Richie Hawtin on the past, present and future of techno

When Detroit techno hit our shores, few imagined that anybody could pick up the mantle and carry the torch so brightly. Nearly three decades on, Hawtin is still top of his game. We talk to a legend...

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Richie Hawtin

Manley Labs 16x2 Line Mixer

Sequentix Circlon

ROLI Seaboard RISE 25

Roland TB-3

Roland TR-8

Roland Boutique JX-03

Arturia BeatStep Pro

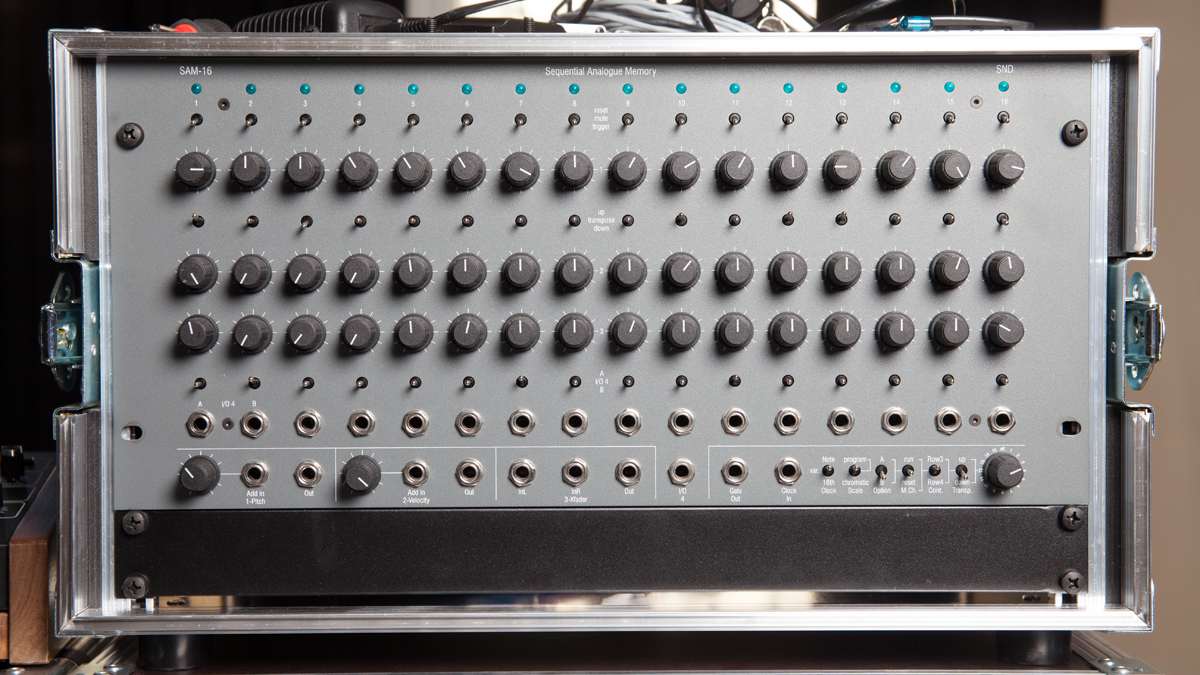

SAM-16 Sequential Analogue Memory

Dave Smith Instruments Pro-2

Sequential Prophet-6 Module

Roland System-1

Doepfer MAQ16

English-born DJ and electronic musician Richie Hawtin dropped out of university in Canada to embark on a career as a record label owner and producer in 1989. DJing just across the river from his heroes - key founders of the techno movement, Atkins, Saunderson and May - Hawtin created the Plus 8 label with John Acquaviva, which is now celebrating its 25th anniversary. Leading Detroit techno's second wave, Hawtin became a figurehead for minimal techno from the mid-'90s onwards. Best known for aliases such as Plastikman and F.U.S.E., his award-winning ENTER club night concepts draw wild acclaim across the globe.

Hawtin's love and enthusiasm for technology remains boundless. His M-nus label continues to set the standard for the techno genre, developing the careers of numerous DJs and producers. Meanwhile, he continues to actively promote techno via university lectures and production seminars. Now, with the release of a compilation of new music, From My Mind To Yours, celebrating 25 years of Plus 8, it's finally time to sit down and reflect, not just on Hawtin's past, but also on what the future has to offer.

When you started Plus 8, what were your ideals for the label and do you think you have accomplished what you set out to?

"I think we definitely accomplished what we set out to do in that very early stage, which was really about giving John Acquaviva and I a voice that could be transmitted around the world. It was the very early days of techno and we were quite excited about the music we were doing in late 1989 and 1990. I think we found ourselves in the same boat as many other people at that point. The industry wasn't that large; there were small pockets of people making music and most of them had their own labels. Derrick May had Transmat, Kevin Saunderson had KMS and Juan Atkins had Metroplex and so on, so it just felt like that was the thing to do. A very basic idea was to create our own interpretation of Detroit techno. We weren't from Detroit, but we spent so much time there and I was DJing just across the river and was so inspired by those guys."

What have been the high points, not necessarily in terms of units sold, but in the people you're worked with or seminal releases?

"Just having our first Plus 8 release out, which we did from beginning to end - it was such an exciting time. We picked the records up, went to the mastering location and got the final versions to UPS to ship off to distributors we didn't even know. We created Cybersonic with Daniel Bell, which really brought Plus 8 to the world, and that attention brought people to us, incredible people like Speedy J. Our relationship with Warp began with the Artificial Intelligence series and we had a crazy guy from Tokyo call us, which became Ken Ishii's first record. And then just hooking up with Mute Records and releasing the Plastikman series and F.U.S.E. - it just goes on and on.

"To me, the very basic thing was the excitement of it all and that this music was on the verge of tomorrow. That was what I felt and saw when I heard Derrick play, listened to his records and heard him speak. When I was around Juan and Kevin, there was this incredibly positive, futuristic momentum they were building that is still at the very heart of what I do. For me, Techno must move forward."

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Do you believe that techno has successfully adapted or mutated to reflect modern electronic music?

"That's a very good question. In a way, techno has adapted completely to the dancefloor without really following that specific 4/4 beat or having a place where it could be heard and have its own context, especially because it wasn't heard on the radio or outside of small record shops for the first 15 or 20 years. In that way, I think the rest of the world has adapted to the idea that dance music that's created for dancing can actually have a greater purpose; that it isn't just about beats but has depth and personality and storytelling, like any other great art form. So I think people have come round to respect and appreciate how far the artistry has grown and developed within techno."

Should a genre need to adapt to stay relevant or should it simply live and die by the ethos that made it viable in the first place?

"It's a mind-set, a focused direction, and the type of sub-genres or trends or fads that you're talking about that disappear are options, a certain moment in time where an idea is regurgitated and grabbed by a group of people, or the masses, and becomes or maybe overshadows the original form. But in the end, unless something really incredible comes from that new form, then everything returns to the foundation point - the original spirit. Disco was the strain that splintered into house and techno but, for me, techno embodies everything that we're trying to do; it's man versus machine, with the human character and personality being the strongest point. It's being in control of the machines that we've created ourselves, and what we've created is able to extend the power of our physicality, the power of our mind, creativity and ideas - that's what techno music is."

The music industry was a completely different landscape back then, and you also have your M-nus label, of course. What's been the most challenging aspect of running these labels?

"Digital technology and distribution has been a double-edged sword. John and I have been a part of that actual progression; we helped invest in Beatport and Final Scratch, which brought digital DJing to the masses. With that came an incredible new way to reach more people than ever before. You didn't have to have a record shop, you didn't even have to have anybody in your city that knew techno; you could just get online and find those records, and with that came a new way to monetise music.

"So we're at a point now, 25 years later, where, let's not say sales, but the penetration or the distribution and availability of all music, especially electronic music, is at an all-time high. That's absolutely incredible, but the monetisation has gone completely the opposite way, so we're sitting here, reaching more people with a scene larger than we ever imagined and actually making less money than we did then."

"The monetisation has gone completely the opposite way, so we're sitting here, reaching more people with a scene larger than we ever imagined and actually making less money than we did then."

Do you think the industry model is in any better condition now?

"I think we're coming out of it, but you used to put a 12-inch out and sell enough to pay for a label staff, the artist would make money and everyone was smiling; but now you have to think about numerous sources of income, so you're looking at publishing and streaming, limited edition white labels, CDs and digital revenues, and perhaps looking into different types of creative merchandise - not just a t-shirt, but totems or objects that relate to the music you're creating… and touring, touring, touring."

Tell us how you're personally managing the transition.

"I don't think us artists that started in the early days felt the impact as much because we made records as calling cards, which allowed us to travel the world. There was always a greater revenue source that sustained us through touring and public performance, not just royalties. That allowed us to move fluidly through that transition, but that also gets into the problem of why I didn't make much music in the past five or six years, because I was on tour. I love touring and the energy of meeting people and playing in different clubs - it's like a drug; but suddenly it was two years since I was in the studio, and it's not just about popping into the studio between gigs, because you need to have momentum."

You're about to mark the 25th anniversary of Plus 8 with the compilation From My Mind To Yours. Why did you feel this type of album would be the best way to symbolise the label?

"Music - that's where the label started in the first place. There was no bigger dream than putting out the music we were creating together and believed in by other artists. We're 35 years into this wave of electronic music that we call house and techno, so there is always some type of anniversary to celebrate every month. There's always another world tour or best of collection, and it just seemed like that wasn't the way we should go to celebrate the past."

It's fascinating the way you've done it, by recording tracks and segregating them among the different pseudonyms you've become known for. Was that tricky by design?

"The biggest challenge was carving four months out of my life to say I'm not touring and find a location that I felt comfortable in. It wasn't that I went into the studio to create this collection of music; it was more about, 'What was the essence 25 years ago?'. It was the pure pleasure of going in, writing music and having the power to release anything that you felt really excited about. There wasn't a 'F.U.S.E. day' or the need to have a particular pseudonym on this compilation. I just wanted to make music and see what happened, and over the weeks and months I started to feel, or hear, those different personalities coming out again, simply because I was giving myself time to explore and be playful.

"So I was just in the studio by myself each day with my machines - different machines. It wasn't the same studio with my old Roland TB-303 or 909 - that was of no interest to me. That wouldn't be in the spirit of Plus 8 at all; it was about creating that atmosphere and environment with the equipment that's available today to inspire myself and feel the history behind me as I'm looking forward."

Because you're so busy DJing, running a label and many other ventures, do you think that actually helps you build up stores of creative energy?

"I want this word that I can't grasp - fuck, I'm going to look in a dictionary in a minute. I knew I had to go in every day, had three months and had to be completely dedicated. I dunno how it is for everybody else, but I can tell when something's coming. Months before, I have a feeling; then I start putting the pieces in place to make that potential happen. This all started a couple of years ago. Redoing old songs and figuring out the best computer plugin stuff really got me interested in music again. Raf Simons called me up and said we have this great opportunity to play Plastikman live in Guggenheim, and I was like, 'Can I really get up and play this old show?'. So I said, 'We're not doing old shows, I'm going to make eight new visuals and eight new records', and we had to make it happen because we couldn't turn back - that became the EX album. And I didn't want to lose momentum, so at the end of last year I knew that when I landed in Berlin, if I didn't find a studio and grab that moment it would be lost and the rest of the year would just take over."

Your current studio is rented, right?

"My own studio is dismantled and locked up in a storage unit because we were in between houses. The one thing I wanted was to find a better balance between digital technology and analogue technology. For me, it's not actually so important that I get worried about how a sound is made; whether it's a new Dave Smith digital oscillator with an analogue filter or a plugin, what's important is that I can physically grab a knob or fader and twist. So I wanted to find a studio that had a big board with a lot of sends and EQs that I could limit, delay and jam out with and quickly plug in a lot of stuff, because time was of the essence.

"Some rooms really resonate with you, and somehow I had this memory of this one studio that I was looking for. I'd been in it about eight years ago for 15 minutes to see an old analogue console they had, even though I'd never recorded in that studio or any studio other than my own for 25 years."

So the desk is a Neve?

"It's got a sticker on it that says Neve, but I think it's Soundtracs - an old 70s desk. I believe it was the console that The Eurythmics used to use; not the exact one but that type of console. I didn't care what the console was - I wasn't looking for the 'Neve' sound; it was like, 'Okay, this room feels amazing and the board has 32 channels, eight sends - the minimum for me - and a parametric EQ.

"All the recordings were live jams going to the board with direct outs from each channel into a Pro Tools rig that was running all the time in the background capturing every channel at 96k. Then the album was digitally mixed in Pro Tools. So, you're partly hearing the board, the EQs and digital sources. The main thing is that I wanted to get back to jamming and recording live."

But in that setup you're also using Ableton…

"There was a computer running Ableton, although I treated that like its own little instrument controller specifically set up for a couple of Roland TB-303 plugins. If I didn't use them, I didn't touch those controllers, and if I did, I knew that I could turn to my right and that little button or knob would always control the resonance filter of the 303 plugin.

"I also surround myself with the Roland TR-8 - two of those - two of the new 303s, a Dave Smith Pro 2, a Dave Smith Prophet-12, an MAQ sequencer, Cirklon and the Engine sequencer. Beyond liking sequencers, I love machines with their own sequencers built in. The 303, 101 and Pro 1 sounded wonderful and had easy ways to sequence themselves, but 25 years later, the Roland TR-8 is a great sequencer, digitally produced with 909 and 808 sounds, which I personally absolutely love."

Are the newer versions as good as the classics?

"These days, I actually prefer using some of the Roland 303 plugins over the originals, and running them through the Urei compressor or a Tube-Tech bass EQ to give them some type of warmth or presence. I spent ten years with the old things, and they sounded great, but the new ones, like the TB-3, have something that makes them feel fresh. With the little touchscreen, you can do things that you couldn't do on the old TB-303. The Pro 2 has a little 16-step sequencer, and the MAQ and the Cirklon don't actually have sound sources, but they gave me an interesting way to control other synthesisers or even computer plugins without sitting there fiddling around in an arrangement window."

When did the mixing console come into play?

"As everything was flowing and modulating and bubbling, I would just grab onto the mixing console - just like an instrument, jam with it, press record and play. Sometimes that would be for 20 minutes or even one hour and I'd find the magic in there later. Most of what you hear on the album only has two or three edits, the F.U.S.E. track Them is one take, that's it. Once I stopped recording, maybe there were a couple of edits but it was pretty much done. I probably spent another five minutes on each track in post-production."

So more live jams than programmed tracks?

"The albums that became the basis of my whole career, DE9 - the first one - Consumed and Sheet One, were all live jams. I had to hit it and know that with a couple of edits that was all I had in post-production.

"I come from a place where all my initial recording knowledge and self-education was me in the studio by myself pressing record on a two-track reel-to-reel tape. When I finally got some money, I went to two-track DAT, but it was 1998 before I had a multi-track studio and Pro Tools. The technical innovation on this album was, yes, I had all these tracks in Pro Tools and knew that I could go back and do some post, but I didn't want to rely on that. Once you start fucking with the recording of this magical interaction of man and machine, you start to strip that away."

Because you've self-educated using hardware do you think you have a better appreciation of what gear can do?

"Well, I think there are some incredible musicians who use computers and are able to articulate themselves through them much better than I can, because I didn't grow up that way. So I don't think it's better or worse; it's what you do. If I'd have spent all those formative years sitting in front of a computer moving Lego blocks around on my screen, maybe I would have loved it.

"Let me say this, and then I'll go against myself… I want the machines and technology to capture my human interaction and, even more importantly, movements - so I need faders and knobs and want to hear that when I listen to the music. Perhaps someone else's definition of techno and electronic music is the same but their interaction is moving things around on a screen to get the perfect hi-hat offset. For some reason, Squarepusher comes to mind - it feels like he's more in the computer than I am.

"But there is some truth in what you were saying about the newer generation perhaps not having the opportunity as I did to use so much hardware. There is a cheaper entry way by getting Ableton or Cubase and all these plugins and starting to create music, and I still think it's incredible that someone can have that entry point."

But unlike them, you're actually playing the instrument?

"That's what I want. If people hear anything on From My Mind To Yours, I want them to hear me, and I want them to hear the subtleties and interplay as I'm fading things up, enjoying things and adding some delays. Of course you're hearing the Ensoniq DP/4 delay or whatever it is, but you're also hearing me bring up the frequencies. I have an absolute minimalist approach and love the beauty and interplay of very small particles of sound. It's something so subtle and beautiful, and I think you can feel that in the tracks that I chose to put on the album."

When making music, does years of playing live help - knowing what people want?

"I think it can do, but I tend not to think about clubbing or that DJ energy when I'm making music. Of course, some of my tracks, like Spastik, Substance Abuse or even Systematic on the new album, are

very tough, but I dunno. Sometimes I'm standing behind the board and mixing, dancing and moving, other times I'm sitting being hypnotised by bass and mid frequencies. If anything, I would prefer that people are hypnotised and feel like they need to close their eyes when they're listening to my music, whether it's slow or fast."

Are monitors of vital importance to you?

"You know what, monitors are incredibly important, but nobody should listen to what I'm going to say and go and buy the monitors I use. There is no one fucking right monitor - it's the room, your personality and the music you're making. The dimensions of your room are going to be key to how sound is reflecting and the sonic capabilities of that. The best thing anybody can do is go out and do a major listening session and maybe take the opportunity to take one or two things home and feel them for a day or two before spending any money. Because your friend likes Genelec doesn't mean they're going to be right for you. I did one album on Genelecs but when I hear that album now, I also hear where they stop me at a certain point. In the early days, I recorded all my original tracks on System 8s, then System 15s - huge dual concentric Tannoys.

"But to answer your question, I went to Adam and listened to their whole range because I'm setting up in a slightly different studio at the same place for early next year. So I found a pair of Adams - the Audio A8X - and I'm loving them right now. Their high-end high drivers use ribbon technology, so there's low distortion and a very clear, clean frequency response. As you can imagine, a lot of my music is like drum and bass - not the style, but the kicks and the bass with lots of little delays and snare rolls [laughs], and the Adams make all of that sound tight, but also smooth and soft at the same time."

"You know what, monitors are incredibly important, but nobody should listen to what I'm going to say and go and buy the monitors I use. There is no one fucking right monitor."

Will you be playing the new album live?

"I'll be DJing the tracks out like I would always, but over the last ten years with Plastikman, even with the EX album, it was all about creating something that sounded good but also worked in the right context and had elements that worked with visuals. Now I want to be far away from that - I just want people to have a great sonic experience. I definitely have ideas about doing a Plastikman live show, although not before 2017, and I would imagine that the beginnings of that will start to materialise in the next studio sessions."

Is playing live a domain where you're also comfortable using tried and trusted gear, or are you always on the lookout for new technologies to improvise?

"I think you said the key word there. Everything I do, at least when I feel like I'm at my best, contains some type of improvisation. In the studio, you're allowing the machines to start talking to each other, but at some point you press record and jam, and you jump on things and try things and hope to create a beautifully finished, crafted piece. On the live circuit or DJing, I've used a Push controller, Maschine and the Native Instruments' Traktor Kontrol X1, and I've recently moved back to the Allen & Heath Xone K2s. These all have different buttons and faders, which are the things that allow me to interface into the computer and other pieces of technology, express myself, and, as you say, improvise. Different mixers not only have different sounds but different ways to interact with filters or an EQ.

"I guess it's not any more complicated than a guitar player finding a guitar that feels right and maybe some foot pedals. But I definitely have ideas about where all this technology should be heading - watch this space."

How do you view electronic music today in terms of pushing the envelope?

"That's what I strive for every day I'm in the studio. Electronic music is a contemporary art form. It was an experiment 25 years ago, and people weren't sure how to experience or digest it, or even how long it would be around. But it's here, it's documented, and there are schools of electronic music around the world. But within all that we have to remember that it's a music that, at its core, wants to move somewhere new and different, wants to be a step beyond, and, as artists working within that framework, that's what we have to strive to keep fighting for."

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.