in a pure, sincere and authentic way."

Vai recorded The Story Of Light in stages, beginning around January of 2010. During this time, he surrendered to what he calls a "certain cavalier attitude" that he says is relatively new to him. "I threw caution to the wind," he says, "because really, what do I have to be cautious about? Age comes into play here. You start to think, I may not have a lot of time left here, so what do I really want to say? And what’s the worst that can happen? That I’ll fail? I don’t feel as if I have anything to lose. I don’t have to pander to radio or record companies, so I can stick to my own artistic sensibilities. If I remain true to what’s in my heart, that’s all the success I need."

The record is largely instrumental, but there are some bracing vocal moments: Vai himself sings on the heartbreakingly personal The Moon and I. Elsewhere, he's joined by guests such as Aimee Mann, who duets with him on the compelling No More Amsterdam (she also co-wrote the song), and Beverly McClellan, a season one finalist on The Voice, who tears it up with Vai on a version of Blind Willie Johnson's John The Revelator, a track so forceful that it deserves to be called controversial.

Other musicians who contribute to The Story Of Light are guitarist Dave Weiner, drummer Jeremy Colson, bassist Philip Bynoe and harpist/multi-instrumentalist Deborah Henson-Conant, all of whom will be joining Vai when he takes to the road in August.

Of the record in whole, Vai enthuses that it has "everything I like on my albums: big, intense compositional pieces; dense harmonics; really stripped-down guitar, bass and drum tracks, and the soaring seventh song ballad that just takes off into the unknown.

"So there’s a continuity of diversity, of different atmospheres, and it comes down to what I hope is a purity of vision – that’s what I shoot for, at least. What I care about is the atmosphere that I’m trying to capture. And I think I got it here."

You can pre-order The Story Of Light - and we know you'll want to - right here.

On the following pages, Steve Vai walks us through the staggering achievement that is The Story Of Light track-by-track.

The Story Of Light

“I don’t think I approach my songs differently from other artists. You get a big picture of it, and you imagine the song and hear and feel it, and that big picture is like a snapshot, and it comes to you as fast as it takes to click a camera.

“The idea was to create this giant wall of lush chords, all of these distorted guitars. I used a seven-string, which allows you to play chords you just can’t do on a six-string. So I had this wall of sound, but underneath that I wanted a rushing underbelly of what could be called polymeters.

“The construction of the rhythm was a feeling, and if you truly feel a particular way when you create something, it’s impossible for that feeling not to be represented.

“For the second part, I wanted a long melody, one that sounded endless, but I didn’t want it to sound like a solo. These things sound impossible, but they’re accessible. It’s a very carefully orchestrated part. I had to get very forensic with it. I worked on every phrase. When I broke it down, I asked myself, ‘What are you going to do here that you’ve never done before, never heard before, but it makes you feel good?’ And that’s why the phrasing is so intricate.

“It was a lot of work, but I’m very happy with how it came out.”

Velorum

“I wanted an uptempo piece, but I didn’t just want to do 4/4. It goes through lots of changes, but it’s melodic. I broke out the seven-string for this song, too.

“I think one of my favorite parts is the solo section, with those heavy rhythms played across the drum part. If you listen to that, it’s very heavily orchestrated. You need a special guy to play that stuff, because it’s not just complex in the conventional sense; every little hi-hat part, every little hit, it all has to be placed a certain way so that it complements the grand scheme of things. Jeremy Colson is so patient and so enthusiastic to be able to do it all – he’s really something else.”

John The Revelator

“This one might be a shocker. ‘What is he doing?’ [laughs] When I was growing up, I was never a big blues fan – I was more into rock and complex things. All the blues I heard sounded simple, and I really didn’t understand it. It wasn’t until I got older that I went to the roots, and that’s when I really appreciated it. Anything that has an authenticity stirs me.

“I was talking with Tom Waits, who told me about this guy Harry Smith, an eclectic archivist. He collected these amazing tracks which the Smithsonian turned into The Anthology Of American Folk Music. I never go anywhere without it. I listen to it over and over. It’s an essential collection, and I’ve researched so many artists who are on it.

“When it came to Blind Willie Johnson and John The Revelator, I was completely stunned. It’s so mysterious and heavy – and I started hearing it in my head with heavy guitars. I licensed a sample of the recording from Sony and built John The Revelator around it.

“I noticed that there have been other versions of it, one of which being from the Counterpoint Singers, this choir in the Midwest. It stunned me – so good. I tried using their recording, but it didn’t work out sonically. I loved their vocal arrangement, so I hired ten of LA’s best singers who came in and sight-sang it for me. I triple-tracked them and turned it into a huge vocal thing.

“It’s not conventional, it’s not gospel – it’s got these huge heavy metal guitars. I love it. I used an Ibanez Strat on it, and it’s plugged into a [Carvin] Legacy. The sound came from the room. It was the first thing I recorded in the Harmony Hut. I pounded the room with mics.

And then there's Beverly. I knew I wanted vocals on the song, but I just didn’t think I had the voice for it. As it happened, I was hosting this event for NARAS, and Beverly McClellan was there, too. I was totally blown away by her – the way she emotes, the power in her voice. I just said, ‘There it is. There’s my John The Revelator.’

“It’s funny. A lot of people who aren’t in my particularly genre, I guess I think they have a perception of me as this weird guitar shredder from the ‘80s. But Beverly was waiting for me in my dressing room, she had her CD, and she said that she was a big fan of mine. I was pretty surprised. I said, ‘I want you to sing this song on my album, you’d be perfect for it.’ And let me tell you, she nailed it! She’s coming out on tour with me.”

The Book Of 7 Seals

“When the choir from John The Revelator kicks in, the sort of Midwestern phrasing of theirs, I thought it was so cool, so I cut it in half and it became The Book Of 7 Seals.

“It was really nice to work with the singers and put the heavy guitar and organ on this. I didn’t want to do what I call a ‘freeze-dried’ presentation – you know, the way people take a very conventional hip-hop groove and put it to very conventional gospel singing. I put all the things together here that got me excited, and it became very compelling.

“If you have a fierce vision for something, you have to follow it. When you do that, all the criticisms that people might have – ‘You can’t do that’ or ‘Hey, you’re a guitar god, you should be doing this’ – they all go away.”

Creamsicle Sunset

“I had the riff, which was an exercise I did with chords, kind of like Chord Theory 101. It’s just an inversion of an E triad, but I never heard it as music before. It was just a way to learn an E chord. But when I did it, I thought, This is beautiful, and the whole thing came into view for me – the way I would evolve the triad, how it would resolve.

“It’s played differently every time. The guitar is such a receptive instrument: You can apply a pick to the strings and get one kind of sound; you can strum it with your thumb and get another sound; you can pluck it with your fingers and it’ll sound different – the combinations are endless.

“For people who don’t know what a Creamsicle is, it’s an orange sherbet with an ice cream center. It’s funny: You can remember exactly what it’s like to eat a Creamsicle as a kid on a hot summer day, and if you taste one as an adult, suddenly you’re right back to being a kid again.

“Now, one time I was watching a sunset in Hawaii, which is unlike any kind of sunset I’ve ever seen in any other part of the world. The sky has these orange and creamy white streaks. I thought, If I could taste that sunset, it would probably taste like a Creamsicle. And then I thought, If I could hear that sunset, what would it sound like?

“There’s a bit of a Hawaiian vibe to it, very dreamy. Approaching the guitar part, I wanted to touch the instrument in different ways. I wanted every note in every chord to have its own identity, its own zip code.

“Guitar-wise, for about 60 percent of the record, I used Evo, and on 30 percent I used Flo. Some of the background stuff is other guitars – a Les Paul here and there, various hollowbodies. For this song, I really wanted a Strat sound, so I used an Eric Johnson Strat and put it directly into an old Bandmaster head. That’s it. Everything else is fooling around with finger placements.”

Gravity Storm

“This was a riff that just came out. I recorded it on my iPhone, listened to it later and said, ‘OK, this is a keeper. I want to do something with this.’ A lot of people think I’m using a whammy bar on it, but it’s all finger bends. The guitar I used didn’t even have a whammy bar. You can’t get that sound with a whammy – the note starts someplace, goes somewhere else and then returns.

“When I heard the riff, I painted this picture of a track that had bends on all of these phrases. It was like a big-picture thing. I wanted it to sound heavy, but really, how do you get heavier than what a lot of people are doing? But I thought, Heaviness isn’t always in the sound, it can be in the attitude. So I realized that by creating these bends at the end of every phrase, you get a heaviness that’s like you’re being pulled down by gravity.

“Throughout the whole song, I had to figure out ways to do that bend-down quality, even in the solo. Double stops were the hardest; they’re very subtle. It’s very difficult to take two notes, bend them up a half-step, keep them in tune and then bend them down in the space of half a beat.

“The whole guitar is dropped down a whole step, and I used heavier strings. Even so, they were a little flappy. Playing this song was like bringing my fingers to the gym. [laughs] You’re lifting and pulling, lifting, pulling – and a lot of the notes were bent with one finger. It was a workout.”

Mullach A'tSi

“I’m a big fan of cultural music, and that’s how I try to expand my playing, by listening to music that is not conventionally American. The sensibilities of musicians can be so different from one country to another.

“I love Celtic music, and one of the CDs I have is called Celtic Lullabies. There’s a song on it called Mullach A’tSi. It’s a traditional Celtic lullaby, and I always found it incredibly transporting. The melody in and of itself is beautiful, but the way the singer performs it is absolutely exquisite.

“I thought, I have to do that. I want to do that on the guitar. I have to capture those beautiful nuances. I knew how I could replicate it – and all at once, I had an entire vision for it on the guitar.

“The first time I recorded the track, I basically copied the arrangement from the CD. It was very simple, but I wasn’t feeling it. It didn’t have enough variety. So I re-harmonized the whole song but kept the melody. When I was thinking of putting the band together, I wanted to do something a little different. I saw this woman, Deborah Henson-Conant, playing harp, and I was pretty stunned. She’s considered the hip harpist.

“I asked her if she wanted to join my band, and she said yes. We just finished three weeks of rehearsals – I knew it was going to be good, but I didn’t know it would be this good. She plays on the track, and she’s unbelievable.”

The Moon And I

“This song came from a soundcheck in Athens, Greece. I have this policy on tour where the band does their soundcheck, and then I come in. I don’t know what I’m going to play, but whatever I play, the band follows. We record what we do – sometimes it’s not very inspired, and other times you get something pretty nice.

“I remembered this soundcheck. We got about 15 seconds into the jam and these chords came out. I quickly explained to the band what to do because we didn’t have much time to play, but we ended up getting it down in one take. It sat on the shelf with about a hundred other soundchecks, but it was one of the ones I happened to go through. It moved me, I saw the potential in it, so I brushed it off, put the sound effects on it, put the vocals down and tweaked the guitar solo.

“It was released as a VaiTunes, but there was something very special to me about the track, and I didn’t want it to live in the digital-only world, so I remixed it and it became what it is.

“It’s a very personal song, actually. We go through a lot of emotional changes in life, and when I was a young man, between the ages of 20 and 22, I went through some real dark periods, a deep, deep kind of depression. I don’t even know why it happened. I wasn’t taking drugs, I had a great job, but you know, that stuff doesn’t matter.

“It got really bad, to the point where I was suicidal. I hit a real low one night, and right at the last moment, I had a feeling that this wasn’t going to solve anything; in fact, it was only going to make things much, much worse. And I was thinking to myself, Who’s telling me that? It was my first glimpse into the realization that there was more to life than just our identity.

“It was a miraculous moment, because from there my whole perspective started to change slowly, and I started to find some emotional equilibrium. After a year or so, I started to feel really good, and I’ve only been getting better and better and better. I’ve never ever gone back there.

“During those dark, low periods, I would have these dreams in which I was free of all that emotional chaos. I would see things that were very pleasing and beautiful… these landscapes of planets and stars. They were ethereal and colorful and profoundly beautiful. During these dreams, I was floating and surfing in the cosmos in a state of complete freedom. I wrote the lyrics to The Moon And I based on how I was feeling during those moments of euphoria and bliss.”

Weeping China Doll

“When you have a story that you apply to a song, it helps develop the atmosphere. With Weeping China Doll, I wanted something heavy but with a melody that was very sorrowful, and so I put myself in that emotional state in order to achieve what I was looking for.

“It’s interesting how I came up with the oddball parts. Outside my studio is a garden, and there’s a fence that surrounds it. My wife planted these roses called weeping china dolls along this fence, and they’re quite beautiful. When I would look at the roses against the fence, they kind of looked like music on manuscript paper. So I took photos of what I saw and transcribed it.

“Some of the melody is a reflection of the weeping china dolls on the fence outside my studio. It’s fun, you know? You can do whatever you want to make music. There’s no rules.

“For a while, I almost made it the seventh song on the album. It builds the way it builds, then breaks the way it breaks and goes into the solo, the hysteria. It seemed a little conventional for the seventh song. Mullach A’tSi has its own peak. The last bar of that song, to me, is the pinnacle moment of the album, just the way the melody comes out.

“Weeping China Doll has all of that intensity, but for me, it’s a little left of center in a way that didn’t qualify it for that seventh song."

Racing The World

“What happens a lot of times is, I’ll record an album, and then I’ll listen to it when I’m finished and try to decide what it needs to balance it out. With Passion And Warfare, I recorded the whole record, which took me years and years because of so much that was going on, and then I thought, OK, I need something else. I wrote The Animal in a day and a half. I wrote it, recorded it and mixed it.

“Same thing with Racing The World. I thought, Gosh, the record is so dense and intense at times... I need something simple that I can just play, where I won’t have to worry about knobs and wah-wahs and things like that – something that just gives you the melody on a silver platter.

“There a lot of people who want to just hear me do instrumental guitar stuff, and it’s hard to do an instrumental guitar record without sounding like Satriani. [laughs] He’s really got that covered. I’ve tried to avoid that my whole life, but then I just thought, Ah, just do it. There’s a lot of things I do that don’t sound like him at all, but every so often, you put a melody on a certain type of groove, and it’s going to smack of Satch. [laughs]

“It’s fine with me. We’re very different in many regards. I wanted a nice, easy, beautiful melody that’s fun to listen to. I was going to make the ending longer, actually. When I get to the finish line, I’m like a boxer – I punch and punch until I have nothing left.”

No More Amsterdam

“It was a riff that I had on my iPhone. I liked it and it kept coming back to me. Sometimes a riff has that spark; it’ll stay with you and shine brighter and brighter.

“I recorded the whole track. Conceptually, I wanted to hear all of these guitars. There’s probably 15 guitars on the song – jeez, more than that! Dozens of tracks with guitars, banjos, sitars, mandolins. Sometimes an instrument will come in a little bit here and there, but you can hear it; it makes an impact.

"I’ve known Aimee Mann for a while. We went to college together, and we actually lived a couple of doors away in the same apartment building. She was very good friends with my girlfriend at the time, Pia, who’s now my wife. Through the years, I was always exposed to Aimee’s music because Pia was buying it. There was something in it that really captured me, something very vulnerable yet confident.

“So when I wrote No More Amsterdam, I just had the track. I knew the song needed something, and I tried to write the lyrics, but I was having trouble. My wife said, ‘Why don’t you call Aimee?’

“My mind went through the same as it did with Beverly: ‘Ah, she probably just thinks I’m some shred wanker from the ‘80s.’ But I couldn’t have been more wrong. I sent Aimee the music and she really liked it. She didn’t even know what the word ‘shredder’ was. She thought it was the machine you put your mail and documents into. [laughs]

“It was a great experience. She came over, we connected really well, and hearing her voice coming through my microphone onto my song was such a powerful feeling. ‘Whoa, it’s really her – and it’s beautiful!’ [laughs] She did a great job of writing the lyrics. I was apprehensive about calling it No More Amsterdam because I didn’t want people to think it’s about kicking drugs or something. It’s not about that at all.

“My singing voice is very fragile and raw, and that’s the way that Aimee’s voice is, too. I love the way we sound together.”

“On this track, I used my Ibanez Euphoria and a Taylor 12-string. I also played a cavakino, which is this four-string instrument I bought in South America. And there’s the Coral sitar that I've used on virtually every record. A ton of electrics, too: I used a Tele on one side, a Strat on another. The heavy rhythms, which are kind of buried, that’s a relic’d Les Paul. There’s a lot of dimensions going on.”

Sunshine Electric Raindrops

“Another one I had on my iPhone. Sometimes these snippets are, like, five or six seconds long. This one was maybe 15 seconds, and it was that main [sings] ‘da-da-da-da-da-da-dahhhh.’ Part of me was pulling away from it because it sounded so pop – very pop. It was happy, but I was like, ‘It sounds too happy.’

“But I kept going back to it. Yes, it sounded corny, it sounded light, but something about it, I just liked it. [laughs] It’s carefree and it’s fun to play. So I thought, Don’t fight it. Record it. I gave it a big guitar sound with a lot of space. I’m really happy with it.

“I needed a certain flow to the body of the record, and I couldn’t hear this song fitting anywhere but at the end. It’s a cool way to take you out. It gives you a nice lift.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.