"I think our roots are also in '70s and '80s rock, the beginning of progressive rock, and the beginning of electro music: Joe Duplantier on the combination and ideology that makes Gojira's vision of metal so special

In this 2021 interview the Gojira frontman and guitarist talked volume, gear and the push/pull between the principles of the old-school and new

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Gojira were formed in 1996, then under the name Godzilla before adopting the Japanese name for its most famous city-levelling kaiju in 2001, they quickly set about rearranging extreme metal’s physiology.

Here were four kids from Bayonne, France, with a big-hitting drummer and a sui generis electric guitar style that took the grandeur of mid-80s Metallica, the animalistic chaos engine of '90s death metal, Meshuggah’s internal clock and the restless curiosity of progressive rock, and exposed it to all the kinetic dynamics of creative destruction.

This new sound Gojira were debuting had familiar qualities, and cultural touchstones encoded in its DNA, and yet it was unrecognisable from anything that had gone before. It was the weirdest thing.

There are many traditions that we need to reinvent, many of the ways we conduct ourselves that we need to better, and to challenge, if we are to make it as a species

For metal fans who grew up consuming the same influences as the brother Joe and Mario Duplantier – Joe the senior by four-and-a-bit years – this was fresh, exhilarating, surreal, like watching an evolutionary step in real-time, as though we were a prehistoric people watching a dinosaur assume the form of a crow.

That analogy might be heavy on the anachronism but then so are Gojira. There’s something old-school about their new-school approach to metal, and this duality is typified by guitarist and frontman Joe Duplantier.

He’s the guy who rerouted metal’s rhythm guitar, yet there’s a traditionalist streak in him, too.

As he joins us from France over a Zoom connection – a conversation you can watch in full in the video above – Duplantier acknowledges the tension between the band’s modernistic impulses and those of the old-school. But he swears that makes sense if you parse the word vintage in French and take it that it means 20 years, and thus Gojira are already vintage.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I think our roots are also in '70s and '80s rock, the beginning of progressive rock, and the beginning of electro music,” he says. “Our history is long enough that we can look back, ‘How is it we were doing it back in the day?’ Our first album was recorded on Pro Tools but we had to go through a tape. It was sort of a mix between analogue and computers.”

This tension between the forward pull of technology and our capacity for memory is something we all live with. People talk about Gen Y being digital natives, yet we were all attached to a cord at one point, we are still analogue beings, albeit “phones with legs” as Duplantier sees it.

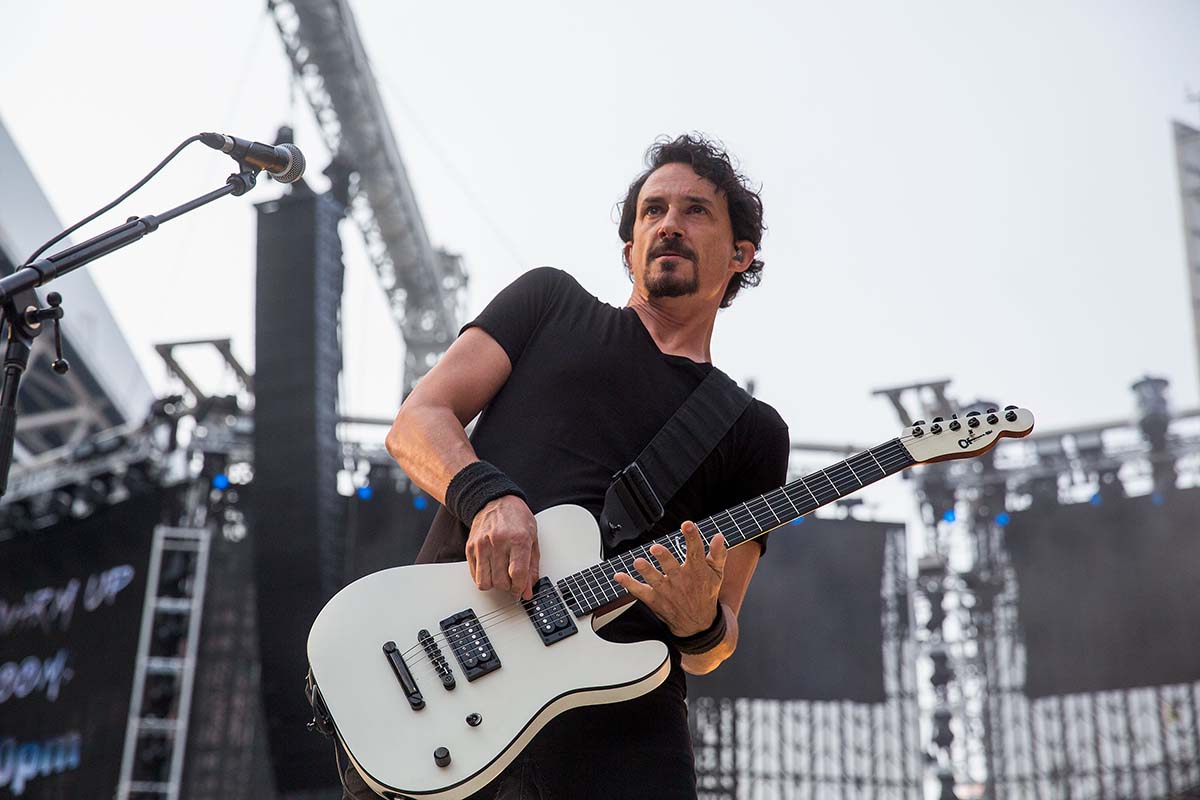

Looking at Duplantier’s rig, there’s not much between his signature Charvel and his EVH 5150 III heads. His studio rig is not unlike his live rig, which would see his guitar going into 5150 heads – both the EL34 and 6L6-equipped version – and a relatively minimalist pedal chain in his effects loop.

There's a TC Electronic Hall Of Fame Reverb, a Flashback delay and an MXR Carbon Copy delay. Going into the front of the amp there's a DigiTech Whammy, a Boss TU-3 tuner and an MXR Smart Gate Pro. You'll notice the absence of distortion or overdrives. What you hear is all from the amp.

Players in the '70s could have used as many effects as he does, but while this sense of minimalism somehow harks back to the big beasts of classic rock, it is how you use the gear. It is the thinking behind your sound rather than the tech that makes it modern.

“There is definitely something modern in what we do,” says Duplantier. “The intention, how we approach music, yeah, I would say there is something futuristic. We are trying to imagine all the solutions for a better humanity, for a better world, for a more compassionate world, and I know it sounds a bit weird.

“Maybe I am in my own mental space when I talk about that, but in my mind it is a bit futuristic. There are many traditions that we need to reinvent, many of the ways we conduct ourselves that we need to better, and to challenge, if we are to make it as a species. Therefore we are always projecting something towards the future, and towards what’s next.”

This imagining informs much of Gojira’s latest studio album, Fortitude. Produced once again by Duplantier and mixed by Andy Wallace (Sepultura / Rage Against The Machine), Fortitude is a cris de cœur, a record written and performaned in the urgent register of alarm at planetary emergencies near and far.

Tracks such as Amazonia leave little to the imagination – “The greatest miracle / Is burning to the ground” – but they are followed by action. Amazonia was launched to coincide with a fundraising campaign to support the indigenous-owned NGO The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), an initiative that has raised over $250,000 so far.

If you’ve ever caught one of Gojira's live sets, you couldn’t help but notice the physicality of the sound. Mario Duplantier’s drums resonate across the rib cage. Joe Duplantier and Christian Andreu’s guitars carpet bomb the mix with riffs, harmonic squawks and string scrapes. The frequencies and the volume creates something that’s indescribable. You have to be there.

The reality of sound travelling through the air, coming out of a big guitar amp. The sound of a drum resonating in front of you. You receive all this information in your body, and your centres, your chakras are activated!

The present planetary emergency that has us talking over Zoom rather than in person presents an interesting question. Bands have been collaborating remotely, sending in their parts to complete albums whose recording schedules were abridged by the pandemic. Could Gojira similarly function remotely? Duplantier thinks not.

“We would be missing too much,” he says. “There is a harmony created by our physical presence in a room. If I am in a room with my brother and pick up an instrument, something is going to happen. Even if we are hyper-connected with our phones and stuff. It is never the same than being in the same room.

“The reality of sound travelling through the air, coming out of a big guitar amp. The sound of a drum resonating in front of you. You receive all this information in your body, and your centres, your chakras are activated!

“When you do something you have the instant validation of your peer. When it is through a computer, through headphones, it goes only through the brain, so the other parts are missing.”

The Fortitude sessions saw Gojira switch things up in the studio. One of the biggest challenges when recording an album is being able to sustain the same enthusiasm that you had at the start of the process right through to the final moments. Ideas can get lost as the takes build up and the days go by. To counter this, Gojira committed early on in the process, putting the ideas up front and getting them on tape.

“We decided to give these characteristics that we usually do when mixing while tracking,” explains Duplantier. “We would use a certain amp, change the sound of the amp as much as possible, put on a pedal, a reverb pedal, and find that sound that we hear in our head, and once it’s there we play, just like that, and record.

“This is what we call committing to a sound, because then you can’t go back and undo what you did because it was recorded this way. We forced our vision right away onto every take, and the result was absolutely incredible. It was the first time I could press play on a track that was unmixed and get all the power and the punchiness and the shininess of a track before it is mixed.”

The above is adapted from our video interview with Joe Duplantier, which you can watch in full at the top of the page. In it he talks about the game-changing EverTune bridge, explains why he is not an effects pedal addict, unpacks Gojira's approach to manipulating volume and much more...

- Gojira's Fortitude is out now via Roadrunner.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

![Gojira - The Chant [OFFICIAL AUDIO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/xwu6gQ0JeK0/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Gojira - Born For One Thing [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/3p85-KtgDSs/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Gojira - Amazonia [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/B4CcX720DW4/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Gojira - Another World [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/iqrMFNMgVS0/maxresdefault.jpg)