A-Z of folk music

From Acoustic to Zealots, an eclectic tribute to folk...

Acoustic

The arrival of the annual UK Cambridge Folk Festival (28-31 July) at Cherry Hinton Hall, and the Newport Folk Festival in the States (30-31 July) is a moment to pay tribute to a musical art form that underpins most of what we listen to today. July is folk month!

Folk is literally the root of most music. Nowadays, it’s a broad spectrum covering its oral tradition, but it also sits alongside country, soft rock, Celtic, rural, folk blues, gospel songs, zydeco, American, Appalachian ballads, mountain music, hillbilly wailers and agit-prop/protest.

Our A-Z confirms just how eclectic and open ended the folk cultural tradition has become…

A is for acoustic

Strings, soundboard and soundbox. That the acoustic guitar has been the kingpin instrument in the development of folk music, is to state the obvious.

A is also for The Almanac Singers

The Almanac Singers were, in the early 1940s, the most important US folk group. Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lee Hays and Millard Lampell caused controversy with left-wing songs but also kick-started a revival of trad-Am music. Songs like Hard, Ain’t It Hard; Round And Round Hitler’s Grave; The Strange Death Of John Doe; Talking Union and Which Side Are You On? inspired both Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen among others.

Listen: The Almanac Singers’ The Strange Death Of John Doe inspired Dylan’s Man On The Street

Joan Baez

B is for Joan Baez

The queen bee of (especially ‘60s) folk, she was also for a time influenced by and an influence upon the young Bob Dylan. In a songbook first published in 1964, songs she had already made famous were divided into ‘Lyrics and Laments’, ‘Child Ballads’, ‘Broadside Ballads’, ‘American Ballads’, ‘Hymns, Spirituals and Lullabies’ and ‘Composed Songs’. Categories which reinforced her - and folk’s - versatility.

Joan was described by John M Conly in his preface as “a beauty, as a person and vocally”. He thought she had two aspects. One, “her truly lucent voice, vital and lofting, with a timbre that is a resistless distillate of poignancy and thrill”. Two, “what she does with her humanity, a focus of feelings”. Through this extravagant gushing, it’s possible to recognise the awe in which she is held in music across the spectrum.

She said to The Sunday Times (UK) in 2006: “I quit writing songs a number of years ago, I had writer’s block. I’ve gone back very much to my roots musically. As it turns out, politically it’s absolutely the right thing to do”.

B is also for bluegrass music

Bluegrass is not folk, it’s American roots music. Some call it a cousin of country descending from English and Celtic immigrants to the US with jazz influences. It was described by Bill Monroe, bluegrass pioneer, as ‘Scottish bagpipes and ole-time fiddling, Methodist, Holiness, Baptist with a high lonesome sound’.

But it does touch the same roots and chords as pure folk, and channels much of the same old-fashioned, rural/industrial heartbreak, life and misery.

Listen (and watch): Joan Baez on the concert stage of political protests singing the old folk classic, Where Have All the Flowers Gone?

Celtic music

C is for Celtic music

‘Celtic’ is a generic term to describe Scottish, Irish and Welsh folk music, some of which paralleled pure English folk and most of which influenced the evolution of American folk. The term is understood as that by artists, producers and the paying public.

The Chieftains are a Celtic band, but with other genre influences and interpretations, the term folk may not be universally agreed. The Dubliners were possibly the first Irish folk-rock group, with a string of old rural Irish narrative numbers. They influenced The Pogues and Gaelic Storm among others.

Clannad, according to their official website, combined traditional strains ‘with a bold approach to writing and performing’. Their legacy ‘touches on folk, rock ambient, jazz and world music’.

Not to be left behind, there are several hundreds of Scottish folk groups and singers circuiting today. Almost all draw deep from the traditions of folk, but many now fuse elements of so many other genres, that contemporary folk’s boundaries must be redrawn somewhat.

C is also for Cajun & Creole

Just one strand of US folk music, creole is at least two hundred years old originating from the Deep South. Black creole is folk melody, sometimes dance related, often sung in French patois. Linked through roots with slave songs, it shows how ‘folk’ truly means ‘people’ and how musically, one generation leaves memories absorbed and re-invented by the next, as time/technology move forward.

C is also for clubs

From the late 1940s onwards, a handful of clubs, or regular gatherings of devotees of traditional music, established themselves in London and Birmingham. It’s thought that skiffle (late 1950s craze) filled a vacuum of the need to play versions of US jazz, blues and folk on acoustic and/or improvised instruments.

As American rock ‘n’ roll took off, a reaction set in and many clubs became bastions of traditional, often unaccompanied, music with solo voices. The regular attenders were frequently middle class/urban people, lauding a rural or industrialised working class.

By the mid ‘60s, many major population centres housed their own folk clubs (often little more than a back room in a pub), offering regular spots for home-grown talent and a circuit for rising performers, most famously Bunjies, Les Cousins and The Troubadour in London, and Troubadour in Bristol.

And C is also for Cambridge Folk Festival

The UK’s biggest folk event. Stemming from a 1964 request from Cambridge City Council to local firefighter and socialist political activist Ken Woollard to organise, it included the young and still relatively unknown Paul Simon as a late addition to the line-up. Folk was the voice of a nation or ethnic/geographic/economic/blood group.

Today, that it’s sponsored by the Co-op and Unison among others speaks to its folk, working-class traditional origins; the music of the people’s struggle against oppression, racism, poverty, class; the story of tragedies in mines, factories, ships, railroads: Morris dancing, guitars, gentle post-‘60s hippies with a radical edge.

Watch: Irish folk dancing, as in Lord Of The Dance is part of the same tradition as celtic folk music

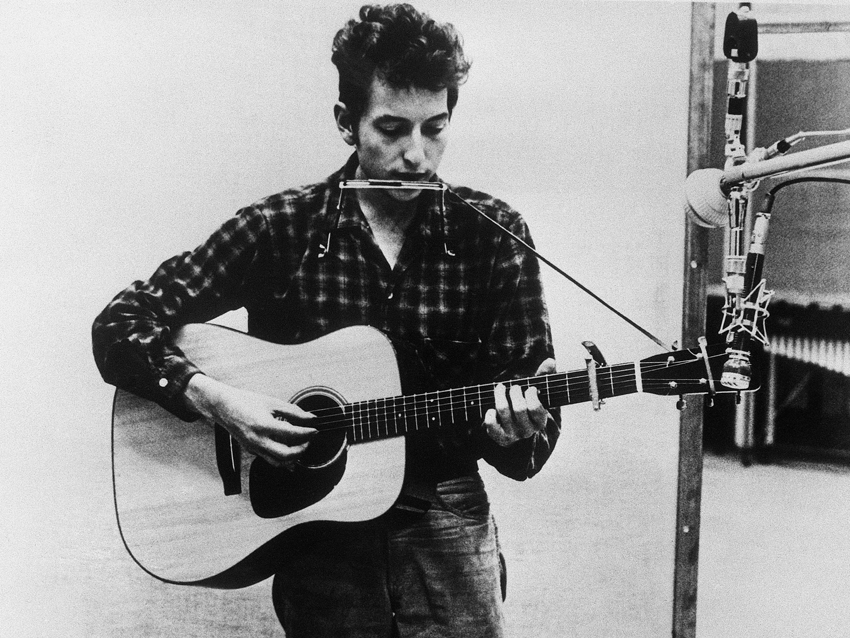

Bob Dylan

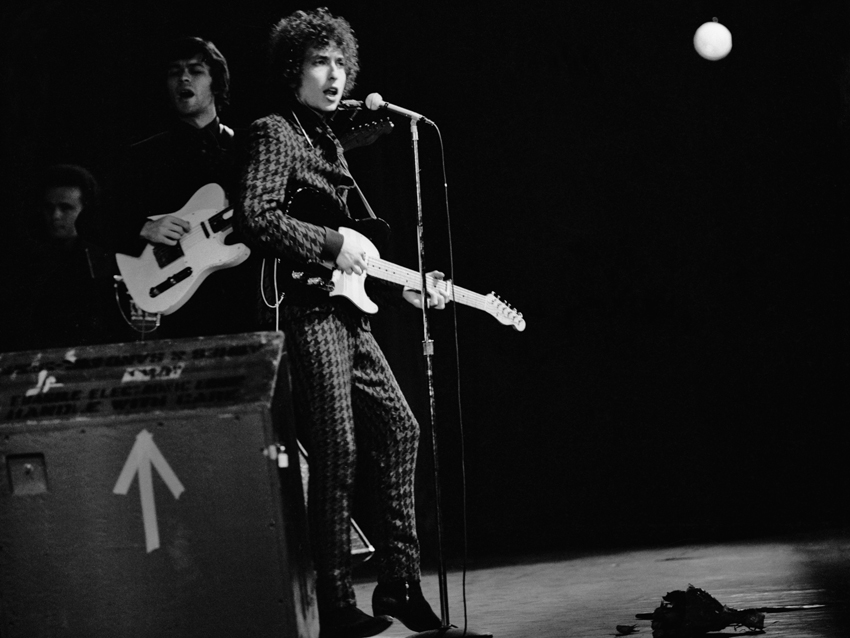

D is for Bob Dylan

Robert Zimmerman: poet; writer; singer; musician; and controversialist towering over all others in the 20th century, he has defined and redefined music over five decades, and is still doing it. His range is enormous from trad-folk to rock, from ballad to protest. He is studied in schools, colleges and universities by people learning about music and society.

His origins were in folk and blues, his writing about the down-trodden and abused, his Jewish-American background, his Christianity, his knack of putting to music love/anger/absurdity and his extraordinary ability to capture phrases and images that, as Bob Geldof said, ‘chime with the zeitgeist’, but also enter the international psyche.

He is, and always has been, the master of reinvention. Writing in Melody Maker in May 1966, Max Jones cried: “Will the real Bob Dylan please stand up?”

That has been echoed ever since, by critics, journalists and, to some extent, music fans. While simultaneously denying he was a protest singer, he told Jones: “All my songs are protest songs. All I do is protest. You name it, I’ll protest about it”.

At that point he considered Peter Lorre (the ‘sinister actor’, not a singer at all) the world’s greatest folk singer. This was all part of his developed sense of provoking journalists, of course, which adds to his mystery and in no way takes him from the top spot of musical influences of the 20th century. Read our A-Z of Bob Dylan here.

D is also for Donovan

Donovan Philips Leitch, an itinerant Scottish folk musician (singer/songwriter and guitarist), described by Adam Sweeting in The Daily Telegraph as the ‘universal pixie’, became for some people the British equivalent of Bob Dylan. His first single hit was Catch the Wind (1965) and he went on to create a string of hits as his style evolved blending elements of folk, pop, psychedelia and world music, including the anti-war ballad, Universal Soldier.

Donovan wrote in the UK’s Independent in 2005 about his first meeting with Dylan in a London hotel suite at the height of the media-led ‘Dylan vs Donovan controversy’, and it was recorded in Pennebaker’s movie Don’t Look Back. The fact is, that both men influenced each other to an extent, but were not enemies in any real sense. All part of the rich fabric of human life that is folk music in reality.

And D is also for Sandy Denny (1947-78)

English singer/songwriter who worked with The Strawbs and later the folk-rock band Fairport Convention as lead singer. She also toured the folk club circuits on her own and built up a dedicated following of her pure vocals. Her song Who Knows Where the Time Goes? has been covered widely by Eva Cassidy, Judy Collins, Lonnie Donegan, Nanci Griffith, Nina Simone and Barbara Dickson, among others.

Listen: Bob Dylan performing one of his songs about injustice, The Death Of Emmett Till

Ear (or rather, finger in the ear)

E is for ear, or rather finger in the ear

It was a fashionable technique among ‘60s folkies, variously to help hear themselves sing/find the right note against other noises around (like someone singing off-key nearby) or to look pretentious, depending on your point of view.

Some believed it added authenticity to a performer, much as how sticking a lit cigarette in the headstock of one’s guitar was supposed to add intensity and earnestness and imposed gravitas and credibility.

E is also for eclecticism

The mixing/fusing/blending of styles new and old has been a feature of artistic ventures forever, but musically it took off in the 1960s when Dylan, The Byrds, Joni Mitchell and other musicians began the experimenting.

Mixing traditional melodies, verse forms, ballads and narratives from folk music with rock, coupled with social, political and politico-social themes became not only the norm, but hugely commercially successful, and laid down paths that most others have followed since. Any definition of folk music today can only be described by including the concept of eclecticism.

John Martyn (1948-2009) was described by the UK’s Times as: “an electrifying guitarist and singer whose music blurred the boundaries between folk, jazz, rock and blues”.

To give just one contemporary example, Paul Russell admits on his website that he plays “eclectic acoustic folk music infused with elements of ragtime, country, jazz, tomfoolery, classical, celtic, delta blues and pirates.” Russell's influences include Martin Sexton, The Decemberists, Michael Hedges, Iron and Wine, Leonard Cohen, Nickel Creek, Darrell Scott, Keller Williams, Tom Robbins and Rob Brezsny.

Listen (and watch): Leonard Cohen inspiring eclecticism in others - The Stranger Song (live in 1967)

Festivals

F is for festivals

Around the world there are hundreds of folk-inspired gatherings. Here is just a sample:

From Canada (All Folked Up, Saskatchewan; ArtsWells, Bulkley Valley and Atlin in British Columbia; Apple Hollow in Quebec; Back to the Dirt; Brandon in Manitoba; several in Alberta; Ontario; Yukon; Nova Scotia; Yellowknife in Northwest Territories; New Brunswick).

From the US ( Alaska; American; Americana in Tennessee; Atlanta Michigan Bluegrass; San Francisco, San Diego and Grass Valley in California among several, including Culver City’s Festival of Dulcimers; Arizona; Boston; Vermont; Maryland; Fiddle Tunes in Washington; Chicago, River Revival among others in New York; Colorado; Cajun & Creole in Louisiana; Pennsylvania; North Carolina; Maine; Florida; Ohio; Massachusetts; Nevada; Virginia; Utah; Montana; Texas; Rhode Island; New Jersey; Connecticut and Alabama).

From Europe (Segovia, Ortigueira, Antequera Blues and others in Spain; Dublin, Cork, Quin and Celtic Fusions in Ireland; Buonalbergo in Italy; Belgium; Lorient in France; Prague and a Folk Festival of the European Broadcasting Union).

From UK (Abbey Mill in Wales; Bath Banjo; Ayrshire, Lanark Celtic, Bladnoch Folk & Blues and Orkney in Scotland; Durham Brass; Bolton; Cambridge; Crich Tramway in Derbyshire; Eastbourne; Beverley; Mid Cheshire Festival on trains; Suffolk’s Latitude; Birmingham’s Moseley; Stainsby; Shrewsbury; Scarborough; Southwell in Nottinghamshire and Wessex).

And not to forget the Afro-Cuban Folkloric one in Cuba.

Listen (and watch): Judy Collins and Joan Baez sing Baez’s Diamonds and Rust, Newport Folk Fest, 2009

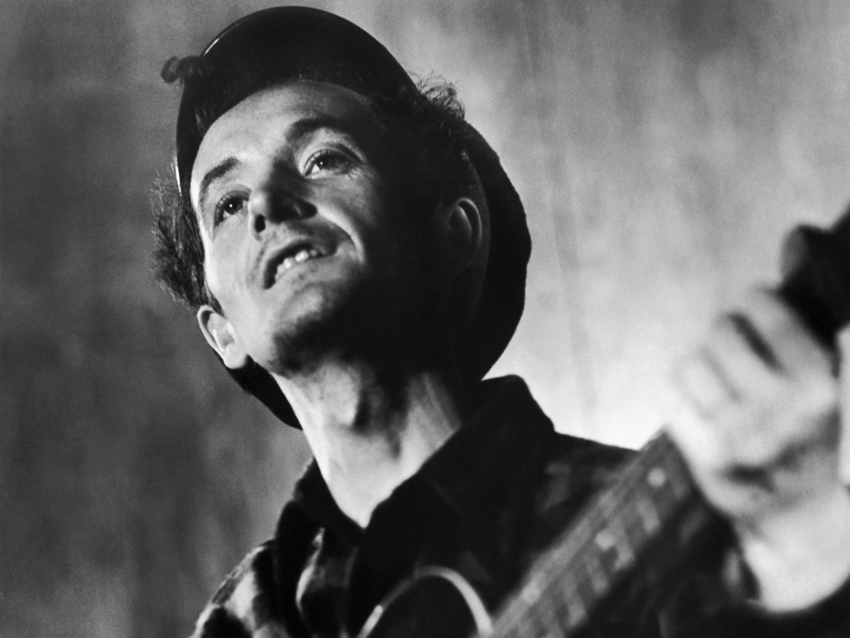

Woody Guthrie

G is for Woody Guthrie

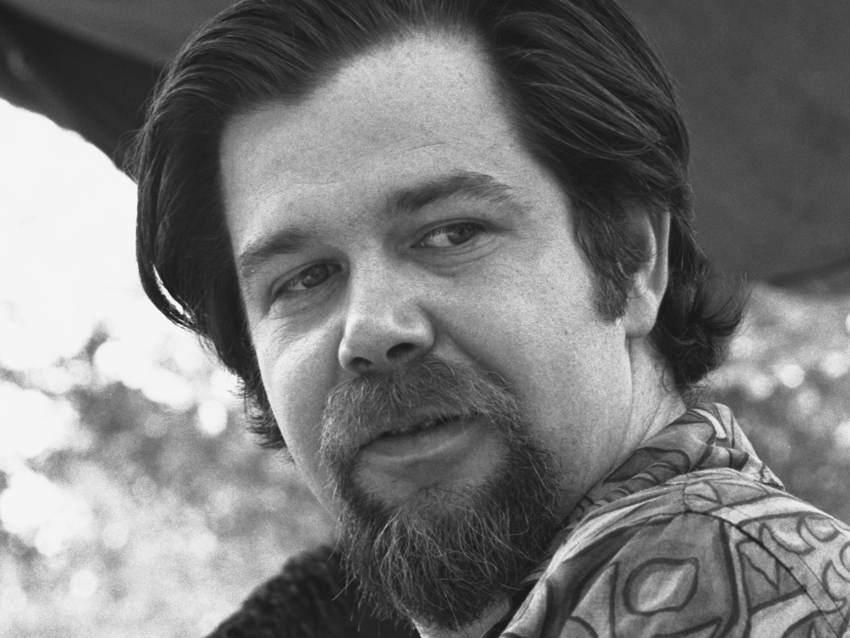

One of the great 20th century folkies whose influence continues and who epitomised the rural singer/writer highlighting the poverty and deprivation he encountered as he travelled around the USA in the 1920s and ‘30s, across dust bowls and dereliction, with perhaps his most famous an arrangement of the traditional (but also claimed as Carter family tune),This Land Is Your Land.

By the time he died from Huntingdon’s Chorea in 1967, he had seen his son Arlo Guthrie, Country Joe McDonald, Rambli’ Jack Elliott and Bob Dylan take up the folk/protest torch.

G is also for Guitar

The ultimate instrument of American folk. In fact, without an acoustic guitar in evidence, most would say, it’s not folk, though unaccompanied singing is part of the tradition.

Watch: Woody Guthrie’s son Arlo sings his dad’s classic, This Land Is Your Land

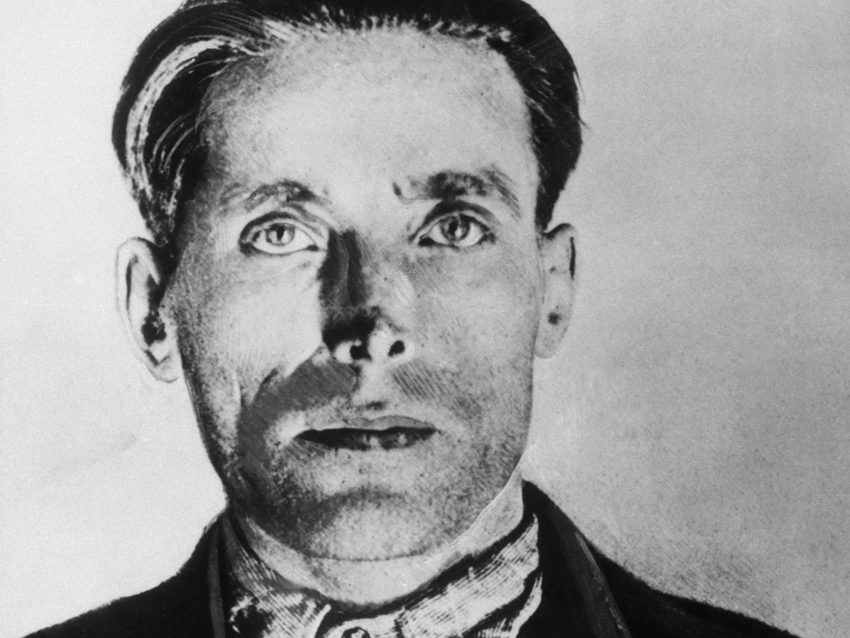

Joe Hill

H is for Joe Hill

Father of the US protest movement, (formerly Hillstrom, a Swedish immigrant to the US), who became a political activist after about 1910 having been in contact with ‘the underbelly of the labour market’, where the poor worked for a pittance. To buttress the Independent Workers of the World Movement he wrote songs repeated over and over and learned by heart, as many workers couldn’t read campaign literature.

The Expression ‘Pie in the Sky’ became absorbed into the language, after his song about food poverty: ‘you’ll get it when you die, pie in the sky’. He was executed by firing squad in 1915 by the State of Utah on what many thought was a trumped-up murder charge.

H is also for The Hawks

One of the former incarnations of The Band, Bob Dylan’s backing outfit in the mid ‘60s. They are interesting because they had worked from a rock ‘n’ roll and R&B background, and they collaborated with Dylan, who had become something of a colossus on the music scene. He had them playing electric adaptations of folk music, basically.

What it did, quite unintentionally, and being managed by Al Grossman too, was to enable The Band to evolve their own unique often raw sound that absorbed past and current atmospheres to make them big in their own right, with The Weight (1968) becoming a major hitsingle with some acclaimed albums too.

Listen (and watch): Joan Baez - I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night (Live at the Woodstock Festival, 1969)

Incredible String Band

I is for the Incredible String Band

Affectionately known as ISB, they were a psychedelic folk band originating in Scotland (variously Robin Williamson, Clive Palmer, Mike Heron and Licorice McKechnie), who built a range of dedicated followers from 1966 to the mid 1970s.

They were musical pioneers, admired by Bob Dylan, playing Newport Festival on a bill with Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen, integrating traditional music/folk forms with ever more instruments from the world music catalogue.

I is also for instruments

Of which there are almost enough to make an A-Z in their own right. Used in folk music besides guitars are accordian; autoharp; bagpipes; banjo; concertina; cymbals; dulcimer, bowed dulcimer and hammered dulcimer; African djembe; drum; fiddle, fiddle/violin and electric violin; flute; handclapping; harp; harmonica; hurdy-gurdy; jew’s or jaw harp; mandolin; pennywhistle; piano; ring flute; sitar, tambourine and washtub base. Not to forget the voice, from harmony to plainsong.

Listen (and watch): The Incredible String Band, 1968, The Half-Remarkable Question, playing some of their range of instruments

John Barleycorn

J is for John Barleycorn

The title of an old English folk tune. The man in the story is a personification of barley and the alcohol that can be made from it. The attacks, death, indignities and resurrection suffered by the man represent the reaping, malting and invigorating by drinking process.

It dates back to Pagan Saxon times going through many incarnations and versions subsequently. Scottish poet Robert Burns published his own version in 1782. In modern times, versions by Traffic, Bert Jansch, John Redbourne Group, Pentangle, Martin Carthy, Steeleye Span, Jethro Tull, Maddy Prior, Frank Black, Oysterband, Billy Bragg and Joe Walsh have kept the tradition alive.

J is also for Jongleur

J is also for Jongleur, which fits in folk, as some commentators believe, as it was originally a professional storyteller/reciter in medieval France, who combined music, juggling and acrobatics in the role. In that sense, it’s not hard to see the jongleur as the precursor of the folk musician.

English troubadour Ralph McTell (most famous for Streets Of London, 1968) was also for a time a busker, continuing the best tradition of the travelling folk minstrel.

Listen: Steeleye Span’s version of John Barleycorn

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in folk

K is for Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in folk

Given the organisation’s racial views over the years, it’s not surprising it should feature in the folk-protest area of music. A recent example is Greensboro Massacre by Bob A Feldman in the early 1980s, about ‘the massacre of 5 labor-movement activists at an anti-KKK rally in North Carolina, November 1979’.

The Klan is abbreviated KKK, which is not to be confused with the old folk song K-K-K-Katy. They sing often appropriated religious songs as their own anthems. Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit (1939) painted a comparison between fruit and rotting corpses of lynched black men hanging on trees; a folk song of protest.

K is also for The Kerrville Folk Festival

One of thousands, but unique in its focus on support and promotion for songwriters, writing, folk music education and live performances of trad-folk, bluegrass, acoustic rock, blues, country, jazz and Americana music.

A pair of celebratory Kerrville albums (25th anniversary and the early years) were produced by Tom Paxton, another of the big folk names. Over forty years of writing and singing have produced a huge range of songs for Seeger, The Weavers, Judy Collins, Sandy Denny, Baez, Doc Watson, Harry Belafonte, Peter Paul & Mary, Marianne Faithfull, and Willie Nelson among many.

His songs range from deeply profound to light comedy. He has touched on massacres, wars, injustices and short shelf-life numbers on temporarily topical issues such as financial meltdowns.

Listen: Folk-protest, with Bob A Feldman, 1980s

Legacy and labels

L is for legacy and labels

The legacy (that which we leave behind for the following generations) of folk music is impossible to quantify. The influence on later performers and songwriters, the political/social/cultural history of communities, countries and movements are deposited in folk music.

While many recording companies during the decades have issued folk music, one example is Folk-Legacy Records, founded by Sandy Paton, who died in 2009. He set it up as an independent record label specialising in traditional and contemporary folk music of the English-speaking world in 1961.

Regarded with affection by folk devotees, the label was acknowledged by Sing Out!’s editor Mark Moss as ‘hardly hi-tech’, but to pass on a legacy of such music it didn’t need to be. It had a love, dedication and vision that was unwavering. And that is what a legacy is; that is what folk music is.

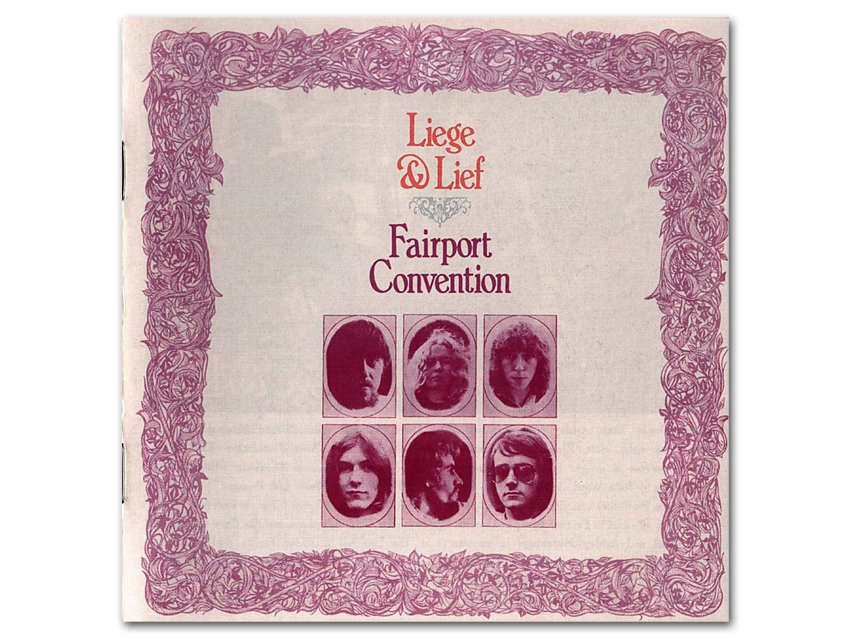

L is also for Liege & Lief

The 1969 seminal album from Fairport Convention. While recovering from a car crash that had killed their drummer and a friend, they researched traditional English folk songs and dances. Members, including Sandy Denny, debated the merits of various old songs and themes. The upshot was the album of which it was said, ‘folk-rock is born’.

In 2006, BBC Radio 2 listeners voted it the Most Influential Folk Album Of All Time.

What it did was to electrify jigs, ballads, myths and yarns with energy and skill. Fiddler Dave Swarbrick created an inspired partnership with guitarist-songwriter Richard Thompson.

Listen: Sandy Denny fronting Fairport Convention on Who Knows Where the Time Goes?

Most well-known or most-covered folk songs

M is for the most well-known or most-covered folk songs

Saved from oblivion by folklorist Alan Lomax, curator of the Archive of American Song, House of the Rising Sun (or Rising Sun Blues) is a folk-ballad variously thought to be about life gone bad in New Orleans or a London Soho brothel. It’s true origins are lost in the mists of time.

Probably first recorded in 1933 by Appalachian artists Clarence Ashley and Gwen Foster, it was a massive hit for The Animals in 1964, but other recordings combine to make it most known. Roy Acuff, Woody Guthrie, Josh White, Leadbelly, The Weavers, Frankie Laine, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk and Nina Simone have all recorded it.

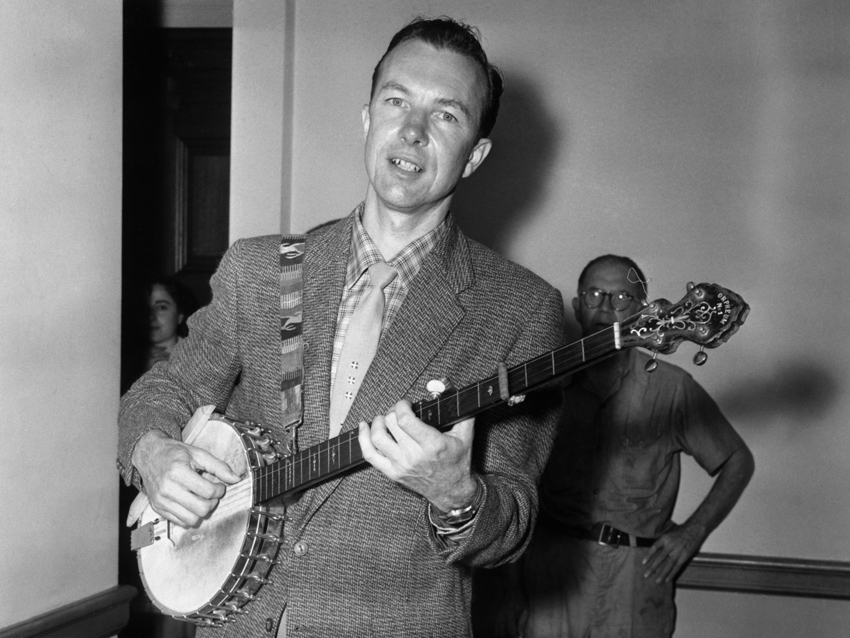

We Shall Overcome comes a close second in most well-known. It became the key anthem of 1960s American folk-protest in the civil rights movement. Adapted in 1947 by Pete Seeger from a negro spiritual melody (and The Sicilian Mariner’s Hymn from late Eighteenth Century) and performed by him and Joan Baez at rallies, festivals and concerts, it has since become associated with any struggle against insurmountable odds.

M is also for Ewan MacColl (1915-1989)

Ewan MacColl is an example of two things at least: one, the multiplicity of roles of people involved in folk (he was British folk singer, songwriter, socialist, actor, poet, playwright and record producer); and two, how people are often from extended families of like-minded people.

MacColl was in a long relationship with folk singer Peggy Seeger (sister to Pete Seeger); he was father of singer/songwriter Kirsty MacColl (The Smiths; The Pogues) and collaborated with socialist theatre director Joan Littlewood.

Just one of his songs, The Moving On Song, indicates the range of his political commitment through music and lyric. It’s about eviction and displacement.

And M is also for maritime and sea shanties

Maritime and sea shanties have long been a staple of the folk world for communities who live by the shore, and whose men endure the hardships of catching fish at sea in all weathers. Along with mining, factory and travel narratives, they constitute the bulk of folklore.

Listen (and watch): Ewan MacColl sings about his father in a political action traditional-style folk song

Newport Folk Festival

N is for Newport Folk Festival

Of all the gatherings, Newport, Rhode Island is probably the most iconic in folk and related musical history. Newport was founded by George Wein with Albert Grossman in 1959 on the back of his Newport Jazz Festival in 1954 and riding the tide of folk revival in the late 1950s, exemplified by The Kingston Trio’s Tom Dooley hitting number one in autumn 1958.

After launching Joan Baez, it changed to non-profit making, encouraged by Pete Seeger, into a vehicle to preserve folk. Passionate folk fan Murray Lerner started recording the growing event in 1963, stating: “I wanted to make a film about something bigger than music... an expression of the new culture”. That film, Festival, is part of musical history.

Dylan, Peter Paul & Mary, Donovan, The Jug Band, Blue Ridge Mountain Dancers, Judy Collins, Fiddler Beers, Mississippi John Hurt, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Mike Bloomfield, Johnny Cash, Richie Havens and Buffy Sainte-Marie are among acts that have helped make it such an event.

It has continued, harnessing cross-over and related contemporary genres beside folk, including alt-folk, indie folk and folk-punk!

Listen (and watch): Donovan showcases his folk and political credentials at Newport, 1965

Outrage

O is for outrage

The outrage that Dylan caused by going electric on 25 July 1965 at the Newport Folk Festival. This was his first appearance with an electric blues band in concert and it divided his fans.

Many felt he had betrayed his pure folk roots, and later in the UK, at the Manchester Free Trade Hall when he repeated it, the cry “Judas” can be heard loud and clear on the recording, from an outraged member of his audience. That controversy was only one of many in Dylan’s life, but significantly marked a rapid move into the fusion of folk, pop, country, rock.

O is also for Oscar Brand

Folk historian and folk champion, who over half a century provided a platform for folk’s great proponents. His website, modestly, describes him as: ‘Folk Singer, Recording Artist, Songwriter, Guitarist, Bawdy Song Balladeer, Sea Chantey Performer, Radio Broadcaster, Television Program Host, Special Events Director, Emcee, Broadway Musical Composer, Playwright, Actor, Author, Storyteller, Musicologist, Historian, Children's Recording Artist, Curator of the Songwriters Hall of Fame and Honorary Ph.D. He was also on the panel that created Sesame Street...’

He is also responsible for Laughing America (laughing through hard times), Ballads and Ballots (American political songs). Educational Awareness Month and Take Your Daughter to Work Day!

As Folksong Festival host over five decades on New York’s municipal radio station, WNYC, he fearlessly featured artists blacklisted as ‘commies’, from Guthrie, The Weavers, Leadbetter, Harry Belafonte, through Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Harry Chapin, Emmylou Harris and others.

Watch: Bob Dylan live at Newport Folk Festival, going electric

Politics

P is for politics

Ever since the early 20th Century, politics and folk music have been intertwined. As the labor movement grew in the early 20th century paralleling industrialisation, urbanisation, increased mechanisation and wars, songs advocating political, financial and social reform were born.

We Shall Overcome became linked to the civil rights movement in particular, but others such as Pete Seeger’s Where Have All the Flowers Gone? was anti-war protest song. Phil Ochs’ There But For Fortune was a protest on behalf of the innocent victim of prejudice. Many Dylan songs took on a politico-protest feel, besides Blowin’ in the Wind, such as Masters Of War, Oxford Town, With God On Our Side and Chimes Of Freedom..

People’s Music Network is a global network of musicians who play protest songs, the majority of which sing drawing on folk traditions and styles. British singer Billy Bragg, although usually described as an alternative rock musician and left-wing activist, draws heavily from the well of folk/protest to develop his material.

P is also for Pentangle

A relatively short-lived British band (1967-73), formed from inspiration by folk musicians Bert Jansch and John Renbourne. Stylish original material balanced material from folk’s heritage, their unique point was, as explained on their website, ‘delicate acoustic interplay between Jansch and Redbourne brilliantly underscored by Danny Thompson’s sympathetic support and Jacqui McShee’s soaring vocal intonation’.

And P is also for Peter, Paul and Mary

P is equally for Peter, Paul and Mary, (Peter Yarrow, Noel (Paul) Stookey and Mary Travers) who came together as the witch-hunting era of McCarthyism in the US died away.

Folk was being revived, while many still thought it a footnote to pop. But as the ‘60s dawned with its civil rights/Vietnam struggles, youth and flower power, socio-political arts taking off, the trio reclaimed folk’s potency, as their website affirms.

Listen: Pete Seeger singing the folk protest classic, We Shall Overcome

Quotes

Q is for quotes about folk music

Some shed real light on folk music itself. Some are funny; some profound.

- "All music is folk music. I ain't never heard a horse sing a song". (Louis Armstrong and Big Bill Broonzy)

- "At the same time all this was happening, there was a folk song revival movement going on, so the commercial music industry was actually changed by the Civil Rights Movement". (Bernice Johnson Reagon)

- "But in my imagination this whole thing developed and I started mixing up old folk songs with The Beatles’ beat and taking them down to Greenwich Village and playing them for the people there". (Roger McGuinn)

- "Everybody would grab a guitar and listen to somebody else and call themselves a folk singer. When they didn't know no more songs, they'd run out of them". (Brownie McGhee)

- "Folk is bare bones music". (Ben Harper)

- "Folk music was out there. Clubs were springing up and they were hot with the college kids”. (Dick Smothers)

- "Folk rock was my real roots. I did a few gigs as a folk artist, in the style of Fairport Convention". (Alan Parsons)

- "I always thought I was singing American folk music". (Lonnie Donegan)

- "I got hooked into folk music by accident, because that's what white college kids liked when I was a child". (Stephen Stills)

- "I knew Bobby Dylan back in the days when he lived in the village. He used to come and see me and sing songs for me, saying they ought to go into my next collected book on American folk music". (Alan Lomax)

- "I like narrative storytelling as being part of a tradition, a folk tradition". (Bruce Springsteen)

- "I wanted to write songs which I think is a different thing. I wanted to write music that is informed by folk music. The chord progressions are obvious references". (Joanna Newsom)

- "I'm just a very primitive, infantile folk singer". (Robert Wyatt)

- "It was really fun. Well, Bobby was just basically a folk singer. He didn't play with any bands or anything, like all the rest of us. Just played his guitar and sang his songs". (Barry McGuire)

- "Jazz is the folk music of the machine age". (Paul Whiteman)

- "Logically, when you talkin' about folk music and blues, you find out it's music of just plain people". (Brownie McGhee)

- "My idea of heaven is a place where the Tyne meets the Delta, where folk music meets the blues". (Mark Knopfler)

- "People thought me a bit strange at first; a blond haired, blue-eyed Norwegian who sang Mexican folk songs, but I used it to my advantage and got a job. And so the music became my ticket to education". (David Soul)

- "Real folk music long ago went to Nashville and left no known survivors". (Donal Henahan)

- "Skiffle was a name that was attached to what was, in essence, American folk music with a beat". (Van Morrison)

- "The big turning point, really, was The Beatles' influence on American folk music, and then Roger took it to the next step, and then along came The Lovin' Spoonful and everybody else". (Barry McGuire)

- "You have to open your mind. I like the ability to express myself in a deep way. It's the closest music to our humanity - it's like a folk music that rises up out of a culture". (Sonny Terry)

- "There are no bridges in folk songs because the peasants died building them". (Eugene Chadbourne)

Listen (and watch): Louis ‘All Music is Folk Music’ Armstrong - What A Wonderful World

Records

R is for records

Despite other forms of popular music distribution, companies producing records are very much part of the fabric of the genre of folk music.

Rounder Records is an independent folk/American roots label founded in 1970 in Cambridge, Massachusetts by college students. They describe their catalogue as a ‘roster who’s who of contemporary, traditional folk and roots music’.

Artists include Alison Krauss, Delta Spirit, Darol Anger, Doc Watson, Uncle Earl, Rhonda Vincent, The Steeldrivers, Madeleine Peyroux, King Wilkie, Siera Hull, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Bela Fleck, Nanci Griffith, The Cowboy Junkies and They Might Be Giants.

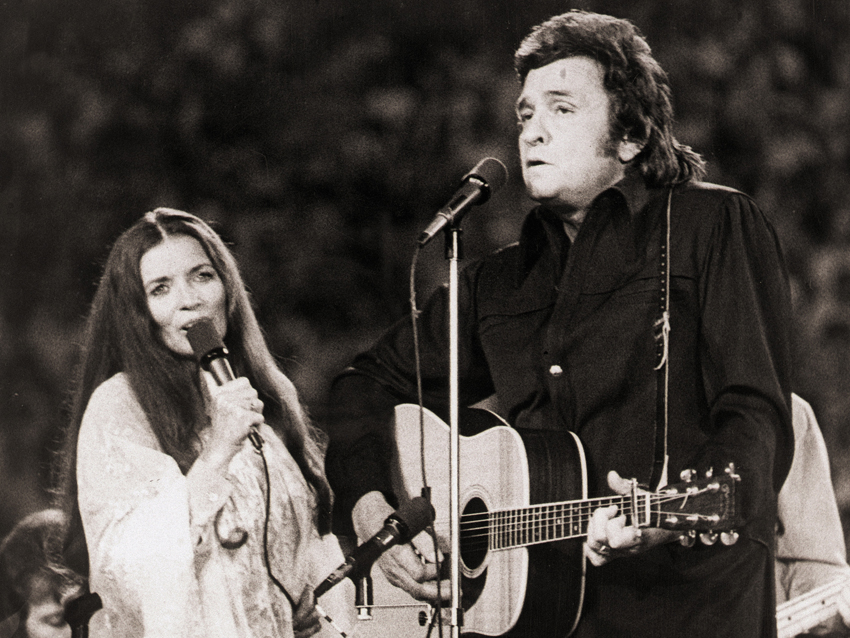

To take one example of folk artists who sold a lot of records, but were equally popular on the touring circuits: The Carter Family. They inspired Johnny Cash and Dylan. Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land melody probably came from an old Carter family tune. Their guitar picking style was unique: Maybelle played both rhythm and melody. It was album sales that financed their touring.

Eventually Maybelle’s daughter June, joined the band. She, of course, went on to marry Johnny Cash in 1968 and the song Ring Of Fire is one of several they wrote together.

Listen (and watch): Johnny Cash Live from San Quentin Prison

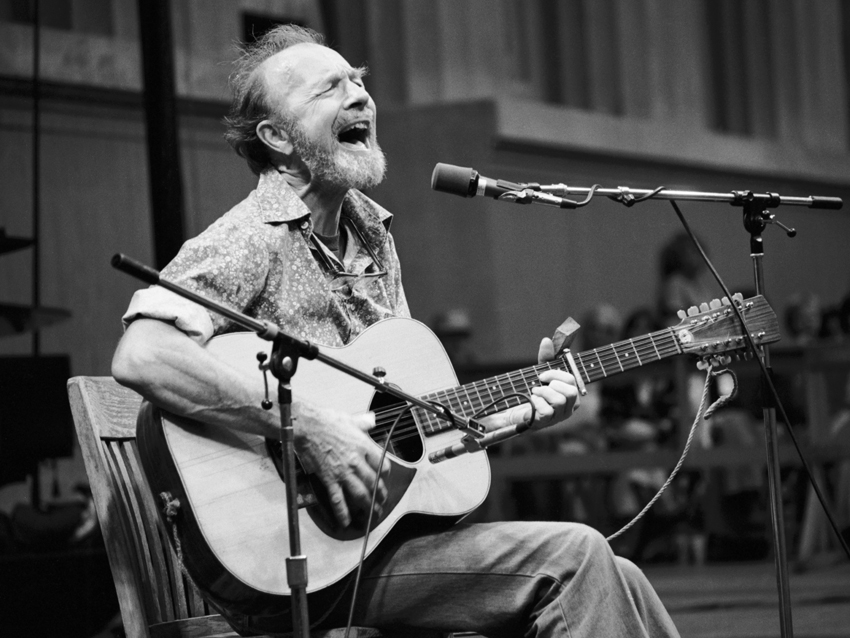

Pete Seeger

S is for Pete Seeger

Veteran of decades of folk music, Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame inductee, Harvard Arts medal winner, and Grammy Award winner for Best Traditional Folk Album (1996). US Library Of Congress named him a Living Legend in 2000. He is a national treasure of folk-lore.

Blacklisted in the USA’s McCarthy era of the 1950s when ‘reds under the beds’ were claimed to be a very real threat to the establishment, Seeger carried the torch of freedom for the labor movement, Civil Rights, peace and anti-war movements and environmentalism. He said; “Songs proliferate in prisons, they leap ethnic barriers”.

His biggest contribution to the civil rights movement was to adapt We Shall Overcome from a 19th century negro spiritual, and to make it the anthem of the protest movement.

Other, but less well known, folk-protest classics included Have You Been To Jail For Justice?, Dear Mr President and C For Conscription.

S is also for Spirituals and Anti-Slavery songs

Tunes like Go Down, Moses; Michael; Steal Away; He’s Just the Same Today; No More Auction Block; O Freedom; John Brown’s Body; The Abolitionist Hymn; Lincoln and Liberty and The Underground Railcar all came out of the suffering endured by American slaves, many influenced by The Bible, but almost all in turn, filtering down the musical line to influence folk songs that followed.

The singer Odetta (1930-2008) was one of the best-known folk artists of the ‘50s and ‘60s, influencing Dylan, Baez and Janis Joplin among artists, and Rosa Parks, the black woman who famously refused to give up her bus seat for a white passenger.

Odetta’s powerful voice espoused the civil rights cause, honed in the deep South against the Depression, prison songs and work field songs. For her ‘folk songs were the anger’.

And S is also for Steeleye Span

An English folk-rock band started in 1969 and still touring. Their biggest commercial successes were Gaudette and All Around My Hat. And lastly,Al Stewart, a Scottish singer-writer of the 1960s and ‘70s who developed his own style of combining folk with finely crafted stories of historical characters and events, and Year Of The Cat being his best-known.

Listen: Pete Seeger - We Shall Overcome

Theories

T is for theories

The movements of music genres, the cross-overs and fusions are always open to debate. One interesting theory was voiced by Martin Carthy on the BBC programme, Folk Britannia, when he claimed that Davy Graham, a highly rated virtuoso guitarist believed that there was a link between oriental music and Irish music.

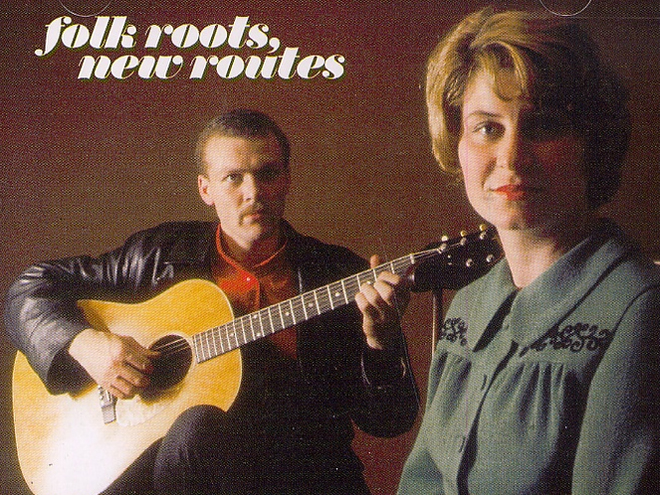

He demonstrated this by Graham’s rendition of the tune, She Moves Through The Fair, which he played on a guitar tuned to oriental music, and ‘he played melodically, rather than harmonically; chords were suggested, not imposed’.

Certainly, Graham did achieve an oriental, pentatonic-scale feel to the tune, so it may be that world music has always been closer, interlinked and threaded than people thought. He was also, with singer Shirley Collins responsible for Folk Roots New Routes (1964), a radical album that defined the crossroads of folk between its past and its future, fusing folk, jazz and blues.

T is also for Threads

It is also, then, for Threads. A party game is to be had in naming connections in folk and common ground. For example, how many songs include the line ‘I dreamed I saw...’ or similar?

The socialist activist and singer Joe Hill (see under H), was commemorated in a 1930 poem by Alfred Hayes, set to music by Earl Robinson (1936), and frequently performed by Pete Seeger, Paul Robeson and The Dubliners, I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night. Billy Bragg did a version, I Dreamed I Saw Phil Ochs Last Night.

This was lifted by Bob Dylan in his I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine. Country-folker Neil Halstead’s I Dreamed I Saw Soldiers goes in a different direction, as does Porter Wagoner’s I Dreamed I Saw America On Her Knees and Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush, which opens, ‘Well I dreamed I saw the knights in armor coming...’

American folk singer Ed McCurdy wrote, Last Night I Had The Strangest Dream, with the lyric: ‘Last night I had the strangest dream/I'd ever dreamed before/I dreamed the world had all agreed/To put an end to war’.

A Murder Of One by Counting Crows contains the line, ‘I dreamt I saw you walking up a hillside in the snow’. There is also Martin Luther King’s famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech and more recently, I Dreamed A Dream from the musical Les Miserables.

And so the Threads game can go on. It can be played with cover versions too. How many people recorded versions of Scarborough Fair, for example? Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Shirley Collins, Simon and Garfunkel, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, Sarah Brightman, Moody Blues’ singer Justin Hayward, Pentangle and Bryn Terfel.

Listen: Paul Robeson’s version of I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night

Underdog

U is for underdog

The core theme of so much folk music and its relatives down the years.

A 2010 project described by Judi Sawyer is her CD, Love For The Underdog. Inspired and encouraged at the US Kerrville Folk Festival by singer-songwriter Joe Jencks, she created an album in memory of ‘friend, father, pastor and mentor, Donald Miller’. It’s contemporary folk singing, but the theme of ‘underdog’ is a timeless one.

She signs off her reports on the project, ‘Peace Love And Folk Music’, neatly linking hippie nostalgia with contemporary hopes.

But pity, sympathy, understanding, vicarious suffering and help on behalf of the slaves, the orphans, the hungry, the falsely accused, the poor, the oppressed, the victims, the homeless, women/children, the lost/wandering and man’s inhumanity to man is as old as man’s sojourn on earth. It has been the staple diet of folk music.

Which Side Are You On? and I Pity The Poor Immigrant and Oh My Darlin‘ Clementine are just three typical examples of American underdog/tragedy songs. But other cultures have them too. Irish ‘lyric champion of the underdog’, Liam Weldon’s Dark Horse On the Wind is an ode and a lament for Ireland’s freedom. He uncompromisingly reflected major awareness of disadvantage, exploitation and poverty.

Goanna Dreaming (2010), an album by Shane Howard with fellow members of Goanna and some Aboriginal performers, is a series of melancholic songs expressing heart-felt concern for the environment and the underdog.

His anger at the squalor Aborigines were living in, his sense of sadness at visiting Uluru, their sacred site, and his outrage at how some native people were virtually enslaved in working for little without laws to protect them, led to his composing songs to highlight the issue for a largely white audience. Politics meets folk again.

This is echoed in anger leading to song about African slaves, native Americans, Jewish people and any other ethnic group maligned for years.

U is also for Ugly Boogie

An American folk music collective founded in 2010. Sporting clarinet, vocals, ukulele, guitar, bass, mandolin and drums, their sound utilises an eclectic array of acoustic and folk styles. That is the way modern folk is going.

Listen (and watch): Goanna - Solid Rock (1982), song about Aboriginal-indigenous land rights

Vashti Bunyan

V is for Vashti Bunyan

Recently rediscovered and hard to categorise, answering variously to folk, psych-folk and new folk. She was the typical solo girl singer, expelled from art school, travelling in the States, who encountered the Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was signed by Rolling Stones Manager Andrew Loog Oldham, and wrote lots of songs.

Travelling again, this time to the Hebrides by horse and cart, she wrote songs for what became the album Just Another Day. This was laid down in London with help from Robin Williamson of the ISB and Dave Swarbrick of Fairport Convention.

Disillusioned when it didn’t sell, she left music, raised a family, while unknown to her, the album became a cult hit. She returned. Her second album came 35 years after her first, along with tours, songs in advertisements and appearances. She now rejoices in the nickname, ‘The Godmother of Freak Folk’ for inspiring new folk experimentalists like Devendra Banhart and Adem.

V is also for Dave Van Ronk

Another unique voice in folk music, with a bit of political activism for good measure. Compared to his contemporaries (Dylan yet again), Doc Watson and Kris Kristofferson, he was a leading light in Greenwich Village folk-blues scene. There is a street named after him in New York, he refused to fly and Dylan talked about him in Chronicles.

He also talked about Eric ‘Rick’ Von Schmidt (1931-2007), a key part of the East Coast folk scene, Dylan’s friend during the early years.

Listen: Dave Van Ronk singing Cocaine in Greenwich Village

The working class

W is for the working class

The working class is regarded as the section of society for and about whom folk music arose.

W is also for The Weavers

Another short-lived US group (1948-52) who came after The Almanac Singers and Peter, Paul & Mary and Dylan. They fell foul of the blacklisting of artists deemed to be communist sympathisers, to produce work of traditional, often rural historical importance, blues/gospel/labor songs, to record and sing the heritage.

And W is also for world music

Almost every country on earth has its own folk music tradition, many of which do not employ the acoustic guitar. Any celebration of global music (Europe, US, Canada, S America, Africa, mid East, far East, Russia, India, Philippines...) would display the same sorts of cultural, historical, social, political, economic and psychological traits as anywhere else. It derives from people living life.

Womad - World of Music, Arts and Dance is an internationally established Festival which brings artist together in different locations, engages in educational projects and celebrates multiculturalism in the arts.

Peter Gabriel, as a founder said: “audiences gain insight into cultures other than their own”. That folk music with all its derivatives plays its part in world music, is a given nowadays.

Listen (and watch): Peter, Paul and Mary singing the Dylan’s classic Blowing In The Wind

Xylophone

X is for Xylophone

A percussion instrument, in which different length wooden bars are hit by hammers of wood, metal or rubber. They are tuned to different scale systems, depending on origin, including pentatonic, heptatonic, diatonic or chromatic.

Originating perhaps in Indonesia, China or even India, they were widespread in Europe since the Middle Ages, and were most associated with Eastern-European folk music, most noticeably from Poland and eastern Germany.

Sometimes they were called ‘straw fiddles’, when the bars were laid on straw. The 1523 painting by Holbein, Dance Of Death, depicts a skeleton playing a portable xylophone, since when it has symbolised the rattling of dried bones to many people.

A cousin of the instrument is the marimba, pitched an octave lower, and there are variations in Africa (including the log and gourd zylophones), India, Cuba and other parts. It is a quintessential piece of African folk music today, for its ability to express and carry rhythm.

The first orchestral piece composed for its use was Saint-Saens’ LeDanse Macabre (1875). It’s also closely related to the hammered dulcimer. One with metal bars is now called a metallaphone, and ones with tubular resonators are vibraphones.

X is also for Xanadu

A 6-man folk rock band, winners of Battle of the Bands, Tulsa, OK, 2006. It was an impressive instrumental combined with a unique lead singer’s voice that marked them out. The folk-rock genre they play in continues to expand, morph and evolve.

The Road to Xanadu are a UK folk-indie-psychedelic band, as yet unsigned, but with one self-released EP, with style rooted in traditional folk.

Yuletide

Y is for Yuletide

There are hundreds of folk songs that celebrate Christmas, and just one exemplar album is: American Folk Songs For Christmas, featuring tunes played by the Seeger family and Ewan MacColl.

Recommended as an antidote to excessive Christmas commercialism, it is homespun and warm and includes old numbers like Stars In The Heaven, Oh Watch The Stars, Rise Up Shepherd and Follow, Don’t You Hear The Lambs A-Crying, Look Away To Bethlehem, Jehovah Hallelujah, Joseph And Mary, Go Tell It On The Mountain, Star In The East, Cradle Hymn, Poor Little Jesus, Mariner’s Hymn and Singing In The Land.

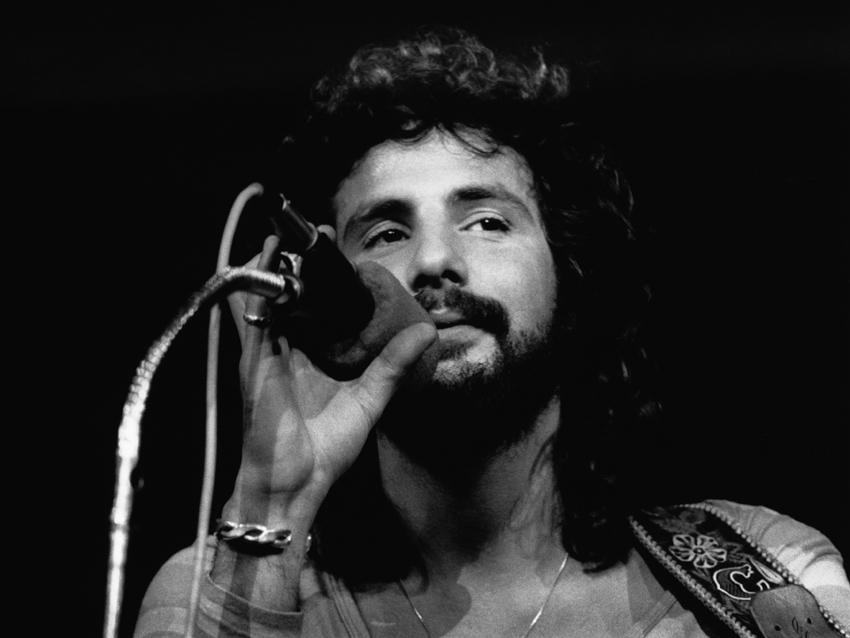

Y is also for Yusef Islam

Most famously known as Cat Stevens, one of the most influential song writers of the 1970s (comparable with Paul Simon, James Taylor, Don Maclean and Harry Chapin) combining classic pop with contemporary folk. Converting to Islam led to changing his name to Yusef, after Joseph, the interpreter of dreams, and his exit from the music scene.

And Y is also for The Yetties

An English folk music group more than 40 years in the business, named from their home Dorset village of Yetminster.

Listen (and watch): Cat Stevens (Yusef Islam) singing Wild World, his most covered song

Zeal and zealots

Z is for zeal and zealots

Zealots of folk music from trad-purists to new age folk-fusion fans, in tune with the musical zeitgeist! Long may they be remembered for what they have done to keep folk alive and prospering.

However, as we look to the future, today’s socially-conscious musicians utilise the internet besides older forms of traditional performance to get across their messages.

One example of a zealous contemporary folk band is 11-member, much-feted, Bellowhead. They mix traditional folky dance tunes with actual folk songs, shanties/ballads, and historical songs. A four-piece brass section with percussion and a rigorous style, they play over twenty instruments between them, and six supply vocals.

This versatility and range of genres within is typical of contemporary music and the way it is moving. They have also staged events/parties, such as an Abba-themed ceilidh, a circus-themed New Year’s Eve and named a new ale after their album, Hedonism!