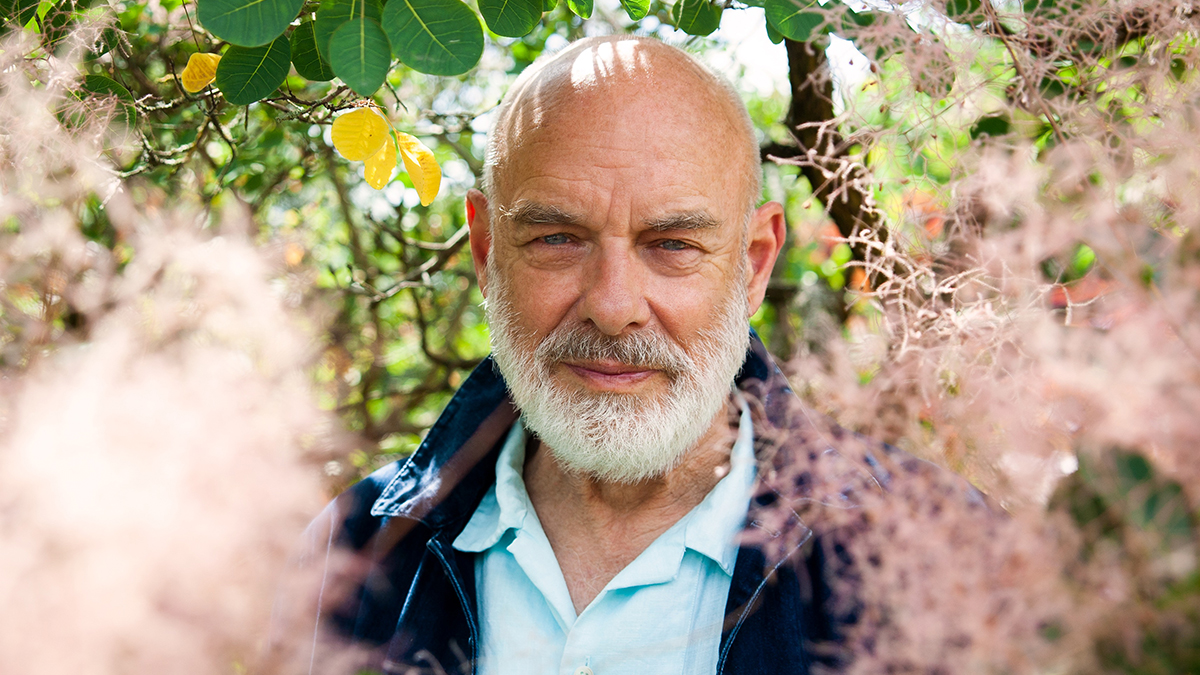

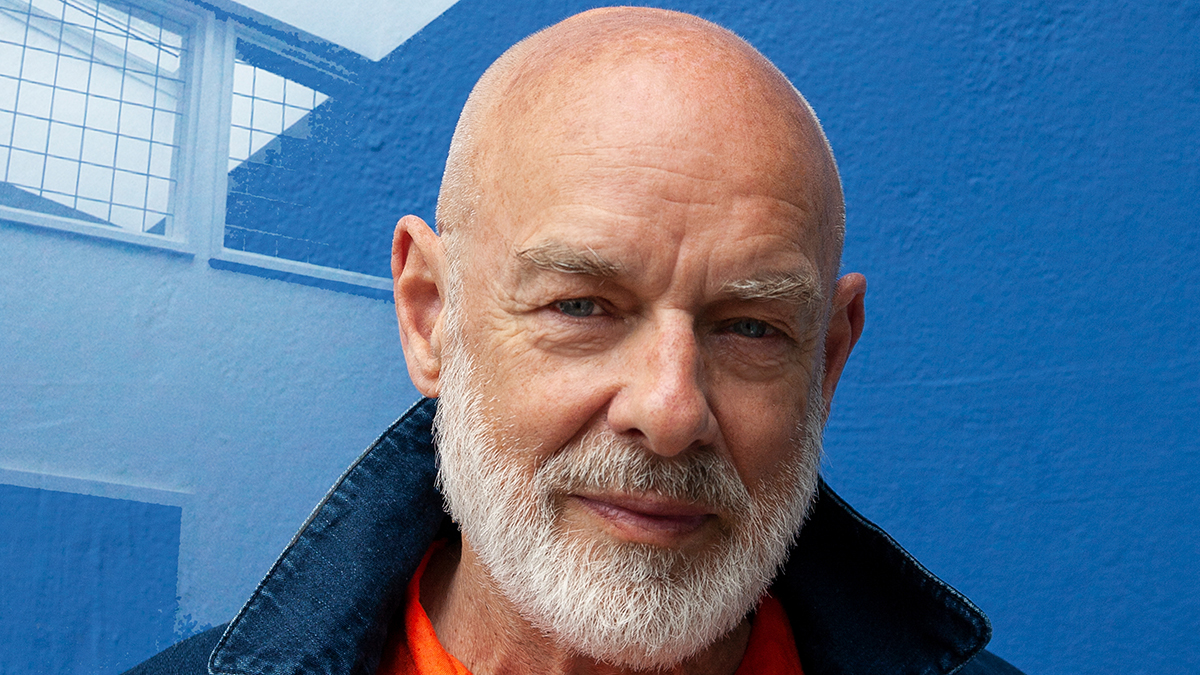

“Beginnings are easy - endings are hard”: Brian Eno speaks for music producers everywhere as he discusses the “terror” of trying not to ruin a good idea

“Everything you try on it makes it worse, and yet you know it’s not finished”

Although there’s always that risk that you’ll suffer from ‘empty arrange page syndrome’ when you first open your DAW, for many of us, the ‘ideas stage’ of music production can often be the most rewarding. You’re in thrall to that moment of inspiration, and the freedom that comes with being able to explore it, but the creative process frequently becomes more difficult as you try and develop the idea and turn it into a finished track.

It’s comforting to learn, then, that even world-famous artists such as Brian Eno recognise this problem.

The revelation came when Eno spoke to Zane Lowe on Apple Music about the making of his new album, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE. “Beginnings are easy - endings are hard,” he admitted. “There’s so much technological assistance to beginnings - so many ways of getting started - like rhythm machines and chord pattern makers and all that sort of thing.

“So there’s lots of ways of getting something pretty respectable going quite early on.”

Eno went on to quote Picasso, who once said that ‘There’s nothing worse than a brilliant beginning’. The implication being, of course, that the risk is that it’ll be all downhill after that.

Eno describes “that feeling of terror you get when you’ve done something and you know it’s good, and you just don’t know how not to ruin it. Everything you try on it makes it worse, and yet you know it’s not finished”

Lowe also spoke to Eno about his mentorship of super-hot producer Fred Again (AKA Fred Gibson), who he met when Gibson joined an acapella group at his London studio when he was just 16. Fred collaborated with Eno and Underworld man Karl Hyde on their two 2014 albums, and has gone on to work with everyone from George Ezra and Rita Ora to Skrillex and Swedish House Mafia.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I think of Fred as my mentor as well,” says Eno. “I learnt so much about contemporary music from watching him working.

“When I first worked with Fred I could see he was brilliant… but I didn’t really understand a lot of what he was doing. It took me quite a while to think ‘Oh my gosh, this is really a new idea about how you can make music.’”

“So I learnt a lot from him. It’s a two-way relationship. I’m very flattered to be called a mentor of someone whose work I like a lot, but actually, it worked both ways round. I started listening to music differently when I watched how Fred was making it.”

Asked by Lowe to expand on how Fred’s process is different to his own, Eno said: “It’s very common if you’re working with Logic or any of these other kinds of programs [DAWs] that you kind of get a loop going, and that’s the sort of groundwork, and then you start putting things on top of it. And it’s quite a linear building process.

“What I noticed with Fred is that he would start something, and he wouldn’t turn it into a loop that’s going to run through the whole track. He’d just have it running for a tiny little bit and then he’d put something else there, and then suddenly there would be a big hole and there would be a disruption.

“They’re very non-linear, his pieces - they don’t have the same homogeneity that you would normally get from, for instance, loop-based music.”

Eno also became fascinated by the way in which Fred sources his sounds, and how this influences his productions right the way through to completion.

“He’s often recording on his phone, and he’s often recording in quite noisy places,” Eno explains. “And he doesn’t clean everything off, so in every piece of recording there’s a sort of context that comes with it as well. The sound has a history built into it.”

Brian Eno’s new album, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE, is available now.

I’m the Deputy Editor of MusicRadar, having worked on the site since its launch in 2007. I previously spent eight years working on our sister magazine, Computer Music. I’ve been playing the piano, gigging in bands and failing to finish tracks at home for more than 30 years, 24 of which I’ve also spent writing about music and the ever-changing technology used to make it.