"I have tremendous problems with some of my own tunes, unless they’re particularly simple": Remembering the musical mind, self-deprecation and wisdom of Allan Holdsworth

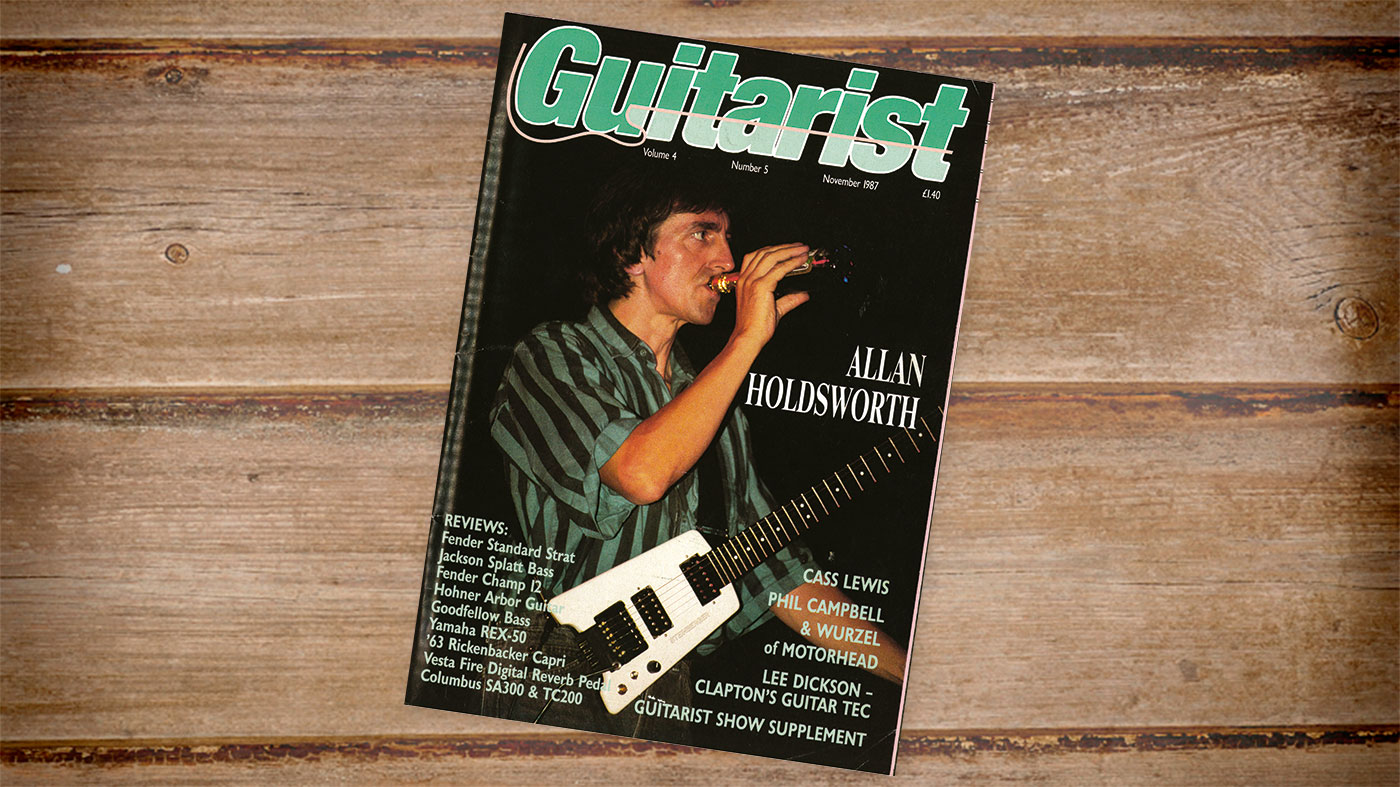

We go back to 1987 with one of guitar's true originals: "The basic major7 chord – the first one you probably learn on the guitar – is absolutely offensive to me"

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

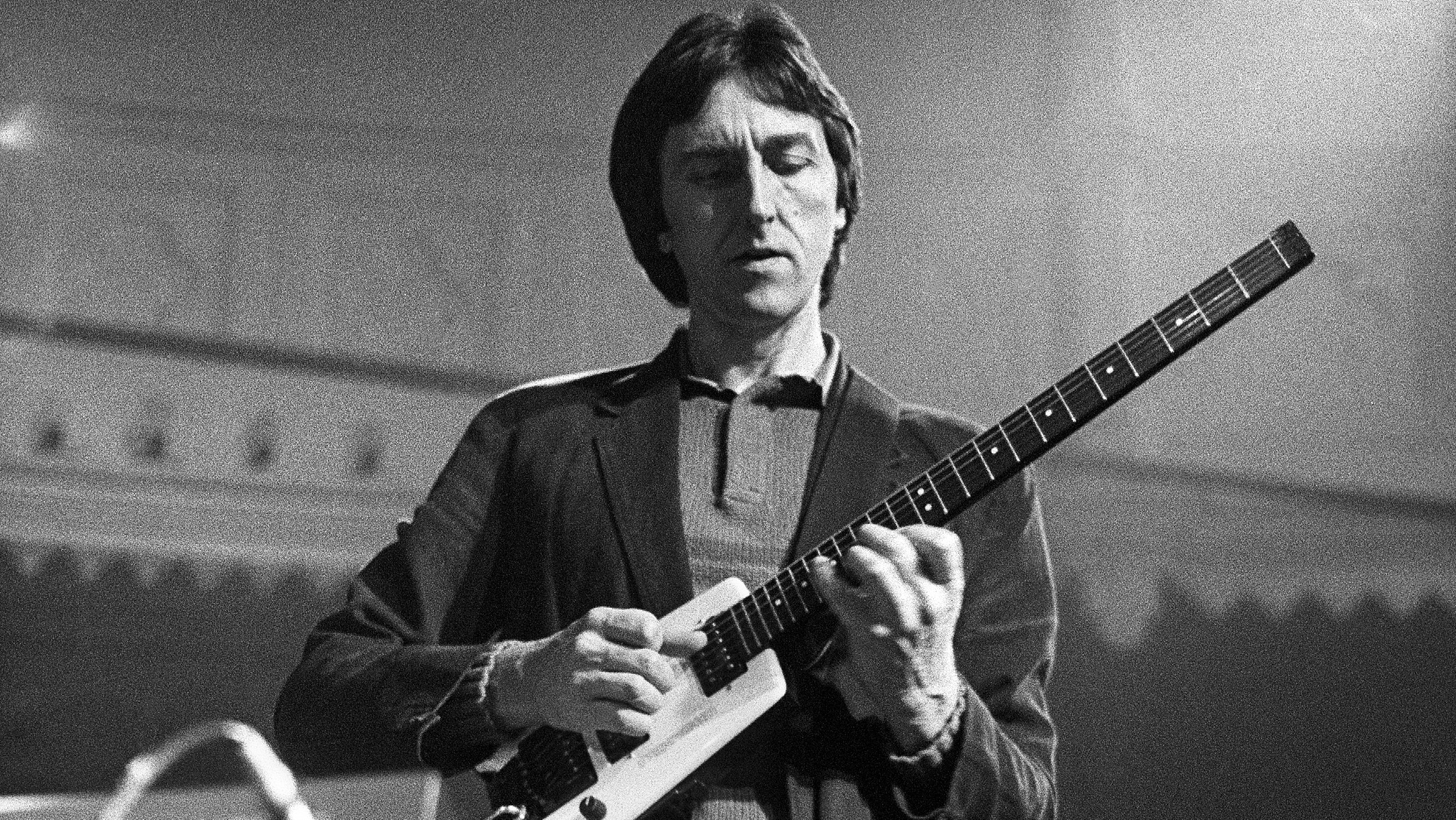

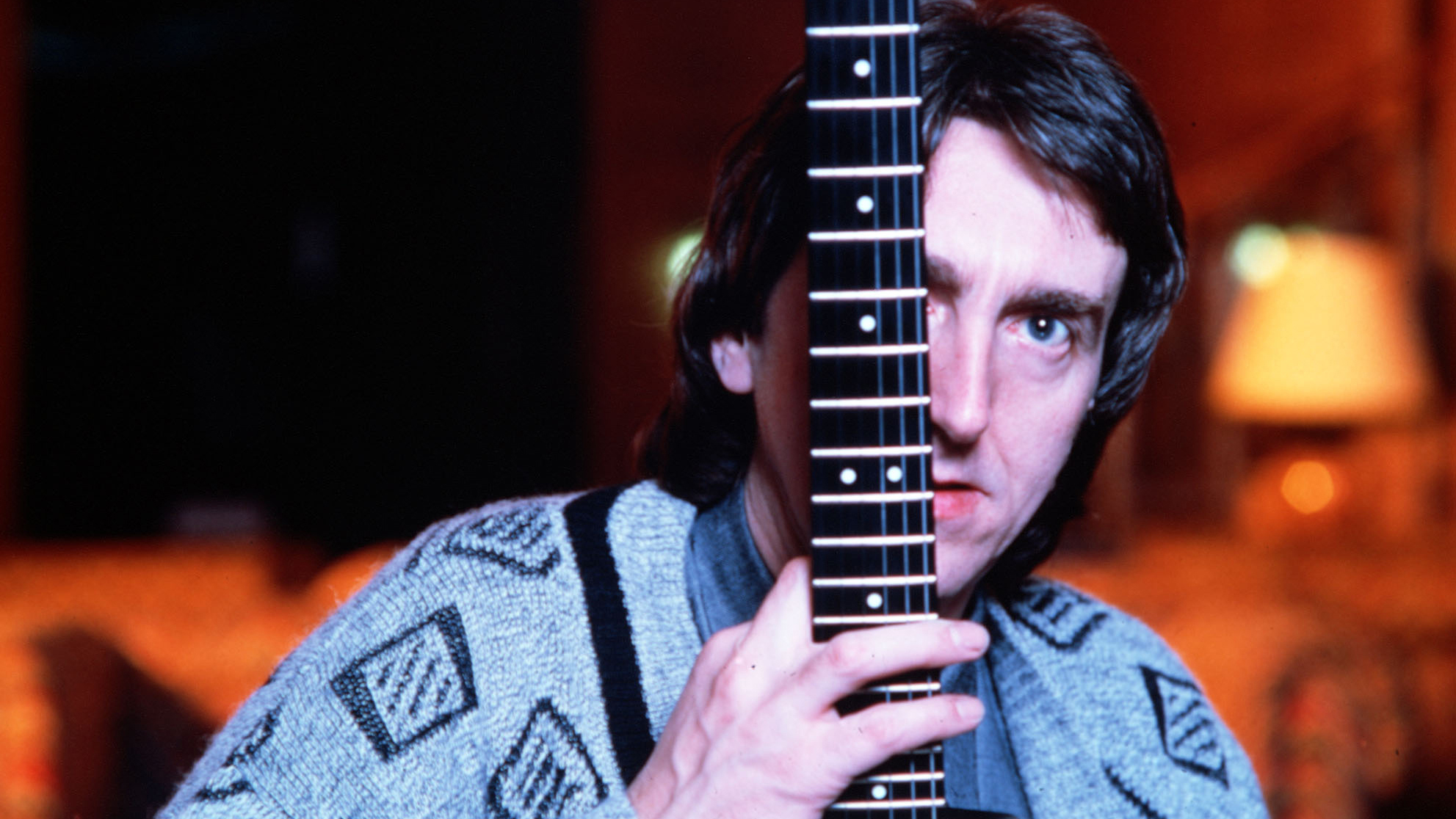

The terms ‘guitarist’s guitarist’ or ‘unsung hero’ are often bandied about in the music industry, but both pale into insignificance when it comes to the influence Allan Holdsworth had on the music of the last 45 years. Always working in the rarified area of jazz fusion, he never found commercial success.

“We can never get anybody - even in the States - to be interested in the music,” he told Neville Marten back in ’87. “I know people at various record companies and they’ll actually say to my manager, ‘Let me know when Allan decides to do something we can sell…’”

Unjustly, that uphill battle continued throughout his career but his legacy as one of the most original guitar players of all time is undeniable - a true great whose work will continue to inspire and challenge musicians.

In this cover story originally published in Guitarist magazine in 1987, Allan Holdsworth candidly revealed some of the inner workings of his unique approach to composing, recording and playing live. What emerges is a musician whose unflinching self-criticism pushed him to places no other player had been.

It’s just wire and magnets

“The electric guitar’s a pretty cheesy thing when you think about it, still working on those bits of wire and magnets for its sound. It’s all of the things that are wrong with it that have made it the unique instrument it is.

To me, I don’t see any difference between a synthesizer and an acoustic instrument. It’s what’s done on it that counts

“Because it still works by a vibrating string, it’s much more of an acoustic instrument than people would have given it credit for, initially. To me, I don’t see any difference between a synthesizer and an acoustic instrument. It’s what’s done on it that counts. If it’s a dog pile then it’s a dog pile, no matter what it’s done on.”

Thinking outside the box

“I made this box [the 'Harness'] that you just plug into the output of any amp. It has an output with a volume and a tone control on it. It’s a totally isolated output and it plugs into stereo processing or a mono power amp so you can control the volume from zero to whatever. And it captures all of the sound of the original amplifier.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“In fact, it sounds better to me. I’ve played it to quite a lot of people and every amp we’ve tried it with sounded better with the box than without it. It’s not like a power attenuator or a power soak as such, because that’s just like a load resistor and it also involves the speaker, whereas this has no speaker involvement at all.”

Thinking inside the box

“Any guitar player knows about trying to get a consistent sound in the studio. You can go in and move the speaker cabinet and the microphone around for a while and still not be happy with it, so I made a totally enclosed box that has the microphone and the speaker in it and you can change any of the speakers.

“The baffle slides in and out and I’ve got loads of different speakers I can put in it that I want to use for a specific sound. I’ve got a microphone inside the box on a rail, so it can move around and once you find something you like you just lock it there. So you just pick the box up and stick it in the car, plug the amp in at one end and plug the other end into the recording console - and you’re there!”

Panning for gold

“One guitar sound I was pretty pleased with was the one I used on 4.15 Bradford Executive. I used two amplifiers on that, a 50-watt Marshall and a 15-watt Gibson, and each of them was going into its respective ‘tweak’ box.

“I had the Marshall panned hard left and the Gibson panned hard right, and it worked out really good because each amplifier would reproduce different frequencies, slightly more or slightly less all the time, so you would get this nice fluctuation between left and right. It’s something I’ve never done before…”

Alight at the movies

I think if people could have seen visually what I meant, it would make a whole lot more sense

“I like to see something and then think of something that it conjures up musically. I’ve always done that. Most of the tunes have had some kind of meaning even though it hasn’t been overly apparent from the title.

“I think if people could have seen visually what I meant, it would make a whole lot more sense. Sometimes people have to see something visual to be able to relate to it and that’s why I would particularly like to get involved in writing for films. I’m sure some of it is tedious and I’m sure it would be really hard work, but it would be perfect because you could write something for one section and you’d never have to go back there again. I would really like that.”

No holds barred

It’s the notes that are the important thing. They’re the thing that are not transitory

“I see a whammy bar as being like the phase pedal - everybody’s got one now - but when I was looking for whammy bars on guitars in 1972, they all thought you were insane. Now you can’t even sell a guitar if it doesn’t have one on. So, to me, it’s a superficial thing, bound to have a fleeting use.

“It’s the notes that are the important thing. They’re the thing that are not transitory. It’s embarrassing when I listen back to how I used to play three or four years ago – it’s horrible. It’s absolutely horrendous and I can’t figure out what I was doing because it sounds so lame. Over the last few years, I’ve decided to place more emphasis on the sound and the notes rather than the ‘toy’ aspect of it - like a whammy bar or anything else.”

The power of four

“When I practice scales I will play four notes on one string. If I’m playing a C major scale, starting on F, I’ll play the F, G, A, and B on one string and the C will be on the A string, etc, etc. Because I found not only was it good for my hands but it was really good for interconnecting things.

“I didn’t want to end up playing in positions like you’d see guys playing, and every time it was a different chord their hand would be in a completely different position, and I wanted to eliminate that completely. So I always practiced playing scales in every position and I looked at four notes per string as a way of connecting positions together.”

Achieving a pure legato

“I never use pull-offs because I don’t like the sort of ‘meow’ sound they make with the string being deflected sideways. So I kind of tap the finger on and lift it directly off the string. I practise trying to make all the notes play the same volume or even some of the notes I’ve hammered, louder than the notes I’ve picked. So you can place an accent anywhere you normally would if you were using a pick.

“I’ve got better at it now and when I listen to it I can pick up what’s going on and I think it’s harder to tell now what’s picked and what isn’t. But basically I wanted to make a note I’d hammered louder than a note I’d picked.”

Immersed in inversions

I just started experimenting by taking three or four notes and I’d take a triad and go through all the inversions I could get on the lower three strings

“The basic major7 chord - the first one you probably learn on the guitar - is absolutely offensive to me. It’s horrible and I’ve always felt that about chords even before I started playing and knew what they were.

“I’d hear a certain chord and go, ‘Yuck!’ So because of this, I just started experimenting by taking three or four notes and I’d take a triad and go through all the inversions I could get on the lower three strings, then do the same on the next three, and so on.

“Then I’d take a four-note chord and do the same thing, and then I’d take a five-note chord and so on. Obviously, when you get to six-note chords there are not too many six-note chords for guitar…”

The altered state

“I don’t like altered dominant chords. I don’t like the way they sound and, obviously, there are more of them than any other type of chord, so I always try to substitute them or put the notes in an order where the sound you hear isn’t so easily recognisable as just a nasty old altered dominant chord.

“Of course, that gets hard on a guitar because of all the notes that should be in it - there’s quite a lot and it’s not that easy to play that amount. So if someone shouts out a particular chord, I might not play a chord that has any of the necessary relevant notes in it, but it will have all or some of the relevant notes that are in that scale in it. That was something I noticed piano players did all the time and which guitar players didn’t do very much.”

Soloing on this stuff is hard!

“You’d assume that because I’ve written the thing it would be easier for me [to solo over it], but it’s not. In actual fact, some of the tunes that I’ve written I find incredibly difficult to solo over, and sometimes I have to sit down for a long time. Because it’s one thing to harmonically create something and it’s another thing to blow like crazy over it.

I have tremendous problems soloing over some of my own tunes, unless they’re particularly simple

“So I have tremendous problems with some of my own tunes, unless they’re particularly simple. I like to put chords in orders that they wouldn’t necessarily come in and I’ve seen other guys have a little bit of trouble with them, so that always makes me feel a lot better.”

Sounds lame? Make it better

“Sometimes [I practise] a lot, sometimes not. I don’t have a set schedule, but I usually end up playing at least once a day. Generally, if I come back off the road I’m too wasted to do anything. But at the same time I always come back feeling really disappointed in my performance and look to make the things I did that sounded lame, sound better.

I’d say about once or twice a year I have a gig I think was okay and they’re usually those gigs where it almost feels like something else took over

“I get scared when anything happens that I liked; I think, ‘What went wrong?’ I’d say about once or twice a year I have a gig I think was okay and they’re usually those gigs where it almost feels like something else took over. But, generally, it feels like I’m labouring like crazy over it and can’t make sense out of anything and I end up playing a load of crud.”

My own worst critic

“I record gig tapes from two or three tours ago and listen to them and get a truer perspective of what’s happening. When I listen to them after the gig, I hate them because you are really close to it and you know what you were trying to do. You know what happened and what didn’t happen, but six months or a year later you’ve kind of forgotten what you were trying to do on a specific gig and you can listen to it from outside it.

“It’s surprising sometimes: something I thought was really horrible doesn’t sound as horrible and vice versa, something that I thought was quite a good gig can sound horrendous!”