Stephen Stills looks out the window of his hotel suite in Short Hills, New Jersey, and dreams of bentgrass fairways. It's a clear blue sky outside, and the temperature is an easy-to-take 77 degrees. "Man, I should be playing golf on a day like this," he says.

Today's a show day - there's Carry On, Marrakesh Express, Almost Cut My Hair, Our House, Suite: Judy Blue Eyes, among others, and Crosby, Stills and Nash could easily triple the set with just as many biggies. The band members (along with their occasional fourth mate, Neil Young) are all Rock And Roll Hall Of Famers, twice each, in fact, when you consider their previous bands, The Byrds, The Hollies and Buffalo Springfield.

Throughout his career, Stills' guitar playing, a bold amalgam of folk, rock, blues, country and jazz has complemented (and sometimes eclipsed) some of the most astonishing recordings in the rock era. None of which is on Stills' mind as we sit down over coffee for a 90-minute conversation.

The 67-year-old musician admits that he finds the interview process a trying one. "But it's just that some of the questions I've gotten over the years have been so banal," he says, and if that's a not-so-thinly veiled warning, it's coming through loud and clear. Having said that, Stills takes a sip of coffee, settles back and asks, "Where do we begin?"

There's a new live CSN DVD and CD coming out, but will there be a new studio album soon?

"Well, there's the DVD, right, a live set. The thing's done, it's ready to go. But an album? We won't make another album, we won't finish one… [He sneezes, three times in a row.] Excuse me a second. [He gets up, goes into another room, sneezes three more times. Then he comes back in, shuts the window and sits back down.]

"Sorry. All the stuff that's coming in the window is making me sneeze. And there's a box set of my stuff coming. Here, wait… [He goes into another room, comes back and hands us four reference CDs.] My career.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

[Scanning the titles] Wow, this is incredible. There's so much material here - lots of unreleased stuff.

"That's right. It was supposed to be three discs, but I don't want to have to do it again, so I said just do four. That, along with Manassas: Pieces and Just Roll Tape, that pretty much covers it. There isn't much more left off that I care about. [Takes the first CD, looks at it.] There's a track on there, it was when I was about 16 or so. I was living in Costa Rica, so this is from the Voice Of America.

"I went to this guy's apartment, which was covered from wall to wall with tape recorders and listening stuff - way more than you need for a radio station.

"So he recorded me doing this thing. The song itself is absolute pabulum, but the guitar picking, it's fully formed, just like I do it now - the best way to spend an hour." [Laughs]

A couple of years ago, CSN were going to do a covers album with Rick Rubin. What happened with that?

"You should ask David. I was getting along fine. I'm not inferring anything, but I… I had an idea for 20 years of making the album we wish we'd written. We started picking songs and stuff.

"Some of the choices Rick made were pretty off the wall, but we tried them. We sang Uncle John's Band for an entire tour… and never really did understand what it was about! [Laughs]

"Rick has discovered physical fitness. It's brought him out of his shell. I'm pretty proud of him. When we were working together, I had just gone on a food thing of redoing everything, and so I was right in the middle of losing the 40 pounds I have lost."

You look good.

"I feel real good. I'm a little sore today."

You, David and Graham are involved in so many things. How do you decide when it's time to do CSN?

"Mahjong. Baccarat. We cut cards and read 'em. You know, there's no logical answer. And Neil, of course, is a force unto himself. The funny thing… we always thought CSNY would be the mothership, but in actuality, that would be CSN."

What was your first guitar? It was a Kay, wasn't it?

"Yeah. It was a Kay or a Harmony, one of the two. It could have been a Silvertone. One of the kids down the street had a four-string ukulele, and that's the first thing I played. I was about eight when I got my guitar.

"I also got a drum kit because my father despaired for the life of the furniture - see, I got my hands on drumsticks and played on anything."

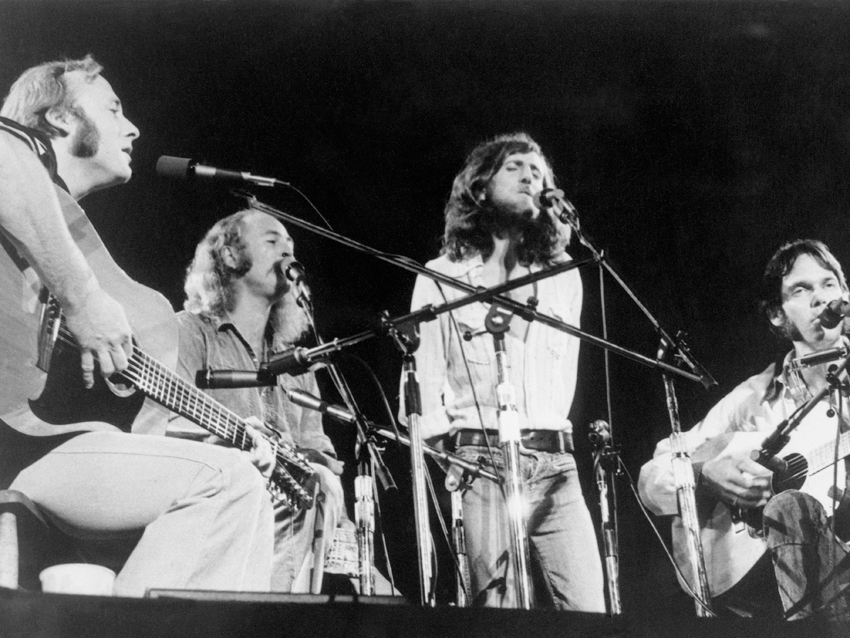

CSNY: (from left) Stills, Crosby, Nash and Young on stage in Seattle for their 1974 "reunion" tour. © Bettmann/CORBIS

When you really started getting into music, who were you listening to?

"Well, you know, it was harder back then. My dad played jazz on the Victrola. I heard Tommy Dorsey, Bob Crosby And The Bobcats… I'm probably still trying to get that same wonderful Dorsey tone on my guitar, that trombone sound."

How did you discover fingerpicking?

"It was around when I was first learning, and so Travis picking was what you did. My friend Mike Garcia and I would think nothing of driving 50 minutes to this record store that had old, used blues records.

"The Jimmy Reed stuff was the first stuff we learned because it was pretty easy. That was really great training, all the Arhoolie and Brunswick records, and Marshall Chess' early stuff. Great labels."

What was your first really good guitar?

"I think I had a Guild, and then I aspired to the Holy Grail, and that was a Martin. I finally got a Martin in the '60s in Greenwich Village. This was a really good Herringbone. I had to work part of that off in order to pay for it."

Let's talk about some of the guitars you've used through the years. There's the 1958 Gretsch White Falcon…

"Actually, I had an orange one before that. A friend took me to Tampa, Florida in 1959 to a demonstration at the local music shop, and we saw Chet Atkins.

"Right there, that began my love affair with Gretsches, because you can fingerpick 'em, particularly if you take the pickguard off. I've been doing that for a living for 50 years." [Laughs]

So you got the Chet Atkins model first…

"Now… see, you're testing my memory, which isn't good. Actually, I think I got my first Gretsch in the Springfield. Neil played one, which immediately attracted me to him. Anybody who played a Gretsch, that was it.

"But I liked the orange ones. Graham knows all the nomenclature. I like the brown ones, actually. I have two old, brown single cutaway Country Gentlemens, and they're really, really good.

"Now, the White Falcon in CSNY. Everybody was buying every guitar in sight. I happened to find a stereo White Falcon, and I traded Neil for his old one, which I still have. I've offered it back to him, but he says, 'No, no. A trade's a trade. You beat me on that one.'" [Laughs]

During the mid-'60s to early '70s, was there one particular amp you liked to pair Gretsches with?

"They sounded great through Marshalls. The only problem was they would feed back. But there's the blonde Fender Bassmans, you know, the brown-faced Bassmans… or a Twin. An older Twin, one with a presence switch on it."

Stills says he still wants to improve his guitar chops. "I'm getting there, although it's a little late." © Joe Bosso

When did you start getting into Firebirds?

"Later. I think Clapton got me into Firebirds. I found two that were just absolutely magnificent, but I had to put banjo pegs on them to keep them in tune. Getting them to stay in tune is hard, but once you do, they're welded, particularly if you don't have a whammy bar.

"You know, I don't know specific years. This is not the kind of arcane shit that I remember. I remember cars. [Laughs] I had a Ferrari when we first got money in the Buffalo Springfield. I got a Martin D-45 and a Ferrari."

You must have been making some real money.

"Back then I guess it was real money."

In Buffalo Springfield, how did you and Neil work out your guitar parts, your language together?

"By looking at each other and emulating each other. We'd copy each other, and by doing that we'd meet in the middle. He was much better than I was at first, although I had a better stroke for rhythm. But he was instrumental in teaching me how to play lead, showing me positions and stuff."

Around this time, you started using Fairchild Limiters on your guitars in the studio.

"Right. They made the guitar sound like a good, really big amp without taking over the whole track. You'd use the Fairchild and get lots of carry, so it sounded like a violin. Remember how I told you I liked the Tommy Dorsey trombone? You could do that on an electric.

"See, that was the age when we'd go into the studio like puppies. 'What happens when you turn this knob?' And the engineer would go, 'Aaahhhhh!' And then you'd go, 'Hey, it sounds OK!' I mean, we didn't break anything." [Laughs]

You've played so many different guitars during various phases in your career. Is there one right now that you would call your go-to guitar?

"Today it's a Strat. I've got two '54 Strats that I play live. They're lighter and they're easier on you. When you're just starting out, they can hurt. They hurt your fingers. But when you work with them and get used to them, they're the best. They're true everywhere, they're not cumbersome.

"I love my Super 400 and my Charlie Byrd, but they're cumbersome. I had a red Guild that was my first electric, but when I started playing lead I got a couple of really good Les Pauls - got a black one that I did all those records with. I had a Goldtop, but it grew feet in the late '70s. [laughs] Got boosted from the storage place."

Amp-wise, what are you using now?

"I've got a an old Bassman with four 10s, a Brownface Twin and a Vibrolux. I've just replaced my other Vibrolux with one of the Clapton models because it's got a lot more controls. It's new, and they gave it to me, so I liked the price." [Laughs]

What effects do you like?

"That's a secret. [Laughs] It's a box where things live. You know, it's a combination of things. I used to use an Eventide pitch control to broaden the sound, but they don't last that long on the road. I've stolen from the best. Echoplexes, they're pretty standard. I've got an old Fender Tube Reverb, and then I have a boost and a drive of indeterminate origin."

When you wrote For What It's Worth, did it start with that simple yet haunting two-note pattern?

"I'd been playing with the bass riff and was trying to connect something with the boys in the jungle, over in Nam, with the kids at home who were trying to get them home. I was living in Topanga and I came into town to go clubbing, and I came over Laurel Canyon, and right in Crescent Heights they were having a funeral for this bar called Pandora's Box. The place held 200 people, but there were at least 2000 people spilling out into the streets.

"The mayor of Los Angeles goes apeshit and says, 'Get those hippies off the street,' and they had just developed this tactic for riot control with the LA police. It freaked me completely out, and we turned the car around and I went home.

"Suddenly, the whole thing sparked in my head, the worlds came together, and the minute I got my hands on the guitar, I wrote the song. The whole thing was finished in 10 minutes.

"We made the record, and Neil came up with the wonderful harmonics part with the vibrato. The combination of the two guitar parts, with my scared little voice, that made the record. It really captured the 'What the fuck?' attitude.

"It seemed to speak to everyone. I got lots letters from the kids over there. They used to march in cadence to it."

What does that feel like? A song of yours that has such impact- and still does today.

"It feels… very satisfying. To have put my finger on something for even a brief second... yeah."

Let's talk about the Super Session record you did with Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.

"That was a complete fluke. I get a call from Al Kooper: 'I'm doing this jam session album, and Mike Bloomfield freaked out and split. I only have half an album. Can you come?' So I said I'd do it.

"I figured, if it didn't work, nobody would be none the wiser and it would be under the radar. But we did Season Of The Witch and it was spectacular."

A Strat-loving Stills on stage in Oakland, California, 2011. © William Mancebo/ZUMA Press/Corbis

That's an amazing version. It's very different from Donovan.

"That's imagination. I absorbed the song and said, 'Hey, this might go to that. Let's chase that for a while.'"

"Not much taller than me. A little wisp of a guy. Very soft spoken. I wouldn't be able to hear him today - my ears are so bad, even with these. [Points to a hearing aid in his right ear.] But he was funny, and he taught me a great deal about playing lead.

"I remember he was showing me something and I said, 'Jimi, Jimi... put your hand up.' So he held his hand up, and I put mine next to his, and I said, 'That's Wilt Chamberlin. This is me. Your thumb is longer than mine. I can't do what you're doing.' So he went, 'Oh yeah…' And he figured out a way to show me the same thing.

"Jimi was astonishing. Very dear, a dear soul. We'd decompress and talked for hours and hours."

You guys did a lot of jamming together.

"Yeah, but I went through it, and a lot of it is waiting for somebody to start something. It isn't really usable. It deteriorates into giggles and then the tape stops. I've been through it.

"There's a couple of things in there. Now that the family has worked their business out, I've done some of the things I did at Electric Lady with him. I've finished a couple of those. There's one song that's sitting there in want of a lyric - there's babbling but no good lyric."

Who was playing with you two at the time?

"Buddy Miles was playing with us one time, and then Mitch was playing one time. There was a nonsensical bass part that I replaced, and I'm also playing rhythm guitar. I don't know, we could just take guitar and drum and start screaming."

You mentioned that Jimi was showing you some things on the guitar. What specifically did you glean from him?

"You hear my playing, you should be able to figure that out. I channel him. I do that rarely, though - I just don't have the chops. I'm getting there, although it's a little late. I've already got carpal tunnel, so some of those things are a little hard to do." [Laughs]

Do you feel as though you're still getting better? What are you trying to improve on?

"Improve on? My stroke, my touch… chops. Chops! There's reach - that's chops. The ability to do… chops! How fast you can do it, and what your armature is like, what your stroke is like. Whether you can do it and dig in. What you can think of and what your physical ability is."

A Firebird-wielding Stills on stage with CSN, 1982. © Neal Preston/CORBIS

CSN vs Buffalo Springfield. CSN was definitely more vocal-oriented, wouldn't you say?

"Buffalo Springfield was more of a playing band. With CSN, the construction of the songs was such that we had to make room to stretch out. That English fellow had a wonderful effect on the construction, which is more in keeping with the folk songs. David's a jazzer, so things are more open-ended."

Your guitar sound on Wooden Ships is pretty spectacular.

"Barney Kessel. Barney Kessel and Les Paul, and then some of the guys I used to see at the Blue Note playing D'Angelicos. Something about that room made them echo."

Were you using flatwound strings on that song when you cut it?

"Yeah, yeah. That was a Super 400. The amp was… I think a Twin. No, no, it was one of my Brownface Bassmans. You've got eight knobs - four on the guitar and four on the amplifier. And the reverb. Good luck. Just keep messing with it and you'll find it. [Laughs] Put it this way: it was a complete freakin' accident. Everybody went, 'Stop! That sounds great.'"

The evolution of Suite: Judy Blue Eyes is interesting. On the demo that's on Just Roll Tape, it doesn't have the end part. How did it change when you cut it with CSN?

"That was an afterthought. We said, 'It needs something.' We sang that song for months before we recorded it, so it evolved. We were hanging together, Graham having made the leap of faith and singing everything we could think of. We let each other affect it."

The song Carry On from Déjà Vu - did that song come together all at once? It is broken down into two parts.

"It's more of a medley than a suite. It's interconnected songs. Again, it evolved. I had been thinking about it, and we had the album almost finished, and Graham said, 'We need another suite.'

"We were in the mind-meld, getting inside each other's heads. I think Questions might have been first, but I didn't realise they fit together until we started playing around."

Your soloing throughout is brilliant.

"I haven't heard it in a while."

But you play it live. Your solo changes night to night. You never play it note-for-note like it is on the record.

"You want to see that, go see the Eagles. [Laughs] I've always abhorred that. Unless you're playing an instrumental like Green Onions, you're supposed to improvise. That's the jazz cat in me."

Love The One You're With is featured in the movie Prometheus. Were you surprised at that?

"Yes, and I got a very nice cheque. I haven't seen it yet, I've just heard about it from my offspring. But apparently, it's there. Thank you, Ridley!" [Laughs]

Also on your first solo album, Eric Clapton played with you on Go Back Home. What was that experience like?

"He was a neighbour. I said, 'I need a solo, would you do one?' And he said, 'Yes, but only if you show me your acoustic guitar sound.' I said, 'Deal!' We did that and then we played Tequila all night long. That went for three hours."

And Jimi Hendrix played on Old Times, Good Times.

"Yeah. That was pretty quick. That was the song I needed to finish the album. We started doing something else, so we made some demos and then went out… never to return, unfortunately."

Where were you when you heard that he had died?

"I was in LA, and I was so fucking mad I almost broke the television. I threw something at the screen. I was furious. 'Cause assholes would keep giving him things, and he'd forget what he had taken."

When you played with Clapton and Hendrix, what guitars were you using?

"I was playing my Firebird. I found this really great white three-pickup one that had a beautiful high-end. Or I played a 12-string or I played bass. They played Strats. Eric had made the move to the Stratocaster. He warned me, 'You're going to get sick of all the switches. You'll find out!'" [Laughs]

Out tour these days, what songs do you particularly love playing from a guitar standpoint?

"Right now, I've discovered something new in Marrakesh Express. That just shows you how music stays alive, that you can always find something new. It's this new little deal, and it's really brought the band together. A little kick, you know? The song sounds hotter, fresh."

Throughout your history with CSN and CSNY, there have been some real ups and downs. Was there any one point when you thought it was over? That the bands might not continue?

"Actually, the downs are the only things the public cares about, because otherwise you don't have anything to talk about. [Laughs] At least twice a tour I thought it was over, but that's just us being brothers.

"In fact, I'm quite comfortable with them, and we've gotten much better at processing things. All the rest of it is none of your fucking business! [Laughs] As much as the fourth estate would like to make it their business, there's things that we couldn't possibly describe. They've been wonderfully cathartic, and they've been amazing growth experiences."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.